Making Theatre Elastic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

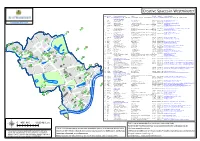

Creative Spaces in Westminster

Creative Spaces in Westminster Map Facilities Company/organisation name Address Postcode Telephone For more information Key: C = cultural and community event; E = exhibitions; F = film / photography / cinema; L = launch, fashion show, reception; M = meeting / class / workshop; P = performance; R = audition / rehearsal Large Mixed Use Spaces 1 C, M Abbey Community Centre 34 Great Smith Street SW1P 3BU 020 7222 0303 www.theabbeycentre.org.uk/venue/ 2 M, P, R Amadeus Centre 50 Shirland Road W9 2JA 020 7286 1686 www.amadeuscentre.co.uk Corporate GIS Team 3 C, E, M, R Beethoven Centre Third Avenue Queens Park W10 4LJ 020 8825 1067 www.a2dominion.co.uk/rte.asp?id=984 4 Natural History Museum contact the Arts and Culture Service - 020 7641 2498 SW7 5BD www.nhm.ac.uk/ 5 C, E, M, P, R Paddington Arts 32 Woodfield Road W9 2BE 020 7286 2722 www.paddingtonarts.org.uk/roomhire.php 6 M, P, R Royal Academy of Music Marylebone Road NW1 5HT 020 7873 7373 www.ram.ac.uk/venue-hire 21 7 E, L, M Royal College of Art Kensington Gore SW7 2EU 020 7590 4118 www.rca.ac.uk/Default.aspx?ContentID=159651&groupID=159651 8 Royal Geographical Society contact the Arts and Culture Service - 020 7641 2498 SW7 2AR www.rgs.org/HomePage.htm 9 M, R Rudolf Steiner House 35 Park Road NW1 6XT 020 7723 4400 www.rsh.anth.org.uk/pages/house_fac.html 15 10 Science Museum contact the Arts and Culture Service - 020 7641 2498 SW7 2DD www.sciencemuseum.org.uk/ 11 E, L, M, P, R Tabernacle 34-35 Powis Square W11 2AY 020 7221 9700 www.tabernaclew11.com/rooms-for-hire/ 12 Victoria & Albert -

Diary September 2018.Rtf

Diary September 2018 Sat 1 Lambeth Local History Fair Omnibus, 1 Clapham Common North Side, SW4, 10.15am–4.15pm (to 30) Lambeth Heritage Festival Month LHF: West Norwood Cemetery’s Clapham Connections, Omnibus Theatre, SW4, 10.45am National Trust: Quacky Races on the Wandle, Snuff Mill, Morden Hall Park, 11am-3pm LWT: Great North Wood Walk, Great North Wood team, Sydenham Hill station, College Rd, noon LHF: Rink Mania in Edwardian Lambeth, Sean Creighton, Omnibus Theatre, SW4, 12.30pm LHF: Clapham Library to Omnibus Theatre, Peter Jefferson Smith & Marie McCarthy, 1.30pm Godstonebury Festival, Orpheus Centre, North Park Lane, Godstone, 12-8pm SCOG: 36 George Lane, Hayes, BR2 7LQ, 2-8pm Laurel and Hardy Society: The Live Ghost Tent, Cinema Musum, 3pm LHF: 1848 Kennington Common Chartists’ Rally, Marietta Crichton Stuart & Richard Galpin, 3.15pm Sun 2 NGS: Royal Trinity Hospice, 30 Clapham Common North Side, 10am-4.30pm Streatham’s Art-Deco & Modernism Walk, Adrian Whittle, Streatham Library, 10.30am Streatham Kite Day, Streatham Common, 11am-5pm Historic Croydon Airport Trust: Open Day, 11am-4pm Shirley Windmill: Open Day, Postmill Close, Croydon, 12-5pm Crystal Palace Museum: Guided tour of the historic Crystal Palace grounds, noon Streatham Society: Henry Tate Gardens Tour, Lodge gates, Henry Tate Mews, SW16, 2 & 3pm NGS: 24 Grove Park, Camberwell, SE5 8LH, 2-5.30pm Kennington Talkies: After the Thin Man (U|1936|USA|110 min), Cinema Musum, 2.30pm Herne Hill S'y: South Herne Hill Heritage Trail, Robert Holden, All Saints’ Ch, Lovelace -

Diary October 2018.Rtf

Diary October 2018 Mon 1 Ashburton Library: The Nostradamus of South Norwood Hill, Stephen Oxford, 11am Dulwich Library Film Club: Babylon (15|1980|UK|91 mins), 1.30pm BIS: Cellini's Gold Salt-Cellar, Dr Charles Avery, Oxford & Cambridge Club, 71 Pall Mall, SW1, 7pm CNHSS: Lapis Lazuli, Chris Duffin, ECURC, 7.45pm (to 31) London Month of the Dead SCLS: Steaming On: Train Travel on the UK's Preserved Railways, Paul Whittle, RURC, 7.45pm Streatham S'y: Being Leader of the Opposition on Lambeth Council, Tim Briggs, Woodlawns, 8pm (to 6) Theatre 62: The Prisoner of Second Avenue by Neil Simon, Wickham Theatre Centre, 8pm Tue 2 Age UK: Older People's Day 2018, Scratchley Hall, Brigstock Road, Thornton Heath, 11am-4pm Silver Cinema: Patrick (PG|2018|USA|94 mins), Odeon, Beckenham, 11am Victory Club: Tea Dance, Brian Pasby, 227 Selhurst Road, South Norwood, SE25 6XY, 2-4pm Silver Cinema: Edie (12A|2018|UK|101 mins), Odeon, Beckenham, 2pm Handel in London: The Making of a Genius, Professor Jane Glover, Southwark Cathedral, 7pm LCI: London Bridge Redevelopment, Liam Farrell, 55 Broadway, 6pm LWT: Woodland Industry & Deptford Shipyards, Edwin Malins, Festa sul Prato, Deptford, 7.30pm DLC: The Heiresses (12A|2018|Spain|98 mins|subtitled), 7.30pm LMOD: The Future of Death, John Troyer, Highgate Cemetery Chapel, 7.30pm COPSE: Bumblebees, Nikki Gammans, United Church, Aberdeen Road, South Croydon, 8.15pm BBLHS: Bromley Workhouse: Sad Life of Amelia Dolding , Stuart Valentine, Trinity URC, 7.45pm SMLS: The John Gent Postcard Collection part 2, John Hickman, -

Great New Travel Discounts for Rescard Holders!

AUTUMN EDITION 2006 Issue 66 Great new travel discounts for ResCard holders! A service provided for Westminster City Council by Metropolis International (UK) Limited Autumn in Westminster throughout the year. Having basked in the heat of the Call 020 summer months, it will soon be 7641 1200 to time to embrace the Autumn. So, find out why not make the most of the more. new season by taking advantage If you have of the wide range of activities and a taste for offers available with your ResCard. embroidery Art has many guises, and so the then the Masterclass at the Theatre Royal Hellenic Haymarket could be what you’re Centre looking for. Young people aged 17 could be for - 30 years, with an interest in you. From 13th October to 16th drama, can attend free events, put November various 17th to 19th on by the theatre, including a Century Greek embroideries, from class held by Nicolas Hytner, the collections of the V&A Artistic Director of the National museum and Benaki Museum in Theatre on 20th September at Athens, are being shown for the 2.30pm. Another class will also be first time in 100 years. This is a held by Edward Hall, Associate once in a lifetime opportunity to Director of The Old Vic Theatre, on view these superb works. For more 9th October at 2.30pm. Visit information call 020 7487 5060 or www.trh.co.uk/masterclass for visit www.helleniccentre.com more information. If you are aged 18 - 35 years and There are sport and leisure offers have the travel bug, then a plenty with your ResCard this perhaps you should take season. -

Eurythmy-Newsletter

mer 2 Newsletter Sum 020 of the Eurythmy Association of Great Britain and Ireland Editorial Team: Christopher Elisabeth Bamford Kidman [email protected] The Newsletter in Extraordinary Times! Dear Readers, We hope you enjoy the Summer Newsletter! This strange Wishing you all good health, resilience, and courage for time has produced all manner of interesting articles! The the next step! coronavirus lockdown follows hot on the heels of Ofsted’s Warm greetings, pressure on our Waldorf schools, which itself caused Elisabeth damage to eurythmy work. Our sympathy goes to all of you whose work has been disrupted. First of all, we have some colourful reports of events and performances prior to lockdown. Let’s bathe in the memory! CONTENTS The present crisis has elicited a variety of contributions News from the Council ..............................2 about people’s personal practice and reflection, as well Planetary Seals Course ............................2 as accounts of working in unfamiliar conditions, and Spring Valley Ensemble ............................4 experiences of teaching eurythmy online. Thank you so much for taking the trouble to express many aspects of News from Ireland .....................................5 this work for us. The Performing Arts Section .....................6 How the word screen has changed its meaning! In the past, How eurythmists can help professional a screen meant privacy, secrecy, even the possibility of carers in residential care homes .............7 eavesdropping (beloved by playwrights!). Now the screen is a communicator, a sort of portal! Some contributions about eurythmy in the Some inspiring memories of Marguerite Lundgren’s time of coronavirus ....................................9 eurythmy teaching are shared by two of her former Several experiences with eurythmy students, and we hope to be able to bring you further online ....................................................... -

DIUS Register Final Version

Register of Education and Training Providers as last maintained by the Department of Innovation, Universities and Skills on the 30 March 2009 College Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode Telephone Email 12 training 1 Sherwood Place, 153 Sherwood DrivBletchley, Milton Keynes Bucks MK3 6RT 0845 605 1212 [email protected] 16 Plus Team Ltd Oakridge Chambers 1 - 3 Oakridge Road BROMLEY BR1 5QW 1st Choice Training and Assessment Centre Ltd 8th Floor, Hannibal House Elephant & Castle London SE1 6TE 020 7277 0979 1st Great Western Train Co 1st Floor High Street Station Swansea SA1 1NU 01792 632238 2 Sisters Premier Division Ltd Ram Boulevard Foxhills Industrial Estate SCUNTHORPE DN15 8QW 21st Century I.T 78a Rushey Green Catford London SE6 4HW 020 8690 0252 [email protected] 2C Limited 7th Floor Lombard House 145 Great Charles Street BIRMINGHAM B3 3LP 0121 200 1112 2C Ltd Victoria House 287a Duke Street, Fenton Stoke on Trent ST4 3NT 2nd City Academy City Gate 25 Moat Lane Digbeth, Birmingham B5 5BD 0121 622 2212 2XL Training Limited 662 High Road Tottenham London N17 0AB 020 8493 0047 [email protected] 360 GSP College Trident Business Centre 89 Bickersteth Road London SW17 9SH 020 8672 4151 / 084 3E'S Enterprises (Trading) Ltd Po Box 1017 Cooks Lane BIRMINGHAM B37 6NZ 5 E College of London Selby Centre Selby Road London N17 8JL 020 8885 3456 5Cs Training 1st Floor Kingston Court Walsall Road CANNOCK WS11 0HG 01543 572241 6S Consulting Limited c/o 67 OCEAN WHARF 60 WESTFERRY ROAD LONDON E14 8JS 7city Learning Ltd 4 Chiswell -

North London

North London IN THIS ISSUE Children’s Parties Education Parenting Plus What’s On, Easter Fun and much more inside! Issue 129 March/April 2018 familiesonline.co.uk Growing Family? Moving into your next home. Buying your first home was an exciting, nerve racking experience and a leap of faith onto the property ladder. Buying your next home, when your family is expanding, can be equally as exciting yet challenging at the same time. You may be embarking on the next chapter of your life when two become three, or maybe a further new arrival is on its way. Buying and selling a home together and becoming part of a “chain” of transactions can become frustrating and mysterious, with numerous buyers and sellers involved. A longer chain means more people involved and it may potentially take longer for everyone to be ready to exchange contracts and agree a completion date. If one party delays then the whole chain will be delayed, so be patient and make sure your agent can provide you with regular updates on the whole chain and not just your property. This is so that you can realistically manage your expectations as to when you will be moving. Moving in the early years of your children’s life will mean that you are able to make sure that your new home is within the catchment area of the perfect school for your children. When planning your move, it is important to factor in that it will take around 12-16 weeks from a sale being agreed to the actual move in date. -

North London

North London IN THIS ISSUE Education and School Feature Issue Plus Local Clubs and Classes WIN a term of swimming lessons with Swimming Nature See page 8 Plus What’s On, Children’s Theatre and much more! Issue 132 September/October 2018 familiesonline.co.uk Welcome to the September/October issue! CONTACT US: UPCOMING ISSUES IN THIS ISSUE: Nov/Dec 2018 — “Seasonal 2 Families News Celebrations, Families North London 4 Independent Schools Pantos” IN THIS ISSUE Open Days North London Education and Deadline : School Feature Issue Plus Local Clubs and Classes 6 Education 1 October 2018 WIN a term of swimming lessons with Swimming Magazine Nature See page 8 10 Family Health Plus What’s On, Children’s Send in your Theatre and much more! Publisher: Karen Konowalchuk 10 Parties, Clubs Classes Managing Editor: Lisa Ralph news, stories and advertising & Activities PO Box 74501, Muswell Hill N10 9DZ bookings to the Issue 132 September/October 2018 familiesonline.co.uk 16 What’s On T: 020 8793 3366 details left. Front cover image credit M: 07402 613 042 Jenny Smith Photography 18 Children’s Theatre E: [email protected] jennysmithphotography.co.uk E: [email protected] www.FamiliesNorthLondon.co.uk FamiliesNorthLondon FamiliesNthLon FamiliesNorthLondon HADLEY WOOD M25 WHERE IS FAMILIES NORTH LONDON? TRENT PARK HIGH BARNET CLAY HILL M1 COCKFOSTERS ENFIELD PONDERS END Families North London Magazine is distributed bi-monthly throughout North London. ARKLEY EAST BARNET TOTTERIDGE WINCHMORE HILL An area bordered by the M1/A5 on the West, the A112/A10 on the East, the M25 to the MILL HILL WHETSTONE SOUTHGATE LOWER EDMONTON ARNOS GROVE North and the A501 to the South. -

Open House London Guide 2016

48 4 Listings Key to listings Ballots A Architect on site Address of the building The following buildings / meeting point and events are only Bookshop B accessible by entering Opening times C Children’s activities our public ballot: Nearest tube/rail station d Some disabled access 10 Downing Street → p131 Useful bus routes D Full wheelchair access Arcelormittal Orbit → p107 Occasional boat trip The Shard → p119 E Engineer on site G Green Features The ballots will be open f r o m 18 –31 August. Go to Normally open to the N openhouselondon.org.uk/ public free of charge ballots to enter. Please note, P Parking only successful applicants will be notified. Q Long queues envisaged R Refreshments T Toilets The programme listings on the following pages Barking & Dagenham → p49, Barnet → p51, Brent are ordered by borough area. Open House → p53, Camden → p55, City of London → p 61, London is in part funded by individual local Croydon → p67, Ealing → p69, Enfield → p71, authorities. Unfortunately Bexley, Bromley and Greenwich → p73, Hackney → p76, Hammersmith Kingston-upon-Thames are not participating & Fulham → p80, Haringey → p82, Harrow → p85, this year. Lobby your local councillors to ensure Havering → p87, Hillingdon → p89, Hounslow their inclusion next year! The index (→ p140) lists → p91, Islington → p93, Kensington & Chelsea buildings by type. You can also use our online → p96, Lambeth → p99, Lewisham → p102, Merton search facility at openhouselondon.org.uk/search → p105, Newham → p107, Redbridge → p110, and our app to find the buildings you want to visit. Richmond → p112 , Southwark → p115, Sutton All access to buildings is on a first come basis → p120, Tower Hamlets → p122, Waltham Forest unless otherwise specified.