Georgia Domestic Violence Benchbook Joan Prittie & Nancy Hunter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama Western Division

Case 7:13-cv-08056-IPJ Document 4 Filed 01/15/14 Page 1 of 20 FILED 2014 Jan-15 PM 12:51 U.S. DISTRICT COURT N.D. OF ALABAMA IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA WESTERN DIVISION BRANDON TERRELL PEEBLES, ) ) Petitioner, ) ) v. ) CV: 13-cv-08056-IPJ ) CR: 10-cr-00144-IPJ-HGD-1 ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Respondent. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Petitioner Brandon Terrell Peebles moves the court to vacate, set aside, or correct his sentence pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2255 (doc. 1). Peebles entered a “blind” guilty plea, and the court entered judgment against him on March 2, 2011 (crim. doc. 16). Peebles pleaded guilty to one count of Carjacking in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 2119 (Count One), and one count of Carrying a Firearm During and in Relation to a Crime of Violence in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 924(c)(1)(A)(ii) (Count Two). Id. The court sentenced Peebles to a term of sixty months on Count One and a consecutive term of eighty-four months on Count Two. Id. Peebles did not appeal the court’s judgment. 1 Case 7:13-cv-08056-IPJ Document 4 Filed 01/15/14 Page 2 of 20 Peebles filed the instant 2255 motion on December 16, 2013 (doc. 1).1 The court ordered the United States to show cause as to why Petitioner should be denied relief (doc. 2). The United States filed its response in opposition to Petitioner’s motion on January 8, 2014 (doc. -

ROYAL SQUARE SHOPPING CENTER 768 Putney Road (Route 5) Brattleboro, VT 05301

COVER OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS SITE PLAN AERIAL CENTER PHOTOS CONTACT ROYAL SQUARE SHOPPING CENTER 768 Putney Road (Route 5) Brattleboro, VT 05301 ALDI • STAPLES • PEEBLES • PLANET FITNESS COVER OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS SITE PLAN AERIAL CENTER PHOTOS CONTACT ROYAL SQUARE SHOPPING CENTER 768 Putney Road (Route 5) Brattleboro, VT 05301 ALDI • STAPLES • PEEBLES PLANET FITNESS Royal Square is a highly trafficked, 108,000 square foot shopping center featuring ALDI, Staples, Peebles, Planet Fitness, and Mattress Firm. The center bustles because this excellent mix of stores meets the daily needs of today’s busy consumer. LOCATION TRADE AREA AVERAGE DAILY TRAFFIC The center is just off Exit 3 of I-91 and Brattleboro is a regional draw for I-91 at Exit 3: 25,000 neighbored by Hannaford, Rite Aid, shopping and services to all the Putney Road/Route 5: 15,000 McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Advanced Auto, surrounding southeastern and Family Dollar. Vermont towns. (2018 SitesUSA) The center boasts a signalized entrance and plentiful parking. Management & Leasing by Wilder | www.wilderco.com MAy 2019 COVER OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS SITE PLAN AERIAL CENTER PHOTOS CONTACT ROYAL SQUARE SHOPPING CENTER 768 Putney Road (Route 5) Brattleboro, VT 05301 ALDI • STAPLES • PEEBLES PLANET FITNESS 2018 ESTIMATES 5 MILES 10 MILES 20 MIN DRIVE Population 15,590 30,817 47,566 Average HH Income $71,376 $78,461 $80,504 Median Age 44.3 yrs 45.3 yrs 44.5 yrs 10 MIN DRIVE 15 MIN DRIVE 20 MIN DRIVE Workplace Population 14,915 17,515 30,259 (2018 SitesUSA) Management & Leasing by Wilder | www.wilderco.com -

Stage Stores Completes the Acquisition of Bc Moore & Sons, Inc

Exhibit 99.2 NEWS RELEASE CONTACT: Bob Aronson Vice President, Investor Relations 800-579-2302 ([email protected]) FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE STAGE STORES COMPLETES THE ACQUISITION OF B.C. MOORE & SONS, INC. HOUSTON, TX, February 27, 2006 - Stage Stores, Inc. (Nasdaq: STGS) today reported that it has completed its previously announced acquisition of privately held B.C. Moore & Sons, Inc. (“B.C. Moore”). In purchasing B.C. Moore, the Company acquired 78 retail locations, which are located in small markets throughout Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina. The Company’s integration plan calls for 69 of the acquired locations to be converted into Peebles stores, and the remaining 9 locations will be closed. The acquisition expands and strengthens the Company’s position in the Southeastern United States, and is consistent with its corporate strategy of increasing the concentration of its store base into smaller and more profitable markets. Jim Scarborough, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Stage, commented, “We are pleased to have completed this acquisition so quickly, and we enthusiastically look forward to entering these new markets with our Peebles store format. Our new customers in these markets will enjoy our exceptional service, exciting brand names, merchandise selections, and value in easy-to-shop and conveniently located stores.” Stage Stores, Inc. brings nationally recognized brand name apparel, accessories, cosmetics and footwear for the entire family to small and mid-size towns and communities. The Company currently operates 376 Bealls, Palais Royal and Stage stores throughout the South Central states, and operates 174 Peebles stores throughout the Midwestern, Southeastern, Mid-Atlantic and New England states. -

The Peebles Path to Real Estate Wealth How to Make Money in Any Market

P1: OTA/XYZ P2: ABC FM JWBK256/Peebles June 30, 2008 7:48 Printer Name: Malloy, Ann Arbor, Michigan The Peebles Path to Real Estate Wealth How to Make Money in Any Market R. Donahue Peebles with J.P. Faber John Wiley & Sons, Inc. i P1: OTA/XYZ P2: ABC FM JWBK256/Peebles June 30, 2008 7:48 Printer Name: Malloy, Ann Arbor, Michigan xii P1: OTA/XYZ P2: ABC FM JWBK256/Peebles June 30, 2008 7:48 Printer Name: Malloy, Ann Arbor, Michigan The Peebles Path to Real Estate Wealth How to Make Money in Any Market R. Donahue Peebles with J.P. Faber John Wiley & Sons, Inc. i P1: OTA/XYZ P2: ABC FM JWBK256/Peebles June 30, 2008 7:48 Printer Name: Malloy, Ann Arbor, Michigan Copyright C 2008 by R. Donahue Peebles. All rights reserved. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey. Published simultaneously in Canada. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at www.wiley.com/go/permissions. -

This Is Not a Mall.1

This is not a mall.1 The Macerich Company ANNUAL REPORT 2001 For additional information about Macerich, our Form 10-K for the year ended December 31, 2001 is included in this Annual Report for your review. 2001 2000 1999 1998 1997 (All amounts in thousands, except per share and property data) OPERATING DATA Total revenues $ 334,573 $ 320,092 $ 327,444 $ 283,861 $ 221,214 Shopping center and operating expenses $ 110,827 $ 101,674 $ 100,327 $ 89,991 $ 70,901 REIT general and administrative expenses $ 6,780 $ 5,509 $ 5,488 $ 4,373 $ 2,759 Earnings before interest, income taxes, depreciation, amortization, minority interest, extraordinary items, gain (loss) on sale of assets and preferred dividends (EBITDA) – includes joint ventures at their pro rata share (1) $ 323,798 $ 314,628 $ 301,803 $ 230,362 $ 154,140 Net income $ 77,723 $ 56,929 $ 129,011 $ 44,075 $ 22,046 Net income per share – diluted $ 1.72 $ 1.11 $ 2.99 $ 1.06 $ 0.85 OTHER DATA FFO – diluted (2) $ 175,068 $ 167,244 $ 164,302 $ 120,518 $ 83,427 Cash distributions declared per common share $ 2.14 $ 2.06 $ 1.965 $ 1.865 $ 1.78 Portfolio occupancy at year end 92.4% 93.3% 92.8% 93.2% 91.8% Average tenant sales per square foot – mall and freestanding stores $ 350 $ 349 $ 336 $ 319 $ 317 BALANCE SHEET DATA Investment in real estate (before accumulated depreciation) $ 2,227,833 $ 2,228,468 $ 2,174,535 $ 2,213,125 $ 1,607,429 Total assets $ 2,294,502 $ 2,337,242 $ 2,404,293 $ 2,322,056 $ 1,505,002 Total mortgage, notes and debentures payable $ 1,523,660 $ 1,550,935 $ 1,561,127 $ 1,507,118 $ 1,122,959 Minority interest (3) $ 113,986 $ 120,500 $ 129,295 $ 132,177 $ 100,463 Common stockholders’ equity plus preferred stock $ 596,290 $ 609,608 $ 648,590 $ 610,760 $ 216,295 (1) EBITDA, as presented, may not be comparable to similarly titled measures reported by other companies. -

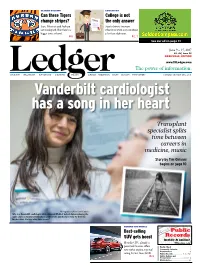

Vanderbilt Cardiologist Has a Song in Her Heart

CLIMER COLUMN Can these Tigers change stripes? Sure, Missouri and Auburn are misaligned. But there’s a bigger issue at hand. EDUCATION College is not P13 the only answer State’s drive to increase DAVIDSONLedger • WILLIAMSON • RUTHERFORD • CHEATHAM WILSON SUMNER• ROBERTSON • MAURY • DICKSONeducation • MONTGOMERY levels is more about jobs than diplomas. P2, 7 Vanderbilt cardiologist See our ad on page 13 has a song in her heart June 9 – 15, 2017 The power of information.NASHVILLE Vol. 43 EDITION | Issue 23 www.TNLedger.com FORMERLY WESTVIEW SINCE 1978 Page 13 Dec.: Dec.: Keith Turner, Ratliff, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Resp.: Kimberly Dawn Wallace, Atty: Mary C Lagrone, 08/24/2010, 10P1318 In re: Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates, Jeanan Mills Stuart, Princess Angela Gates,Dec.: Resp.: Kim Prince Patrick, Angelo Terry Patrick, Transplant Gates, Atty: Monica D Edwards, 08/25/2010, 10P1326 In re: Keith Turner, TN Dept Of Correction, specialist splits TN Dept Of Correction, Resp.: Johnny Moore, Atty: Bryce Coatney, www.westviewonline.com Dec.: Melinda L Tomlinson, Resp.: Pltf(s): Rodney A Hall, Pltf Atty(s): n/a, 08/27/2010, 10P1336 In re: Kim Patrick, Terry Patrick, Pltf(s): Sandra Heavilon, Resp.: Jewell Tinnon, Atty: Ronald Andre Stewart, 08/24/2010,Dec.: Seton Corp 10P1322 Insurance Company, Dec.: Regions Bank, Resp.: Leigh A Collins, In re: Melinda L Tomlinson, Def(s): Jit Steel Transport Inc, National Fire Insurance Company, Elizabeth D Hale, Atty: William Warner McNeilly, 08/24/2010, time betweenDef Atty(s): J Brent Moore, 08/26/2010, -

MEMORANDUM OPINION. Signed by Judge Deborah K. Chasanow

Franklin v. Jackson et al Doc. 12 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MARYLAND : RENEE FRANKLIN : v. : Civil Action No. DKC 14-0497 : CLARENCE JACKSON, et al. : MEMORANDUM OPINION Presently pending and ready for resolution in this Church dispute is the motion to dismiss or, in the alternative, for summary judgment, filed by Defendants Clarence Jackson, Gloria McClam-Magruder, Denise Killen, Clifford Boswell, Dorothy Williams, Lynda Pyles, and Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc.1 (ECF No. 7). The issues have been fully briefed, and the court now rules, no hearing being deemed necessary. Local Rule 105.6. For the following reasons, Defendants’ motion will be granted. I. Background This lawsuit arises from a longstanding dispute concerning the control and governance of Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (“the Church”), located in Landover, Prince George’s County, Maryland. The sanctuary is known as the “Jericho City of Praise.” (ECF No. 7-19). 1 The parties refer to Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. as the “Nominal Defendant.” Dockets.Justia.com Plaintiff Renee Franklin (“Plaintiff”) brings this action derivatively on behalf of the Church against Defendants Clarence Jackson, Gloria McClam-Magruder, Denise Killen, Clifford Boswell, Dorothy Williams, and Lynda Pyles (collectively, “the Board” or “Defendant Trustees”), who are trustees on the Board of Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (“Jericho Maryland”), a Maryland non-stock religious corporation formed to manage the assets, estate, property, interests, and inheritance of the Church. (ECF No. 7-8).2 According to the complaint, in 1962, the late Bishop James R. Peebles, Sr. and Apostle Betty Peebles created a District of Columbia non-profit religious corporation to conduct business on behalf of the Church. -

In the Supreme Court of Florida

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA THE FLORIDA BAR, Supreme Court Case No. SC- Complainant, The Florida Bar File v. No. 2016-30,084(18C) ARMANDO EDUARDO ROSAL, Respondent. ___________________________/ COMPLAINT The Florida Bar, complainant, files this Complaint against Armando Eduardo Rosal, respondent, pursuant to the Rules Regulating The Florida Bar and alleges: 1. Respondent is, and at all times mentioned in the complaint was, a member of The Florida Bar, admitted on March 9, 1992, and is subject to the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court of Florida. 2. Respondent practiced law in Brevard County, Florida, at all times material. 3. The Eighteenth Judicial Circuit Grievance Committee "C" found probable cause to file this complaint pursuant to Rule 3-7.4, of the Rules Regulating The Florida Bar, and this complaint has been approved by the presiding member of that committee. 4. In or around October 2014, respondent filed an Amended Petition for Summary Administration in the matter, In re: Estate of Trevor Hamilton, Case No. 2013-CP-70141, in the Circuit Court of Brevard County, Florida. 5. Respondent filed the Amended Petition for Summary Administration on behalf the petitioner Jewell Lewis. 6. Respondent was retained by Tamar Peebles, his former client and a relative of Ms. Lewis, to handle the probate matter. Respondent received a legal fee from Ms. Peebles to do so. 7. Respondent improperly relied on Ms. Peebles’ assertions that Ms. Lewis had requested that respondent represent her in the probate matter. 8. Respondent never spoke with Ms. Lewis regarding the probate case. Respondent never clarified the scope of the representation and disposition of the estate assets with Ms. -

People First of Alabama V. Merrill

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA PEOPLE FIRST OF ALABAMA, ROBERT CLOPTON, ERIC PEEBLES, HOWARD PORTER, JR., ANNIE CAROLYN THOMPSON, GREATER BIRMINGHAM MINISTRIES, and the ALABAMA STATE Case No.: __________________ CONFERENCE OF THE NAACP, COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE Plaintiffs, AND DECLARATORY RELIEF v. JOHN MERRILL, in his official capacity as the Secretary of State of Alabama, KAY IVEY, in her official capacity as the Governor of the State of Alabama, the STATE OF ALABAMA, ALLEEN BARNETT, in her official capacity as Absentee Election Manager of Mobile County, Alabama; JACQUELINE ANDERSON-SMITH, in her official capacity as Circuit Clerk of Jefferson County, Alabama; KAREN DUNN BURKS, in her official capacity as Deputy Circuit Clerk of the Bessemer Division of Jefferson County, Alabama; and MARY B. ROBERSON, in her official capacity as Circuit Clerk of Lee County, Alabama, Defendants. INTRODUCTION 1. Plaintiffs People First of Alabama, Robert Clopton, Eric Peebles, Howard Porter, Jr., Annie Carolyn Thompson, Greater Birmingham Ministries, and the Alabama State Conference of the NAACP, file this Complaint for immediate injunctive and declaratory relief against the Defendants Secretary of State John Merrill, Governor Kay Ivey, the State of Alabama, Mobile County Absentee Election Manager Alleen Barnett, Jefferson County Circuit Clerk Jacqueline Anderson-Smith, Deputy Circuit Clerk of the Bessemer Division of Jefferson County Karen Dunn Burks, and Lee County Circuit Clerk Mary B. Roberson for failing to take adequate steps to protect the fundamental right to vote ahead of the 2020 elections, including the July 14, 2020 primary runoff election, in the midst of the unprecedented national and statewide COVID-19 public health crisis. -

The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777 ______

The British Gerald Kauffman is a member of the The British Invasion of public policy and engineering faculty at Invasion the University of Delaware. Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777 Michael Gallagher is a member of the of Sons of the American Revolution. Delaware, Aug-Sep During the American War for Independence in August and 1777 September, 1777, the British invaded Delaware as part of an end-run campaign to defeat George Washington and the Americans and capture the capital at Philadelphia. For a few short weeks the hills and streams in and around Newark and Iron Hill and at Cooch's Bridge along the Christina River were the focus of world history as the British marched through the Diamond State between the Chesapeake Bay and Brandywine Creek. This is the story of the British invasion of Delaware, one of the lesser known but critical watershed moments in American history. Kauffman Gerald J. Kauffman Michael R. Gallagher ISBN 978-1-304-28716-8 90000 and Gallagher ID: 9992111 www.lulu.com 9 781304 287168 The British Invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777 __________________________________ A Watershed Moment in American History Gerald J. Kauffman and Michael R. Gallagher www.lulu.com Published by www.lulu.com Copyright © 2013 by Gerald J. Kauffman & Michael R. Gallagher All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher and the authors. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kauffman, Gerald J. The British invasion of Delaware, Aug-Sep 1777 Gerald J. Kauffman and Michael R. -

Downtown Strasburg Economic Restructuring Plan

Town of Strasburg VIRGINIA Downtown Strasburg Economic Restructuring Plan December, 2014 Assistance Provided by: Community Planning Partners, Inc. & Smither Design ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Economic Restructuring Plan was assembled with the assistance of the Management Team assembled for the Downtown Strasburg Revitalization Planning. The input of the members was invaluable to its development and are hereby acknowledged and thanked for their service. Members, including who they represented and/or the role they played are listed below: Barbara Adamson Historian, Strasburg Historical Group Jamie Book Resident Byron Brill Downtown Property Owner Steve Damron Virginia Department of Transportation Brandon Davis Shenandoah County Doug Ellis VA Department of Housing & Community Development Bob Flanagan Strasburg Planning Commission Mike Gochenour Media, Northern Virginia Daily Felicia Hart Downtown Coordinator, Town Staff James Massey Strasburg Architectural Review Board Kimberly Murray Economic Development & Planning Manager, Town Staff Rich Orndorff Chamber of Commerce Judson Rex Town Manager, Town Staff Kelly Sager Downtown Business Owner Alex Schweiger Northern Shenandoah Valley Regional Commission Kate Sowers Hometown Strasburg Mayor Tim Taylor Shenandoah County Schools Scott Terndrup Strasburg Town Council TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Will Be 21 in July Next. John Peebles Died, 1801, Testate. Mary Married in Kyle of Rockingham

will be 21 in July next. John Peebles died, 1801, testate. Mary married in Kyle of Rockingham. He has lately bcc<> 1816. Jane was driven to seek refuge with John Devericks of Pendleton, by Samuel Hemphill, Sr., to his son, S;; who married her mother's sister. John Peebles, Jr., has moved to Kentucky had also two other sons, John and RoL> and Thomas Peebles (son of John, Sr.) to Missouri. Thomas Wilson died Smith, who has conveyed to his son, A1 September, 1818. Robert Carlile deposes, 1818, he has known John Peoples Agnes, his wife, is one of defendants. of Bath from 1774. John married Frances Peoples. Thos. Wilson lived in Hemphill, Sr.?) Deed, 20th June, 1809 1795, was living in Pendleton County. In 1798 he moved to Rockbridge. his wife) Hemphill, Jacob KTiller and Ay Frances died June, 1799. Will of John Peebles dated 19th May, 3800. to Robert Hemphill of Rockingham, tract Wife, Jane; son, Thomas, in Kentucky; son, Robert; son-in-law, Thos. Patent to Samuel Hemphill, 20th July, Wilson, John Erwin, John Devericks ; two grandchildren, daughters of Thos. Also patent to Robert Cravens, 10th Febr Wilson; daughters, jane, Mary; son, John; son Robert's son, John; son This deed has no certificate of record. \ John's son, John. Recorded in Bath, September, 1802. ingham. Eldest son, John, lands adjoini Griner vs. McCoy—O. S. 280; N. S. 99—Bill, 1817. Aaron Kec of Thos. Harrison, deceased, and John "P< Pendleton died (1815-1817), leaving widow Catherine and 5 infant chil- with privilege at any of the fireplaces in dren, viz: James, Peggy, John, Eliza, Joseph.