Frequently Asked Questions on Repo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repo Haircuts and Economic Capital: a Theory of Repo Pricing Wujiang Lou1 1St Draft February 2016; Updated June, 2020

Repo Haircuts and Economic Capital: A Theory of Repo Pricing Wujiang Lou1 1st draft February 2016; Updated June, 2020 Abstract A repurchase agreement lets investors borrow cash to buy securities. Financier only lends to securities’ market value after a haircut and charges interest. Repo pricing is characterized with its puzzling dual pricing measures: repo haircut and repo spread. This article develops a repo haircut model by designing haircuts to achieve high credit criteria, and identifies economic capital for repo’s default risk as the main driver of repo pricing. A simple repo spread formula is obtained that relates spread to haircuts negative linearly. An investor wishing to minimize all-in funding cost can settle at an optimal combination of haircut and repo rate. The model empirically reproduces repo haircut hikes concerning asset backed securities during the financial crisis. It explains tri-party and bilateral repo haircut differences, quantifies shortening tenor’s risk reduction effect, and sets a limit on excess liquidity intermediating dealers can extract between money market funds and hedge funds. Keywords: repo haircut model, repo pricing, repo spread, repo formula, repo pricing puzzle. JEL Classification: G23, G24, G33 A repurchase agreement (repo) is an everyday securities financing tool that lets investors borrow cash to fund the purchase or carry of securities by using the securities as collateral. In its typical transaction form, the borrower of cash or seller sells a security to the lender at an initial purchase price and agrees to purchase it back at a predetermined repurchase price on a future date. On the repo maturity date T, the lender (or the buyer) sells the security back to the borrower. -

Asx Clear – Acceptable Collateral List 28

et6 ASX CLEAR – ACCEPTABLE COLLATERAL LIST Effective from 20 September 2021 APPROVED SECURITIES AND COVER Subject to approval and on such conditions as ASX Clear may determine from time to time, the following may be provided in respect of margin: Cover provided in Instrument Approved Cover Valuation Haircut respect of Initial Margin Cash Cover AUD Cash N/A Additional Initial Margin Specific Cover N/A Cash S&P/ASX 200 Securities Tiered Initial Margin Equities ETFs Tiered Notes to the table . All securities in the table are classified as Unrestricted (accepted as general Collateral and specific cover); . Specific cover only securities are not included in the table. Any securities is acceptable as specific cover, with the exception of ASX securities as well as Participant issued or Parent/associated entity issued securities lodged against a House Account; . Haircut refers to the percentage discount applied to the market value of securities during collateral valuation. ASX Code Security Name Haircut A2M The A2 Milk Company Limited 30% AAA Betashares Australian High Interest Cash ETF 15% ABC Adelaide Brighton Ltd 30% ABP Abacus Property Group 30% AGL AGL Energy Limited 20% AIA Auckland International Airport Limited 30% ALD Ampol Limited 30% ALL Aristocrat Leisure Ltd 30% ALQ ALS Limited 30% ALU Altium Limited 30% ALX Atlas Arteria Limited 30% AMC Amcor Ltd 15% AMP AMP Ltd 20% ANN Ansell Ltd 30% ANZ Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd 20% © 2021 ASX Limited ABN 98 008 624 691 1/7 ASX Code Security Name Haircut APA APA Group 15% APE AP -

Markets Committee Central Bank Collateral Frameworks and Practices

Markets Committee Central bank collateral frameworks and practices A report by a Study Group established by the Markets Committee This Study Group was chaired by Guy Debelle, Assistant Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia March 2013 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2013. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISBN 92-9131-926-0 (print) ISBN 92-9197-926-0 (online) Preface In July 2012, the Markets Committee established a Study Group to take stock of how collateral frameworks and practices compare across central banks and the key changes they have undergone since mid-2007. This initiative followed from the fact that, in the light of recent experience with market stress and other underlying changes in the financial landscape, many central banks have re-examined and adapted their collateral policies. It is also a natural extension of the Committee’s previous work on central bank monetary policy and operating frameworks. The Study Group was chaired by Guy Debelle, Assistant Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia. The Group completed an interim report for review by the Markets Committee in November 2012. The finalised report was presented to central bank Governors of the Global Economy Meeting in early March 2013. The subject matter of this study is of core relevance to central banking. I believe the report could become a reference piece for those who are interested in central bank liquidity operations in different jurisdictions. Moreover, given the growing attention focused on collateral-related issues in the broader financial system, this report, which covers one specific area of collateral practices, could also serve as factual input to the wider debate. -

Changes to DTC Collateral Haircuts

Important Notice The Depository Trust Company B #: 14411-20 Date: December 14, 2020 To: All Participants Category: Settlement From: DTC Risk Management Attention: Settlement Manager/Managing Director/Cashier Subject: Changes to DTC Collateral Haircuts Beginning February 5, 2021, for Settlement Date February 8, 2021, DTC will implement the following changes to modify the collateral value for certain securities, which may affect the value of positions applied to the Collateral Monitor: 1. Securities held as Net Additions in Participant accounts that are issued by any of the issuer banks listed in Table 1 in Appendix A to this Important Notice will be given a 100% haircut and assigned no collateral value. This change is being made to align with provisions of the joint DTC and NSCC committed 364-day line-of-credit facility with a consortium of banks (“LOC Agreement”), as described in greater detail in Appendix A below. 2. United States Agencies and GSE securities that are not rated or that are rated below Aa2/AA will receive a 100% haircut (Appendix B includes the current list of eligible collateral). 3. Zero-coupon United States treasury securities with maturities up to two years will receive a haircut of 2% compared to the current haircut of 5%. This change will provide Participants with additional collateral value for these securities at DTC (Appendix C includes the current list of eligible collateral). 4. Securities with no active market prices will receive a 100% haircut. This will apply to new securities during the initial issuance stage and to active securities where DTC has not received a vendor price the prior day (Appendix C includes the current list of eligible collateral). -

RG96-033 Addition of a New Class of Nasdaq-100 Index® Options Due To

Regulatory Circular RG96-33 Date: April 4, 1996 To: Members and Member Organizations From: Office of the Chairman Re: Addition of a New Class of Nasdaq-100 Index® Options Due to a Change in the Method of Calculating Exercise-Settlement Value Summary: The Chicago Mercantile Exchange (“CME”) anticipates receiving approval from the Commodity Futures Trading Commission to list Nasdaq-100 Index futures and futures options contracts and plans to commence trading in these instruments on Wednesday, April 10, 1996. Nasdaq-100 Index futures contracts at the CME have been designed with a different expiration- settlement value methodology than the calculation used to determine the settlement value currently employed in conjunction with Nasdaq-100 Index Options (ticker symbol NDX and overflow symbol NDZ) at the Chicago Board Options Exchange (“CBOE”). To facilitate hedging and arbitrage strategies by market participants in Nasdaq-100 Index derivatives, the CBOE has filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission an amendment to its rules to allow for a new class of Nasdaq-100 Index Options with an exercise-settlement value calculation methodology which conforms with the one to be employed by the CME. Approval of this rule change is anticipated prior to April 10, 1996. This circular explains the effects of the change on CBOE policies and procedures, and the manner in which existing and new Nasdaq-100 Index Options series will be identified for trading. Ticker Symbol Changes and Nasdaq-100 Index Options Class Addition: To implement this rule change it is necessary to create a new class of Nasdaq-100 Index Options which will be listed in parallel with the existing class. -

Crashes and Collateralized Lending Working Paper

Crashes and Collateralized Lending Jakub W. Jurek Erik Stafford Working Paper 11-025 Copyright © 2010 by Jakub W. Jurek and Erik Stafford Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Crashes and Collateralized Lending Jakub W. Jurek and Erik Stafford∗ Abstract This paper develops a parsimonious static model for characterizing financing terms in collateralized lending markets. We characterize the systematic risk exposures for a variety of securities and develop a simple indifference-pricing framework to value the systematic crash risk exposure of the collateral. We then apply Modigliani and Miller's (1958) Proposition Two (MM) to split the cost of bearing this risk between the borrower and lender, resulting in a schedule of haircuts and financing rates. The model produces comparative statics and time-series dynamics that are consistent with the empirical features of repo market data, including the credit crisis of 2007-2008. First draft: April 2010 This draft: July 2010 ∗Jurek: Bendheim Center for Finance, Princeton University; [email protected]. Stafford: Harvard Business School; estaff[email protected]. We thank Joshua Coval and seminar participants at the University of Oregon for helpful comments and discussions. An important service provided by financial intermediaries in the support of capital market trans- actions is the financing of security purchases by investors. Investors can buy securities with margin, whereby they contribute a portion of the purchase price and borrow the remainder from the intermedi- ary in the form of a collateralized, non-recourse short-term loan. -

Interpretations of FINRA's Margin Rule

3/21 (RN No. 21-13) 174 4210. Margin Requirements (Continued) (f) Other Provisions (Continued) (8) Special Initial and Maintenance Margin Requirements (Continued) member at which a customer seeks to open an account or to resume day trading knows or has a reasonable basis to believe that the customer will engage in pattern day trading, then the special requirements under paragraph (f)(8)(B)(iv) of this Rule will apply. /01 Multiple Purchases and Sales If a customer enters an order to purchase a security and sells the same security within the same day, but for reasons beyond the customer’s control e.g., price, the purchase was executed in smaller blocks, it will be considered as one day trade. However, the member must be able to demonstrate that it was the customer’s intent to execute one day trade. This will also apply to when a customer enters a sale order and buys the same security within the same day. In addition, the trades would have to have been executed in sequential order. One purchase and several subsequent sale transactions of the same security, where the sales were executed in sequential order within the same day, shall constitute one day trade. One sale and several subsequent purchases of the same security, where the purchases were executed in sequential order within the same day, shall also constitute one day trade. /02 Multiple Purchases and Sales – Alternative Method Rather than counting day trades based on the number of transactions a customer executes to establish or increase a position that is liquidated on the same day (as set out in Interpretation /01 above) a firm may instead count day trades based on the number of times during the day that the day trading customer changes its trading direction (i.e., changes from buying a particular security to selling it, or FKDQJHVIURPVHOOLQJDSDUWLFXODUVHFXULW\WREX\LQJLW ௗ Example A: 09:30 Buy 250 ABC 09:31 Buy 250 ABC 13:00 Sell 500 ABC The customer has executed one day trade. -

Haircuts and Initial Margins in the Repo Market

EUROPEAN REPO COUNCIL Haircuts and initial margins in the repo market 8 February 2012 Compiled for ICMA’s European Repo Council by Richard Comotto, Senior Visiting Fellow at the ICMA Centre at the University of Reading Haircuts and initial margins in the repo market 1 Executive summary 1.1 Collateral is intended to hedge default risk. Haircuts/initial margins are usually seen as being intended to hedge the risk on that collateral. From this point of view, they are an adjustment to the quoted market value of a collateral security to take account of the unexpected loss that the repo buyer (seller) in a repo may face due to the difficulty of selling (buying) a collateral security in response to a default by the repo seller (buyer). 1.2 However, haircuts/initial margins appear to vary with counterparty credit risk, albeit weakly. But, although the cause of the default that will trigger the sale or purchase of collateral is most likely to be a counterparty credit event, it is not clear whether or how the size of haircuts/initial margins should be a function of the probability of default of the counterparty. There is a case to be made that the identity of a repo counterparty should only affect haircuts/initial margins in extreme circumstances. 1.3 Theoretical uncertainty about the calculation of haircuts/initial margins is reflected in the wide range of methodologies applied by market users. These range from the intuitive to adaptions of market risk measurement techniques. 1.4 There is also a severe lack of empirical data on haircuts/initial margins. -

SEA Rule 15C3-1

1 NET CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS FOR BROKERS OR DEALERS SEA Rule 15c3-1 (a) NET CAPITAL REQUIREMENTS FOR BROKERS OR DEALERS Every broker or dealer must at all times have and maintain net capital no less than the greater of the highest minimum requirement applicable to its ratio requirement under paragraph (a)(1) of this section, or to any of its activities under paragraph (a)(2) of this section, and must otherwise not be “insolvent” as that term is defined in paragraph (c)(16) of this section. /001 Moment to Moment Net Capital Broker-dealers must maintain sufficient net capital at all times prior to, during and after purchasing or selling proprietary securities. Broker-dealers must have at all times (including intraday) sufficient net capital to meet the haircut requirements of the Capital Rule before taking on any new proprietary positions, even if the intention of the firm is to liquidate or cover the positions before the end of the same day. Broker-dealers are expected to be able to demonstrate moment to moment compliance with the Capital Rule. (SEC Staff to NYSE) (No. 99-8, August 1999) /01 Additional Net Capital Requirement The net capital requirement is increased by one percent of accrued liabilities that are excluded from aggregate indebtedness under the provisions specified at interpretation 15c3-1(c)(2)(iv)(C)/09. (SEC Letter to NASD, July 24, 1984) (No. 87-6, May 1987) /02 Consolidations, Minimum Net Capital Requirement The minimum net capital requirement of the consolidated entity is determined by adding the amount of net capital required for compliance by each consolidated subsidiary subject to the Rule to the minimum dollar net capital requirement of the parent broker-dealer. -

Basel III: the Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools

This standard has been integrated into the consolidated Basel Framework: https://www.bis.org/basel_framework/ Basel Committee on Banking Supervision Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools January 2013 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org). © Bank for International Settlements 2013. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is cited. ISBN 92-9131- 912-0 (print) ISBN 92-9197- 912-0 (online) Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 1 Part 1: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio ..................................................................................... 4 I. Objective of the LCR and use of HQLA ......................................................................... 4 II. Definition of the LCR ..................................................................................................... 6 A. Stock of HQLA ..................................................................................................... 7 1. Characteristics of HQLA ............................................................................. 7 2. Operational requirements ........................................................................... 9 3. Diversification of the stock of HQLA.......................................................... 11 4. Definition of HQLA ................................................................................... -

2021 Q2 Lending and Collateral Q&A

FEDERAL HOME LOAN BANK SYSTEM Lending and Collateral Q&A August 13, 2021 Note - Each answer in this document is written as if it were a stand-alone response. Therefore, some information may be repeated. What is an advance and how do advances work? The FHLBanks provide funding to members and housing associates through secured loans known as advances. Each FHLBank makes advances based on the security of mortgage loans and other types of eligible collateral pledged by the borrowing institutions. Advances are the FHLBanks' largest asset category on a combined basis, representing 50.2% and 51.5% of combined total assets at June 30, 2021 and December 31, 2020. Advances are secured by mortgage loans held in borrower portfolios and other eligible collateral pledged by borrowers. Because members may originate loans that are not sold in the secondary mortgage market, FHLBank advances can serve as a funding source for a variety of mortgages, including those focused on very low-, low-, and moderate-income households. In addition, FHLBank advances can provide interim funding for those members that choose to sell or securitize their mortgages. Each FHLBank develops its advance programs to meet the particular needs of its borrowers, consistent with the safe and sound operation of the FHLBank. Each FHLBank offers a wide range of fixed- and variable-rate advance products with different maturities, interest rates, payment characteristics, and optionality, with maturities ranging from one day to 30 years. Who can borrow from the FHLBanks? The FHLBanks are cooperative institutions, and each FHLBank conducts its advance business almost exclusively with its members and housing associates. -

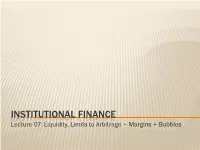

INSTITUTIONAL FINANCE Lecture 07: Liquidity, Limits to Arbitrage – Margins + Bubbles DEBRIEFING - MARGINS

INSTITUTIONAL FINANCE Lecture 07: Liquidity, Limits to Arbitrage – Margins + Bubbles DEBRIEFING - MARGINS $ • No constraints Initial Margin (50%) Reg. T 50 % • Can’t add to your position; • Not received a margin call. Maintenance Margin (35%) NYSE/NASD 25% long 30% short • Fixed amount of time to get to a specified point above the maintenance level before your position is liquidated. • Failure to return to the initial margin requirements within the specified period of time results in forced liquidation. Minimum Margin (25%) • Position is always immediately liquidated MARGINS – VALUE AT RISK (VAR) Margins give incentive to hold well diversified portfolio How are margins set by brokers/exchanges? Value at Risk: Pr (-(pt+1 – pt)¸ m) = 1 % 1% Value at Risk LEVERAGE AND MARGINS j+ j Financing a long position of x t>0 shares at price p t=100: Borrow $90$ dollar per share; j+ Margin/haircut: m t=100-90=10 j+ Capital use: $10 x t j- Financing a short position of x t>0 shares: Borrow securities, and lend collateral of 110 dollar per share Short-sell securities at price of 100 j- Margin/haircut: m t=110-100=10 j- Capital use: $10 x t Positions frequently marked to market j j j payment of x t(p t-p t-1) plus interest margins potentially adjusted – more later on this Margins/haircuts must be financed with capital: j+ j+ j- j- j j+ j- j ( x t m t+ x t m t ) · Wt , where x =xt -xt 1 J with perfect cross-margining: Mt ( xt , …,xt ) · Wt 3.