China's Financial System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interim Report 2018

Stock Code: 6098 碧桂園服務控股有限公司 碧桂園服務控股有限公司 Country Garden Services Holdings Company Limited Country Garden Services Holdings Company Limited Services Company Holdings Garden Country (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) 2018 INTERIM REPORT 2018 INTERIM REPORT Contents 2 Corporate Information 3 Awards and Honours 4 Chairman’s Statement 6 Management Discussion and Analysis 20 Corporate Governance and Other Information 22 Interests Disclosure 25 Interim Condensed Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 26 Interim Condensed Consolidated Balance Sheet 28 Interim Condensed Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 29 Interim Condensed Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 30 Notes to the Interim Financial Information CORPORATE INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS CAYMAN ISLANDS PRINCIPAL SHARE REGISTRAR Executive Directors AND TRANSFER OFFICE Mr. Li Changjiang Conyers Trust Company (Cayman) Limited Mr. Xiao Hua Cricket Square, Hutchins Drive Mr. Guo Zhanjun P.O. Box 2681 Grand Cayman Non-executive Directors KY1-1111 Ms. Yang Huiyan (Chairman) Cayman Islands Mr. Yang Zhicheng HONG KONG BRANCH SHARE REGISTRAR Ms. Wu Bijun Tricor Investor Services Limited Level 22, Hopewell Centre Independent Non-executive Directors 183 Queen’s Road East, Hong Kong Mr. Mei Wenjue Mr. Rui Meng AUDITORS Mr. Chen Weiru PricewaterhouseCoopers Certifi ed Public Accountants AUDIT COMMITTEE 22nd Floor, Prince’s Building, Central, Hong Kong Mr. Rui Meng (Chairman) Mr. Mei Wenjue COMPLIANCE ADVISOR Mr. Chen Weiru Somerley Capital Limited 20/F, China Building, 29 Queen’s Road Central, REMUNERATION COMMITTEE Central, Hong Kong Mr. Chen Weiru (Chairman) Ms. Yang Huiyan LEGAL ADVISERS Mr. Mei Wenjue As to Hong Kong laws: Woo Kwan Lee & Lo NOMINATION COMMITTEE 26/F, Jardine House. -

Regulatory Responses to the Chinese Shadow Banking Development

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Portal Czasopism Naukowych (E-Journals) Jagiellonian Journal of Management vol. 1 (2015), no. 4, pp. 305–317 doi:10.4467/2450114XJJM.15.021.4830 www.ejournals.eu/jjm Regulatory responses to the Chinese shadow banking development Piotr Łasak1 The Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Institute of Economics, Finance and Management Abstract Shadow banking systems were developing rapidly in the Western economies during the last two decades. Research from recent years show that within the last years equally important process of shadow banking development occurs in some emerging markets, and among oth- ers, in China. The system was not only a sophisticated part of China’s financial market, but played very important role in the development of the Chinese economy. The aim of this arti- cle is a description of the mechanisms of shadow banking development in China, character- istics of the main threats of this system and the regulatory approach in the country. Despite many threats, the shadow banking system plays an important role in the Chinese econo- my. There is a need for its regulation and support for further development. Paper type: review article Keywords: Chinese financial market, shadow banking, trust companies, wealth manage- ment products Introduction Shadow banking is evolving mainly in developed countries. The Financial Stabili- ty Board estimates that in 2014 more than 80% of global shadow banking assets re- side in advanced economies (FSB Financial Stability Board, 2015, p. 2). Despite that there are several countries classified as an emerging economy or developing coun- try, where the system is growing very rapidly. -

The Public Banks and People's Bank of China: Confronting

Chapter 13 Godfrey Yeung THE PUBLIC BANKS AND PEOPLE’S BANK OF CHINA: CONFRONTING COVID-19 (IF NOT WITHOUT CONTROVERSY) he outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan and its subsequent dom- ino effects due to the lock-down in major cities have had a devastating effect on the Chinese economy. China is an Tinteresting case to illustrate what policy instruments the central bank can deploy through state-owned commercial banks (a form of ‘hybrid’ public banks) to buffer the economic shock during times of crisis. In addition to the standardized practice of liquidity injection into the banking system to maintain its financial viability, the Chi- nese central bank issued two top-down and explicit administra- tive directives to state-owned commercial banks: the minimum quota on lending to small- and medium-sized enterprises (MSEs) and non-profitable lending. Notwithstanding its controversy on loopholes related to such lending practices, these pro-active policy directives provide counter-cyclical lending and appear able to pro- vide short-term relief for SMEs from the Covid-19 shock in a timely manner. This has helped to mitigate the devastating impacts of the pandemic on the Chinese economy. 283 Godfrey Yeung INTRODUCTION The outbreak of Covid-19 leading to the lock-down in Wuhan on January 23, 2020 and the subsequent pandemic had significant im- pacts on the Chinese economy. China’s policy response regarding the banking system has helped to mitigate the devastating impacts of pandemic on the Chinese economy. Before we review the measures implemented by the Chinese gov- ernment, it is important for us to give a brief overview of the roles of two major group of actors (institutions) in the banking system. -

China Construction Bank 2018 Reduced U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section

China Construction Bank 2018 Reduced U.S. Resolution Plan Public Section 1 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Overview of China Construction Bank Corporation ...................................................................................... 3 1. Material Entities .................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Core Business Lines ............................................................................................................................... 4 3. Financial Information Regarding Assets, Liabilities, Capital and Major Funding Sources .................... 5 3.1 Balance Sheet Information ........................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Major Funding Sources ................................................................................................................. 8 3.3 Capital ........................................................................................................................................... 8 4. Derivatives Activities and Hedging Activities ........................................................................................ 8 5. Memberships in Material Payment, Clearing and Settlement Systems ............................................... 8 6. Description of Foreign Operations ....................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 1 Corporate Overview

ai161915073836_Yida AR20 Cover_21.5mm_output.pdf 1 23/4/2021 下午12:05 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Contents Corporate Overview 2 Corporate Information 3 Financial Summary 5 Chairman’s Statement 7 Management Discussion and Analysis 11 Environmental, Social and Governance Report 39 Profile of Directors and Senior Management 60 Directors’ Report 65 Corporate Governance Report 80 Independent Auditor’s Report 90 Consolidated Financial Statements • Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss 97 • Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income 98 • Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 99 • Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 101 • Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows 103 • Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 105 Yida China Holdings Limited 2020 Annual Report 1 Corporate Overview Yida China Holdings Limited (the “Company”), together with its industrial upgrading strategies, fully integrated internal and external subsidiaries (collectively referred to as the “Group”), founded in resources, further developed and operated Dalian Ascendas IT Park, 1988, headquartered in Shanghai, is China’s largest business park Tianjin Binhai Service Outsourcing Industrial Park, Suzhou High- developer and leading business park operator. The main business tech Software Park, Wuhan Guanggu Software Park, Dalian Tiandi, involves business park development and operation, residential Dalian BEST City, Wuhan Software New Town, Yida Information properties within and outside business parks and office properties Software Park and many other software parks and technology sales, business park entrusted operation and management and parks. It helped the Group achieve its preliminary strategic goals of construction, decoration and landscaping services. On 27 June “National Expansion, Business Model Exploration and Diversified 2014, the Company was successfully listed (the “Listing”) on the Cooperation”. -

Announcement Report for the First Quarter of 2021 Of

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. ANNOUNCEMENT REPORT FOR THE FIRST QUARTER OF 2021 OF CHINA CITIC BANK CORPORATION LIMITED This announcement is made by CITIC Limited (the “Company”) pursuant to Rule 13.09(2)(a) of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Inside Information Provisions under Part XIVA of the Securities and Futures Ordinance (Chapter 571 of the Laws of Hong Kong). The Company notes the announcement (the “CITIC Bank Announcement”) of today’s date made by China CITIC Bank Corporation Limited (“CITIC Bank”), a principal subsidiary of the Company, in relation to the unaudited consolidated results of CITIC Bank and its subsidiaries for the first quarter ended 31 March 2021. The CITIC Bank Announcement is available on the website of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited at www.hkexnews.hk and is set out at the end of this announcement. By Order of the Board CITIC Limited Zhu Hexin Chairman Hong Kong, 29 April 2021 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr Zhu Hexin (Chairman), Mr Xi Guohua and Ms Li Qingping; the non-executive directors of the Company are Mr Song Kangle, Mr Liu Zhuyu, Mr Peng Yanxiang, Ms Yu Yang, Mr Liu Zhongyuan and Mr Yang Xiaoping; and the independent non-executive directors of the Company are Mr Francis Siu Wai Keung, Dr Xu Jinwu, Mr Anthony Francis Neoh, Mr Shohei Harada and Mr Gregory Lynn Curl. -

International Rating Agency Advisory Newsletter November 2012 Update Welcome to Aon Benfield’S Updated Rating Agency Advisory Newsletter

International Rating Agency Advisory Newsletter November 2012 Update Welcome to Aon Benfield’s updated Rating Agency Advisory Newsletter. In this edition, matters of interest include rating agencies global reinsurance and country risk outlooks, as well as our regular features on : Selected regulatory activities or updates throughout APAC and EMEA. List of rating actions in APAC and EMEA during the 3rd quarter. Links to reports released by Aon Benfield Analytics. We will continuously scan for new content to provide greater value to our clients. We will be glad to hear your feedback so that we can continue to provide the most relevant ratings news and information in future editions. Rating Agency Activity (Data source: Standard & Poor’s, A.M.Best, Fitch, and Moody’s) Standard & Poor’s Numerous market participants provided feedback on S&P’s proposed criteria for rating insurers, “Request for Comment: Insurers Rating Methodology”, published 9 July 2012. S&P has stated in its recent report “S&P Summarizes Submissions On Request For Comments” on 18 October 2012 that it received formal feedback from about 100 market participants, varying from rated insurers, insurance brokers, rating advisors, and industry trade associations. S&P is not yet in a position to comment on the final criteria. However S&P expects to respond to the comments in one of three ways: by changing the proposed criteria, by explaining the original proposals more clearly to remove ambiguity, or by leaving the proposal unchanged. S&P states that it is in the process of analyzing the feedback and testing the impact of various alternatives. -

中 國 民 生 銀 行 股 份 有 限 公 司 China Minsheng Banking Corp., Ltd

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中國民生銀行股份有限公司 CHINA MINSHENG BANKING CORP., LTD. (A joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 01988) (USD Preference Shares Stock Code: 04609) Results Announcement For the Year Ended 31 December 2019 The Board of Directors (the “Board”) of China Minsheng Banking Corp., Ltd. (the “Company”) hereby announces the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Hong Kong Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of annual results. Publication of Annual Results Announcement and Annual Report This results announcement will be published on the HKEXnews website of Hong Kong Stock Exchange (www.hkexnews.hk) and the Company’s website (www.cmbc.com.cn). The 2019 Annual Report of the Company will be dispatched to holders of H shares of the Company and published on the websites of the Company and Hong Kong Stock Exchange in due course. Profit Distribution On 30 March 2020, the 20th meeting of the seventh session of the Board of the Company approved the profit distribution plan to declare to holders of A shares and H shares whose names appear on the registers as at the record dates as indicated in the notice of 2019 annual general meeting of the Company to be published by the Company in due course, a cash dividend of RMB3.70 (tax inclusive) for every 10 shares being held. -

Tencent (700 HK)

BOCOM Int’l Research Company Update Internet Last Close Target Price Upside 17 May 2018 HK$396.2 HK$533.00↓ +35% Tencent (700 HK) Solid top-line growth in 1Q18 Revenue beat on payment; profit in line: Total revenue/non-GAAP net profit rose Stock Rating 48%/29% YoY in 1Q18. Revenue was 4% higher than consensus driven by solid BUY performance of payment-related services (triple-digit growth YoY). GPM for VAS was up 4ppts/2ppts QoQ/YoY driven by higher revenue contribution from in-house 1-year stock performance games. GPM of cloud and payment improved to 25.4% (up 3ppts QoQ/YoY). Non- GAAP net margin was 25%, compared with 26%/29% in 4Q17/1Q17. 100% HSI 700 HK 80% Segment review: PC game/mobile game revenue were in line with our expectation, 60% 40% at RMB14.1bn/21.7bn, up 0%/68% YoY. Revenue from DnF reached a record high 20% thanks to seasonal promotion, while total PC game revenue remained flattish YoY. 0% -20% Mobile game revenue was strong, led by HoK, CF, and newly launched MU May-17 Sep-17 Jan-18 May-18 Awakening and QQ Speed, primarily driven by 42% YoY growth of ARPU. Social ads Source: Bloomberg revenue surged 69% YoY to RMB7.4bn, supported by increased ad load from WeChat Moments and higher CPC for mobile ad network. Tencent Video posted Stock data 52w high (HK$) 476.60 sound performance with subscription/ad revenue up 85%/64% YoY. 52w low (HK$) 256.2 Market cap (HK$ m) 3,765,361 Strategic development: Mini Games was also encouraging with 500+ games Avg daily vol (m) 25.75 launched and over 1/3 of players being brand-new gamers of Tencent. -

中國中車股份有限公司 Crrc Corporation Limited

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. 中 國 中 車 股 份 有 限 公 司 CRRC CORPORATION LIMITED (a joint stock limited company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 1766) US$600,000,000 Zero Coupon Convertible Bonds due 2021 Stock code: 5613 2018 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors of CRRC Corporation Limited (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the unaudited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the six months ended 30 June 2018. This announcement, containing the main text of the 2018 interim report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (the “Stock Exchange”) in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcements of interim results. The 2018 interim report of the Company and its printed version will be published and delivered to the H shareholders of the Company and available for view on the websites of the Stock Exchange at http://www.hkex.com.hk and of the Company at http://www.crrcgc.cc on or before 30 September 2018. By order of the Board CRRC Corporation Limited Liu Hualong Chairman Beijing, the PRC 24 August 2018 As at the date of this announcement, the executive directors of the Company are Mr. -

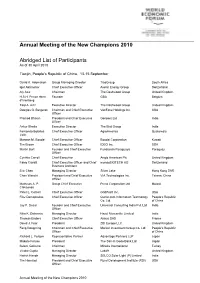

Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2010 Abridged List Of

Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2010 Abridged List of Participants As of 30 April 2010 Tianjin, People's Republic of China, 13-15 September David K. Adomakoh Group Managing Director TisoGroup South Africa Igor Akhmerov Chief Executive Officer Avelar Energy Group Switzerland Aly Aziz Chairman The Dashwood Group United Kingdom H.S.H. Prince Henri Founder GBA Belgium d'Arenberg Taqi A. Aziz Executive Director The Dashwood Group United Kingdom Douglas G. Bergeron Chairman and Chief Executive VeriFone Holdings Inc. USA Officer Pramod Bhasin President and Chief Executive Genpact Ltd India Officer Ankur Bhatia Executive Director The Bird Group India Fernando Bolaños Chief Executive Officer AgroAmerica Guatemala Valle Marwan M. Boodai Chief Executive Officer Boodai Corporation Kuwait Tim Brown Chief Executive Officer IDEO Inc. USA Martin Burt Founder and Chief Executive Fundación Paraguaya Paraguay Officer Cynthia Carroll Chief Executive Anglo American Plc United Kingdom Fabio Cavalli Chief Executive Officer and Chief mondoBIOTECH AG Switzerland Business Architect Eric Chen Managing Director Silver Lake Hong Kong SAR Chen Wenchi President and Chief Executive VIA Technologies Inc. Taiwan, China Officer Mathews A. P. Group Chief Executive Press Corporation Ltd Malawi Chikaonda Peter L. Corsell Chief Executive Officer GridPoint Inc. USA Fritz Demopoulos Chief Executive Officer Qunar.com Information Technology People's Republic Co. Ltd. of China Jay P. Desai Founder and Chief Executive Universal Consulting India Pvt. Ltd India Officer Nitin K. Didwania Managing Director Hazel Mercantile Limited India Thomas Enders Chief Executive Officer Airbus SAS France David J. Fear President ZBI Europe LLC United Kingdom Feng Dongming Chairman and Chief Executive Markor Investment Group Co. -

Circular of the Beijing Municipal Finance Bureau on Strengthening Financial Services to Support the Prevention and Control of the COVID-19 Epidemic 56

For Foreign-invested Enterprises in Beijing Municipality Compilation of Support Policies for Enterprises in Beijing Municipality During the COVID-19 Epidemic Beijing Municipal Commerce Bureau Contents Circular of the General Office of the Ministry of Commerce on Proactively Responding to the COVID-19 Epidemic, Strengthening Services for Foreign-invested Enterprises and Enhancing Investment Promotion 5 Circular of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality on Releasing the Measures for Further Supporting Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises to Mitigate the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic and Maintain Stable Development 8 Measures for Further Supporting Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises to Mitigate the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic and Maintain Stable Development 9 Circular of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality on Issuing the Measures for Preventing and Controlling the COVID-19 Epidemic and Ensuring the Safe and Orderly Resumption of Work and Production by Enterprises 14 Measures for Preventing and Controlling the COVID-19 Epidemic and Ensuring the Safe and Orderly Resumption of Work and Production by Enterprises 14 Measures of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality for Further Supporting the Efforts to Defeat the COVID-19 Epidemic 19 Measures of the General Office of the People's Government of Beijing Municipality for Mitigating the Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic, and Supporting Sustained and Healthy Development of Micro, Small