DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 353 CG 021 968 TITLE Down

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Aid for the Cleveland Press Photograph Collection

Finding aid for the Cleveland Press Photograph Collection Repository: Cleveland State University Title: Cleveland Press Photograph Collection Inclusive Date(s): 1920-1982 Author: Finding aid prepared by Lynn Duchez Bycko Creation: Finding aid encoded by Kiffany Francis using the OhioLINK EAD Application in 2009 Descriptive Rules: Finding aid prepared using Finding aid prepared using Describing Archives: A Content Standard. Origination: Cole, Joseph E. Extent: 882 linear feet Physical Location: Abstract: After the Cleveland Press newspaper ceased publication on June 17, 1982. Joseph E. Cole, its publisher, donated the "morgue" to Cleveland State University. Representing the archived editorial library, sometimes referred to as a "newspaper morgue," topics focus on the news coverage of northeastern Ohio, with national and international news stories holding a secondary level of importance.The Cleveland Press photograph collection is composed of an archive of over one million photographs. Unit ID: PH2000.000PRE Language(s) of the Materials: English History of The Cleveland Press The Cleveland Press, founded by Edward W. Scripps, began as the Penny Press on 2 Nov. 1878. A small, 4-page afternoon daily, the paper continued to prosper. Shortened to the Press in 1884, and finally the Cleveland Press in 1889, by 1903 the Press was Cleveland's leading daily newspaper. As it entered the 1920s, the Press neared 200,000 in circulation. Louis B. Seltzer became the 12th editor of the Press in 1928, and under his 38-year stewardship the Press became one of the country's most influential newspapers. Seltzer readjusted its original working-class bias into a less controversial neighborhood orientation, stressing personal contacts and promoting the slogan "The Newspaper That Serves Its Readers." In the postwar period the Press continued its public service campaigns and remained an unrivaled force in Ohio politics. -

Student Handbook 2020-2021

CSU Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Student Handbook 2020-2021 CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY LEARN LAW. LIVE JUSTICE. The Student Handbook, online at https://www.law.csuohio.edu/currentstudents/resources/studenthandbook, provides vital information about the policies, programs, and requirements of Cleveland-Marshall College of Law of Cleveland State University. Every law student who matriculates at the College is responsible for knowing its contents. Cleveland-Marshall College of Law 2020-2021 Student Handbook – Table of Contents Using this Handbook ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Law School Services ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Student Services Center ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Academic Support ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Bar Exam Preparation ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Financial Aid...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Langston Apartment Project Set for Completion in August

Campus District Boundaries BRINGING OUR DISTRICT TOGETHER, ONE PAGE AT A TIME. VOLUME THREE • ISSUE FIVE VISIT US @ WWW.CAMPUSdiStrictoBS erver.com MAY 2013 THE CAMPUS INTERnational School: Langston Apartment Project set Building an Educational for Completion in August Institution from the Ground Up Demitrius Morman and Malaysia Vaughn tell what they love best about school. Langston tenant Gabe Stokes with Senior Property Manager Adam Martin. Photo by Nick Downer. Photo by Donna Dieball. By Kristina Biro By Donna Dieball dryer set. All utilities are included except for electric - cable, internet, To say that the Campus Interna- “What makes an Located at the corner of East 23rd water and trash are all free, adding to tional School (CIS) is a unique school- Street and Chester Avenue on the CSU the development’s growing appeal. The ing environment would truly be an excellent school campus, The Langston brings new Langston also has on-site management understatement. Upon entering the is the relationships energy and vitality to the Campus and offers 24-hour on-call maintenance. school, I could tell there was something District. Many see the new apart- Another major attraction to life at special about it. The building was filled within that ment complex as a catalyst for further the Langston is their Preferred Em- with music and artwork; the atmosphere school building.” investment in the neighborhood’s ployer program - CSU students receive was lively and welcoming. — Julie Beers, vibrancy and redevelopment. a waived application fee upon normal Julie Beers, principal of the CIS, was Campus International The first phase of the develop- credit approval as well as a waived $200 formerly the principal of Nobel Elemen- School's Principal ment, which included 100 apartment security deposit. -

Engagedscholarship@CSU 1995 Vol.3 No.3

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Law Notes School Publications Fall 1995 1995 Vol.3 No.3 Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/lawpublications_lawnotes How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, "1995 Vol.3 No.3" (1995). Law Notes. 46. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/lawpublications_lawnotes/46 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the School Publications at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Notes by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Volume 3 ·Issue 3 Cleveland-Marshall Law Alumni Association News N 0 T E S Dear Fellow Alumni: As the Cleveland-Marshall Law Alumni Association embarks upon its next fiscar year, I want to say that I consider. it an honor and a privilege to serve you in my capacity as President. To those who have been active members and participants in programs and projects sponsored by the Association, I thank you and trust that your suppor.t will continue. To · those of you who have not been actively involved with the association, I ·can say "with con fidence that you are missing a rich and fulfilling experience. One need only leaf through the pages of this publication to see . the degree of quali ty and level of effectiveness which have become our trademark. As the practice of law continues to change and present challenges to mew and vet eran attorneys alike, the Law Alumni Association continues to posture itself to assist its members in meeting the ever present demands of the legal pt:afession. -

The City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland

The City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland March the Thirteenth, Two Thousand and Thirteen The City Record is available online at Frank G. Jackson www.clevelandcitycouncil.org Mayor Martin J. Sweeney President of Council Containing PAGE Patricia J. Britt City Council 3 City Clerk, Clerk of Council The Calendar 3 Ward Name Board of Control 10 1 Terrell H. Pruitt Civil Service 12 2 Zachary Reed Board of Zoning Appeals 14 3 Joe Cimperman Board of Building Standards 4 Kenneth L. Johnson and Building Appeals 15 5 Phyllis E. Cleveland Public Notice 15 6 Mamie J. Mitchell Public Hearings 15 7 TJ Dow City of Cleveland Bids 15 8 Jeffrey D. Johnson Adopted Resolutions 9 Kevin Conwell and Ordinances 16 10 Eugene R. Miller Committee Meetings 20 11 Michael D. Polensek Index 20 12 Anthony Brancatelli 13 Kevin J. Kelley 14 Brian J. Cummins 15 Matthew Zone 16 Jay Westbrook 17 Dona Brady 18 Martin J. Sweeney 19 Martin J. Keane Printed on Recycled Paper DIRECTORY OF CITY OFFICIALS CITY COUNCIL – LEGISLATIVE DEPT. OF PUBLIC SAFETY – Martin Flask, Director, Room 230 President of Council – Martin J. Sweeney DIVISIONS: Dog Pound – John Baird, Chief Dog Warden, 2690 West 7th Street Ward Name Residence Correction – Robert Taskey, Commissioner, Cleveland House of Corrections, 4041 Northfield Rd. 1 Terrell H. Pruitt ..............................................16920 Throckley Avenue 44128 Emergency Medical Service – Edward Eckart, Commissioner, 1708 South Pointe Drive 2 Zachary Reed .....................................................3734 East 149th Street 44120 Fire – Paul A. Stubbs, Chief, 1645 Superior Avenue 3 Joe Cimperman .............................................................P.O. Box 91688 44101 Police – Michael C. -

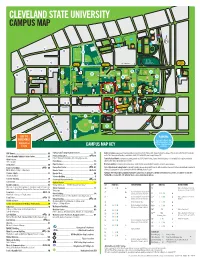

Cleveland State University Campus Map

CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS MAP 14 C.M.S.D. CLEVELAND CAMPUS SAFETY/ C.M.S.D. THE LANGSTON INTERNATIONAL POLICE STEM HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL RG WG CE DODGE COURT DODGE CG ATM & DODGE COURT BRANCH EG MB CSU ARTS CAMPUS: ART, DANCE, THEATRE 22 UG AT MG PALACE, STATE, AND 66 IDEA OHIO CAMPUS411 CENTER EASTSTREET 13TH EASTSTREET 12TH AG THEATERS ALL-IN-ONE PARKING (EASTBOUND ONLY) UN BLDG. 4 EAST 14TH STREET TC BLDG. 1 IM HURON RD. E. SWINGOS COURT 70 UNDERGRADUATE ADMISSIONS PG WELCOME CENTER BLDG. BLDG. 2 31 3 40 BOLIVAR ROAD TRANSIT CENTER EAST 14TH STREET ERIE COURT SG 41 REVISED 8/20/13 KEY TO SUMNER AVENUE PARKING BUILDINGS For current pricing and lot updates, visit Alphabetical www.csuohio.edu/ Listing CAMPUS MAP KEY parking AMC Annex ........................................................................ AA Parking and Transportation Services .............................. EC Visitors to Campus may pre-pay for parking by the hour in Lot 21, (Front of MU), Lot 22 (Student Center), Rec Garage (RG), Lot 70 (E. 24th St), Lot 66 (Julka Dr.) and Lot 54. Pay-as-you-exit parking is available in South (SG), Central (CG) and Prospect Garage (PG). Parker Hannifin Administration Center ........................... AC Physical Education.................................................. PE Robert Busbey Natatorium, Woodling Gymnasium Allen Theater ..................................................................... AT Faculty, Staff and Students may purchase parking permits via CSU GO Online Parking System. Overnight parking is not included. Cash may be accepted in Arts Campus Plant Annex ...................................................................... PA gated facilities during designated special events. Art Gallery ........................................................................ AG Plant Services .................................................................. PS Motorcycle parking is available in designated areas only. Motorcycles are prohibited from parking in vehicle spaces/garages. -

The Union Building

RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE www.KowitRealEstate.com THE UNION BUILDING 1836 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, Ohio Property Highlights Demographics: 2,000 SF of retail space fronting busy Estimated Daytime Average HH Euclid Avenue Population Employees Income 3 Miles: 79,490 3 Miles: 8,789 3 Miles: $32,600 Located in the heart of Cleveland State University’s Campus 5 Miles: 258,903 5 Miles: 14,166 5 Miles: $35,299 7 Miles: 498,004 7 Miles: 333,020 7 Miles: $43,760 The historic Union Building was built in 1913 and renovated in 2012 The Union Building consists of first floor retail and 7 floors of office Just blocks from Playhouse Square and The 9- Cleveland’s first urban resort ASHTABULA CLEVELAND SANDUSKY Contact Agents: AKRON YOUNGSTOWN NORTHEAST, OHIO NORTHEAST, Amy Doroba 216.514.1400 x124 CANTON [email protected] Kowit & Company Real Estate Group | 216.514.1400 | [email protected] | www.kowitrealestate.com The Union Building RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE 1836 Euclid Avenue AERIAL & SITE PLAN Cleveland, Ohio Krenzler Field East Fourth Street 17,229 Students 820,000 in Attendance (2011) 1.8 Million in Attendance (2011) PROPERTY AERIAL PROPERTY SITE PLANSITE Contact Agents: 6009-B Landerhaven Drive, Suite B Amy Doroba Mayfield Heights, Ohio 44124 216.514.1400 x124 P: 216.514.1400 | www.kowitrealestate.com [email protected] The Union Building RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE 1836 Euclid Avenue CSU CAMPUS MAP Cleveland, Ohio CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS MAP THE LANGSTON RG WG CE DODGE COURT DODGE CG ATM & DODGE COURT BRANCH EG MB CSU ARTS CAMPUS: ART, DANCE, THEATRE 22 UG AT MG PALACE, STATE, AND 66 IDEA OHIO 21 CAMPUS411 CENTER EASTSTREET 13TH EASTSTREET 12TH AG THEATERS ALL-IN-ONE (EASTBOUND ONLY) UN BLDG. -

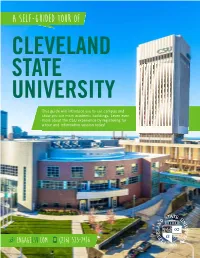

Cleveland State University a Self-Guided Tour Of

A SELF-GUIDED TOUR OF CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY This guide will introduce you to our campus and show you our main academic buildings. Learn even more about the CSU experience by registering for a tour and information session today! ENGAGECSU.COM (216) 523-7416 Schedule a guided campus tour at engagecsu.com/visit! elcome to Cleveland State University, the home of engaged learning! Established in 1964 as a small state university, Cleveland State University has grown into a vibrant urban campus in the heart of downtown. With over 175 academic programs and several thousand GUIDED internships offered every year, there are many ways for students to get involved in their major, both on campus and in their field of study. Tour Students at Cleveland State University have the opportunity to work and Hours learn alongside industry professionals in every program, whether they are M,W,F Grammy Award winning musicians, Cleveland Clinic health professionals, or 10 a.m. Fulbright Scholars. Our internship and co-op programs get students out of the & 2 p.m. classroom and into the field, giving them the chance to learn by experience. T,TH 10 a.m. Our campus is within walking distance of Playhouse Square, Progressive Field, Quicken Loans Arena, East Fourth Street, and many more exciting destinations. SAT 1st and 3rd of CSU students enjoy many benefits, including small class sizes (with an every month, average class size of 23 students), an RTA pass for public transit, a student 10 a.m.* ticket program for local entertainment, and free entry to university sporting events. -

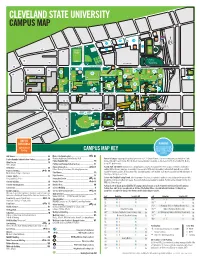

Cleveland State University Campus Map

CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS MAP THE LANGSTON WG RG CG CE DODGE COURT DODGE ATM & DODGE COURT BRANCH EG MB CSU ARTS CAMPUS: ART, DANCE, THEATRE 22 UG AT MG PALACE, STATE, AND 66 IDEA OHIO 21 CAMPUS411 CENTER THEATERS EAST STREET 13TH EAST STREET 12TH AG ALL-IN-ONE (EASTBOUND ONLY) UN BLDG. 4 EAST 14TH STREET BLDG. 1 HURON RD. E. SWINGOS COURT FUTURE HOME OF UNDERGRADUATE ADMISSIONS CENTER FOR PG INNOVATION IN HEALTH PROFESSIONS WELCOME CENTER BLDG. BLDG. 2 3 40 BOLIVAR ROAD TRANSIT CENTER EAST 14TH STREET ERIE COURT SG 80 REVISED 8/20/13 SUMNER AVENUE KEY TO BUILDINGS PARKING For current pricing Alphabetical and lot updates, visit Listing CAMPUS MAP KEY www.csuohio.edu/ parking AMC Annex ........................................................................ AA Music & Communication ..................................... MU Parker Hannifin Administration Center ........................... AC Waetjen Auditorium, Drinko Recital Hall Visitors to Campus may pre-pay for parking by the hour in Lot 22 (Student Center). Pay-as-you-exit parking is available in South Parker Hannifin Hall ......................................................... PH Garage (SG) and Prospect Garage (PG). Short-term metered parking is available on city streets, E. 24th Street and Lot 66. Meters Allen Theater ..................................................................... AT accept U.S. quarters only. Arts Campus Parking and Transportation Services .............................. EC Art Gallery ....................................................................... -

2018 Cleveland Cardio Conference Brochure

The Alliance of Cardiovascular Professionals (ACVP) represents more than 3,000 professionals serving in all areas of cardiovascular care. ACVP’s strength lies in the fact that we have combined all of the cv specialties and disciplines. This diversity provides a rich resource for learning, networking, and a strong voice in the field. ACVP is a unique catalyst for advancement. Informa- tion and learning takes a leap forward with ACVP. ACHIEVEMENT CLEVELAND ABOUT CARDIO CONFERENCES With all of the pressures facing cardiovascular profes- CARDIO sionals today, there has never been a more important time to come together to learn, network, and support CONFERENCE each other to make advancements in your own career CONNECTION and supporting patients. April 14, 2018 The Alliance of Cardiovascular Professionals brings you regional meetings to provide you with information, net- Saturday working and support. Sponsored by the Alliance of Cardiovascular Professionals and Membership is open to all professionals working in the cardiovascular arena. Benefits of member- ship include publications, 200+ continuing edu- VALUE cation hours available including online access to free CEs, networking, recognition, representation PASSION and more. CONFERENCES FOR YOU If you are a leader, if you want to be a leader, If you are a nurse, technologist, RT, Manager, Adminis- if you are committed to your career or you just trator or work anywhere in cardiovascular services, this want to stay ahead of the curve, join ACVP today! program is for you! www.acp-online.org PO -

County, MMPI Grew Apart Bruce Carroll — Right, of Last Wednesday, Sept

20130923-NEWS--1-NAT-CCI-CL_-- 9/20/2013 3:53 PM Page 1 $2.00/SEPTEMBER 23 - 29, 2013 ANALYSIS INSIDE Sizing up the competition County, MMPI grew apart Bruce Carroll — right, of Last Wednesday, Sept. 18, Cuya- Schoolbelles Coming split of tradeshow partners reflects divergent paths hoga County Executive Ed FitzGer- — and other ald told Crain’s his administration By JAY MILLER smaller ter for Health Innovation with what MMPI Inc. of Chicago, are parting, and MMPI are looking for an expe- [email protected] Northeast Ohio can happen when two people marry it appears, because neither side has rienced convention center manag- too young, before each really knows maintained the enthusiasm for the retailers are er to take over operations at the seeing their school uniform It isn’t hard to compare the part- where their lives are headed. other that they had when they were complex. business facing more of a ing of the ways at the Cleveland Cuyahoga County and its part- courting a half-dozen years ago and challenge from major companies Convention Center and Global Cen- ner, tradeshow complex manager then got hitched in 2010. See MMPI Page 18 such as Walmart, Target, Kmart and TJ Maxx. PAGE 3 OHIO CITY Third HOME TO Frontier MARKET may open OPTIMISM its wallet Area has experienced an ‘enormous’ change in sales As venture funds of houses at $200K and up struggle to raise cash, commission By STAN BULLARD [email protected] ponders investing atty and Steve Roberts recently sold their By CHUCK SODER four-bedroom, Shaker Heights home with [email protected] a large yard and in-ground pool to down- size, because their daughters are grown. -

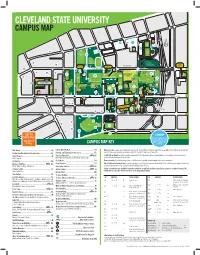

Cleveland State University Campus Map

CLEVELAND STATE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS MAP 14 TD C.M.S.D. CLEVELAND CAMPUS SAFETY/ C.M.S.D. THE LANGSTON INTERNATIONAL POLICE STEM HIGH SCHOOL SCHOOL CONSTRUCTION ZONE RG WG NEW ENGINEERING CE DODGE COURT DODGE CG BUILDING ATM & DODGE COURT BRANCH EG MB CSU ARTS CAMPUS: ART, DANCE, THEATRE 22 UG AT MG PALACE, STATE, TC AND 66 IDEA OHIO CAMPUS411 CENTER 21 EASTSTREET 13TH EASTSTREET 12TH AG THEATERS ALL-IN-ONE PARKING (EASTBOUND ONLY) UN BLDG. 4 EAST 14TH STREET BLDG. 1 IM HURON RD. E. SWINGOS COURT 70 UNDERGRADUATE43 ADMISSIONS P PG WELCOME CENTER BLDG. BLDG. 2 31 3 40 BOLIVAR ROAD TRANSIT CENTER EAST 14TH STREET ERIE COURT SG 41 REVISED 8/20/13 43 KEY TO SUMNER AVENUE PARKING BUILDINGS For current pricing and lot updates, visit Alphabetical www.csuohio.edu/ Listing CAMPUS MAP KEY parking AMC Annex ........................................................................ AA Parker Hannifin Hall ......................................................... PH Visitors to Campus may pre-pay for parking by the hour in Lot 21, (Front of MU), Lot 22 (Student Center), Rec Garage (RG), Lot 70 (E. 24th St), Lot 66 (Julka Dr.) and Lot 54. Pay-as-you-exit parking is available in South (SG), Central (CG) and Prospect Garage (PG). Parker Hannifin Administration Center ........................... AC Parking and Transportation Services .............................. EC Allen Theater ..................................................................... AT Physical Education.................................................. PE Faculty, Staff and Students may purchase parking permits via CSU GO Online Parking System. Overnight parking is not included. Cash may be accepted in Arts Campus Robert Busbey Natatorium, Woodling Gymnasium gated facilities during designated special events. Art Gallery ........................................................................ AG Plant Annex ...................................................................... PA Motorcycle parking is available in designated areas only.