European Black Slug

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invasive Alien Slug Could Spread Further with Climate Change

Invasive alien slug could spread further with climate change A recent study sheds light on why some alien species are more likely to become invasive than others. The research in Switzerland found that the alien Spanish slug is better able to survive under changing environmental conditions than the native 20 December 2012 Black slug, thanks to its robust ‘Jack-of-all-trades’ nature. Issue 311 Subscribe to free weekly News Alert Invasive alien species are animals and plants that are introduced accidently or deliberately into a natural environment where they are not normally found and become Source: Knop, E. & dominant in the local ecosystem. They are a potential threat to biodiversity, especially if they Reusser, N. (2012) Jack- compete with or negatively affect native species. There is concern that climate change will of-all-trades: phenotypic encourage more invasive alien species to become established and, as such, a better plasticitiy facilitates the understanding is needed of why and how some introduced species become successful invasion of an alien slug invaders. species. Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological The study compared the ‘phenotypic plasticity’ of a native and a non-native slug species in Sciences. 279: 4668-4676. Europe. Phenotypic plasticity is the ability of an organism to alter its characteristics or traits Doi: (including behaviour) in response to changing environmental conditions. 10.1098/rspb.2012.1564. According to a framework used to understand invasive plants, invaders can benefit from phenotypic plasticity in three ways. Firstly, they are robust and can maintain fitness in Contact: varied, stressful situations, and are described as ‘Jack-of-all-trades’. -

Biological Inventory of Blaauw ECO Forest – NWD Plan 1560 (Township of Langley)

Biological Inventory of Blaauw ECO Forest – NWD Plan 1560 (Township of Langley): Including vertebrates, vascular plants, select non-vascular plants, and select invertebrates Curtis Abney Student #430748 April 21st, 2014 Thesis Advisor: Dr. D. Clements Co-Advisor: Prof. K. Steensma 1 Abstract Preserving the earth’s remaining biodiversity is a major conservation concern. Especially in areas where urban development threatens to take over prime species habitat, protecting green spaces can be an effective method for conserving local biodiversity. Establishing biological inventories of these green species can be crucial for the appropriate management of them and for the conservation of the species which use them. This particular study focused on a recently preserved forest plot, just 25 acres in size, which is now known as the Blaauw ECO Forest. The Blaauw ECO Forest was acquired by Trinity Western University in 2013 to serve as an ecological preserve where students and staff can conduct ecological research and conservation work. After ten months of research and over 100 hours of onsite observations, over 250 species of flora and fauna have been documented inhabiting or using the forest (e.g. as a breeding site). Throughout the duration of this study, several large mammals such as coyotes (Canis latrans), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), and black bears (Ursus americanus) have been documented using the forest which highlights the forest’s use as patch habitat. Several provincially blue- listed species have also been seen in the forest, the Pacific Sideband snail (Monadenia fidelis) and Northern Red-legged Frog (Rana aurora) in particular, and these species may testify to the forest’s rich ecology. -

Slug: an Emerging Menace in Agriculture: a Review

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2020; 8(4): 01-06 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 www.entomoljournal.com Slug: An emerging menace in agriculture: A JEZS 2020; 8(4): 01-06 © 2020 JEZS review Received: 01-05-2020 Accepted: 03-06-2020 Partha Pratim Gyanudoy Das, Badal Bhattacharyya, Sudhansu Partha Pratim Gyanudoy Das All India Network Project on Bhagawati, Elangbam Bidyarani Devi, Nang Sena Manpoong and K Soil Arthropod Pests, Sindhura Bhairavi Department of Entomology, Assam Agricultural University, Jorhat, Assam, India Abstract Most of the terrestrial slugs are potential threat to agriculture across the globe. Their highly adaptive Badal Bhattacharyya nature helps them to survive in both temperate and tropical climates which is one of the major reasons of All India Network Project on its abundant species diversity. It is not only a severe problem in different seedlings of nursery and Soil Arthropod Pests, orchards, also a worry factor for the seeds of legumes sown in furrows. The whitish slimy mucus Department of Entomology, generated by this pest makes the flower and vegetables unfit for sale. However, despite of its euryphagic Assam Agricultural University, nature, very few works have been carried out on slug morphology, biology, ecology, taxonomy and its Jorhat, Assam, India management in India. This review article tries to integrate the information of economically important slug species of the world as well as India, their bio-ecology, nature of damage, favorable factors with Sudhansu Bhagawati special emphasis on eco-friendly management tactics of this particular gastropod pest. All India Network Project on Soil Arthropod Pests, Keywords: Slug, euryphagic, bio-ecology, management, gastropod pest Department of Entomology, Assam Agricultural University, Jorhat, Assam, India Introduction With a number of 80,000 to 135,000 members, mollusc ranks second largest invertebrate Elangbam Bidyarani Devi group in the world, out of which 1129 species of terrestrial molluscs are found in India [1, 2, 3]. -

Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L

EENY-494 Terrestrial Slugs of Florida (Gastropoda: Stylommatophora)1 John L. Capinera2 Introduction Florida has only a few terrestrial slug species that are native (indigenous), but some non-native (nonindigenous) species have successfully established here. Many interceptions of slugs are made by quarantine inspectors (Robinson 1999), including species not yet found in the United States or restricted to areas of North America other than Florida. In addition to the many potential invasive slugs originating in temperate climates such as Europe, the traditional source of invasive molluscs for the US, Florida is also quite susceptible to invasion by slugs from warmer climates. Indeed, most of the invaders that have established here are warm-weather or tropical species. Following is a discus- sion of the situation in Florida, including problems with Figure 1. Lateral view of slug showing the breathing pore (pneumostome) open. When closed, the pore can be difficult to locate. slug identification and taxonomy, as well as the behavior, Note that there are two pairs of tentacles, with the larger, upper pair ecology, and management of slugs. bearing visual organs. Credits: Lyle J. Buss, UF/IFAS Biology as nocturnal activity and dwelling mostly in sheltered Slugs are snails without a visible shell (some have an environments. Slugs also reduce water loss by opening their internal shell and a few have a greatly reduced external breathing pore (pneumostome) only periodically instead of shell). The slug life-form (with a reduced or invisible shell) having it open continuously. Slugs produce mucus (slime), has evolved a number of times in different snail families, which allows them to adhere to the substrate and provides but this shell-free body form has imparted similar behavior some protection against abrasion, but some mucus also and physiology in all species of slugs. -

Slugs (Of Florida) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1

Archival copy: for current recommendations see http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu or your local extension office. EENY-087 Slugs (of Florida) (Gastropoda: Pulmonata)1 Lionel A. Stange and Jane E. Deisler2 Introduction washed under running water to remove excess mucus before placing in preservative. Notes on the color of Florida has a depauparate slug fauna, having the mucus secreted by the living slug would be only three native species which belong to three helpful in identification. different families. Eleven species of exotic slugs have been intercepted by USDA and DPI quarantine Biology inspectors, but only one is known to be established. Some of these, such as the gray garden slug Slugs are hermaphroditic, but often the sperm (Deroceras reticulatum Müller), spotted garden slug and ova in the gonads mature at different times (Limax maximus L.), and tawny garden slug (Limax (leading to male and female phases). Slugs flavus L.), are very destructive garden and greenhouse commonly cross fertilize and may have elaborate pests. Therefore, constant vigilance is needed to courtship dances (Karlin and Bacon 1961). They lay prevent their establishment. Some veronicellid slugs gelatinous eggs in clusters that usually average 20 to are becoming more widely distributed (Dundee 30 on the soil in concealed and moist locations. Eggs 1977). The Brazilian Veronicella ameghini are round to oval, usually colorless, and sometimes (Gambetta) has been found at several Florida have irregular rows of calcium particles which are localities (Dundee 1974). This velvety black slug absorbed by the embryo to form the internal shell should be looked for under boards and debris in (Karlin and Naegele 1958). -

Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Milacidae) from the Island of Bra Č (Dalmatia, Croatia)

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 The journal is available on line at www.ecol-mne.com http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A6EF195D-2F65-49F8-B5C6-CCFF9ED23E3E Tandonia bolensis n. sp., a new slug (Gastropoda: Pulmonata: Milacidae) from the island of Bra č (Dalmatia, Croatia) WILLY DE MATTIA 1* & GIANBATTISTA NARDI 2 1 International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (ICGEB) Padriciano, 99. 34149 Trieste, Italy, E- mail: [email protected].* Corresponding author. 2 Via Boschette 8/A, I-25064 Gussago (BS), Italy, E-mail: [email protected] Received 11 September 2014 │ Accepted 24 September 2014 │ Published online 25 September 2014. Abstract The genus Tandonia Lessona & Pollonera, 1882 is represented along the Western Balkans by about 13 taxa, most of which are regional endemics. Recent collecting on the island of Bra č (Croatia) has provided a single, fully grown specimen of a totally black slug. A careful investigation of the genital anatomy and body traits, reveal characteristic and unique morphological features which until now have never been observed in other representatives of the genus. Such results have led to the description of new species. Tandonia bolensis n. sp. is easily distinguishable by virtue of its genital features, the dummy-like penial-atrial papilla, and the long and partially spiral-convoluted, thorny spermatophore. Key words : Tandonia bolensis n. sp., Milacidae, Bra č island, Dalmatia, taxonomy, systematics, biogeography, Western Balkans, Mollusca. Introduction The slug family Milacidae Ellis, 1926 is represented by two genera: Milax Gray, 1855, with about 12 known species and Tandonia Lessona & Pollonera, 1882, with more than 30 species currently considered valid. -

Distribution and Population Dynamics of the Kerry Slug, Geomalacus Maculosus (Arionidae)

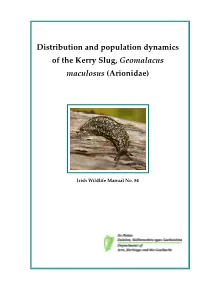

Distribution and population dynamics of the Kerry Slug, Geomalacus maculosus (Arionidae) Irish Wildlife Manual No. 54 Distribution and population dynamics of the Kerry Slug, Geomalacus maculosus (Arionidae) Rory Mc Donnell & Mike Gormally Applied Ecology Unit, Centre for Environmental Science, School of Natural Sciences, NUI Galway, Ireland. Citation: Mc Donnell, R.J. and Gormally, M.J. (2011). Distribution and population dynamics of the Kerry Slug, Geomalacus maculosus (Arionidae). Irish Wildlife Manual s, No. 54. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht, Dublin, Ireland. Cover photo: Geomalacus maculosus © Rory Mc Donnell The NPWS Project Officer for this report was: Dr Brian Nelson; [email protected] Irish Wildlife Manuals Series Editor: F. Marnell & N. Kingston © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2011 ISSN 1393 – 6670 Distribution and population dynamics of Geomalacus maculosus ____________________________________________________ CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...............................................................................................................................2 1. INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................3 Background information on Geomalacus maculosus .......................................................................3 -

Snail and Slug Dissection Tutorial: Many Terrestrial Gastropods Cannot Be

IDENTIFICATION OF AGRICULTURALLY IMPORTANT MOLLUSCS TO THE U.S. AND OBSERVATIONS ON SELECT FLORIDA SPECIES By JODI WHITE-MCLEAN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2012 1 © 2012 Jodi White-McLean 2 To my wonderful husband Steve whose love and support helped me to complete this work. I also dedicate this work to my beautiful daughter Sidni who remains the sunshine in my life. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my committee chairman, Dr. John Capinera for his endless support and guidance. His invaluable effort to encourage critical thinking is greatly appreciated. I would also like to thank my supervisory committee (Dr. Amanda Hodges, Dr. Catharine Mannion, Dr. Gustav Paulay and John Slapcinsky) for their guidance in completing this work. I would like to thank Terrence Walters, Matthew Trice and Amanda Redford form the United States Department of Agriculture - Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service - Plant Protection and Quarantine (USDA-APHIS-PPQ) for providing me with financial and technical assistance. This degree would not have been possible without their help. I also would like to thank John Slapcinsky and the staff as the Florida Museum of Natural History for making their collections and services available and accessible. I also would like to thank Dr. Jennifer Gillett-Kaufman for her assistance in the collection of the fungi used in this dissertation. I am truly grateful for the time that both Dr. Gillett-Kaufman and Dr. -

Occurrence of the Invasive Spanish Slug in Gardens

Dörler et al. BMC Ecol (2018) 18:23 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12898-018-0179-7 BMC Ecology RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Occurrence of the invasive Spanish slug in gardens: can a citizen science approach help deciphering underlying factors? Daniel Dörler1* , Matthias Kropf2, Gregor Laaha3 and Johann G. Zaller1 Abstract Background: The Spanish slug (Arion vulgaris, also known as A. lusitanicus) is considered one of the most invasive species in agriculture, horticulture and private gardens all over Europe. Although this slug has been problematic for decades, there is still not much known about its occurrence across private gardens and the underlying meteorological and ecological factors. One reason for this knowledge gap is the limited access of researchers to private gardens. Here we used a citizen science approach to overcome this obstacle and examined whether the occurrence of Arionidae in Austrian gardens was associated with meteorological (air temperature, precipitation, global solar radiation, relative humidity) or ecological factors (plant diversity, earthworm activity). Occurrence of the invasive A. vulgaris versus the similar-looking native A. rufus was compared using a DNA-barcoding approach. Results: Slugs were collected from 1061 gardens from the dry Pannonian lowland to the wet alpine climate (altitu- dinal range 742 m). Slug abundance in gardens was best explained and negatively associated with the parameters “sum of the mean air temperature in spring”, “number of frost days in the previous winter” and “mean daily global solar radiation on the day of data collection”. Precipitation, plant diversity and earthworm activity were also related to slug abundance, but positively. Out of our genetic sampling of collected slugs, 92% belonged to A. -

Community Horticulture Fact Sheet # 92 Slugs Few Northwest Gardeners

Community Horticulture Fact Sheet # 92 Slugs Few Northwest gardeners have escaped the fleshy lobe just behind the head. They reach 5 damage done by those gluttonous garden to 6 inches, but when resting or under attack, inhabitants, slugs. They can quickly devour European black slugs curl into a ball. newly planted marigolds and lettuce. Ideal living conditions make Western Washington a •Great Gray Garden Slug - Limax maximus. veritable slug paradise. Our wet climate Native to Europe and Asia Minor, gray garden provides slugs with the moisture they need to slugs have a spotted or striped mantle. They survive and an abundance of plants to eat. are about 4 inches long, but can move four Combine this with the slug’s ability to times faster than a banana slug. These reproduce in large numbers, and it’s a wonder cannibalistic slugs are a serious threat to the we aren’t ankle deep in slug slime! native banana slugs. Slugs are soft-bodied animals without a •Milky Slug - Deroceras reticulatum. Imported backbone. Their heads contain a from northern Europe and Asia, milky slugs get concentration of nerve cells and sport tentacles their name from the milky slime they produce, tipped by small, light-sensitive eyes. Slugs especially when irritated. About 2 inches long, move on a muscular foot over a mucous trail they are usually light brown or gray with darker (slime) which is secreted by a gland beneath mottling. The concentric folds on the mantle the head. They can live from one to six years and a ridge running down the back help identify and can lay 500 eggs per year. -

Slugs: a Guide to the Invasive and Native Fauna of California ANR Publication 8336 2

University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources http://anrcatalog.ucdavis.edu Publication 8336 • January 2009 SLUGA Guide to the InvasiveS and Native Fauna of California RORY J. MC DONNELL, Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside; TimOTHY D. PAINE, Department of Entomology, University of California, Riverside; and MICHAEL J. GOrmALLY, Applied Ecology Unit, Centre for Environmental Science, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland Introduction Slugs have long been regarded worldwide as severe pests of agricultural and horticultural production, attacking a vast array of crops (reviewed by South [1992] and Godan [1983]). Species such as Deroceras reticulatum (Müller1), Arion hortensis d’Audebard de Férussac, and Tandonia budapestensis (Hazay) are among the most pestiferous (South 1992) and have increased their ranges as humans have continued their colonization of the planet. Slugs have also been implicated in the transmission of many plant pathogens, such as Alternaria brassicicola Schw., the causal agent of brassica dark leaf spot (Hasan and Vago 1966). In addition, they have been implicated as vectors of Angiostrongylus cantonensis (Chen), which can cause the potentially lethal eosinophilic meningo-encephalitis in humans (Aguiar, Morera, and Pascual 1981; Lindo et al. 2004) and Angiostrongylus costaricensis Morera and Céspedes, which causes abdominal angiostrongyliasis (South 1992). Recent evidence also indicates that slugs vector Campylobacter spp. and Escherichia coli (Migula), which cause food poisoning and may have been partially responsible for recent, highly publicized massive recalls of contaminated spinach and other salad crops grown in California (Raloff 2007, Sproston et al. 2006). 1Slug taxonomy follows Anderson (2005) throughout. Slugs: A Guide to the Invasive and Native Fauna of California ANR Publication 8336 2 In California, slugs and humans have had a long of Natural Sciences, 1900 Ben Franklin Parkway, history. -

Identifying British Slugs

Identifying British Slugs Brian Eversham version 1.0 October 2012 This is an updated version of a guide I produced in 1988. It aims to provide a quick and simple key to identify all British slugs to species level. It uses external features, most easily seen on live slugs. It should allow accurate identification of all but four pairs or trios of very closely related species, whose identity is best confirmed by dissection. Even these can be tentatively named without dissection. The key is a revision and expansion of those included in Eversham & Jackson (1982) and the Aidgap key (Cameron, Eversham & Jackson, 1983), and it has been extended to include recent additions to the British list. The illustrations are original, except for the genitalia figures of Milax nigricans (after Quick, 1952), and the figures of the Arion hortensis group (adapted from Davies (1977, 1979), Backeljau (1986) and Anderson (2004)), and Arion fuscus (XXXX). Useful identification features The following photographs shows the main features used in the keys. Body Tail Mantle Head Tubercles Breathing Tentacle Foot-fringe pore The above, Lusitanian Slug, Arion vulgaris, is a large round-back slug, which does not have a keel down its back, and does not have either a groove or a finger-print-like set of concentric ridges on its mantle: the next illustrations show those features. Like most large Arion species, it has a mucus gland at the tail tip, above the foot-fringe, which often has a small blob of slime attached. The breathing pore is conspicuous when open, but hard to see when closed.