The Business of Death in Chinatown

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature

Lublin Studies in Modern Languages and Literature VOL. 43 No 4 (2019) FACULTY OF HUMANITIES MARIA CURIE-SKŁODOWSKA UNIVERSITY LUBLIN STUDIES IN MODERN LANGUAGES AND LITERATURE UMCS 43(4)2019 http://journals.umcs.pl/lsml ii e-ISSN:.2450-4580. Publisher:.. Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University.. Lublin,.Poland. Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University.Press. MCSU.Library.building,.3rd.floor. ul ..Idziego.Radziszewskiego.11,.20-031.Lublin,.Poland. phone:.(081).537.53.04. e-mail:.sekretariat@wydawnictwo .umcs .lublin .pl www .wydawnictwo .umcs .lublin .pl Editorial Board Editor-in-Chief Jolanta Knieja,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Deputy Editors-in-Chief Jarosław Krajka,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Anna Maziarczyk,.Maria.Curie-Skłodowska.University,.Lublin,.Poland Statistical Editor Tomasz Krajka,.Lublin.University.of.Technology,.Poland. International Advisory Board Anikó Ádám,.Pázmány.Péter.Catholic.University,.Hungary. Monika Adamczyk-Garbowska,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Ruba Fahmi Bataineh,.Yarmouk.University,.Jordan. Alejandro Curado,.University.of.Extramadura,.Spain. Saadiyah Darus,.National.University.of.Malaysia,.Malaysia. Janusz Golec,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Margot Heinemann,.Leipzig.University,.Germany. Christophe Ippolito,.Georgia.Institute.of.Technology,.United.States.of.America. Vita Kalnberzina,.University.of.Riga,.Latvia. Henryk Kardela,.Maria.Curie-Sklodowska.University,.Poland. Ferit Kilickaya,.Mehmet.Akif.Ersoy.University,.Turkey. Laure Lévêque,.University.of.Toulon,.France. Heinz-Helmut Lüger,.University.of.Koblenz-Landau,.Germany. Peter Schnyder,.University.of.Upper.Alsace,.France. Alain Vuillemin,.Artois.University,.France. v Indexing Peer Review Process 1 . Each.article.is.reviewed.by.two.independent.reviewers.not.affiliated.to.the.place.of. work.of.the.author.of.the.article.or.the.publisher . 2 . -

Download Map and Guide

Bukit Pasoh Telok Ayer Kreta Ayer CHINATOWN A Walking Guide Travel through 14 amazing stops to experience the best of Chinatown in 6 hours. A quick introduction to the neighbourhoods Kreta Ayer Kreta Ayer means “water cart” in Malay. It refers to ox-drawn carts that brought water to the district in the 19th and 20th centuries. The water was drawn from wells at Ann Siang Hill. Back in those days, this area was known for its clusters of teahouses and opera theatres, and the infamous brothels, gambling houses and opium dens that lined the streets. Much of its sordid history has been cleaned up. However, remnants of its vibrant past are still present – especially during festive periods like the Lunar New Year and the Mid-Autumn celebrations. Telok Ayer Meaning “bay water” in Malay, Telok Ayer was at the shoreline where early immigrants disembarked from their long voyages. Designated a Chinese district by Stamford Raffles in 1822, this is the oldest neighbourhood in Chinatown. Covering Ann Siang and Club Street, this richly diverse area is packed with trendy bars and hipster cafés housed in beautifully conserved shophouses. Bukit Pasoh Located on a hill, Bukit Pasoh is lined with award-winning restaurants, boutique hotels, and conserved art deco shophouses. Once upon a time, earthen pots were produced here. Hence, its name – pasoh, which means pot in Malay. The most vibrant street in this area is Keong Saik Road – a former red-light district where gangs and vice once thrived. Today, it’s a hip enclave for stylish hotels, cool bars and great food. -

MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE HALAL DINING•PRAYERHALAL SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES to Singapore Your FOREWORD

Your MUSLIM VISITOR GUIDE to Singapore HALAL DINING • PRAYER SPACES • CULTURE • STORIES FIRST EDITION | 2020 | ENGLISH VERSION EDITION | 2020 FIRST FOREWORD Muslim-friendly Singapore P18 LITTLE INDIA Muslims make up 14 percent of Singapore’s population As a Muslim traveller, this guide provides you and it is no surprise that this island state offers a large with the information you need to enjoy your stay variety of Muslim-friendly gastronomic experiences. in Singapore — a city where your passions in life MASJID SULTAN P10 KAMPONG GLAM Many of these have been Halal certified by MUIS, are made possible. You may also download the P06 ORCHARD ROAD also known as the Islamic Religious Council of MuslimSG app and follow @halalSG on Twitter for Singapore (Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura). Visitors any Halal related queries while in Singapore. can also consider Muslim-owned food establishments throughout the city. Furthermore, mosques and – Majlis Ugama Islam Singapura (MUIS) musollahs around the island allow you to fulfill your P34 ESPLANADE religious obligations while you are on vacation. TIONG BAHRU P22 TIONGMARKET BAHRU P26 CHINATOWN P34 MARINA BAY CONTENTS 05 TIPS 26 CHINATOWN ORCHARD 06 ROAD 30 SENTOSA KAMPONG MARINA BAY & MAP OF SEVEN 10 GLAM 34 ESPLANADE NEIGHBOURHOODS This Muslim-friendly guide to the seven main LITTLE TRAVEL P30 SENTOSA neighbourhoods around 18 INDIA 38 ITINERARIES Singapore helps you make the best of your stay. TIONG HALAL RESTAURANT 22 BAHRU 42 DIRECTORY Tourism Court This guide was developed with inputs from writers Nur Safiah 1 Orchard Spring Lane Alias and Suffian Hakim, as well as CrescentRating, a leading Singapore 247729 authority on Halal travel. -

Government Agencies to Conduct Trials on Digital Payment of Parking Charges

PRESS RELEASE Government Agencies to Conduct Trials on digital payment of parking charges In line with our vision to become a Smart Nation, the Government is developing a digital parking mobile application to allow motorists to pay parking charges through their mobile devices. 2 The Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and Housing & Development Board (HDB), in partnership with the Government Technology Agency of Singapore (GovTech), are developing a mobile application for motorists to use at public car parks that currently use paper coupons. 3 The mobile app will provide more convenience for motorists as they need not return to their vehicles to add more coupons to extend their parking session. The benefits of the app include: ● Paying for parking digitally: Motorists can use the app to key in their vehicle number, select the car park, indicate their parking duration and start parking. ● Calculating parking charges automatically: The app automatically calculates the charges that motorists have to pay based on their parking duration on a per minute basis. A refund will be given if motorists choose to end their parking session earlier. ● Extending parking session remotely: The app allows motorists to track the validity of their parking session. They can extend the duration of their parking session at their own time and convenience. 4 A trial will be conducted among public sector officers from May to June 2017 to test the functionalities of the app at selected public car parks in the city area. During this period, we will test the app, especially the payment module, to be confident of its robustness before we extend the trial to the general public. -

Annex a – List of Participating Car Parks Participating

Annex A – List of participating car parks Participating URA car parks No. Car park name 1 AMOY STREET 2 ANN SIANG ROAD 3 ARMENIAN ST / CANNING RISE OFF STREET 4 ARMENIAN STREET 5 BANDA STREET 6 BANDA STREET / SAGO LANE OFF STREET 7 BERNAM STREET 8 BOON TAT STREET 9 BUKIT PASOH ROAD 10 CANNING RISE OFF STREET (MCYS-LAND) 11 CARPENTER STREET 12 CHENG YAN PLACE 13 CIRCULAR ROAD 14 CLEMENCEAU AVE 15 CLUB STREET 16 CLUB STREET OFF STREET 17 COOK STREET 18 DUXTON ROAD 19 EMERALD HILL ROAD 20 EMERALD LINK 21 ENGGOR STREET 22 FORT CANNING PARK A OFF STREET (NPARKS) 23 FORT CANNING PARK B OFF STREET (NPARKS) 24 FORT CANNING PARK C OFF STREET (NPARKS) 25 GEMMILL LANE 26 HONG KONG STREET 27 HULLET ROAD 28 JIAK CHUAN ROAD 29 KEONG SAIK ROAD 30 LIANG SEAH STREET 31 LORONG TELOK 32 MANILA STREET 33 MCCALLUM STREET 34 MIDDLE ROAD OFF STREET 35 MND SURFACE CARPARK 36 MOSQUE STREET 37 MT EMILY ROAD 38 NEIL ROAD 39 NEW MARKET ROAD 40 NIVEN ROAD 41 NORTH CANAL ROAD 42 PALMER ROAD 43 PECK SEAH STREET 44 PENANG LANE 45 PHILLIP STREET 46 PRINSEP STREET (MIDDLE ROAD / ROCHOR CANAL) 47 PURVIS STREET 48 QUEEN STREET 49 RAFFLES BOULEVARD COACH PARK 50 SAUNDERS ROAD 51 SEAH STREET 52 SERVICE ROAD BET LIANG SEAH STREET / MIDDLE ROAD 53 SERVICE ROAD OFF QUEEN ST(QUEEN / WATERLOO ST) 54 SHORT STREET 55 SOPHIA ROAD 56 STANLEY STREET 57 TAN QUEE LAN STREET 58 TANJONG PAGAR ROAD 59 TECK LIM ROAD 60 TELOK AYER STREET 61 TEMPLE STREET 62 TEO HONG ROAD 63 TEO HONG ROAD/ NEW BRIDGE ROAD OFF STREET 64 TRAS STREET 65 UPPER CIRCULAR ROAD 66 UPPER HOKKIEN STREET 67 WALLICH STREET 68 WATERLOO STREET 69 WILKIE ROAD 70 YAN KIT ROAD Participating HDB car parks No. -

Singapore Base Map A1 Map with Bus Service 120216

SAM at 8Q Coleman Street Havelock Road 130 133 Masonic Armenian B 145 197 Havelock Sq Havelock New Market Road Hall Church of Saint 2 12 32 33 51 Clarke Gregory the 61 63 80 197 851 960 Illuminator B B Former Central Fire Station/ Hill Street Thong Quay Civil Defence 2 12 33 Chai Fort Canning Heritage Museum Bras Basah Road Stamford Road 147 190 Medical Park Institution Old Hill Street B Eu Tong Sen Street Coleman Police Station Bridge 124 145 147 Clarke Quay B 2 12 33 Carver Street New Bridge Road 166 174 190 147 190 7 14 16 36 77 Chinatown Eu Tong Sen Street 851 106 111 131 162M Coleman Street 167 171 175 B Kreta Ayer Road Ayer Kreta New Bridge Road Temple Street 700A 850E 857 CHIJMES 951E 971E North Boat Quay B 2 12 33 HighStreet The Upper Circular Road Circular Upper Capitol Keong Saik Road North Canal Road 147 190 Upper Cross Street Carpenter Street Upper Hokien Street Hongkong Street Hong Lim Park 32 195 B Mosque Street Pagoda Street 51 61 63 80 124 North Bridge Road 145 166 174 197 B Elgin 851 961 961C B Bridge 61 124 Trengganu Street 32 51 63 145 166 14 16 36 77 106 111 Temple Street B 80 195 851 197 130 131 133 162M 167 Smith Street 961 961C Raes City 171 502 518 700A Sago Street Chinatown The Adelphi City Hall Tower 850E 857 951E 960 Supreme Saint Andrew’s South Bridge Road Place Parliament Court Cathedral B Banda St Building Raes Hotel Masjid Jamae (Chulia) Supreme Court Lane Sri Road Starting Buddha Tooth Mariamman Pickering Street North Canal Road Point Relic Temple & Temple South Canal Road Museum Parliament 56 57 100 107M -

Chinatown's Shophouses

Chinatown Stories | Updated as of June 2019 Chinatown’s Shophouses As architectural icons reflecting Singapore’s multi-cultural influences, Chinatown’s shophouses exude timeless appeal. Chinatown’s shophouses are among its top architectural gems. The earliest shophouses in Singapore were built in the 1840s along South Bridge Road and New Bridge Road. In the century to come, these iconic buildings sprang up on almost every street of Chinatown, including Keong Saik Road, Kreta Ayer Road, Mosque Street, Pagoda Street, Smith Street, Sago Street, Temple Street, Trengganu Street, Upper Chin Chew Street, Upper Hokkien Street, Upper Nankin Street and Upper Cross Street. An important part of Singapore’s colonial heritage, they served the commercial and residential needs of the waves of Chinese immigrants who made Singapore their home. A typical shophouse is a two- or three-storey terraced unit with a commercial shop on the ground floor, and living quarters on the second and third floors. Besides residential and commercial use, they have, at various times, also functioned as government administrative offices, public clinics, schools, hotels, places of worship, cinemas and theatres. Singapore’s oldest girls’ school, St Margaret’s, first operated from a shophouse in North Bridge Road in 1842. The first Anglo-Chinese School also conducted its first class in a shophouse at 70 Amoy Street in 1886 for 13 children of Chinese merchants. Archetypical design Most shophouses feature pitched roofs, internal air wells to allow light and air into dark and narrow interiors, rear courts and open stairwells. They are joined via common party walls and five-foot-ways (sheltered walkways). -

Place-Remaking Under Property Rights Regimes: a Case Study of Niucheshui, Singapore

Working Paper 2006-05 Place-Remaking under Property Rights Regimes: A Case Study of Niucheshui, Singapore Jieming Zhu, Loo-Lee Sim, and Xuan Liu Department of Real Estate National University of Singapore Institute of Urban and Regional Development University of California at Berkeley 2 Table of Contents Abstract........................................................................................................5 I. Introduction.........................................................................................7 II. Property Rights and Place-Making: Theoretical Discussion ..............9 III. Development of Niucheshui by the 1950s........................................13 IV. Redevelopment of Niucheshui 1960–2000.......................................15 V. Property Rights Regime over the Land Redevelopment Market of Niucheshui ........................................................................................21 VI. Place-Remaking under the State-Dominated Property Rights Regime ..............................................................................................26 VII. Conclusion ........................................................................................29 References..................................................................................................31 3 List of Figures Figure 1: Jackson Plan (1823) ...................................................................8 Figure 2: Niucheshui in the 1950s...........................................................14 Figure 3: Niucheshui in 2000 -

The Straits Chinese Contribution to Malaysian Literary Heritage: Focus On

Journal of Educational Media & Library Sciences, 42 : 2 (December 2004) :179-198 179 The Straits Chinese Contribution to Malaysian Literary Heritage: Focus on Chinese Stories Translated into Baba Malay S.K. Yoong Faculty University Tunku Abdul Rahman Library E-mail: [email protected] A.N. Zainab Faculty Computer Science & Information Technology, University of Malaya Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The Chinese born in the Straits Settlements of Peninsula Malaya (Penang, Singapore, Malacca) are called Babas to distinguish them from those born in China. The Babas are rooted from three different races, Chinese, Malay and English and as such their lifestyles show a mixed blend of the Chinese, Malay and European cultures. Because of this cultural background, the Babas exhibited a unique cultural mix in the clothes they wear, their culinary skills, architectural styles, language and literature. The paper describes the characteristics of 68 Baba translated works published between 1889 and 1950; focusing on the publi- cation trends between the period under study, the persons involved in the creative output, the publishers and printers involved, the contents of the translated works, the physical make-up of the works and the libraries where these works are held. Keywords: Baba Peranakan literature; Chinese in Malaya; Malacca; Singapore; Publishing and publishers; Printing presses; Authorship pattern The Chinese Babas The Chinese born in the Straits Settlements of Peninsula Malaya (Penang, Singapore, Malacca) are called Babas to distinguish them from those born in China (Tan, 1993). Today, the Babas refer to the descendents of the Straits born Chinese. The female Straits born Chinese are referred to as Nyonyas. -

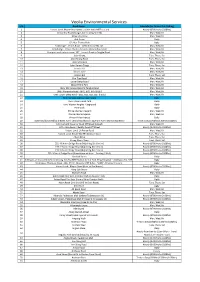

Veolia Environmental Services

Veolia Environmental Services S/N Road Name Schedule (Inc Drain Litter Picking) 1 Vacant Land: Mayne Road (next to Little India MRT station) Hourly (0700hrs to 0100hrs) 2 Alexandra Road (Ganges Ave to Leng Kee Rd) Mon, Wed, Fri 3 Alexandra View Mon, Wed, Fri 4 Ash Grove Daily 5 CP: Mar Thoma Park Daily 6 Footbridge - Jervois Road behind house No. 40 Mon, Wed, Fri 7 Footbridge - Prince Charles Crescent (Alexandra canal) Mon, Wed, Fri 8 Footpath and staircase near 107 Jervois Road to Tanglin Road Mon, Wed, Fri 9 Jalan Kilang Tues, Thurs, Sat 10 Jalan Kilang Barat Tues, Thurs, Sat 11 Jalan Membina Mon, Wed, Fri 12 Jalan Rumah Tinggi Tues, Thurs, Sat 13 Jervois Hill Mon, Wed, Fri 14 Jervois Lane Mon, Wed, Fri 15 Keppel Hill Tues, Thurs, Sat 16 Kim Tian Road Mon, Wed, Fri 17 Lower Delta Road Mon, Wed, Fri 18 Mount Echo Park Mon, Wed, Fri 19 Near 107 Jervois Road to Tanglin Road Mon, Wed, Fri 20 OHB: Alexandra Road - (B01, B03, B05 & B07) Mon, Wed, Fri 21 OHB: Lower Delta Road - (B01, B03, B05, B07 & B10) Mon, Wed, Fri 22 Park: Ganges Avenue Open Space Daily 23 Park: Kheam Hock Park Daily 24 Park: Watten Heights Playground Daily 25 Pine Walk Daily 26 Prince Charles Crescent Mon, Wed, Fri 27 Prince Charles Square Mon, Wed, Fri 28 Prince Philip Avenue Daily 29 State land bounded by sheares Ave / Central Boulevard / Bayfront Ave / Marina Boulevard Thrice a day (0700hrs/1100hrs/1500hrs) 30 URA Carpark: Spooner Road Off Street Carpark Mon, Wed, Fri 31 URA: Jalan Besar / Beatty Road Off Street Hourly (0700hrs to 0100hrs) 32 Vacant Land: 1A Peirce -

Central South Drain Schedule

Integrated Public Cleaning Central South Subject: Drain Schedule Dear residents, Below is the summary of drain types within Central South region maintained by Sembcorp: INTEGRATED PUBLIC CLEANING CENTRAL SOUTH – DRAINS Submerged Outlet Drains Non- Submerged Outlet Drains Anti-Malaria (AM)/ Earth Drains Conduit Drains Open Roadside Drains Closed Roadside Drains You may click on the above link for each drain type or refer to the full list on these subsequent pages. If you have any enquires on our cleaning schedules, please feel free to contact us at our hotline 1800 898 1920 or email us at [email protected]. Page 1 of 49 Integrated Public Cleaning Central South Subject: Submerged Outlet Drain Cleaning Schedule Dear residents, The submerged outlet drains within Central South region will be cleaned as per the schedule below: Flotsam S/N Submerged Outlet Drain Schedule 1 15m wide Bukit Timah Canal from the outlet of the culvert across Newton Daily circus at Kampong Java Road/Keng Lee Road and running between them to the outlet of the culvert across Thomson Road including all the culverts across Kampong Java Road and Keng Lee Road within the stretch of the canal. 2 15m wide Bukit Timah Canal from the outlet of the culvert across Thomson Daily Road running between Kampong Java Road and Keng Lee Road to the outlet of the culvert across Bukit Timah Road opposite Mackenzie Road including all the culverts across Kampong Java Road and Keng Lee Road within the stretch of the canal. 3 14m wide open Bukit Timah Canal between Lamp -

New Merchant (May-Jun 2021) Amex Offer

NEW MERCHANT (MAY-JUN 2021) AMEX OFFER Participating merchant listing MERCHANT NAME ADDRESS POSTAL CODE @3 63 KAMPONG BAHRU ROAD #01-01 169369 7 WONDERS SEAFOOD 369 JALAN BESAR 208997 AMEISING 16 RAFFLES QUAY #01-02A HONG LEONG BUILDING 048581 ANTEA SOCIAL 9 TYRWHITT ROAD 207528 ARIS STUDIO 23 18 LORONG MAMBONG -- HOLLAND VILLAGE CENTER 277678 BENG WHO COOKS 39 NEIL ROAD #01-39 088823 BEYOND PANCAKES 180 KITCHNER ROAD #02-35/36 CITY SQUARE MALL 208539 6 RAFFLES BOULEVARD #03-131A MARINA SQAURE O39594 BURGER FRITES 340 JOO CHIAT ROAD 427588 CARNE BURGERS 88 AMOY ST 069907 CULTURE SPOON 409 RIVER VALLEY ROAD 248307 DAWN'S GELATERIA 106 CLEMENTI ST 12 #01-38 120106 DAYA IZAKAYA 254 JALAN KAYU 799481 DEVIL CHICKEN 2 JURONG EAST CENTRAL 1 , JCUBE B1-K10 609731 1 NORTHPOINT DRIVE, NORTHPOINT CITY B2-126 768019 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD #B2-258 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 EATCETERA 12 ALEXANDRA VIEW #01-02/03/04 158736 FO YOU YUAN VEGETARIAN 310 LAVENDER STREET #01-01 338815 RESTAURANT FOUNTAIN MICROBREWERY 21 JURONG TOWN HALL ROAD LEVEL 2 SNOW CITY 609433 FUSEZ GRILL & BAR 20 CECIL STREET #01-06, PLUS BUILDING 49705 GELATO LABO 11 CAVAN ROAD #01-09 CAVAN SUITES 209848 18 MOHAMMED SULTAN ROAD #01-10 238967 108 FABER DRIVE 129418 GLASS ROASTERS 18 MOHAMMED SULTAN ROAD #01-10 238967 108 FABER DRIVE 129418 HAJIME TONKATSU & RAMEN 1 MAJU AVENUE 02 - 7/8/9 MYVILLAGE AT SERANGOON 556679 GARDEN 301 UPPER THOMSON ROAD #01-110 THOMSON PLAZA 574408 HOUSE DOWNSTAIRS 170 GHIM MOH ROAD #01-03 279621 HOUSE OF YAM 205 HOUGANG STREET 21 #03-18/19 530205 ITAEWON