Motion of Admonishment and Censure of Wallace L. Hall Jr. And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE

UNITED STATES Proxy Voting Guidelines Benchmark Policy Recommendations TITLE Effective for Meetings on or after February 1, 2021 Published November 19, 2020 ISS GOVERNANCE .COM © 2020 | Institutional Shareholder Services and/or its affiliates UNITED STATES PROXY VOTING GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Coverage ................................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Board of Directors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Voting on Director Nominees in Uncontested Elections ........................................................................................... 8 Independence ....................................................................................................................................................... 8 ISS Classification of Directors – U.S. ................................................................................................................. 9 Composition ........................................................................................................................................................ 11 Responsiveness ................................................................................................................................................... 12 Accountability .................................................................................................................................................... -

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History

Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Updated February 1, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45087 Resolutions to Censure the President: Procedure and History Summary Censure is a reprimand adopted by one or both chambers of Congress against a Member of Congress, President, federal judge, or other government official. While Member censure is a disciplinary measure that is sanctioned by the Constitution (Article 1, Section 5), non-Member censure is not. Rather, it is a formal expression or “sense of” one or both houses of Congress. Censure resolutions targeting non-Members have utilized a range of statements to highlight conduct deemed by the resolutions’ sponsors to be inappropriate or unauthorized. Before the Nixon Administration, such resolutions included variations of the words or phrases unconstitutional, usurpation, reproof, and abuse of power. Beginning in 1972, the most clearly “censorious” resolutions have contained the word censure in the text. Resolutions attempting to censure the President are usually simple resolutions. These resolutions are not privileged for consideration in the House or Senate. They are, instead, considered under the regular parliamentary mechanisms used to process “sense of” legislation. Since 1800, Members of the House and Senate have introduced resolutions of censure against at least 12 sitting Presidents. Two additional Presidents received criticism via alternative means (a House committee report and an amendment to a resolution). The clearest instance of a successful presidential censure is Andrew Jackson. The Senate approved a resolution of censure in 1834. On three other occasions, critical resolutions were adopted, but their final language, as amended, obscured the original intention to censure the President. -

Ways and Means Committee's Request for the Former President's

(Slip Opinion) Ways and Means Committee’s Request for the Former President’s Tax Returns and Related Tax Information Pursuant to 26 U.S.C. § 6103(f )(1) Section 6103(f )(1) of title 26, U.S. Code, vests the congressional tax committees with a broad right to receive tax information from the Department of the Treasury. It embod- ies a long-standing judgment of the political branches that the tax committees are uniquely suited to receive such information. The committees, however, cannot compel the Executive Branch to disclose such information without satisfying the constitutional requirement that the information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose. In assessing whether requested information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose, the Executive Branch must give due weight to Congress’s status as a co-equal branch of government. Like courts, therefore, Executive Branch officials must apply a pre- sumption that Legislative Branch officials act in good faith and in furtherance of legit- imate objectives. When one of the congressional tax committees requests tax information pursuant to section 6103(f )(1), and has invoked facially valid reasons for its request, the Executive Branch should conclude that the request lacks a legitimate legislative purpose only in exceptional circumstances. The Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee has invoked sufficient reasons for requesting the former President’s tax information. Under section 6103(f )(1), Treasury must furnish the information to the Committee. July 30, 2021 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING GENERAL COUNSEL DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY The Internal Revenue Code requires the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) and the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) to keep tax returns and related information confidential, 26 U.S.C. -

Committee Handbook New Mexico Legislature

COMMITTEE HANDBOOK for the NEW MEXICO LEGISLATURE New Mexico Legislative Council Service Santa Fe, New Mexico 2012 REVISION prepared by: The New Mexico Legislative Council Service 411 State Capitol Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 (505) 986-4600 www.nmlegis.gov 202.190198 PREFACE Someone once defined a committee as a collection of people who individually believe that something must be done and who collectively decide that nothing can be done. Whether or not this definition has merit, it is difficult to imagine the work of a legislative body being accomplished without reliance upon the committee system. Every session, American legislative bodies are faced with thousands of bills, resolutions and memorials upon which to act. Meaningful deliberation on each of these measures by the entire legislative body is not possible. Therefore, the job must be broken up and distributed among the "miniature legislatures" called standing or substantive committees. In New Mexico, where the constitution confines legislative action to a specified number of calendar days, the work of such committees assumes even greater importance. Because the role of committees is vital to the legislative process, it is necessary for their efficient operation that individual members of the senate and house and their staffs understand committee functioning and procedure, as well as their own roles on the committees. For this reason, the legislative council service published in 1963 the first Committee Handbook for New Mexico legislators. This publication is the sixth revision of that document. i The Committee Handbook is intended to be used as a guide and working tool for committee chairs, vice chairs, members and staff. -

Simplified Parliamentary Procedure

Extension to Communities Simplifi ed Parliamentary Procedure 2 • Iowa State University Extension Introduction Effective Meetings — Simplifi ed Parliamentary Procedure “We must learn to run a meeting without victimizing the audience; but more impor- tantly, without being victimized by individuals who are armed with parliamentary procedure and a personal agenda.” — www.calweb.com/~laredo/parlproc.htm Parliamentary procedure. Sound complicated? Controlling? Boring? Intimidating? Why do we need to know all those rules for conducting a meeting? Why can’t we just run the meetings however we want to? Who cares if we follow parliamentary procedure? How many times have you attended a meeting that ran on and on and didn’t accomplish anything? The meeting jumps from one topic to another without deciding on anything. Group members disrupt the meeting with their own personal agendas. Arguments erupt. A few people make all the decisions and ignore everyone else’s opinions. Everyone leaves the meeting feeling frustrated. Sound familiar? Then a little parliamentary procedure may just be the thing to turn your unproductive, frustrating meetings into a thing of beauty — or at least make them more enjoyable and productive. What is Parliamentary Procedure? Parliamentary procedure is a set of well proven rules designed to move business along in a meeting while maintaining order and controlling the communications process. Its purpose is to help groups accomplish their tasks through an orderly, democratic process. Parliamentary procedure is not intended to inhibit a meeting with unnecessary rules or to prevent people from expressing their opinions. It is intended to facilitate the smooth func- tioning of the meeting and promote cooperation and harmony among members. -

BRNOVICH V. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus BRNOVICH, ATTORNEY GENERAL OF ARIZONA, ET AL. v. DEMOCRATIC NATIONAL COMMITTEE ET AL. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT No. 19–1257. Argued March 2, 2021—Decided July 1, 2021* Arizona law generally makes it very easy to vote. Voters may cast their ballots on election day in person at a traditional precinct or a “voting center” in their county of residence. Ariz. Rev. Stat. §16–411(B)(4). Arizonans also may cast an “early ballot” by mail up to 27 days before an election, §§16–541, 16–542(C), and they also may vote in person at an early voting location in each county, §§16–542(A), (E). These cases involve challenges under §2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) to aspects of the State’s regulations governing precinct-based election- day voting and early mail-in voting. First, Arizonans who vote in per- son on election day in a county that uses the precinct system must vote in the precinct to which they are assigned based on their address. See §16–122; see also §16–135. -

Steering Committee Ground Rules

The Humboldt Operational Area Hazard Mitigation Plan STEERING COMMITTEE GROUND RULES PURPOSE As the title suggests, the role of the Steering Committee is to guide the Humboldt County Planning Partners through the process of updating the 2008 Humboldt Operational Area Hazard Mitigation Plan. This process will result in a plan that can be embraced both politically and by the constituency within the planning area. The Committee will provide guidance and leadership, oversee the planning process, and act as the point of contact for all partners and the various interest groups in the planning area. The makeup of this committee was selected to provide the best possible cross section of views to enhance the planning effort and to help build support for hazard mitigation. CHAIRPERSON The Steering Committee selected Jay Parrish, City Manager of the City of Ferndale to be chairperson. The role of a chair is to: 1) lead meetings so that agendas are followed and meetings adjourn on-time, 2) allow all members to be heard during discussions, 3) moderate discussions between members with differing points of view, 4) be a sounding board for staff in the preparation of agendas and how to best involve the full Committee in work plan tasks, 5) and to act as spokesperson during public involvement processes and public interchanges. Hank Seemann of County of Humboldt Public Works, was selected as vice chairperson to take the chair's role when the chair is not available. The Committee chose to adopt a rule that requires either the chair or the vice chair to be present at any given meeting. -

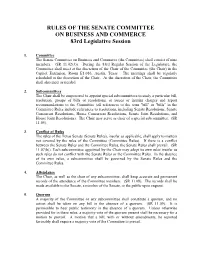

RULES of the SENATE COMMITTEE on BUSINESS and COMMERCE 83Rd Legislative Session

RULES OF THE SENATE COMMITTEE ON BUSINESS AND COMMERCE 83rd Legislative Session 1. Committee The Senate Committee on Business and Commerce (the Committee) shall consist of nine members. (SR 11.02(3)). During the 83rd Regular Session of the Legislature, the Committee shall meet at the discretion of the Chair of the Committee (the Chair) in the Capitol Extension, Room E1.016, Austin, Texas. The meetings shall be regularly scheduled at the discretion of the Chair. At the discretion of the Chair, the Committee shall also meet as needed. 2. Subcommittees The Chair shall be empowered to appoint special subcommittees to study a particular bill, resolution, groups of bills or resolutions, or issues or interim charges and report recommendations to the Committee (all references to the term "bill" or "bills" in the Committee Rules include references to resolutions, including Senate Resolutions, Senate Concurrent Resolutions, House Concurrent Resolutions, Senate Joint Resolutions, and House Joint Resolutions). The Chair may serve as chair of a special subcommittee. (SR 11.05). 3. Conflict of Rules The rules of the Texas Senate (Senate Rules), insofar as applicable, shall apply to matters not covered by the rules of the Committee (Committee Rules). If there is a conflict between the Senate Rules and the Committee Rules, the Senate Rules shall prevail. (SR 11.07(b)). Each subcommittee appointed by the Chair may adopt its own rules insofar as such rules do not conflict with the Senate Rules or the Committee Rules. In the absence of its own rules, a subcommittee shall be governed by the Senate Rules and the Committee Rules. -

Quorum ADM-BO-023

Policy/Procedure Title Policy Number Quorum ADM-BO-023 Developer Category Board Issue Date December 2014 Governance Committee Revision Date May 5, 2021 Next Review Date May 2024 Index 1.0 Scope of Policy/Procedure 2.0 Policy Statement 3.0 Procedure/Process 3.1 Protocol and Special Cases 3.2 Policy Oversight 4.0 Stakeholder Review 5.0 Approval 1.0 Scope of Policy/Procedure This policy is designed to support the Board of Directors in defining MEETING QUORUM, the minimum number of committee or Board members that must be present at a meeting in order to conduct business. If quorum is not reached then no motions may be passed at the meeting. Committee and Board Chairs need to be careful to ensure that quorum is reached for meetings. 2.0 Policy Statement As a general rule, the quorum for any committee or Board meeting is ‘50% of the voting members plus one. If the result is a fractional number, round down to get the quorum number’. Therefore, a committee with four (4) members with voting privileges (0.5 x 4) + 1 = 3 members present to have quorum. A committee with nine (9) members requires (0.5 x 9) + 1 = 5.5 rounded down to give five (5) members present to have quorum. 3.0 Procedure/Process 3.1 Protocol and Special Cases: It is the responsibility of the Board Chair or the Committee Chair to determine the exact number of VOTING members CURRENTLY on the Board or the Committee. Consult the Terms of Reference for the Committee for the exact list of voting and non-voting members. -

The Constitutionality of Legislative Supermajority Requirements: a Defense

The Constitutionality of Legislative Supermajority Requirements: A Defense John 0. McGinnist and Michael B. Rappaporttt INTRODUCTION On the first day of the 104th Congress, the House of Representatives adopted a rule that requires a three-fifths majority of those voting to pass an increase in income tax rates.' This three-fifths rule had been publicized during the 1994 congressional elections as part of the House Republicans' Contract with America. In a recent Open Letter to Congressman Gingrich, seventeen well-known law professors assert that the rule is unconstitutional.3 They argue that requiring a legislative supermajority to enact bills conflicts with the intent of the Framers. They also contend that the rule conflicts with the Constitution's text, because they believe that the Constitution's specific supermajority requirements, such as the requirement for approval of treaties, indicate that simple majority voting is required for the passage of ordinary legislation.4 t Professor of Law, Benjamin N. Cardozo Law School. tt Professor of Law, University of San Diego School of Law. The authors would like to thank Larry Alexander, Akhil Amar, Carl Auerbach, Jay Bybee, David Gray Carlson, Lawrence Cunningham, Neal Devins, John Harrison, Michael Herz, Arthur Jacobson, Gary Lawson, Nelson Lund, Erela Katz Rappaport, Paul Shupack, Stewart Sterk, Eugene Volokh, and Fred Zacharias for their comments and assistance. 1. See RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, EFFECTIVE FOR ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS (Jan. 4, 1995) [hereinafter RULES] (House Rule XXI(5)(c)); see also id. House Rule XXI(5)(d) (barring retroactive tax increases). 2. The rule publicized in the Contract with America was actually broader than the one the House enacted. -

§ 12. Expulsion, Exclusion, and Censure

Ch. 8 § 11 DESCHLER’S PRECEDENTS expenditures to the Clerk and in- As to exclusion—or denial by dicated his intention once in the House of the right of a Mem- Washington to complete and file ber-elect to a seat—by majority the required forms. vote, the House has the power to On June 2, 1936, the House de- judge elections and to determine clared the contestee entitled to his that no one was properly elected seat.(4) to a seat. If violations of the elec- tion campaign statutes are so ex- tensive or election returns so un- § 12. Expulsion, Exclusion, certain as to render an election void, the House may deny the and Censure right to a seat.(8) [Note: For full discussion of cen- sure and expulsion, see chapter 12, infra.] Expulsion Under article I, section 5, clause 2 of the United States Constitu- § 12.1 In the 77th Congress, the tion, the House may punish its Senate failed to expel, such Members and may expel a Mem- expulsion requiring a two- ber by a vote of two-thirds. thirds vote, a Senator whose In the 90th Congress, the Sen- qualifications had been chal- ate censured a Member in part for lenged by reason of election improper use and conversion of fraud and of conduct involv- campaign funds.(5) And the Com- mittee on House Administration ing moral turpitude. recommended in a report in the On Jan. 3, 1941, at the con- 74th Congress that a Member or vening of the 77th Congress, Mr. Delegate could be censured for William Langer, of North Dakota, failure to comply with the Corrupt took the oath of office, despite Practices Act.(6) However, the charges from the citizens of his House and the Senate have gen- state recommending he be denied erally held that a Member may a congressional seat because of not be expelled for conduct com- campaign fraud and past conduct mitted prior to his election.(7) involving moral turpitude.(9) 4. -

2021 Legislative Calendar

2021 TENTATIVE LEGISLATIVE CALENDAR COMPILED BY THE OFFICE OF THE ASSEMBLY CHIEF CLERK AND THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE SENATE Revised 12-18-20 DEADLINES JANUARY S M T W TH F S Jan. 1 Statutes take effect (Art. IV, Sec. 8(c)). 1 2 Jan. 10 Budget must be submitted by Governor (Art. IV, Sec. 12(a)). Wk. 1 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jan. 11 Legislature reconvenes (J.R. 51(a)(1)). Wk. 2 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Jan. 18 Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Wk. 3 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Jan. 22 Last day to submit bill requests to the Office of Legislative Counsel. Wk. 4 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Wk. 1 31 FEBRUARY S M T W TH F S Wk. 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wk. 2 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wk. 3 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Feb. 15 Presidents' Day. Feb. 19 Last day for bills to be introduced (J.R. 61(a)(1), J.R. 54(a)). Wk. 4 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Wk. 1 28 MARCH S M T W TH F S Wk. 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wk. 2 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wk. 3 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Wk. 4 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Mar. 25 Spring Recess begins upon adjournment (J.R. 51(a)(2)). Spring Mar. 31 Cesar Chavez Day observed. 28 29 30 31 Recess APRIL S M T W TH F S Spring Recess 1 2 3 Wk.