Adolescent Suicide: the Role of the Public School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chantilly High School Chantilly, Virginia Presented By

Chantilly High School Chantilly, Virginia Presented by Chantilly High School Music Boosters We’re Glad You’re Here! e’re excited to once again host the East Coast’s premier high school jazz event and showcase the best in jazz Wentertainment. The Chantilly Invitational Jazz Festival was created 34 years ago to provide an opportunity for high school, professional jazz musicians and educators to share, learn, and compete. Over the years, bands, combos, and jazz ensembles from Virginia, Maryland, Tennessee, West Virginia and the District of Columbia have participated. Festival audiences have also heard great performances by the US Army Jazz Ambassadors, the Airmen of Note, the Jazz Consortium Big Band, Capital Bones, ensembles Workshop Jazz from nearby universities and soloists Matt Ni- ess, Tim Eyerman, Dave Detweiler, Jacques Johnson, Karen Henderson, Chris Vadala, Bruce Gates and many others. We’re delighted to welcome the Army Blues, National Jazz Orchestra, No Explanations, and the George Mason Uni- versity Jazz Band our feature ensembles. The Chantilly Invitational Jazz Festival has grown to over thirty groups battling for trophies, scholarships and most importantly, “bragging rights.” We’ve got a packed schedule for this year’s Festival. Again, welcome to the Festival — an annual March weekend which has become a tradition in the Washington area as the place to be for great jazz and special performances. Teresa Johnson, Principal Robyn Lady, Directory of Student Services, Performing Arts Supervisor Doug Maloney, Director of Bands Steve Wallace, V.P. for Bands, Chantilly Music Boosters Chris Singleton, Associate Director of Bands Betsy Watts, President, Chantilly Music Boosters Liz and Tim Lisko, Festival Coordinators Welcome We appreciate the support of all our Music Booster sponsors! We Jazz Festival Sponsors especially wish to recognize our sponsors who contributed directly to the Chantilly Jazz Festival. -

Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 265 562 CS 209 541 AUTHOR Gibbs, Sandra E., Comp. TITLE Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines, 1985. Ranked Magazines. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, PUB DATE Mar 86 NOTE 88p. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - General (130) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Awards; Creative Writing; Evaluation Criteria; Layout (Publications); Periodicals; Secondary Education; *Student Publications; Writing Evaluation IDENTIFIERS Contests; Excellence in Education; *Literary Magazines; National Council of Teachers of English ABSTRACT In keeping with efforts of the National Council of Teachers of English to promote and recognize excellence in writing in the schools, this booklet presents the rankings of winning entries in the second year of NCTE's Program to Recognize Excellence in Student Literary Magazines in American and Canadian schools, and American schools abroad. Following an introduction detailing the evaluation process and criteria, the magazines are listed by state or country, and subdivided by superior, excellent, or aboveaverage rankings. Those superior magazines which received the program's highest award in a second evaluation are also listed. Each entry includes the school address, student editor(s), faculty advisor, and cost of the magazine. (HTH) ***********************************************w*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best thatcan be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** National Council of Teachers of English 1111 Kenyon Road. Urbana. Illinois 61801 Programto Recognize Excellence " in Student LiteraryMagazines UJ 1985 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitusdocument has been reproduced as roomed from the person or organization originating it 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction Quality. -

Feeder List SY2016-17

Region 1 Elementary School Feeder By High School Pyramid SY 2016-17 Herndon High School Pyramid Aldrin ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Armstrong ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Clearview ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Dranesville ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Herndon ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Hutchison ES Herndon MS - 100% Herndon HS - 100% Herndon MS Herndon HS - 100% Langley High School Pyramid Churchill Road ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Colvin Run ES Cooper MS - 69% / Longfellow MS - 31% Langley HS - 69% / McLean HS - 31% Forestville ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Great Falls ES Cooper MS - 100% Langley HS - 100% Spring Hill ES Cooper MS - 67% / Longfellow MS - 33% Langley HS - 67% / McLean HS - 33% Cooper MS Langley HS - 100% Madison High School Pyramid Cunningham Park ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 76% / Marshall HS - 24 % Flint Hill ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 100% Louise Archer ES Thoreau MS - 100% Madison HS - 100% Marshall Road ES Thoreau MS - 63% / Jackson MS - 37% Madison HS - 63% / Oakton HS - 37% Vienna ES Thoreau MS - 97% / Kilmer MS - 3% Madison HS - 97% / Marshall HS - 3% Wolftrap ES Kilmer MS - 100% Marshall HS - 61% / Madison HS - 39% Thoreau MS Madison HS - 89% / Marshall HS - 11% Based on September 30, 2016 residing student counts. 1 Region 1 Elementary School Feeder By High School Pyramid SY 2016-17 Oakton High School Pyramid Crossfield ES Carson MS - 92% / Hughes MS - 7% / Franklin - 1% Oakton HS - 92% / South Lakes HS - 7% / Chantilly - 1% Mosby -

Costly for the Environment. Ruiyang Chen, Age 16, Shanghai World

The New York Times Learning Network 2021 Student Editorial Contest Finalists ( in alphabeticalorder by the writer's last name) Winners America Betancourt- Leon, age 16, MakingWaves Academy, Richmond, Calif.: “ Cheap for You. Costly for the Environment . Ruiyang Chen , age 16, Shanghai World Foreign Language Academy, Shanghai : “Fast & Furious 2021: Sushi's Dilemma Ju HwanKim age 17, UnitedWorld Collegeof SouthEastAsia - EastCampus, Singapore: “Why Singapore's “ Buildings Should be Conserved Lauren Koong, age 17, Mirabeau B. Lamar Senior High School, Houston , Texas: “It Took a Global Pandemic to Stop School Shootings Angela Mao, age 17 and Ariane Lee, 17, Syosset High School, Syosset, N.Y.: “ The American Teacher's Plight: Underappreciated , Underpaid and Overworked Evan Odegard Pereira, age , Nova Classical Academy, Saint Paul, Minn.: For Most Latinos, Latinx Does Not Markthe Spot Norah Rami, age 17, Clements High School, Sugar Land, Texas: “Teach Us What We Need ShivaliVora, age 17, St. Thomas Aquinas High School, Edison, N.J .: “ It's Just Hair MadisonXu, age 16, Horace MannSchool, Bronx, N.Y.: “ We Cannot Fight Anti-Asian Hate Without DismantlingAsian Stereotypes Sheerea Yu, age 15, University School of Nashville, Nashville, Tenn.: Save the Snow Day: Save TeenageEducation” Runners-Up Tala Areiqat, age 17, NorthernValley RegionalHigh Schoolat Old Tappan, Old Tappan, N.J.: How American High Schools Failed To Educate Us On Eating Disorders ” Emily Cao, age 17 Glenforest Secondary School, Mississauga, Ontario: Look on the Dark Side: The Benefits of Pessimism ” Abigail Soriano Cherith, age 17, North Hollywood High School, Los Angeles.: “ We Need More Maestrason the Podium RaquelCoren, age 18, Agnes IrwinSchool, BrynMawr, Pa.: “ The White- Washingand Appropriation Behind Trendy Spirituality Asia Foland, age 14, Wellesley Middle School, Wellesley, Mass.: “ Private Prisons: It's to Take Back the Key Jun An Guo, age 17, St. -

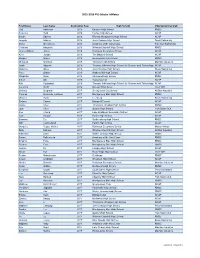

PVS Scholar Athletes

2015-2016 PVS Scholar Athletes First Name Last Name Graduation Year High School USA Swimming Club Gail Anderson 2016 Einstein High School RMSC Rebecca Byrd 2016 Fairfax High School NCAP Bouke Edskes 2016 Richard Montgomery High School NCAP Joaquin Gabriel 2016 John Champe High School Snow Swimming Grace Goetcheus 2016 Academy of the Holy Cross Tollefson Swimming Christian Haryanto 2016 Winston Churchill High School RMSC James William Jones 2016 Robinson Secondary School NCAP Kylie Jordan 2016 The Madeira School NCAP Morgan Mayer 2016 Georgetown Day School RMSC Michaela Morrison 2016 Yorktown High School Machine Aquatics Justin Nguyen 2016 Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology NCAP Madeline Oliver 2016 John Champe High School Snow Swimming Peter Orban 2016 Watkins Mill High School NCAP Margarita Ryan 2016 Sherwood High School RMSC Simon Shi 2016 Tuscarora HS NCAP Keti Vutipawat 2016 Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology NCAP Veronica Wolff 2016 McLean High Scool The FISH Zachary Bergman 2017 Georgetown Day School All Star Aquatics Thomas Brown de Colstoun 2017 Montgomery Blair High School RMSC Michael Burris 2017 Leesburg Snow Swimming Sydney Catron 2017 Bishop O'Connell NCAP Daniel Chen 2017 Thomas S. Wootton High School RMSC Jade Chen 2017 Oakton High School York Swim Club Alex Chung 2017 Lake Braddock Secondary School NCAP Cole Cooper 2017 Patriot High School NCAP Brandon Cu 2017 Gaithersburg High School RMSC Will Cumberland 2017 Patriot High School NCAP Margaret Deppe-Walker 2017 Robinson Secondary -

CHS Marching Band

tthh 2255AAnnualnn ual OOAKTONAKTON CCLASSICLASSIC AAnn InvitationalInvitational MMarchingarching BandBand CCompetitionompetition October 17, 2009 OAKTON HIGH SCHOOL Vienna, Virginia J>;CKI?9IJEH;I /PSUIFSO7"TQSFNJFSFNVTJDTUPSFGPSSFOUBMTBOEMFTTPOT LESSONS • RENTALS • SALES • REPAIRS H;IJEDCKI?9"?D9$ LESSONS 8FUFBDIPWFS TUVEFOUTFWFSZXFFL 'PY.JMM4IPQQJOH$FOUFS +PIO.JMUPO%SJWF 429!.9).3425-%.44(%34,%33/.)3!,7!93&2%% 3FTUPO 7" 7EHAVEPROFESSIONALINSTRUCTORSTOTEACH/RCHESTRAAND"AND -&)*-,#..&/ LESSONSDAYSPERWEEK+IDSANDADULTSBEGINNERTOADVANCED )PVST.POEBZѮ VSTEBZBNmQN s"AND)NSTRUMENTS s+EYBOARD s"ANJO 'SJEBZBNQN4BUVSEBZBNQN s/RCHESTRA)NSTRUMENTS s!COUSTIC'UITAR s-ANDOLIN s0ERCUSSION s%LECTRIC'UITAR s5KULELE 9>7DJ?BBOCKI?9"?D9$ s-ARIMBAS s"ASS s6OICE,ESSONS $IBOUJMMZ1BSL4IPQQJOH$FOUFS s"ELLS %-FF+BDLTPO.FN)XZ $IBOUJMMZ 7" 8FLFFQBMMJOTUSVNFOUTJOTUPDL -&)(((#./., RENTALS )PVST.POEBZѮ VSTEBZBNmQN 'SJEBZBNQN4BUVSEBZBNQN 7ERENTALL"ANDAND/RCHESTRAINSTRUMENTS $RUMS !COUSTIC AND%LECTRIC'UITARS "ASSES +EYBOARDS !MPS -ARIMBA "ANJOS JM?D8HEEA;CKI?9"?D9$ -ANDOLINSANDMUCHMORE 5XJOCSPPL$FOUSF #SBEEPDL3PBE "POFTUPQTIPQGPSBMMPGZPVSNVTJDOFFET 'BJSGBY 7" SALES -&)*(+#/+&& 7EHAVEAHUGEINVENTORYOFSHEETMUSICTITLES PLUS"ANDAND )PVST.POEBZѮ VSTEBZBNQN /RCHESTRAINSTRUMENTS $RUMS -ANDOLINS "ANJOS !COUSTICAND 'SJEBZBNQN4BUVSEBZBNQN %LECTRIC'UITARS "ASSES !MPSANDMUSICACCESSORIES BEHJEDCKI?9"?D9$ 4IPQTPG-PSUPO7BMMFZ REPAIRS "MMSFQBJSTEPOFPOTJUF 0Y3PBE -PSUPO 7" -INORTOMAJORREPAIRSONALL"ANDAND/RCHESTRA MEMBEROF .!")24 -&),/&#&&&, INSTRUMENTSINCLUDING'UITARAND"ASS )PVST.POEBZѮ -

NEWS RELEASE for Immediate Release Contact: Lizzie Archer Campaign Development Manager [email protected] 540-429-9001

NEWS RELEASE For Immediate Release Contact: Lizzie Archer Campaign Development Manager [email protected] 540-429-9001 The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s Washington D.C. Chapter Announces Local 2021 Students of the Year Winners of Whittle School and Studios and Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School — Local High School Students Relentless in Virtual Fundraising Shatter National Records for Much Needed Cancer Research & Support — Washington, D.C. 3/15/2021 – Every nine minutes, somebody in the U.S. dies of a blood cancer. And, in today’s times of uncertainty, cancer patients need support now, more than ever. Through The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society’s (LLS) Washington D.C. Chapter’s innovative fundraising campaign, Students of the Year, more than 91 motivated high school candidates broke both local and national records by raising over $3 Million in just 7 weeks through virtual fundraising for LLS’s cutting-edge cancer research and patient services. Team CUREsaders led by Calla O’Neil (Junior at Whittle School and Studios in Washington DC), Ella Song (Junior at Whittle School and Studios), and Kaeden Koons-Perdikis (Sophomore at Georgetown Visitation Preparatory School in Washington, DC), raised the most funds across the D.C. Region and earned the winning title, “Students of the Year.” These fundraising superstars raised funds to support LLS’s goal of finding cures for blood cancers and ensuring that patients have access to lifesaving treatments. Students of the Year is a seven-week philanthropic leadership development program during which students foster professional skills such as entrepreneurship, marketing, and project management in order to raise funds for LLS, a global leader in the fight against cancer. -

Mclean Redevelopment Plan Rolls Ahead Challenge Remains to Find Plan That Meets Desires but Also Can Be Implemented BRIAN TROMPETER Sta Writer

xxxx xx INSIDE: Local airports end rough year on down note • Page 2 3 16 YOUTH OFFER LANGLEY VALENTINE’S GYMNAST DAY WISHES TO VAULTS TO FRONT-LINERS STATE TITLE Sun Gazette GREAT FALLS McLEAN OAKTON TYSONS VIENNA VOLUME 42 NO. 21 FEBRUARY 25-MARCH 3, 2021 McLean Redevelopment Plan Rolls Ahead Challenge Remains to Find Plan That Meets Desires But Also Can Be Implemented BRIAN TROMPETER Sta Writer It’s experienced hiccups over the years, but the groundwork for McLean’s Com- munity Business Center (CBC) is advanc- ing. Supervisor John Foust (D-Dranes- ville), who outlined a CBC study at a Feb. 20 virtual open house, said he was im- pressed by the consensus achieved. “Like you might expect, there was not unanimous agreement, but in my experi- ence in this business, it was as close as you can get,” Foust said. “There was an amazing amount of agreement amongst those who participated on what we really need to do: Make McLean work for ev- erybody.” McLean leaders earlier pinned hopes on a “Main Street McLean” mixed-use concept that would have redeveloped ar- eas near the Giant Food shopping center. But the developer, McLean Properties, in June 2017 opted not to pursue the initia- tive. The company in 2008 also was going to submit a redevelopment plan for cen- tral McLean, but backed out because of the economic recession. Fairfax County in 2018 hired a con- sultant to hold workshops and develop a shared vision for McLean’s future, Foust said. Participants desired to set aside part of WARHAWKS WIN STATE CROWN! downtown for a more pedestrian-friendly development and agreed that protecting James Madison High School’s Alayna Arnolie drives against Osbourn Park’s Alex Harju during the Virginia High School League’s Class 6 bordering neighborhoods was a priority, girls state championship game on Feb. -

At Herndon High News, Page 16

Oak Hill ❖ Herndon ‘Express Yourself’ at Herndon High News, Page 16 Risky Behavior By the Classifieds, Page 14 Classifieds, ❖ Numbers News, Page 8 Diana Mahmoud Sports, Page 13 wears a peacock- ❖ inspired look de- signed by Barbara Kirwan during the March 14 Fashion Show at Herndon High School. Entertainment, Page 12 ❖ Opinion, Page 6 No More Food Waste At Dranesville Elementary News, Page 3 Page 10 PERMIT #86 PERMIT Martinsburg, WV Martinsburg, PAID U.S. Postage U.S. PRSRT STD PRSRT Photo by Deb Cobb/The Connection online at www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.comMarch 21-27, 2012 Oak Hill/Herndon Connection ❖ March 21-27, 2012 ❖ 1 News OPEN HOUSES SATURDAY/SUNDAY, Top Virginia Leaders to Discuss MARCH 24 & 25 Impact of Rail on Economy airfax and Reston Chamber on the F Loudoun Coun- More Information Dulles Corridor business ties have entered community’s perspective the 90-day period to de- When: March 28 on Rail to Dulles/ 11 a.m. - 11:30 a.m. Registration & Networking cide how they will fund 11:30 a.m. – 1 p.m. Lunch & Program Loudoun. Phase II of the Silver Line Where: Sheraton Reston Hotel, 11810 Sunrise Val- The full panel will in- Metrorail Project - a de- ley Drive, Reston VA 20190 clude: Tickets - to register visit http:// cision that will have a www.restonchamber.org/silverlineevent Sean T. Connaughton, major impact on local $45 for Current Chamber Members; $60 for Future Virginia Secretary of businesses. The Greater Chamber Members. Transportation; Reston Chamber of Com- Sharon Bulova, Chair- merce announced that man, Fairfax County Virginia Secretary of Transporta- discuss the latest progress and Board of Supervisors; Scott York, tion Sean T. -

Response to Questions on the FY 2018 Budget

Response to Questions on the FY 2018 Budget Request By: Supervisor Herrity Question: Please provide a list of FCPS employees who traveled for work and/or training over the last 12 months to include purpose of travel, destination, and length. Please include cost data as well. Response: The following response has been prepared by Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) in response to a similar question from School Board member Wilson. CD# TW-03 Question # 40 Page 1of 25 FY 2018 Response to Questions of the FY 2018 Budget School Board Member Requesting Information: Thomas Wilson Answer Prepared By: Kristen Michael Date Prepared: March 15, 2017 Question: Please provide a list of travel costs for all FCPS employees during the last two calendar years (FY 2016 and FY 2017 to date). Please include the employee title, employee department, date of travel, amount of travel, destination of trip, and purpose of trip. Response: Below is a summary of non-local travel cost paid by schools and departments for FY 2016 and FY 2017 through March 9, 2017. This includes travel for professional development, recruitment, and legislative travel. Following the summary chart is the detailed report that includes the employee title, employee department, date of travel, destination of trip, purpose of trip, and amount of travel cost. Department/Schools FY 2016 FY 2017 YTD Schools $ 689,555 $ 519,661 Instructional Services 178,014 96,818 Special Services 78,412 41,953 School Board Office 37,794 10,142 Facilities and Transportation 36,664 10,476 Region Office 35,626 16,628 Financial Services 31,533 27,638 Information Technology 26,899 14,849 Chief of Staff 11,919 3,916 Superintendents Office 10,044 2,172. -

2018-Fcps-Honors-Program.Pdf

RECEPTION AND RECOGNITION CEREMONY Wednesday, June 6, 2018 George Mason University Center for the Arts FCPS HONORS 1 2 FAIRFAX COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS Schedule of Events | Wednesday, June 6, 2018 Reception 6 p.m. Music Gypsy Jazz Combo West Springfield High School Keith Owens, Director Awards Ceremony 7 p.m. Opening Herndon High School Choir Dana Van Slyke, Director Welcome R Chace Ramey Recognition of the Foundation for Scott Brabrand Fairfax County Public Schools Division Superintendent Remarks on behalf of the Foundation Kevin Reynolds Regional President, Director of Sales, United Bank Chair, Foundation for Fairfax County Public Schools Employee Award Introductions R Chace Ramey Employee Award Presentations Scott Brabrand and Fairfax County School Board and Leadership Team Members Outstanding Elementary New Teacher Outstanding Secondary New Teacher Outstanding New Principal Student Performance Kishan Rao Vocalist, Herndon High School, Senior Employee Award Presentations Continue Outstanding School-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Hourly Employee Outstanding School-Based Support Employee Outstanding Nonschool-Based Support Employee Student Performance Allie Lytle Vocalist, Herndon High School, Senior Employee Award Presentations Continue Outstanding School-Based Leader Outstanding Nonschool-Based Leader Outstanding Elementary Teacher Outstanding Secondary Teacher Outstanding Principal Closing Remarks R Chace Ramey FCPS HONORS 3 The Foundation for Fairfax County Public Schools is dedicated to Signature Sponsor recognizing and celebrating the accomplishments and contributions of FCPS employees through the annual FCPS Honors event. Our Mission The Foundation for FCPS seeds strategic initiatives of FCPS that will engage and inspire students to thrive. Highest Honors Sponsor Our Initiatives State of Education Luncheon, November, 2018 Teacher Grants Program, launched May, 2018. -

Hunter Mill Road Bridge to Be Modernized VDOT Plans to Give Outdated, Single-Lane Span a $5.5 Million Makeover BRIAN TROMPETER Sta Writer

xxxx xx INSIDE: Fairfax mulls options on bamboo management • Page 7 TEXT SUNGAZETTE to 22828 14 16 to sign up SPECIAL MARSHALL SECTION LOOKS TO for weekly LOOKS DEFEND AT PETS ITS CROWN E-editions! Sun Gazette GREAT FALLS McLEAN OAKTON TYSONS VIENNA VOLUME 42 NO. 8 DECEMBER 3-9, 2020 Hunter Mill Road Bridge to Be Modernized VDOT Plans to Give Outdated, Single-Lane Span a $5.5 Million Makeover BRIAN TROMPETER Sta Writer Another decaying one-lane bridge in northeast Fairfax County is about to be replaced by a new two-lane span. The Board of Supervisors was slated Dec. 1 to endorse the Virginia Depart- ment of Transportation’s (VDOT) plans to remove a 30-foot-long, single-lane span on Hunter Mill Road at Colvin Run in the Vienna/Reston area and replace it with a 40-foot-long, two-lane bridge. The new bridge would have two 11- foot-wide travel lanes, plus safety im- provements including a rectangular, rap- id-ashing beacon, a median refuge and a splitter island to divide the approaching road lanes and encourage drivers to slow down. The ashing beacon and median ref- uge would provide additional safety for The Virginia Department of Transportation next year plans to install a new two-lane bridge on drivers, pedestrians and bicyclists where Hunter Mill Road at Colvin Run to replace this failing one-lane span, which was built in 1974. the Colvin Run Stream Valley Trail VDOT will fund most of the project, with Fairfax County chipping in the rest. crosses Hunter Mill Road just south of would need to supply $408,000 for the rosion of steel girder webs and anges, the bridge, according to a county staff splitter island, median refuge and ashing and needs immediate replacement, of- report.