Caring for Your Lizard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Herpetology Papers in the Biological Sciences 1993 Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska? Louis A. Somma Florida State Collection of Arthropods, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Population Biology Commons Somma, Louis A., "Do Worm Lizards Occur in Nebraska?" (1993). Papers in Herpetology. 11. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosciherpetology/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Herpetology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. @ o /' number , ,... :S:' .' ,. '. 1'1'13 Do Mono Li ••rel,. Occur ill 1!I! ..br .... l< .. ? by Louis A. Somma Department of- Zoology University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 Amphisbaenids, or worm lizards, are a small enigmatic suborder of reptiles (containing 4 families; ca. 140 species) within the order Squamata, which include~ the more speciose lizards and snakes (Gans 1986). The name amphisbaenia is derived from the mythical Amphisbaena (Topsell 1608; Aldrovandi 1640), a two-headed beast (one head at each end), whose fantastical description may have been based, in part, upon actual observations of living worm lizards (Druce 1910). While most are limbless and worm-like in appearance, members of the family Bipedidae (containing the single genus Sipes) have two forelimbs located close to the head. This trait, and the lack of well-developed eyes, makes them look like two-legged worms. -

Habitat Selection of the Desert Night Lizard (Xantusia Vigilis) on Mojave Yucca (Yucca Schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California

Habitat selection of the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis) on Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera) in the Mojave Desert, California Kirsten Boylan1, Robert Degen2, Carly Sanchez3, Krista Schmidt4, Chantal Sengsourinho5 University of California, San Diego1, University of California, Merced2, University of California, Santa Cruz3, University of California, Davis4 , University of California, San Diego5 ABSTRACT The Mojave Desert is a massive natural ecosystem that acts as a biodiversity hotspot for hundreds of different species. However, there has been little research into many of the organisms that comprise these ecosystems, one being the desert night lizard (Xantusia vigilis). Our study examined the relationship between the common X. vigilis and the Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera). We investigated whether X. vigilis exhibits habitat preference for fallen Y. schidigera log microhabitats and what factors make certain log microhabitats more suitable for X. vigilis inhabitation. We found that X. vigilis preferred Y. schidigera logs that were larger in circumference and showed no preference for dead or live clonal stands of Y. schidigera. When invertebrates were present, X. vigilis was approximately 50% more likely to also be present. These results suggest that X. vigilis have preferences for different types of Y. schidigera logs and logs where invertebrates are present. These findings are important as they help in understanding one of the Mojave Desert’s most abundant reptile species and the ecosystems of the Mojave Desert as a whole. INTRODUCTION such as the Mojave Desert in California. Habitat selection is an important The Mojave Desert has extreme factor in the shaping of an ecosystem. temperature fluctuations, ranging from Where an animal chooses to live and below freezing to over 134.6 degrees forage can affect distributions of plants, Fahrenheit (Schoenherr 2017). -

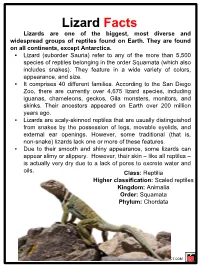

Lizard Facts Lizards Are One of the Biggest, Most Diverse and Widespread Groups of Reptiles Found on Earth

Lizard Facts Lizards are one of the biggest, most diverse and widespread groups of reptiles found on Earth. They are found on all continents, except Antarctica. ▪ Lizard (suborder Sauria) refer to any of the more than 5,500 species of reptiles belonging in the order Squamata (which also includes snakes). They feature in a wide variety of colors, appearance, and size. ▪ It comprises 40 different families. According to the San Diego Zoo, there are currently over 4,675 lizard species, including iguanas, chameleons, geckos, Gila monsters, monitors, and skinks. Their ancestors appeared on Earth over 200 million years ago. ▪ Lizards are scaly-skinned reptiles that are usually distinguished from snakes by the possession of legs, movable eyelids, and external ear openings. However, some traditional (that is, non-snake) lizards lack one or more of these features. ▪ Due to their smooth and shiny appearance, some lizards can appear slimy or slippery. However, their skin – like all reptiles – is actually very dry due to a lack of pores to excrete water and oils. Class: Reptilia Higher classification: Scaled reptiles Kingdom: Animalia Order: Squamata Phylum: Chordata KIDSKONNECT.COM Lizard Facts MOBILITY All lizards are capable of swimming, and a few are quite comfortable in aquatic environments. Many are also good climbers and fast sprinters. Some can even run on two legs, such as the Collared Lizard and the Spiny-Tailed Iguana. LIZARDS AND HUMANS Most lizard species are harmless to humans. Only the very largest lizard species pose any threat of death. The chief impact of lizards on humans is positive, as they are the main predators of pest species. -

Meet the Herps!

Science Standards Correlation SC06-S2C2-03, SC04-S4C1-04, SC05-S4C1-01, SC04-S4C1-06, SC07-S4C3-02, SC08- S4C4-01, 02&06 MEET THE HERPS! Some can go without a meal for more than a year. Others can live for a century, but not really reach a ripe old age for another couple of decades. One species is able to squirt blood from its eyes. What kinds of animals are these? They’re herps – the collective name given to reptiles and amphibians. What Is Herpetology? The word “herp” comes from the word “herpeton,” the Greek word for “crawling things.” Herpetology is the branch of science focusing on reptiles and amphibians. The reptiles are divided into four major groups: lizards, snakes, turtles, and crocodilians. Three major groups – frogs (including toads), salamanders and caecilians – make up the amphibians. A herpetologist studies animals from all seven of these groups. Even though reptiles and amphibians are grouped together for study, they are two very different kinds of animals. They are related in the sense that early reptiles evolved from amphibians – just as birds, and later mammals, evolved from reptiles. But reptiles and amphibians are each in a scientific class of their own, just as mammals are in their own separate class. One of the reasons reptiles and amphibians are lumped together under the heading of “herps” is that, at one time, naturalists thought the two kinds of animals were much more closely related than they really are, and the practice of studying them together just persisted through the years. Reptiles vs. Amphibians: How Are They Different? Many of the differences between reptiles and amphibians are internal (inside the body). -

Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles)

6-3.1 Compare the characteristic structures of invertebrate animals... and vertebrate animals (fish, amphibians, and reptiles). Also covers: 6-1.1, 6-1.2, 6-1.5, 6-3.2, 6-3.3 Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles sections Can I find one? If you want to find a frog or salamander— 1 Chordates and Vertebrates two types of amphibians—visit a nearby Lab Endotherms and Exotherms pond or stream. By studying fish, amphib- 2 Fish ians, and reptiles, scientists can learn about a 3 Amphibians variety of vertebrate characteristics, includ- 4 Reptiles ing how these animals reproduce, develop, Lab Water Temperature and the and are classified. Respiration Rate of Fish Science Journal List two unique characteristics for Virtual Lab How are fish adapted each animal group you will be studying. to their environment? 220 Robert Lubeck/Animals Animals Start-Up Activities Fish, Amphibians, and Reptiles Make the following Foldable to help you organize Snake Hearing information about the animals you will be studying. How much do you know about reptiles? For example, do snakes have eyelids? Why do STEP 1 Fold one piece of paper lengthwise snakes flick their tongues in and out? How into thirds. can some snakes swallow animals that are larger than their own heads? Snakes don’t have ears, so how do they hear? In this lab, you will discover the answer to one of these questions. STEP 2 Fold the paper widthwise into fourths. 1. Hold a tuning fork by the stem and tap it on a hard piece of rubber, such as the sole of a shoe. -

Komodo Dragon (Read-Only)

Komodo Dragons A Komodo dragon is the largest lizard living anywhere in the world. Do you know how big it can get? It can grow to be 10 feet long and over 175 pounds. That’s a giant reptile! It only lives on a few islands near Indonesia. Komodo dragons have long, powerful tails. They also have long claws on their feet. Their mouth is full of sharp teeth. When a tooth breaks off, another one will grow in. Some komodo dragons grow up to 200 new teeth in a year! This lizard can smell food over a mile away. They are carnivores, which means they eat meat. They will eat deer, birds, and other mammals. They can swim well, so sometimes they find their prey in the ocean. Scientists are studying these fascinating animals to learn more about how they live. Scan here to learn more about komodo dragons. Purposefully Primary 2014 Name ___________________ Lizards Scan here to What type of learn more animal is a lizard A lizard is a type of reptile. It is closely about lizards! ? related to snakes, but a lizard usually has legs. _________________ It also has a short body and a long tail. What do lizards eat? _________________ Most lizards are harmless to people. In _________________ Highlight the fact, some people even keep lizards as pets! answer with _________________ yellow. A lizard will eat insects, fruits and vegetables. It’s helpful to have an insect-eating lizard in _________________ Why is a lizard your garden. Highlight the answer colorful? with green. Lizards can be very colorful, and all _________________ different shapes and sizes. -

Life History Account for Island Night Lizard

California Wildlife Habitat Relationships System California Department of Fish and Wildlife California Interagency Wildlife Task Group ISLAND NIGHT LIZARD Xantusia riversiana Family: XANTUSIIDAE Order: SQUAMATA Class: REPTILIA R035 Written by: R. Marlow Reviewed by: T. Papenfuss Edited by: R. Duke, J. Harris DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND SEASONALITY The island night lizard is presently known from three of the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California: San Clemente, Santa Barbara and San Nicolas. It may occur on other Channel Islands and has been reported from Santa Catalina, but these reports have not been substantiated (Stebbins 1954). These three islands provide a variety of habitats from coastal strand and sand dunes to chaparral and woodlands, and the lizards are found in all habitats that provide cover in great abundance (Stebbins 1954, Mautz and Case 1974). SPECIFIC HABITAT REQUIREMENTS Feeding: This species is omnivorous. It eats insects (silverfish, caterpillars, moths, ants, etc.), plants (up to 50% by volume) and possibly small mammals (Schwenkmeyer 1949, Knowlton 1949, Brattstrom 1952, Stebbins 1954). This lizard seems to be a food generalist and opportunist, taking advantage of whatever food source is available in an environment with few, if any, competitors. Cover: This species, like other members of this family, makes extensive use of cover. It is seldom observed on the surface in the open, but usually under objects or moving through thick vegetation, or around cover. It utilizes prostrate plant cover, the extensive patches of Opuntia or ice plant found on these islands, as well as rocks, logs and rubble (Stebbins 1954). Adequate cover in the form of vegetation, rock rubble, logs or other objects is probably the most important habitat requirement. -

Crypsis Decreases with Elevation in a Lizard

diversity Article Crypsis Decreases with Elevation in a Lizard Gregorio Moreno-Rueda * , Laureano G. González-Granda, Senda Reguera, Francisco J. Zamora-Camacho and Elena Melero Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de Granada, E-18071 Granada, Spain; [email protected] (L.G.G.-G.); [email protected] (S.R.); [email protected] (F.J.Z.-C.); [email protected] (E.M.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 7 November 2019; Accepted: 5 December 2019; Published: 7 December 2019 Abstract: Predation usually selects for visual crypsis, the colour matching between an animal and its background. Geographic co-variation between animal and background colourations is well known, but how crypsis varies along elevational gradients remains unknown. We predict that dorsal colouration in the lizard Psammodromus algirus should covary with the colour of bare soil—where this lizard is mainly found—along a 2200 m elevational gradient in Sierra Nevada (SE Spain). Moreover, we predict that crypsis should decrease with elevation for two reasons: (1) Predation pressure typically decreases with elevation, and (2) at high elevation, dorsal colouration is under conflicting selection for both crypsis and thermoregulation. By means of standardised photographies of the substratum and colourimetric measurements of lizard dorsal skin, we tested the colour matching between lizard dorsum and background. We found that, along the gradient, lizard dorsal colouration covaried with the colouration of bare soil, but not with other background elements where the lizard is rarely detected. Moreover, supporting our prediction, the degree of crypsis against bare soil decreased with elevation. Hence, our findings suggest local adaptation for crypsis in this lizard along an elevational gradient, but this local adaptation would be hindered at high elevations. -

Reptiles Silvery Legless Lizard (Anniella Pulchra Pulchra)

Reptiles Silvery Legless Lizard (Anniella pulchra pulchra) Silvery Legless Lizard (Anniella pulchra pulchra) Status State: Species of Concern Federal: None Population Trend Global: Declining State: Declining Within Inventory Area: © 1998 William Flaxington Unknown Data Characterization The location database for the silvery legless lizard (Anniella pulchra pulchra) within its known range in California includes 14 data records dated from 1988 to 2000. Of these records, 12 were documented within the past 10 years; of these, 9 are of high precision and may be accurately located. One of these records is located within the inventory area, at the East Bay Regional Park District Legless Lizard Preserve. A small amount of literature is available for the silvery legless lizard because of its cryptic behavior and general difficulty to find. Most of the available literature pertains to natural history and reproductive patterns. Range The silvery legless lizard is nearly endemic to California. It ranges from Antioch in Contra Costa County south through the Coast, Transverse, and Peninsular Ranges, along the western edge of the Sierra Nevada Mountains and parts of the San Joaquin Valley and Mojave Desert to El Consuelo in Baja California (Hunt 1983, Jennings and Hayes 1994). Its elevation range extends from near sea level on the Monterey Peninsula to approximately 1,800 meters above sea level in the Sierra Nevada foothills. Occurrences within the ECC HCP Inventory Area The East Bay Regional Park District Legless Lizard Preserve is located east of the intersection of Highway 4 and Big Break Road north of Oakely. This is the only California Natural Diversity Database record for this species in the inventory area, but other occurrences are likely to exist within the inventory area due to the presence of suitable habitat. -

St. Croix Ground Lizard Ameiva Polops

St. Croix Ground Lizard Ameiva polops Distribution Habitat The species’ habitat includes forested, woodland, and shrub land areas. The species is most commonly found in sandy areas and patches of direct sunlight, on the ground, or in low canopy cover and leaf litter (fallen leaves). Ground lizards spend most of their time foraging and thermoregulating. Other activities include aggressive interactions among individuals, mating, and burrowing behavior. Diet Family: Teiidae Individuals actively forage within leaf litter (fallen Order: Squamata leaves) and loosely compacted soils for a variety of invertebrates such as centipedes, moths, arthropods, hermit crabs, sand fleas, and segmented worms. Description Distribution The St. Croix ground lizard (Ameiva polops) is a small The lizard populations previously existed on the island lizard that can measure between 14 to 30 inches (35 of St. Croix, United States Virgin Islands, and other - 77 mm) in length. It features wide dorsal striping, adjacent cays. The ground lizard is presumed extinct a pink throat and white or cream ventral area. Male in St. Croix. The last report of the species in the main lizards have blue and white colored scales mottled island of St. Croix was in 1968. Currently native below their tan and brown dorsal stripes. The lizard’s populations occur in the offshore cays of Protestant tail is longer than its body length and the tail is ringed Cay and the Green Cay National Wildlife Refuge. Two with alternating blue and white bands. Juveniles have additional populations have been established through bright blue tails, and the tail coloration fades with age. a translocation program in Ruth Cay and Buck Island Male lizards are larger than females. -

Dunes Sagebrush Lizard Petition

1 May 8, 2018 Mr. Ryan Zinke Secretary of the Interior Office of the Secretary Department of the Interior 18th and “C” Street, N.W. Washington DC 20202 Subject: Petition to List the Dunes Sagebrush Lizard as a Threatened or Endangered Species and Designate Critical Habitat Dear Secretary Zinke: The Center for Biological Diversity and Defenders of Wildlife hereby formally petition to list the dunes sagebrush lizard (Sceloperus arenicolus) as a threatened or endangered species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (16 U.S.C. 1531 et seq.). This petition is filed under 5 U.S.C. § 553(e) and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14, which grant interested parties the right to petition for the issuance of a rule from the Assistant Secretary of the Interior. The Petitioners also request that critical habitat be designated for S. arenicolus concurrent with the listing, as required by 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b)(6)(C) and 50 C.F.R. § 424.12, and pursuant to the Administrative Procedures Act (5 U.S.C. § 553). The Petitioners understand that this petition sets in motion a specific process, placing defined response requirements on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and specific time constraints on those responses. See 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b). Petitioners The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, non-profit conservation organization with more than 1.6 million members and online activists dedicated to protecting diverse native species and habitats through science, policy, education, and the law. It has offices in 11 states and Mexico. -

Observations of Infanticide and Cannibalism in Four Species of Cordylid Lizard (Squamata: Cordylidae) in Captivity and the Wild

Herpetology Notes, volume 14: 725-729 (2021) (published online on 21 April 2021) Observations of infanticide and cannibalism in four species of cordylid lizard (Squamata: Cordylidae) in captivity and the wild Daniel van Blerk1,†, Jens Reissig2,†, Julia L. Riley 3,†, John Measey1,*, and James Baxter-Gilbert1 Cannibalism, the consumption of conspecifics, of Africa (Reissig, 2014), from Ethiopia to South Africa is taxonomically widespread and occurs across a (latitudinally) and Angola to Ethiopia (longitudinally). diversity of reptilian species (Polis and Myers, 1985). Here, we present observations of cannibalism by four A long-standing, yet antiquated, perspective views species of cordylid lizard, two from free-living wild cannibalism as an aberrant behaviour (as discussed populations and another two from captive settings. Since in Fox, 1975), but contemporary investigations have the natural history of many cordylid species remains noted its important role in the ecology and evolution of deficient, and several species have been observed to many wild populations (Robbins et al., 2013; Cooper display reasonably high degrees of sociality, like group- et al., 2015; Van Kleek et al., 2018). Examples of this living in Armadillo Lizards, Ouroborus cataphractus include habitat partitioning and optimising resource (Boie, 1828) (Mouton, 2011) and Sungazers, Smaug availability, as seen in juvenile Komodo Dragons, giganteus (Smith, 1844) (Parusnath, 2020), these Varanus komodoensis Ouwens, 1912, taking to the trees observations provide important insights