Omer Fast Der Oylem Iz a Goylem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omer Fast: Nostalgia

Press Release Whitney Museum of American Art Contact: 945 Madison Avenue at 75th Street Stephen Soba New York, NY 10021 Molly Gross whitney.org/press Tel. (212) 570-3633 Fax (212) 570-4169 [email protected] NOSTALGIA, BY BUCKSBAUM AWARD-WINNER OMER FAST, RECEIVES NEW YORK DEBUT AT THE WHITNEY Nostalgia III (production still), 2009 Super 16mm film transferred to high-definition video, color, sound; 32:48 minutes Photograph by Thierry Bal; courtesy gb agency, Paris; Postmasters, New York; and Arratia, Beer, Berlin. NEW YORK, November 18, 2009 – Omer Fast: Nostalgia is a new three-part film and video installation that continues Fast's fascination with exploring configurations of fact and fiction through narrative and filmic constructions, intertwining modes of documentary and dramatization. In this exhibition, organized by Tina Kukielski, senior curatorial assistant, the work receives its New York debut at the Whitney Museum of American Art, where it will be seen from December 10, 2009, through February 14, 2010. It is presented as part of the 2008 Bucksbaum Award, conferred on Fast for significant contributions to the visual arts in the United States. Endowed by Whitney Trustee Melva Bucksbaum and her family, the Bucksbaum Award is given every two years to an artist chosen from the Museum’s Biennial exhibition. (The next recipient will be selected from among the artists in the 2010 Whitney Biennial, which opens to the public on February 25.) Nostalgia (2009) begins with a fragment from an interview between the artist and an African refugee seeking asylum in London, during which the artist/interviewer is told how the refugee built a trap for catching a partridge back home in his native Nigeria. -

Translation in the Work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2007 (Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast Kelli Bodle Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Bodle, Kelli, "(Mis)translation in the work of Omer Fast" (2007). LSU Master's Theses. 4069. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (MIS)TRANSLATION IN THE WORK OF OMER FAST A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The School of Art by Kelli Bodle B.A., Michigan State University, 2002 August 2007 Table of Contents Abstract……...……………………………………………………………………………iii Chapter 1 Documentary and Alienation: Why Omer Fast’s Style Choice and Technique Aid Him in the Creation of a Critical Audience……………………………… 1 2 Postmodern Theory: What Aspects Does Fast Use to Engage Audiences and How Are They Revealed in His Work……………………………………….13 3 Omer Fast as Part of a Media Critique……………………….………………31 4 Artists and Ethics……………….……………………………………………39 5 (Dis)Appearance of Ethics in Omer Fast’s Videos..…………………………53 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..64 Vita...……………………………………………………………………………………..69 ii Abstract For the majority of people, video art does not have a major impact on their daily lives. -

Jesper Just Biography

JESPER JUST BIOGRAPHY Jesper Just Born in 1974 in Copenhagen, Denmark. Lives and works in New York EDUCATION 1997-2003 The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. REPRESENTED BY Galleri Nicolai Wallner, Copenhagen Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris James Cohan Gallery, New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2011 ––– This Nameless Spectacle, MAC/VAL, Vitry-sur-Seine, France A Vicious Undertow, Single-Chanel Series, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA, USA John Curtin Gallery, Perth, Australia This Nameless Spectacle, BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK Photo Spring, Beijing, China MAP, Mobile Art Production, Stockholm, Sweden Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, Montréal, Canada 2010 ––– ARTscape: Denmark – Jesper Just, Galerija VARTAI, Vilnius, Lithuania Jesper Just: Romantic Delusions, Tampa Museum of Art, Tampa, FL, USA 2009 ––– Invitation to Love, Kunstnernes Hus, Oslo, Norway Jesper Just, Centro de Arte Moderna José de Azeredo Perdigão - Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal Tromsø Gallery of Contemporary Art, Norway 2008 ––– Romantic Delusions, Galerie Emmanuel Perrotin, Paris, France Romantic Delusions, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, NY, USA Romantic Delusions, U-turn / Kunsthallen Nikolaj, Copenhagen, Denmark A Voyage in Dwelling, Victoria Miro Gallery, London, England Jesper Just, La Casa Encendida, Madrid, Spain 2007 ––– A Vicious Undertow, Perry Rubenstein Gallery, New York Jesper Just, Kunsthalle Wien (Museumsquartier), Vienna Jesper Just, SMAK Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Gent Belgium Jesper Just, Witte de With Center -

Omer Fast Nostalgia Scoring the Continuity and Discontinuity of Their Shared Narratives

the trap to reveal this interview as staged. There is a productive confusion when we notice the details, how this video is too perfect—the quality that mimics television, not documentary; the multiple camera angles and edits that belie the construction of the footage; the seamlessness of the dialogue. And so it turns on itself to reveal both interior and exterior narratives, articulating the fact that this work narrates the story it tells at the same time as it narrates its own making. The spatialization of Fast’s multipart installations highlights this self-reflexivity, under- omer fast nostalgia scoring the continuity and discontinuity of their shared narratives. The multiplicity of filmic tropes—the documentary, the reenactment, the docudrama, the melodrama— It starts with a trap. Omer Fast, the filmmaker, interviews his subject, a refugee from allows for the mechanics of structured scripting, exacting editing, and looping to the Niger Delta who is seeking asylum in Britain. The man speaks of his experiences become explicit. The physical experience of viewing, of watching and listening, and as a child soldier surviving under difficult conditions, and ultimately tells a rather making connections between constituent parts is crucial to the exercise of creating banal story of building a trap for partridges, a craft taught to him by an ex-soldier Omer Fast: Still from Nostalgia III, 2009; Super 16mm film transferred to HD video; courtesy of the artist; an aggregate awareness of the effects of narrative and image construction. The work gb agency, Paris; Postmasters, New York; and Arratia, Beer, Berlin. in his homeland. -

The Power Plant Presents and Evening with Artist Omer Fast Tuesday, 11 September, 7 PM at the Studio Theatre, Harbourfront Centre, 235 Queens Quay West, Toronto

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 6 SEPTEMBER 2012 The Power Plant presents and evening with artist Omer Fast Tuesday, 11 September, 7 PM at the Studio Theatre, Harbourfront Centre, 235 Queens Quay West, Toronto The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery presents artist Omer Fast as part of its ongoing International Lecture Series, which brings world-renowned artists, curators and critics to Toronto, and is supported this year by the J.P. Bickell Foundation. Omer Fast (born 1972, Jerusalem) lives and works in Berlin. He will speak about his acclaimed art practice in conjunction with solo exhibition at The Power Plant, Continuous Coverage, opening 14 September. Fast received his BA from Tufts University (1995) and his MFA from Hunter College (2000). He was the recipient of the 2009 Preis der Nationalgalerie für Junge Kunst and the 2008 Bucksbaum Award, among other honours. Fast has had solo exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus (2012); Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2010); Berkeley Art Museum (2009); and Museum of Modern Art, Vienna (2007). His work has also been featured in dOCUMENTA (13) Kassel (2012) and numerous biennials and group exhibitions. His work is represented by gb agency, Paris and ARRATIA, BEER, Berlin. Ticket Information FREE Members, $12 Non-Members Visit thepowerplant.org or call the Harbourfront Centre Box Office at 416.973.4000 to purchase tickets. Please note that if an event is sold out, reserved Members’ tickets that are not picked up by 6:50 PM will be released. Members are invited to bring a guest for FREE. Please call 416.973.4926 to reserve these tickets or to become a Member of The Power Plant. -

As Verbal Communication Is Becoming Less and Less Trustworthy

As verbal communication is becoming less and less trustworthy – and one could say, purposely and progressively emptied out of meaning through politics and mass media – we search for meanings that lie elsewhere. How can we free ourselves from set definitions enforced by spoken language’s power structures? Beyond words, we find plenty of other forms of communication, such as sound, tone, gesture, movement, rhythm, resonance and the repetition of all of the above. They are essential to how we go through the world, arranging the space between ourselves and our others – our boundaries become relational, they touch and intersect. Such ways of sensing and describing our circumstances become essential parts of our identities. This is how we relate to our surroundings, how we define ourselves in the eyes of others as well as to ourselves, thinking about the permeability of borders such as our skin. With A Gesture Towards Transformation, the gallery spaces become a territory encoding a multiplicity of identities and geographies, constantly shifting and moving. Expanding the idea of the present, the works were conceived and enacted at various historical moments over the last two decades, and yet remain viscerally relevant to our current times. Carrying the potential for transformation and activism, rather than being directly reactionary to contemporary politics, they build a new language and meaning bottom up, and through their own logic. Rather than creating utopian or parallel circumstances, the works exist in this reality and articulate empowering statements. Aimar Arriola (b 1976 Markina-Xemein, Basque Country, Spain) works as an independent researcher, curator and editor based in London and Basque Country. -

Omer Fast. Der Oylem Iz a Goylem July 26 – October 6, 2019

Omer Fast, Der oylem is a goylem, 2019, courtesy of the artist Omer Fast. Der oylem iz a goylem July 26 – October 6, 2019 Press conference: Fr, July 26, 11am Artist Talk with Omer Fast: Fr, July 26, 7pm Opening: Fr, July 26, 8pm An exhibition of new work by Omer Fast, including a new film commissioned by the Salzburger Kunstverein. Known for films that blend fictional and documentary processes, Fast has recently expanded his work to include architectural interventions and theatrical mise-en-scènes that explore social issues and political topics. His new film, Der oylem iz a goylem, was shot in March, 2019 in Salzburg and will premiere on July 26, 2019 at the Salzburger Kunstverein. The Exhibition This exhibition includes three films installed in a theatrical mise-en-scène designed by the artist. The first film, Der oylem iz a goylem, depicts two characters who are stuck on a chair lift, high above the wooded ski slopes of a snowy mountain resort. The second film, The Invisible Hand, follows a family’s ordeals in a forest and dense city in the Pearl River Delta, China. The third film, August, is loosely based on the final years of German photographer August Sander. Although worlds apart and speaking different languages, the first two films nevertheless evolve from the same medieval fairytale. Visitors will be presented with two case studies, seemingly distinct but sharing a common past and exhibiting similar symptoms. The film August will be installed separately in an autonomous gallery. Installation 1 Der oylem iz a goylem Single Channel Film, produced for the exhibition Based on a medieval Jewish fairytale, this film takes place on a chair lift, high above the wooded ski slopes of a snowy mountain resort in the Austrian Alps. -

Christian Marclay: the Clock and Omer Fast: Continuous Coverage with a FREE Opening Party on Friday, 14 September, 2012

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 27 AUGUST 2012 The Power Plant opens two ground-breaking exhibitions Christian Marclay: The Clock and Omer Fast: Continuous Coverage with a FREE opening party on Friday, 14 September, 2012 The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery’s Fall 2012 season opens with two outstanding exhibitions featuring the work of award-winning artists Christian Marclay and Omer Fast. Christian Marclay’s The Clock has been called “a masterpiece of our time.” Since premiering in London in 2010, the work has drawn thousands to art venues around the world who have lined up to see this critically-acclaimed, 24-hour montage of film and television. The Power Plant is pleased to present The Clock to Toronto audiences for the first time. Narrative structures and constructions involving film and the media also concern Omer Fast, whose most recent work Continuity, featured in dOCUMENTA (13) 2012, will be included in this captivating solo exhibition. The Power Plant opens both exhibitions FREE to the public as part of the year- long celebration of the gallery’s 25th anniversary. Join us for a FREE Opening Party for all on Friday, 14 September, 2012 from 5 – 11 PM. Be one of the first to see the new exhibitions and meet artist Omer Fast. A public tour of the exhibitions with Director of The Power Plant Gaëtane Verna and guest-curator Melanie O’Brian will begin at 6:15 PM. JK Frites, Fidel Gastro, and Ezra’s Pound will be onsite to tempt all taste buds and a cash bar will be available. Christian Marclay: The Clock 15 September – 25 November, 2012 The Clock (2010) is a unique and compelling work created by world-renowned sound and video artist Christian Marclay (born 1955, California). -

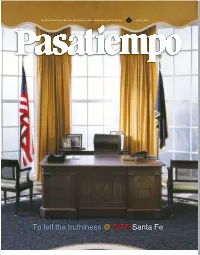

Spielberg's List

The New Mexican’s Weekly Magazine of Arts, Entertainment & Culture July 6, 2012 To tell the truthiness @ SITE Santa Fe he term “truthiness” was presented by comedian Stephen Colbert on his television program The Colbert Report in 2005 to refer to situations we believe to be true or want to be true, whether or not they are factual. Colbert used the word in reference to statements made during the presidency of George W. Bush such as the justifications given to launch T preemptive strikes against Iraq. The Bush administration’s reasons Michael Abatemarco I The New Mexican ranged from Iraq’s possible harboring of terrorists suspected of collaborating in the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks to the belief that Iraq was manufacturing weapons of mass destruction. Today, truthiness can refer to a more nebulous, although common, aspect of our day-to-day lives: belief in the veracity of our convictions, leaving little room for critical thinking. In More Real? Art in the Age of Tr uthiness, Elizabeth Armstrong, contemporary art curator at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, has pieced together an exhibition, in To tell the collaboration with SITE Santa Fe, establishing truthiness as an artistic concern and a global phenomenon. While More Real? is not intended to replace SITE’s biennial, it was developed at the level of previous SITE biennials in terms of its international scope and its quality. Architect Greg Lynn was hired to design a new facade for the space. More Real? has its first run at SITE, and the show travels to truthiness the Minneapolis Institute of Arts in March 2013. -

Adam Broomberg

ADAM BROOMBERG Born 1970 in Johannesburg, South Africa Lives and works in Berlin, Germany SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Blood in the Cut (forthcoming), signs and symbols, New York, New York 2020 Bureaucracy of Angels (online), signs and symbols, New York, New York 2019 Rudiments, A4 Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa Seenfifteen, London, UK WOE FROM WIT, Synthesis Gallery, Berlin, Germany 2018 Fig-futures, WEEK 3 / Broomberg & Chanarin, Kettles Yard, Cambridge, UK Bandage the knife, not the wound, Nogueras Blanchard Gallery, Madrid, Spain Bandage the knife, not the wound, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa Broomberg & Chanarin: Divine Violence, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France 2017 Not For Publication And Sale In Iran, Ag Galerie, Tehran, Iran The Bureaucracy of Angels (commission), Kings Cross St. Pancras, Art on the Underground – TFL, London, UK Trace Evidence, Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy 2016 Dont Start With The Good Old Things But The Bad New Ones, C/O Berlin, Berlin, Germany; traveled to Hasselblad Foundation, Gothenburg, Sweden Rudiments, Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland Art on the Underground, Stratford, London, UK 2015 Every piece of dust on Freuds couch, Freud Museum, London Rudiments, Lisson Gallery, London People in Trouble Laughing Pushed to the Ground, Belfast Exposed, Belfast, UK To Photograph the Details of a Dark Horse in Low Light, Foam Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam, Netherlands Divine Violence, Goodman Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa Rudiments, Centre for Contemporary Art, Ujazdowski Castle, -

Codes and Modes Conference Program

CODES AND MODES HUNTER COLLEGE, CUNY 1 CODES AND MODES The Character of Documentary Culture November 07 - 09, 2014 Integrated Media Arts MFA Program Department of Film and Media Studies Hunter College, City University of New York Codes and Modes brings together scholars, makers, graduate students, and curators to interrogate the social spaces and formal and thematic boundaries within which contemporary documentary culture is produced. 2 LIST OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments 4 IMA Overview 6 The Reach of Documentary 7 Conference Schedule 15 Participants 30 Hunter College Floor Map 42 Food Recommendations 44 Resources 46 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Sponsored by: Integrated Media Arts MFA Program and the Department of Film and Media Studies Also supported in part by grants from: Arts Across the Curriculum, Hunter College and Auxiliary Enterprise Corporation, Hunter College Thank you: Jennifer J. Raab, President, Hunter College, Vita Rabinowitz, Provost and Vice President, Hunter College, Andrew Polsky, Acting Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences, Angela Haddad, Senior Associate Dean for Student Success, Luz Ramirez, Dean’s Office, and Professor Jay Roman, Chair of Film and Media Studies, Hunter College. Organized by Martin Lucas and Jason Fox Additional Support: Natalie Conn Aleksandra Gorbacheva Tom Gubernat Gayathri Iyer Peter Jackson Andrew Lund David Pavlovsky Kelly Spivey Claudia Zamora Program design by Baseera Khan 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS “Codes and Modes reflects the dynamism of the Integrated Media Arts (IMA) MFA Program. It resulted from the creativity, commitment, and collaboration so often on display here. Together, graduate faculty and students, unfazed by the obstacles inherent in mounting an inaugural conference of this scope, forged a compelling lineup that integrates artists, scholars, activists, and educators. -

Omer Fast 1972 Born in Jerusalem, Israël Lives and Works in Berlin

Omer Fast 1972 Born in Jerusalem, Israël Lives and works in Berlin, Germany Solo Exhibitions 2017 Talking is not always the solution, Martin-Gropius Bau, Berlin 2016 August, gb agency, Paris. Continuous Present , Baltic Center of Contemporary Arts, Gateshead. Omer Fast , James Cohan, New York. Omer Fast, Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin. Omer Fast, KUNSTEN Museum of Modern Art, Aalborg, DK 2015 Omer Fast , Taro Nasu Gallery, Tokyo, JP Omer Fast , Jeu de Paume, Paris, FR Omer Fast , Mocak, muzeum sztuki wspolczesnej, Krakow, PL 2014 5000 Feet, The Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, NL 2013 Everything That Rises Must Converge, gb agency, Paris, FR Everything That Rises Must Converge, Dvir Gallery, Tel Aviv, IL Omer Fast , The Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University,Waltham, MA Omer Fast , IMW, Imperial War Museum, London, UK Omer Fast , OK Centrum, Linz, AT Omer Fast , Moderna Museet, Stockholm, SE Continuity, Musée d’Art Contemporain, Montréal, CA Omer Fast , Arratia Beer, Berlin, DE 2012 Omer Fast , Herzliya Museum of Art, Herzliya, IL Omer Fast , Henie Onstad Art Center, Høvikodden, NO Continuous Coverage, The Power Plant,Toronto, CA Omer Fast , Five Thousand Feet is the Best, Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, US 2001/2011, Wexner Center for the Arts,The Ohio State University, Columbus, US 2011 Omer Fast , Model Art Center, Sligo, IE Omer Fast , Hordaland Art Centre, Bergen, NO Omer Fast , Kölnischer Kunstverein, Köln, DE Omer Fast , Netherlands Media Arts Institute, Amsterdam, NL Omer Fast , La Caixa, Barcelona, ES 2010 Omer Fast , gb agency, Paris, FR