Seabed-Mining-Tech-Review-2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vanuatu Stakeholder Consultation Workshop

Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) SPC-EU EDF10 Deep Sea Minerals Project Proceedings of the Vanuatu National Deep Sea Minerals Stakeholder Consultation Workshop Chantilly’s on the Bay, Port Vila, Vanuatu 16 May 2012 June 2012 SOPAC WORKSHOP REPORT (PR145) Hannah Lily1, Akuila Tawake1, Brooks Rakau2 1Deep Sea Minerals Project, Ocean and Islands Programme, SOPAC Division 2Vanuatu, Department of Geology, Mines and Water Resources A slide from Mr Tawake’s presentation about the Pacific’s Deep Sea Minerals potential This report may also be referred to as SPC SOPAC Division Published Report 145 Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) Private Mail Bag GPO Suva Fiji Islands Telephone: (679) 338 1377 Fax: (679) 337 0040 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.sopac.org SPC-EU EDF10 Deep Sea Minerals Project Proceedings of the Vanuatu National Deep Sea Minerals Stakeholder Consultation Workshop Chantilly’s on the Bay, Port Vila, Vanuatu 16 May 2012 SOPAC WORKSHOP REPORT (PR145) June 2012 Ocean and Islands Programme DISCLAIMER While care has been taken in the collection, analysis, and compilation of the information, it is supplied on the condition that the Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) of the Secretariat of Pacific Community shall not be liable for any loss or injury whatsoever arising from the use of the information. IMPORTANT NOTICE This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. [3] CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................................... 5 1. -

Down to Business

NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. Corporate Office 141 Adelaide Street West, Suite 1702 DOWN TO Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5H 3L5 www.nautilusminerals.com email: [email protected] BUSINESS Investor Relations Inquiries TSX: NUS 2010 ANNUAL REPORT AIM: NUS email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 Media Relations Inquiries email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. 2010 ANNUAL REPORT 65 CORPORATE INFORMATION Board of Directors Or write to: Geoff Loudon Chairman Computershare Investor Services Stephen Rogers President, CEO and Director 9th Floor, 100 University Avenue Toronto, ON M5J 2YI Canada David De Witt Director Inquiries in the United Kingdom: Down to Business Russell Debney Director Telephone: 0870.702.0003 Matthew Hammond Director Or write to: Cynthia Thomas* Director Computershare Investor Services plc John O’Reilly** Director PO Box 82, The Pavilions, Nautilus Minerals is leading the world in the development of the seafloor Officers and Management Bridgwater Road mineral resources industry. Over the past few years, the company has made Bristol BS997NH, United Kingdom great progress in the planning and design of its first project at Solwara 1 Stephen Rogers President and CEO in Papua New Guinea. In 2011, Nautilus is moving beyond the design Anthony O’Sullivan Chief Operating Officer Nominated Advisor and Broker (AIM) development phase, commencing construction of major pieces of equipment Shontel Norgate Chief Financial Officer and Corporate Secretary Numis -

Nautilus Minerals Annual Report 2015

NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. NAUTILUS MINERALS Corporate Office 141 Adelaide Street West, Suite 1702 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5H 3L5 www.nautilusminerals.com email: [email protected] Registered Office NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. 10th Floor, 595 Howe Street Vancouver, British Columbia Canada V6C 2T5 Investor Relations Inquiries TSX: NUS OTCQX: NUSMF OTC: NUSMF Nasdaq International Designation ANNUAL REPORT 2015 ANNUAL REPORT email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 +1 416 551 1100 Media Relations Inquiries email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 +1 416 551 1100 Building Momentum BUILDING MOMENTUM NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2015 CORPORATE INFORMATION 69 Corporate Information With the SPTs complete and the RALS including the SSLP due for delivery Board of Directors For Shareholder Accounts later in 2016, the final component of the seafloor production system, the Geoff Loudon, Chairman Inquiries in Canada: PSV, is the last key piece of equipment to be completed. Cutting steel for the Russell Debney, Director Telephone: 1.800.564.6253 (toll free in North America) PSV has commenced, block assembly is currently taking place and delivery Cynthia Thomas, Director International: +514.982.7555 is expected by the end of 2017. Seafloor mineral production at Solwara 1 is Dr. Mohammed Al Barwani, Director email: [email protected] gaining momentum as Nautilus looks to the first quarter of 2018 to be on Mark Horn, Director Inquiries in the U.S: the water and commencing operations in the Bismarck Sea of PNG. Tariq Al Barwani, Director U.S Investment bank Euro Pacific Capital Inc, serves as Nautilus Minerals’ Principal American Liaison (PAL) on Officers and Management the OTCQX and the NASDAQ International Designation (All acronyms and abbreviations can be found on page 26) Michael Johnston, President and Euro Pacific Capital, Inc. -

Precautionary Management of Deep Sea Minerals

Public Disclosure Authorized Precautionary Management of Deep Sea Minerals PACIFIC POSSIBLE BACKGROUND PAPER NO.2. Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Pacific Island countries face unique development challenges. They are far away from major markets, often with small populations spread across many islands and vast distances, and are at the forefront of climate change and its impacts. Because of this, much research has focused on the challenges and constraints faced by Pacific Island countries, and finding ways to respond to these. This paper is one part of the Pacific Possible series, which takes a positive focus, looking at genuinely transformative opportunities that exist for Pacific Island countries over the next 25 years and identifies the region’s biggest challenges that require urgent action. Realizing these opportunities will often require collaboration not only between Pacific Island Governments, but also with neighbouring countries on the Pacific Rim. The findings presented in Pacific Possible will provide governments and policy-makers with specific insights into what each area could mean for the economy, for employment, for government income and spending. To learn more, visit www.worldbank.org/PacificPossible, or join the conversation online with the hashtag #PacificPossible. © 2017 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: +1 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in the work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. -

Study to Investigate State of Knowledge of Deep Sea Mining

Study to investigate state of knowledge of deep sea mining Final report Annex 5 Ongoing and planned activity FWC MARE/2012/06 – SC E1/2013/04 Client: DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Rotterdam/Brussels, 28 August 2014 Study to investigate state of knowledge of deep sea mining Final report Annex 5 Ongoing and planned activity FWC MARE/2012/06 – SC E1/2013/04 Client: DG Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Brussels/Rotterdam, 28 August 2014 About Ecorys and Consortium Partners Consortium Lead Partner ECORYS Nederland BV P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 00 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] Registration no. 24316726 www.ecorys.com 2 BR27529 Table of contents List of abbrevations 4 1 Summary 7 2 Project licences overview 9 3 Project sheets 16 3.1 Projects located in The Area (projects 01-26) 16 3.2 Projects located in EEZs (projects 27- 52) 84 3.3 European Innovation Partnership commitments/projects 148 References 174 Study to investigate state of knowledge of deep sea mining 3 List of abbrevations ABNJ Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction AC Auxiliary Cutter Ag Silver ANU Australian National University APR Accounting Profits Royalty Au Gold AUV Autonomous Underwater Vehicle AVR Ad Valorem Royalty BC Bulk Cutter BGR Federal Institute for Geosciences and Natural Resources BMS Benthic Multi-coring System BMS Boring Machine System CCZ Clarion-Clipperton Fracture Zone CERENA Center for Natural Resources and the Environment CM Collecting Machine Co Cobalt COMRA China Ocean Mineral Resources Research and Development Association CSEM Controlled source electromagnetics CSIRO Australia's Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation Cu Copper CUT Clausthal University of Technology DEC Department of Environment and Conservation DORD Deep Ocean Resources Development Co. -

Nautilus Minerals Inc. Annual Report 2007

Nautilus MiNerals iNc. annual report 2007 Nautilus MiNerals a team committed to a new vision in mining 1.We have the ground • 365,000 km2 of tenement licences and exploration applications • Pipeline of opportunity for the harvesting of high-grade mineral deposits on the seafloor 2.the people • A team of more than 40 experienced professionals • Each dedicated to delivering the world’s first seafloor mine in 2010**Subject to permitting 3.the knowledge • Alliances with major technical, scientific and investment partners • Offering best-in-class project delivery and production method 4.the capital • US$310 million cash** in the bank • Well capitalized to continue exploration in 2008 and deliver Solwara 1 to production* *Subject to permitting **at December 31, 2007 5. a collaborative approach • Committed to advancing the science of mineral deposits on the seafloor by partnering with scientific institutions around the world • Actively working with local community organizations to ensure transparency and accountability contents letter to shareholders Pg. 2 Project Development update Pg. 8 exploration Overview Pg. 12 environmental update Pg. 16 Nautilus Cares Pg. 20 technical alliances Pg. 24 Management’s Discussion & analysis Pg. 29 Financial statements (in accordance with Canadian GaaP) Pg. 40 A COMMITTED TEAM AND A CLEAN SHEET OF PAPER 2007 was a year of significant progress and success for Nau- tilus Minerals inc. (“Nautilus”). Our exploration team discov- ered four new mineralized systems and registered a series of world firsts in remote Operated Vehicle (“rOV”) drilling, geophysics and the world’s first Ni 43-101 compliant resource estimate for a seafloor Massive sulphide (“sMs”) system. -

Annual Report 2014 Nautilus Minerals Inc

NAUTILUS MINERALS NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. ANNUAL REPORT 2014 NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. FORGING AHEAD Corporate Office 141 Adelaide Street West, Suite 1702 Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5H 3L5 ANNUAL REPORT 2014 ANNUAL REPORT www.nautilusminerals.com email: [email protected] Registered Office 10th Floor, 595 Howe Street Vancouver, British Columbia Canada V6C 2T5 Investor Relations Inquiries TSX: NUS OTCQX: NUSMF email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 +1 416 551 1100 Media Relations Inquiries email: [email protected] Tel: +61 7 3318 5555 +1 416 551 1100 FORGING AHEAD Corporate Information As the Seafloor Production Tools enter the Board of Directors commissioning phase and the Riser and Lifting System Geoff Loudon, Chairman For Shareholder Accounts Russell Debney, Director is nearing completion, the final component of Nautilus Inquiries in Canada: Cynthia Thomas, Director Telephone: 1.800.564.6253 (toll free in Minerals’ Seafloor Production System, the Production Dr. Mohammed Al Barwani, Director North America) International: +514.982.7555 Support Vessel (PSV), is on the horizon. With steel Usama Barwani, Director email: [email protected] cutting for the PSV scheduled for the second half Mark Horn, Director Inquiries in the U.S: Officers and Management U.S Investment bank Cowen and Company, serves of 2015, the Company is “Forging Ahead” with its as Nautilus Minerals’ Principal American Liaison Michael Johnston, President and (PAL) on the OTCQX International. seafloor copper-gold project at Solwara 1 and its goal Chief Executive Officer Cowen and Company Shontel Norgate, Chief Financial Officer to make deep sea mining a viable and sustainable 599 Lexington Avenue Kevin Cain, VP Projects New York, NY 10022 email: [email protected] alternative source to satisfy the world’s demand for Jonathan Lowe, VP Strategic Development much needed minerals. -

Resource Roulette – How Deep Sea

This report benefitted greatly from the assistance of many people on the ground, including numerous experts and partners across the Pacific. We are especially grateful to all those representatives of government, industry, civil society, academia, think- tanks, customary landowners, and other concerned citizens with whom we met during our case study fieldwork carried out in Tonga, Papua New Guinea, and Fiji, many of whom provided us with helpful insights and legislative and other material on deep sea mining, as well as feedback on the report itself. We would also like to thank our partners at Brot für die Welt (Bread for the World), particularly Ulla Kroog and Francisco Mari, for their invaluable role in conceptualizing and supporting this work. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................... i 2 METHODOLOGY ................................................................................ 1 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 4 POLICY DISCUSSION ......................................................................... 2 4.1 Big Ocean States ............................................................ 2 4.2 DSM Overview ................................................................ 2 4.3 European Union Interest ............................................... 3 4.4 SPC’s Position ................................................................. 3 4.5 Risks, Uncertainties, and Impacts of DSM .................... 4 -

Rosembaum, Helen. out of Our Depth

OCTOBER 2011 OUT OF OUR DEPTH Mining the Ocean Floor in Papua New Guinea October 2011 Author: Helen Rosenbaum (PhD) Researcher: Anne Nolan Editors: Natalie Lowrey, Christina Hill (Oxfam Australia) and Catherine Coumans (PhD) (Mining Watch Canada) Expert contributions: Alex Rogers, Professor, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford; Scientific Director of the International Programme on State of the Ocean Jeff Kinch, Principal, PNG National Fisheries College, New Ireland Province, PNG Stuart Kirsch, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, The University of Michigan With support from: MiningWatch Canada www.miningwatch.ca CELCoR [The Centre for Environmental Law and Community Rights Papua New Guinea] Oxfam Australia www.oxfam.org.au The Packard Foundation www.packard.org Design, layout and illustrations: Natalie Lowrey Cover image: Montage by Natalie Lowrey, photos courtesy of Jessie Boylan/MPI and the University of Bremen. Back cover: Children playing in Kavieng, Papua New Guinea. Photo: Jessie Boylan/MPI CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. DEEP SEA MINERAL RESOURCES 7 2.1 The Formation of Seabed Mineral Resources at Hydrothermal Vents 7 2.2 The Location of Sea-floor Massive Sulphides 9 2.3 Mineral Deposits in the Manus Basin 10 3. THE UNIQUE ECOLOGY OF HYDROTHERMAL VENTS 11 4. NAUTILUS MINERALS INC. 12 4.1 The Scope of Nautilus’ Exploration 12 4.2 The Financial Position of Nautilus 13 4.3 The Status of the Solwara 1 Project 13 4.4 The Mining Process 14 5. ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT OF SOLWARA 1 16 5.1 The Environmental Approvals Process 16 5.2 Inadequate Risk Analysis 16 5.3 The Environmental Management Plan 17 6. -

Accountability Zero: a Critique of Nautilus Minerals Environmental

A CRITIQUE OF THE NAUTILUS MINERALS ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL BENCHMARKING ANALYSIS OF THE SOLWARA 1 PROJECT accountability ZERO Authors: Helen Rosenbaum, DSM Campaign Francis Grey, Economists@Large The Deep Sea Mining (DSM) Campaign is an association of non-governmental and community based organisations and citizens from the Pacific Rim Region who are concerned about the impacts of DSM on marine and coastal ecosystems and human communities. As an emerging threat, DSM has not been widely discussed beyond mining and technical circles. A key aim of the DSM campaign is to raise the profile of issues amongst government and the general populace. We seek to generate critical thinking and thus informed debate about the risks and costs of this new mining industry. We have produced several articles, fact sheets, two science-based reports, made a submission to the International Seabed Authority, conducted advocacy and participated in discussions on DSM at international, Pacific regional and national levels. All materials and resources are downloadable at our web site. The Deep Sea Mining Campaign is a project of The Ocean Foundation Established in 1989, Economists at Large are a team of economists working to create a sustainable economy, society and environment. We are like ‘economists without borders’, working where economics is least represented, using the tools of economic analysis to ensure the true value of the environment and society is fully recognised. We work frequently with the not-for-profit sector, applying the tools of economics to natural resource management, environmental conservation, animal welfare tourism and general public policy analysis. Francis Grey is the founder and has worked as an advisor or author on a range of projects and papers investigating cost-benefit analysis, environmental valuation and sustainability, tourism, major developments and natural resources. -

Why-Rush.Pdf

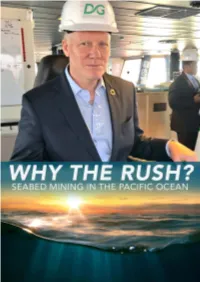

Mining Watch Canada | Deep Sea Mining Campaign | London Mining Network JULY 2019 FRONT COVER: Secretary General of the United Nation’s International Seabed Authority, Michael Lodge, dons a ‘DeepGreen’ hard- hat. Lending his position to promote DeepGreen’s commercial interests calls into question the ISA’s capacity to serve the interests of its member states and the environment it is mandated to protect. Image source: https://twitter.com/mwlodge/status/984626856384221185 CONTENTS Acronyms Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1 1. Seabed mining in the Pacific: A speculative frontier ............................................................. 4 2. Why the rush? ............................................................................................................................ 6 Frontier investors and their institutional backers promoting seabed mining in the Pacific Ocean 2.1 Nautilus and DeepGreen: Miners of Markets and Profit ....................................... 6 2.1.1 Rags to Riches for Frontier Investors ..................................................................... 7 2.2 The role of the Pacific Community (SPC) ................................................................. 11 2.3 Interesting Bedfellows: DeepGreen and Nauru ..................................................... 13 2.4 The International Seabed Authority - regulating in whose interests? ................. 14 2.4.1 The ISA Compromised by Corporate Agendas -

SPC-EU EDF10 Deep Sea Minerals Project

Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) SPC-EU EDF10 Deep Sea Minerals Project Proceedings of the Solomon Islands National Deep Sea Minerals Stakeholder Consultation Workshop, Horticulture Centre Conference Room, Hyundai Mall, Honiara, Solomon Islands 23 May 2012 January 2013 SOPAC WORKSHOP REPORT (PR151) Hannah Lily1, Akuila Tawake1, Joseph Ishmael2 1Deep Sea Minerals Project, Ocean and Islands Programme, SOPAC Division 2Ministry of Mines, Energy and Rural Electrification A slide from Mr Tawake’s presentation about the Pacific’s deep sea minerals potential This report may also be referred to as SPC SOPAC Division Published Report 151 Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) Private Mail Bag GPO Suva Fiji Islands Telephone: (679) 338 1377 Fax: (679) 337 0040 E-mail: [email protected] Web site: http://www.sopac.org SPC-EU EDF10 Deep Sea Minerals Project Proceedings of the Solomon Islands National Deep Sea Minerals Stakeholder Consultation Workshop Horticulture Centre Conference Room, Hyundai Mall, Honiara 23 May 2012 SOPAC WORKSHOP REPORT (PR151) January 2013 Ocean and Islands Programme DISCLAIMER While care has been taken in the collection, analysis, and compilation of the information, it is supplied on the condition that the Applied Geoscience and Technology Division (SOPAC) of the Secretariat of Pacific Community shall not be liable for any loss or injury whatsoever arising from the use of the information. IMPORTANT NOTICE This report has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Union. [3] CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................................