Study Guide for by John Logan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education at the Races

News GLOBE TO OPEN SAM WANAMAKER PLAYHOUSE NICHOLAS HYTNER WITH NON-SHAKESPEARE PERFORMANCES TO LEAVE NATIONAL Curriculum THEATRE IN 2015 focus with Patrice Baldwin Sir Nicholas Hytner is to step down as artistic director at the National Theatre after more than a decade at the helm. Announcing his Education at ‘the races’ departure, Hytner said: ‘It’s been a joy and a privilege to lead the At the education race course, tension is mounting. The subject horses National Theatre for ten years and I’m looking forward to the next two. that have been allowed to compete will all be running very soon. Some ‘I have the most exciting and most fulfilling job in the English- have the usual head start, some are kept lame and may not be allowed speaking theatre; and after 12 years it will be time to give someone to enter the main race at all. What happens behind the scenes in various else a turn to enjoy the company of my stupendous colleagues, who stables is already determining the subject and GCSE winners, and the together make the National what it is.’ odds are low on drama being allowed to compete fairly in the race. Hytner came to the National Theatre as the successor of Sir Trevor Drama continues to be held back. Michael Gove is apparently Nunn in 2003. He has since headed up some of the National’s most avoiding having to get an act of parliament passed, which is needed commercially successful work to date, including The History Boys, were he to change the basic structure of the current national curriculum One Man, Two Guvnors and War Horse. -

January 2012 at BFI Southbank

PRESS RELEASE November 2011 11/77 January 2012 at BFI Southbank Dickens on Screen, Woody Allen & the first London Comedy Film Festival Major Seasons: x Dickens on Screen Charles Dickens (1812-1870) is undoubtedly the greatest-ever English novelist, and as a key contribution to the worldwide celebrations of his 200th birthday – co-ordinated by Film London and The Charles Dickens Museum in partnership with the BFI – BFI Southbank will launch this comprehensive three-month survey of his works adapted for film and television x Wise Cracks: The Comedies of Woody Allen Woody Allen has also made his fair share of serious films, but since this month sees BFI Southbank celebrate the highlights of his peerless career as a writer-director of comedy films; with the inclusion of both Zelig (1983) and the Oscar-winning Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) on Extended Run 30 December - 19 January x Extended Run: L’Atalante (Dir, Jean Vigo, 1934) 20 January – 29 February Funny, heart-rending, erotic, suspenseful, exhilaratingly inventive... Jean Vigo’s only full- length feature satisfies on so many levels, it’s no surprise it’s widely regarded as one of the greatest films ever made Featured Events Highlights from our events calendar include: x LoCo presents: The London Comedy Film Festival 26 – 29 January LoCo joins forces with BFI Southbank to present the first London Comedy Film Festival, with features previews, classics, masterclasses and special guests in celebration of the genre x Plus previews of some of the best titles from the BFI London Film Festival: -

Clybourne Park Study Guide

Clybourne Park Study Guide The Theatre/Dance Department’s production oF Clybourne Park can be seen December 2 – 7 at 7:30 pm in Barnett Theatre. Tickets 262-472-2222 Monday – Friday 9:30 am – 5:00 pm The Clybourne Park Study Guide was originally created by Studio 180 Theatre, Toronto, Canada, and is being used at UW-Whitewater with Studio 180 Theatre’s permission. www.studio180theatre.com Table of Contents A. Notes for Teachers ...................................................................................................................... 3 B. Introduction to the Company and the Play .................................................................................. 4 UW-Whitewater Theatre/Dance Department .......................................................................................................... 4 Clybourne Park by Bruce Norris ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Bruce Norris – Playwright ................................................................................................................................................. 6 C. Attending the Performance ......................................................................................................... 7 D. Background Information ............................................................................................................. 8 1. Source Material: A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry ....................................................................... -

Saturday, March 14, 7:30Pm, Sunday, March 15, 3Pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30Pm & Saturday, March 21, 3Pm

Starring the future, today! Book by Music & Lyrics by JOHN CAIRD STEPHEN SCHWARTZ Based on a concept by CHARLES LISANBY Orchestrations by BRUCE COUGHLIN & MARTIN ERSKINE Saturday, March 14, 7:30pm, Sunday, March 15, 3pm, Friday, March 20, 7:30pm & Saturday, March 21, 3pm Children of Eden TMTO sponsored by Season sponsored by from CRATERIAN PERFORMANCES presents the the EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR ur story begins in the beginning, with God’s creative nature and desire to be in relationship with his children. OPerhaps you don’t believe in the Biblical narrative (with which Stephen Schwartz, as composer and storyteller, takes consider- production of able liberties), but you might have children and find “Father’s” hopes and desires for his children relatable. Or perhaps you have siblings. You certainly have parents. And so, one way or another, you’re included in this story. It’s about you. It’s about all of us. It’s about our frailties and foibles, our struggles and failures, and it’s about our curiosity, ambitions and determination to live life the way we choose. It is also, like the Bible itself, ultimately a story about hope, love and redemption. When we don’t measure up, it takes someone else’s love us to lift us up. The meaning and message in all of this is timeless, and so director Cailey McCandless cast a vision for the show that unmoors it from ancient settings. And you might notice there are very few parallel lines in the show’s design... mostly intersecting angles, because life and our relationships tend to work that way. -

RANGO (PG) Ebert: Users: You: Rate This Movie Right Now

movie reviews Reviews Great Movies Answer Man People Commentary Festivals Oscars Glossary One-Minute Reviews Letters Roger Ebert's Journal Scanners Store News Sports Business Entertainment Classifieds Columnists search RANGO (PG) Ebert: Users: You: Rate this movie right now GO Search powered by YAHOO! register You are not logged in. Log in » Subscribe to weekly newsletter » times & tickets Rango in theaters The Adjustment Bureau Fandango BY ROGER EBERT / March 2, 2011 I Will Follow Search movie Ip Man 2 showtimes and buy "Rango" is some kind of a Rango tickets. miracle: An animated Take Me Home Tonight comedy for smart cast & credits moviegoers, wonderfully more current releases » about us With the voices of: made, great to look at, one-minute movie reviews wickedly satirical, and About the site » (gasp!) filmed in glorious 2- Rango/Lars Johnny Depp D. Its brilliant colors and Beans Isla Fisher still playing Site FAQs » startling characters spring Priscilla Abigail Breslin from the screen and remind The Adjustment Bureau Contact us » Mayor Ned Beatty us how very, very tired we Roadkill Alfred Molina All Good Things are of simpleminded little Another Year Email the Movie Jake Bill Nighy characters bouncing around Barney's Version Answer Man » Doc/Merrimack Stephen Root dimly in 3-D. Biutiful Balthazar Harry Dean Stanton Blue Valentine This is an inspired comic Bad Bill Ray Winstone Casino Jack on sale now Western, deserving Cedar Rapids comparison with "Blazing Paramount Pictures presents a film Certifiably Jonathan Saddles," from which it directed by Gore Verbinski. Written The Company Men Country Strong borrows a lot of farts. -

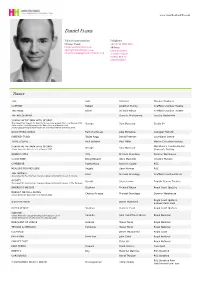

Daniel Evans

www.hamiltonhodell.co.uk Daniel Evans Talent Representation Telephone Christian Hodell +44 (0) 20 7636 1221 [email protected], Address [email protected], Hamilton Hodell, [email protected] 20 Golden Square London, W1F 9JL, United Kingdom Theatre Title Role Director Theatre/Producer COMPANY Robert Jonathan Munby Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE PRIDE Oliver Richard Wilson Sheffield Crucible Theatre THE ART OF NEWS Dominic Muldowney London Sinfonietta SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Tony Award Nomination for Best Performance by a Lead Actor in a Musical 2008 George Sam Buntrock Studio 54 Outer Critics' Circle Nomination for Best Actor in a Musical 2008 Drama League Awards Nomination for Distinguished Performance 2008 GOOD THING GOING Part of a Revue Julia McKenzie Cadogan Hall Ltd SWEENEY TODD Tobias Ragg David Freeman Southbank Centre TOTAL ECLIPSE Paul Verlaine Paul Miller Menier Chocolate Factory SUNDAY IN THE PARK WITH GEORGE Wyndham's Theatre/Menier George Sam Buntrock Olivier Award for Best Actor in a Musical 2007 Chocolate Factory GRAND HOTEL Otto Michael Grandage Donmar Warehouse CLOUD NINE Betty/Edward Anna Mackmin Crucible Theatre CYMBELINE Posthumous Dominic Cooke RSC MEASURE FOR MEASURE Angelo Sean Holmes RSC THE TEMPEST Ariel Michael Grandage Sheffield Crucible/Old Vic Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in Ghosts) GHOSTS Osvald Steve Unwin English Touring Theatre Nominated for the 2002 Ian Charleson Award (Joint with his part in The Tempest) WHERE DO WE LIVE Stephen Richard -

The Heidi Chronicles As Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States

Facultad de Humanidades Sección de Filología The Heidi Chronicles as Illustration of the Second Feminist Wave in the United States Trabajo de Fin de Grado presentado por la alumna Beatriz Sánchez Ramos bajo la supervisión de la Dra. Matilde Martín González Dpto. Filología Inglesa y Alemana Grado en Estudios Ingleses Curso 2014-15 Convocatoria de julio de 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Second Feminist Wave: A Brief Account 3. The Heidi Chronicles seen from the perspective of Second Wave Feminist Theory 4. Conclusion 5. Works Cited Abstract This final degree dissertation aims to show how vital was the Second Wave Feminism in the twentieth century in terms of women’s struggle for better conditions. This period of intense fight has been the object of many literary and critical works, such as novels, collections of poetry and scholarly articles. From the huge bibliography on this topic I have chosen to focus on The Heidi Chronicles, a play written by Wendy Wasserstein (1950-2006) which reflects and engages with the main concerns raised by women in the period covering the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. Thus, I argue that this text could very well illustrate the political, social and theoretical aspects developed within the Second Feminist Wave in the United States. A further reason for choosing this work has to do with the possibilities of theatre as a cultural manifestation to deal with questions that include gender relations and social themes. The theatre has always implied an interaction between characters in a literal way, and this turns it perhaps into the most straightforward genre to involve the public – the audience – or the readership. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D. ADDRESS Department of Sociology, UCLA 264 Haines Hall, 375 Portola Plaza, Box 951551 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551 U.S.A. Office Phone: +1 (310) 825-3532 Email: [email protected]; home page: https://soc.ucla.edu/faculty/Zhou-Min EDUCATION May 1989 Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology, State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany May 1988 Certificate of Graduate Study in Urban Policy, SUNY-Albany December 1985 Master of Arts in Sociology, SUNY-Albany January 1982 Bachelor of Arts in English, Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU), China PHD DISSERTATION The Enclave Economy and Immigrant Incorporation in New York City’s Chinatown. UMI Dissertation Information Services, 1989. Advisor: John R. Logan, SUNY-Albany • Winner of the 1989 President’s Distinguished Doctoral Dissertation Award, SUNY-Albany PROFESSIONAL CAREER Current Positions • Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA (since July 2021) • Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in U.S.-China Relations and Communications, UCLA (since 2009) • Director, UCLA Asia Pacific Center (since November 1, 2016) July 2000 to June 2021 • Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA • Founding Chair, Asian American Studies Department, UCLA (2004-2005; Chair of Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program (2001-2004) July 2013 to June 2016 • Tan Lark Sye Chair Professor of Sociology & Head of Division of Sociology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore • Director, Chinese Heritage Centre (CHC), NTU, Singapore July 1994 to June 2000 Assistant to Associate Professor with tenure, Department of Sociology & Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program, UCLA August 1990 to July 1994 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge M. -

The Influence of Bushido, Way of the Warrior, On

THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 THE INFLUENCE OF BUSHIDO ON NATHAN ALGREN’S PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT AS SEEN IN JOHN LOGAN’S MOVIE SCRIPT THE LAST SAMURAI A Thesis Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements to Obtain the Sarjana Pendidikan Degree in English Language Education By PRIMADHY WICAKSONO Student Number: 991214175 ENGLISH LANGUAGE EDUCATION STUDY PROGRAM DEPARTMENT OF LANGUAGE AND ARTS EDUCATION FACULTY OF TEACHERS TRAINING AND EDUCATION SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2007 i This thesis is dedicated to My beloved Family: ENY HARYANI and ENDHY PRIAMBODO You are the best that God has given to me iv v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank The Almighty Allah, SWT, for giving me the amazing love, courage and honor in my life. Through Allah’s love, I can stand in every moment in my life to face the sadness and happiness, and I can see that everything is beautiful. I also would like to thank my major sponsor, Drs. A. Herujiyanto, MA., Ph.D., who has devoted his time, knowledge and effort to improve this thesis. He has not only given me considerable and continual corrections, guidance, and support, but also great lessons for my life in the future. -

M. Butterfly As Total Theatre

M. Butterfly as Total Theatre Mª Isabel Seguro Gómez Universitat de Barcelona [email protected] Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly from the perspective of a semiotics on theatre, following the work of Elaine Aston and George Savona (1991). The reason for such an approach is that Hwang’s play has mostly been analysed as a critique of the interconnections between imperialism and sexism, neglecting its theatricality. My argument is that the theatrical techniques used by the playwright are also a fundamental aspect to be considered in the deconstruction of the Orient and the Other. In a 1988 interview, David Henry Hwang expressed what could be considered as his manifest on theatre whilst M. Butterfly was still being performed with great commercial success on Broadway:1 I am generally interested in ways to create total theatre, theatre which utilizes whatever the medium has to offer to create an effect—just to keep an audience interested—whether there’s dance or music or opera or comedy. All these things are very theatrical, even makeup changes and costumes—possibly because I grew up in a generation which isn’t that acquainted with theatre. For theatre to hold my interest, it needs to pull out all its stops and take advantage of everything it has— what it can do better than film and television. So it’s very important for me to exploit those elements.… (1989a: 152-53) From this perspective, I would like to analyse the theatricality of M. Butterfly as an aspect of the play to which, traditionally, not much attention has been paid to as to its content and plot. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Haworth Tompkins

Conservation Management Plan For The National Theatre Final Draft December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Conservation Management Plan for the National Theatre Final Draft - December 2008 Haworth Tompkins Ltd 19-20 Great Sutton Street London EC1V 0DR Front Cover: Haworth Tompkins Ltd 2008 Theatre Square entrance, winter - HTL 2008 Foreword When, in December 2007, Time Out magazine celebrated the National Theatre as one of the seven wonders of London, a significant moment in the rising popularity of the building had occurred. Over the decades since its opening in 1976, Denys Lasdun’s building, listed Grade II* in 1994. has come to be seen as a London landmark, and a favourite of theatre-goers. The building has served the NT company well. The innovations of its founders and architect – the ampleness of the foyers, the idea that theatre doesn’t start or finish with the rise and fall of the curtain – have been triumphantly borne out. With its Southbank neighbours to the west of Waterloo Bridge, the NT was an early inhabitant of an area that, thirty years later, has become one of the world’s major cultural quarters. The river walk from the Eye to the Design Museum now teems with life - and, as they pass the National, we do our best to encourage them in. The Travelex £10 seasons and now Sunday opening bear out the theatre’s 1976 slogan, “The New National Theatre is Yours”. Greatly helped by the Arts Council, the NT has looked after the building, with a major refurbishment in the nineties, and a yearly spend of some £2million on fabric, infrastructure and equipment.