The History of the Honolulu Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievements and Adjustment: a Literature Review

RESEARCH The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievements and Adjustment: A Literature Review Professor Charles Desforges with Alberto Abouchaar Research Report RR433 Research Report No 433 THE IMPACT OF PARENTAL INVOLVEMENT, PARENTAL SUPPORT AND FAMILY EDUCATION ON PUPIL ACHIEVEMENT AND ADJUSTMENT: A LITERATURE REVIEW Professor Charles Desforges with Alberto Abouchaar The views expressed in this report are the authors' and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department for Education and Skills. © Queen’s Printer 2003 ISBN 1 84185 999 0 June 2003 1 Acknowledgements This report was compiled in a very short time thanks to the invaluable help given generously by a number of workers in the field. Outstanding amongst these were Mike Gasper, John Bastiani, Jane Barlow, Sheila Wolfendale and Mary Crowley. I am most grateful for their collegial participation. Most important of all to a review are those who work in the engine room. The search, identification, collection and collation of material and the production aspects of the report are critical. Special thanks are due here to Anne Dinan in the University of Exeter Library, Finally, this work would not have been possible without the limitless support of Zoë Longridge-Berry whom I cannot thank enough. 2 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Researching parental involvement: 6 some conceptual and methodological issues Chapter 3 The impact of parental involvement 17 on achievement and adjustment Chapter 4 How does parental involvement work? -

Volume XII, No

March 31—April 6, 2011 Volume XII, No. 13 Willie Nelson added to line-up for “Kokua For Japan” on April 10 World-renowned entertainer Willie Nelson will perform at “Kokua For Japan,” a Hawai‘i-based radio, television and Internet fund raising event for the victims of the earthquake and tsunami in Japan. The event, staged by Clear Channel Radio Hawaii and Oceanic Time Warner Cable, will take place at the Great Lawn at the Hilton Hawaiian Village Beach Resort & Spa on April 10, 2011 from noon to 5 p.m. All proceeds to benefit the American Red Cross for the Japan earthquake and Pacific tsunami relief efforts. Nelson will join previously announced entertainers including: Henry Kapono with special guests Michael McDonald and Mick Fleetwood; Loretta Ables Sayre; The Brothers Cazimero; Cecilio & Kapono; Kalapana; Cecilio & Kompany; Amy Hanaialii; Na Leo; John Cruz; Natural Vibrations; ManoaDNA; Robi Kahakalau; Mailani; Taimane; Go Jimmy Go; Jerry Santos; Gregg Hammer Band; and Kenny Endo Taiko. On-air personalities from Clear Channel Radio and local broadcast and cable TV stations will host the program. “Kokua For Japan,” a Hawai‘i-based radio, television and Internet fund raising event for the victims of the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, will be held on Sunday, April 10, 2011 from noon to 5 p.m. The event, staged by Clear Channel Radio Hawaii and Oceanic Time Warner Cable, will take place at the Great Lawn at the Hilton Hawaiian Village Beach Resort & Spa. Tickets are available for $15 via Honolulu Box Office. Visit HonoluluBoxOffice.com for on-line purchasing or call 808-550-8457 for charge-by-phone. -

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal

Federal Communications Commission Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BTCCT-20061212AVR Communications, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CCF, et al. (Transferors) ) BTCH-20061212BYE, et al. and ) BTCH-20061212BZT, et al. Shareholders of Thomas H. Lee ) BTC-20061212BXW, et al. Equity Fund VI, L.P., ) BTCTVL-20061212CDD Bain Capital (CC) IX, L.P., ) BTCH-20061212AET, et al. and BT Triple Crown Capital ) BTC-20061212BNM, et al. Holdings III, Inc. ) BTCH-20061212CDE, et al. (Transferees) ) BTCCT-20061212CEI, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212CEO For Consent to Transfers of Control of ) BTCH-20061212AVS, et al. ) BTCCT-20061212BFW, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting – Fresno, LLC ) BTC-20061212CEP, et al. Ackerley Broadcasting Operations, LLC; ) BTCH-20061212CFF, et al. AMFM Broadcasting Licenses, LLC; ) BTCH-20070619AKF AMFM Radio Licenses, LLC; ) AMFM Texas Licenses Limited Partnership; ) Bel Meade Broadcasting Company, Inc. ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; ) CC Licenses, LLC; CCB Texas Licenses, L.P.; ) Central NY News, Inc.; Citicasters Co.; ) Citicasters Licenses, L.P.; Clear Channel ) Broadcasting Licenses, Inc.; ) Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; and Jacor ) Broadcasting of Colorado, Inc. ) ) and ) ) Existing Shareholders of Clear Channel ) BAL-20070619ABU, et al. Communications, Inc. (Assignors) ) BALH-20070619AKA, et al. and ) BALH-20070619AEY, et al. Aloha Station Trust, LLC, as Trustee ) BAL-20070619AHH, et al. (Assignee) ) BALH-20070619ACB, et al. ) BALH-20070619AIT, et al. For Consent to Assignment of Licenses of ) BALH-20070627ACN ) BALH-20070627ACO, et al. Jacor Broadcasting Corporation; ) BAL-20070906ADP CC Licenses, LLC; AMFM Radio ) BALH-20070906ADQ Licenses, LLC; Citicasters Licenses, LP; ) Capstar TX Limited Partnership; and ) Clear Channel Broadcasting Licenses, Inc. ) Federal Communications Commission ERRATUM Released: January 30, 2008 By the Media Bureau: On January 24, 2008, the Commission released a Memorandum Opinion and Order(MO&O),FCC 08-3, in the above-captioned proceeding. -

Dealing with Digital Distractions Full Disclosure Lets Crush the Critic

By Adam Schwebach, Ph.D. Dealing with Digital Distractions Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach,Ph.D. Full Disclosure ❖ I am NOT a perfect parent ❖ I am a Pediatric Neuropsychologist ❖ When it comes to raising children, I have the same fears, worries and concerns you do Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. Lets Crush the Critic ❖ Technology is NOT bad ❖ The human species has always been “advancing” ❖ Like all technological advances, there comes unforeseen consequences and challenges ❖ One must be aware of the potential dangers and pitfalls and discover ways to address those issues Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. Technological Advances that Have Changed Mankind Forever ❖ Electricity ❖ Plastic ❖ Automobile ❖ Airplanes ❖ Microchip ❖ TV ❖ Internet ❖ Mobile Technology (i.e., cell phones) Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. Lets Talk About Mobile Technology Copyright 2018 Adm J. Schwebach, Ph.D. History of Cell Phones Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. 1G Phones Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. 1973 First Cell phone Call by Dr. Cooper Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. 2G Phones Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. 2G Phones ❖ In the 1990’s technology advances from “analog” to “digital” ❖ Instead of just being able to make phone calls, digital technology allows people to transmit “data” ❖ In 1993, the first mobile to mobile text message is sent in in Finland Copyright 2018 Adam J. Schwebach, Ph.D. 3G Phones ❖ Increase in band width and mobile storage allows for quicker speeds, live streaming and the ability to “download” data onto a mobile device Copyright 2018 Adam J. -

KCC Professor of Art Awarded Excellence in Teaching Medal

NO REISMAN FOR TIMMY CHANG, PAGE 3 I SNAKES A THREAT TO THE ISLAND, PAGE 5 I LEARN TO SURF LKE A PRO, PAGE 7 The Kapi'o Newspress Tuesday, September 21,2004 THE KAPI'OLANI COMMUNITY COLLEGE NEWSWEEKLY Volume # 38 Issue 5 KCC Professor of Art Awarded Hawaii teen arrested in Excellence in Teaching Medal NYC protests By Chad Thompson-Smith riot gear who used orange netting By Ami Blodgett STAFF WRITER to surround us. At that point, the ONLINE EDITOR I always entire group was arrested. When one More than 1,000 protestors were woman asked why they were being Kauka de Silva, professor of art, wanted to do arrested during the Republican arrested the cops responded they was the only teacher from Kapio art, always, National Convention according to didn't know and you will find out lani Community College to be hon the New York Tunes. One of those when you get where you are going. ored by the University of Hawaii always ... l detained was seventeen-year-old Among the arrested was a 17-year Board of Regents with one of 14 started doing Hawaii high school student, Annie old tourist from Germany that had Excellence in Teaching Medals for Elfing. Elfing was arrested with a been out shopping and had noth 2004. ceramics at group of approximately 40 other ing to do with the protest; another "I was really surprised and it Kamehameha people. was a New York native that had just really means a lot to me," de Silva "I was with about eight other stepped out to grab a newspaper. -

Honolulu's Mayor Ends Proposal for Rail Line in Downtown Are

HONOLULU'S MAYOR ENDS PROPOSAL FOR RAIL LINE IN DOWNTOWN ARE... Page 1 of 2 June 28, 1981 HONOLULU'S MAYOR ENDS PROPOSAL FOR RAIL LINE IN DOWNTOWN AREA By WALLACE TURNER Mayor Eileen Anderson has declined to accept $5 million in Federal funds for an engineering survey, ending plans for a commuter rail system through downtown Honolulu. ''Why spend $5 million on a system that won't be built?'' Mayor Anderson asked recently in defending her position. ''We don't need a $5 million study to make our decision.'' She said she had decided to expand the bus system, adding 80 to 100 new vehicles to the 400 in operation. In the decade when it was under consideration by the administration of the previous Mayor, Frank F. Fasi, the rail system became known as HART, an acronym for Honolulu Area Rapid Transit. Plans called for a system of various lengths, the greatest being a 23-mile run between Aloha Stadium at Pearl City and Hawaii Kai to the east, beyond Diamond Head. Honolulu lies along the lower slopes of headlands so that traffic moving east and west must pass through narrow corridors. As a result the roads are extremely congested in the morning and evening. Cars Popular on Island ''There are about 400,000 vehicles on this island,'' said Roy Parker, the head of Honolulu's transportation department. ''We are like Los Angeles about cars. Over one period, when we measured that the Oahu population had gone up 100 percent, we found that vehicle registrations had gone up 165 percent.'' When Mayor Anderson took office in January, the issue was whether to do the preliminary engineering for the first stretch of HART, eight miles running through the downtown area from Honolulu International Airport to the University of Hawaii. -

University of Hawai'i System

University of Hawai‘i System Native Hawaiian Student Programs Directory 2011 Initiative of the Pūkoʻa Council He Pūkoʻa e kani ai ka ʻĀina ―A grain of coral eventually grows into land.‖ 1 Table of Contents Purpose and Function of the Pūkoʻa Council 3 University of Hawai‘i System Scholarship Opportunities 4 Hawaiʻi Island Hawaiʻi Community College 7 University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo 8 University of Hawaiʻi —West Hawaiʻi Center 14 Kauaʻi Island Kauaʻi Community College 15 Lānaʻi Island Lānaʻi High & Elementary School 17 Maui Island University of Hawai‗i Maui College 18 Molokaʻi Island Molokaʻi Educational Center 21 Oʻahu Island Honolulu Community College 21 Kapiʻolani Community College 24 Leeward Community College 27 Windward Community College 29 University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa 31 University of Hawaiʻi West Oʻahu 44 2 Purpose and Function of the Pūkoʻa Council The purpose of the Pūkoʻa Council of the University of Hawaiʻi is to provide a formal, independent voice and organization through which the Native Hawaiian faculty, administrators, and students of the University of Hawaiʻi system can participate in the development and interpretation of system-wide policy and practice as it relates to Native Hawaiian programs, activities, initiatives, and issues. Specifically, the Council will: 1. Provide advice and information to the President of the University, on issues that have particular relevance for Native Hawaiians and for Native Hawaiian culture, language, and history. 2. Work with the system and campus administration to position the University as one of the world's foremost indigenous-serving universities. 3. Promote the access and success of Native Hawaiian students in undergraduate, graduate and professional programs, and the increase in representation of Native Hawaiians in all facets of the University. -

The American Legion 55Th National Convention: Official Program And

i 55 th NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE r r ~7T~rwmm T sr m TTi rri T r M in ml 1 15', mwryf XI T TT\W i TI Til J r, if A 1 m 3 tim i j g T Imp. Xi I xl m | T 1 n “Hi ^ S 1 33 1 H] I ink §j 1 1 ""fm. Jjp 1 — 1 ZD ^1 fll i [mgj*r- 11 >1 "PEPSI-COLA," "PEPSI," AND "TWIST-AWAY" ARE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF PepsiCo, INC. Nothing downbeat here ... no blue notes. That’s because Pepsi- Cola delivers the happiest, rousingest taste in cola. Get the one with a lot to give. Pass out the grins with Pepsi . the happiest taste in cola. Ybu’ve got a lot to live. Pepsi’s got a lot to give. ; FOR^fSr OD ANDJK. OUNTRY THE AMERICAN LEGION 55 th National Convention WE ASSOCIATE OURSELVES TOGETHER FOR THE FOLLOWING PURPOSES To uphold and defend the Constitution of the United States of America; to maintain law and order; to foster and perpetuate a one hundred percent Americanism to preserve the memories and incidents of our associations in the Great Wars; to inculcate a sense of individual obligation to the community, state and nation; SONS OF THE AMERICAN LEGION to combat the autocracy of both the classes and the masses; to make right the 2nd National Convention master of might; to promote peace and good will on earth; to safeguard and transmit to posterity the principles of justice, freedom and democracy; to consecrate and sanctify our comradeship by our devotion to mutual helpfulness. -

DI SB441 F1 Ocrcombined.Pdf

March 5, 1980 The Honorable Dennis O’Connor The Senate The Tenth Legislature State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Dennis: I regret that I will not be in Hawaii on March 5, 1980, and therefore will not be able to attend the performance of ’’Big Boys Don’t Cry” and to view the display of pottery done by prisoners from the Kalihi-Palama Ceramics Class. Please convey my congratulations to the director of the play, Tremaine Tamayose, and to the teacher of the ceramics class, Mary Ellen Hankock, as well as the participants in the two programs. Aloha DANIEL K. INOUYE United States Senator DKI:jmpl I regret that I will not be able to attend the performance of "Big Boys Don't Cry" and to view the display of pottery done by prisoners from the Kalihi-Palam Ceramics Class. Please convey my congratulations to the director of the play Tremaine Tamayose, and to the teacher of the ceramics class* Mary Ellen Hankock, as well as the participants in the two programs. Aloha, DKI STATE SENATE PTj May 5, 1980 Mr. Seichi Hirai Clerk of the Senate The Tenth Legislature State of Hawaii Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Dear Shadow: This will acknowledge your recent communication transmitting a copy of Resolution No. 235, adopted by the State Senate during the regular session of 1980, which expresses the support of the Senate for a bikeway between Waimea and Kekaha, Kauai, Your thoughtfulness in sharing the abovementioned Resolution with me is most appreciated. Aloha, DANIEL K. INOUYE United States Senator DKI:jmpl RICHARD S. -

No. 24 Mormon Pacific Historical Society

Mormon Pacific Historical Society Proceedings 24th Annual Conference October 17-18th 2003 (Held at ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel in Honolulu) ‘Auwaiolimu Chapel (circa 1890’s) Built by Elder Matthew Noall Dedicated April 29, 1888 (attended by King Kalakaua and Queen Kapi’olani) 1 Mormon Pacific Historical Society 2003 Conference Proceedings October 17-18, 2003 Auwaiolimu (Honolulu) Chapel Significant LDS Historical Sites on Windward Oahu……………………………….1 Lukewarm in Paradise: A Mormon Poi Dog Political Journalist’s Journey ……..11 into Hawaii Politics Alf Pratte Musings of an Old “Pol” ………………………………………………………………32 Cecil Heftel World War Two in Hawaii: A watershed ……………………………………………36 Mark James It all Started with Basketball ………………………………………………………….60 Adney Komatsu Mormon Influences on the Waikiki entertainment Scene …………………………..62 Ishmael Stagner My Life in Music ……………………………………………………………………….72 James “Jimmy” Mo’ikeha King’s Falls (afternoon fieldtrip) ……………………………………………………….75 LDS Historical Sites (Windward Oahu) 2 Pounders Beach, Laie (narration by Wylie Swapp) Pier Pilings at Pounders Beach (Courtesy Mark James) Aloha …… there are so many notable historians in this group, but let me tell you a bit about this area that I know about, things that I’ve heard and read about. The pilings that are out there, that you have seen every time you have come here to this beach, are left over from the original pier that was built when the plantation was organized. They were out here in this remote area and they needed to get the sugar to market, and so that was built in order to get the sugar, and whatever else they were growing, to Honolulu to the markets. These (pilings) have been here ever since. -

Special Report: Dxing in Oahu After the Quake

7 Special Report: DXing in Oahu After The Quake By Dale Park Following are loggings made in the aftermath of the 6.7-Richter scale earthquake that struck Ha- waii October 15 at 7:08 am (1308 ELT), followed a few minutes later by a 5.8 aftershock. Fortunately, the quakes only caused isolated damage to Oahu, but it was the island-wide blackout that occurred about 7:11 that riled everybody. The failure that occurred when the earthquake hit triggered a shutdown of Hawaiian Electric’s three power plants a few minutes later (and three minutes before the aftershock). The power failure at my home lasted until 11:20 PM (10/16 0520 ELT), 16 hours later. Blackouts also occurred on the Big Island and Maui, but most of those islands’ power was restored within a few hours. Initially the stations in Honolulu that stayed on were KSSK AM 590 and FM 92.3 and KUCD-FM 101.9, followed later by KRTR 650 and KKNE 940. KHNR 870 came on later only to go off again, but sister station KHUI-FM 99.5 remained on in the afternoon. Listening equipment: Sangean ATS-818CS, Terk AM1000 loop, lots of candles. Station News During/After the Quake (Times in ELT): 590 KSSK HI Honolulu. 10/15 1341. Station finally broke into a pre-taped interview to be- gin live coverage of the island-wide power failure. Station is designated as the main information station for state Civil Defense and has its own emer- gency generator. Programming was relayed on sister stations KSSK-FM 92.3 and KUCD-FM 101.9. -

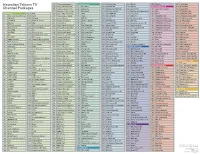

Hawaiian Telcom TV Channel Packages

Hawaiian Telcom TV 604 Stingray Everything 80’s ADVANTAGE PLUS 1003 FOX-KHON HD 1208 BET HD 1712 Pets.TV 525 Thriller Max 605 Stingray Nothin but 90’s 21 NHK World 1004 ABC-KITV HD 1209 VH1 HD MOVIE VARIETY PACK 526 Movie MAX Channel Packages 606 Stingray Jukebox Oldies 22 Arirang TV 1005 KFVE (Independent) HD 1226 Lifetime HD 380 Sony Movie Channel 527 Latino MAX 607 Stingray Groove (Disco & Funk) 23 KBS World 1006 KBFD (Korean) HD 1227 Lifetime Movie Network HD 381 EPIX 1401 STARZ (East) HD ADVANTAGE 125 TNT 608 Stingray Maximum Party 24 TVK1 1007 CBS-KGMB HD 1229 Oxygen HD 382 EPIX 2 1402 STARZ (West) HD 1 Video On Demand Previews 126 truTV 609 Stingray Dance Clubbin’ 25 TVK2 1008 NBC-KHNL HD 1230 WE tv HD 387 STARZ ENCORE 1405 STARZ Kids & Family HD 2 CW-KHON 127 TV Land 610 Stingray The Spa 28 NTD TV 1009 QVC HD 1231 Food Network HD 388 STARZ ENCORE Black 1407 STARZ Comedy HD 3 FOX-KHON 128 Hallmark Channel 611 Stingray Classic Rock 29 MYX TV (Filipino) 1011 PBS-KHET HD 1232 HGTV HD 389 STARZ ENCORE Suspense 1409 STARZ Edge HD 4 ABC-KITV 129 A&E 612 Stingray Rock 30 Mnet 1017 Jewelry TV HD 1233 Destination America HD 390 STARZ ENCORE Family 1451 Showtime HD 5 KFVE (Independent) 130 National Geographic Channel 613 Stingray Alt Rock Classics 31 PAC-12 National 1027 KPXO ION HD 1234 DIY Network HD 391 STARZ ENCORE Action 1452 Showtime East HD 6 KBFD (Korean) 131 Discovery Channel 614 Stingray Rock Alternative 32 PAC-12 Arizona 1069 TWC SportsNet HD 1235 Cooking Channel HD 392 STARZ ENCORE Classic 1453 Showtime - SHO2 HD 7 CBS-KGMB 132