The Story of a Traumatic Encounter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gentle Extermination » of the Mentally III in Psychiatrie Hospitals in France

Violence in the Blind Spot Xavier Godinot Xavier Godinot has been a full-time member of the International Movement A TD Fourth World volunteer corps since 1974. With a Ph.D. in Labour Economies, he has tirelessly fought for the poorest people's rightfully place in the world of work. After leading a pilot project on professional insertion and qualification in the Rhone-Alps region of France, he wrote, in partnership with Fourth World activists, scholars and members of the business community, a book evaluating this project and giving proposais for further action. This book, On voudrait connaitre le secret du travail has been summarised in English under the title, Finding Worke : Tell Us the Secret. Currently in Brussels, Mr. Godinot now heads the International Movement A TD Fourth World's Institute for Research and Training in Human Relations Long-term acts of violence against very poor population groups are occasionally reported in newspapers. They are the culmination of everyday acts of violence against the poor, and are more serious than often acknowledged. ln the recent Final Report on Human Rights and Extreme poverty1, Leandro Despouy writes, « Extreme poverty involves the denial, not of a single right or a category of rights, but of human rights as a whole. [...It] is a violation not only of economic and social rig, hts as is generally assumed from an economic standpoint, but also, and to an equal degree, of civil, political and cultural rights... » The effect on the lives of those stricken by extreme poverty « has a precise and clearly defined name in standard legal terminology: absolute denial of the most fundamental human rights. -

Ilan Eshkeri

ILAN ESHKERI AWARDS AND NOMINATIONS BRITISH ACADEMY GAMES AWARDS Ghost of Tsushima NOMINATION (2021) Music DICE AWARDS NOMINATION (2021) Ghost of Tsushima Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition INTERNATIONAL FILM-MUSIC Ghost of Tsushima CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2020) Best Original Score for a Video Game or Interactive Media SCL AWARDS NOMINATION (2021) Ghost of Tsushima Outstanding Original Score for Interactive Media MUSIC IN VISUAL MEDIA AWARD Ghost of Tsushima (2020) Outstanding Score – Video Game MUSIC IN VISUAL MEDIA AWARD “The Way of the Ghost" from Ghost of (2020) Tsushima Outstanding Song – Video Game HOLLYWOOD MUSIC IN MEDIA “Feels Like Summer” from SHAUN THE NOMINATION (2015) SHEEP Song-Animated Film *shared INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC STARDUST CRITICS ASSOCIATION AWARD (2007) Breakout Composer of the Year INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC STARDUST CRITICS ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2007) Best Original Score-Fantasy/Science Fiction WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD HANNIBAL RISING NOMINATION (2007) Discovery Of The Year WORLD SOUNDTRACK AWARD LAYER CAKE NOMINATION (2004) Discovery Of The Year The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency, Inc. (818) 260-8500 1 ILAN ESHKERI FEATURE FILM FARMING Francois Ivernel, Andrew Levitas, Miranda Groundswell Productions Ballestros, Michael London, Charles de Rosen, Charles Steel, Janice Williams, James Wilson, prods. Adewale Akinnouoye-Agbaje, dir. THE WHITE CROW Carolyn Marks Blackwood, Ralph Fiennes, Sony Pictures Classics Francois Ivernel, Andrew Levitas, Gabrielle Tana, prods. Ralph Fiennes, dir. SWALLOWS AND AMAZONS Nick Barton, Nick O’Hagan, Joe Oppenheimer, Orion Pictures prod. Philippa Lowthorpe dir. THE EXCEPTION Judith Tossell, Bill Haber, Jim Seibel, prods. Egoli Tossell Film David Leveaux, dir. MEASURE OF A MAN Christian Taylor, prod. Great Point Media Jim Loach, dir. -

Ex-Gratia Payment Scheme for Former British Child Migrants

EX-GRATIA PAYMENT SCHEME FOR FORMER BRITISH CHILD MIGRANTS: Introduction The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) Interim Report and its report on Child Migration Programmes were both published in Spring 2018. The Inquiry recommended that the UK Government establish a financial redress scheme for surviving former British child migrants on the basis that they were exposed to the risk of sexual abuse. On 19th December the Government published its response to the Inquiry. The response announced that the Government would establish an ex-gratia payment scheme for former British child migrants, in recognition of the fundamentally flawed nature of the historic child migration policy. This note provides further detail of the payment scheme. Aim: The payment is being made in recognition of the exceptional and specific nature of the historic Child Migration Policy. It is payable to all former British child migrants, regardless of whether they suffered abuse, in recognition of the fundamentally flawed nature of the historic Child Migration Programmes and in line with the recommendation in IICSA’s report. Eligibility: The scheme is open to any former British child migrant who was alive on 1 March 2018, or the beneficiaries of any former child migrant who was alive on 1 March 2018 and has since passed away. The ex-gratia payment will be payable to all applicants regardless of their individual circumstances, including the receipt of payments received from other Governments or through private legal action. Conditions: The claimant must have been a child migrant sent from the United Kingdom and Crown Dependencies (England, Wales, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Channel Islands and the Isle of Man). -

David Pimm Director of Photography

David Pimm Director of Photography www.davidpimm.com Film & Television Director Production Co Producers RAGDOLL Toby Macdonald Sid Gentle Films Lizzie Rusbridger MY NAME IS LEON Lynette Linton Douglas Road Carol Harding Productions BOXING DAY Aml Ameen Film 4 Joy Gharoro-Akpojotor BFI Damian Jones PANDEMONIUM Ella Jones BBC Studios Tom Jordan Pilot SAVE ME TOO Jim Loach World Productions Lizzie Rusbridger Winner: BAFTA, Best Drama, 2021 Coky Giedroyc Sky Atlantic GET HAPPY Simon Amstell Tiger Aspect Katie Churchill Taster Pippa Brown URBAN MYTH: MADONNA & BASQUIAT Adam Wimpenny Wild Card Films Adam Morane-Griffiths Sarah Solemani Joe Hill BENJAMIN Simon Amstell Open Palm Pictures Louise Simpson Official Selection: London Film Festival, 2018 Alexandra Breede LOVE ME NOT Alexandros Avranas Faliro House Productions Christos V. Official Selection: San Sebastian, 2017 Les Films Du Lendemain Konstantakopoulos Lelia Andronikou LADY MACBETH William Oldroyd Sixty Six Pictures Fodhla Cronin O'Reilly Additional Photography IFeatures SHIELD 5 Anthony Wilcox Lorton Entertainment Mark Hopkins Web Series Declan Reddington Choice Award, Raindance, 2016 Selected Short Films TONI WITH AN I Marco Alessi BBC Films Ksenia Harwood Nomination, BAFTA, Short Film, 2020 Official selection: Berlin, 2020 SARAH CHONG IS GOING TO KILL HERSELF Ella Jones Creative England Alexandra Blue Official Selection: Loco Film Festival, 2016 Big Talk Productions PATRIOT Eva Riley NFTS Michelangelo Fano Nomination: Cannes Film Festival, 2015 Official Selection: Telluride Film Festival, 2015 OUT OF SIGHT Nick Rowland NFTS Nick Rowland Official Selection: Sundance, 2015 Commercial credits include: SNAPPY SHOPPER/Greenroom/Richard Pengelly SCOTTISH POWER GOGGLEBOX IDENTS/Greenroom/Richard Pengelly KIA/Recipe/Michael O Kelly AXA/Recipe/Michael O Kelly Xero/Brave Spark/Michal J. -

To Stick Distinct Tranquillity

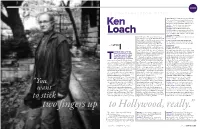

0123456789 THE EMPIRE INTERVIEW IN CONVERSATION WITH explosion and you’re the director, you get special effects in and they make it explode and you just choose the camera positions. It’s much harder to do a good scene in a council flat than it is to blow up a car — from the director’s point of view. Ken EMPIRE: Because in a flat you don’t have anything to rely on but faces and emotion? LOACH: And quite a constricting location. From the directing point of view, the endless chases and Loach technical stuff are quite tedious, because they all take a hugely long time. showed the ’60s could be sour as well as Swinging — EMPIRE: So that wasn’t the part that was the most to the Palme d’Or-winning The Wind That Shakes The engaging for you… Barley (2006), which deals with the sensitive politics LOACH: It was the easiest part, in some ways. of Ireland’s partition within a gripping combat The difficult part was deciding whether this was context and a touching family tragedy. Even in his the right film to make about war, and about this Words: Nev Pierce Portrait: Mitch Jenkins lesser features it’s rare to find moments that don’t particular war. feel true. Famously, he films everything in sequence, EMPIRE: Why difficult? handing screenplay pages to actors only a day or so in LOACH: Well, because we’re still quite close to advance, so they discover their character’s journey as the actual event of it. And to do something about HE PENSIONER WITH THE the production progresses. -

Director: Harry Wootliff Producers: Tristan Goligher, Valentina Brazzini, Ben Jackson, Ruth Wilson and Jude Law

Kahleen Crawford Casting: As casting directors (selected credits) True Things About Me (2020) Director: Harry Wootliff Producers: Tristan Goligher, Valentina Brazzini, Ben Jackson, Ruth Wilson and Jude Law. Feature film. Cast inc: Ruth Wilson, Tom Brooke and Hayley Squires Vigil (2020) Directors: James Strong, Isabelle Sieb Producer: Angie Daniell, Simon Heath and Jake Lushington, World Productions. 6 part Television series. Cast inc: Suranne Jones, Rose Leslie, Shaun Evans, Paterson Joseph and Gary Lewis His Dark Materials S1 and S2 (2019-Present) Directors inc: Tom Hooper. Producers: Jane Tranter and Julie Gardner, Bad Wolf, Dan McCulloch and Laurie Borg. BBC TV series based upon the Philip Pullman books, adapted by Jack Thorne. Currently casting. Cast inc: Ruth Wilson, James McAvoy, Dafne Keen, Amir Wilson, Andrew Scott, Simone Kirby and Lin-Manuel Miranda The Nest (2020) Directors: Andy De Emmony, Simen Elsvick Producers: Clare Kerr, Susan Hogg, Simon Lewis, Studio Lambert Television series Cast inc: Martin Compston, Sophie Rundle and Mirren Mack The North Water (2020) Director: Andrew Haigh Producers: Iain Canning, Jamie Laurenson and Kate Ogborn, See-Saw. BBC Television. Cast inc: Colin Farrell, Jack O’Connell, Stephen Graham and Tom Courtenay I Hate Suzie (2020) Directors: Georgi Banks-Davies and Anthony Neilson Produces: Andrea Dewsbery and Julie Gardner. 8-part Television series for Sky Atlantic created by Billie Piper and Lucy Prebble, written by Lucy Prebble. Cast inc: Billie Piper, Laila Farzad, Dan Ings, and introducing Matthew -

FT Prog 27:FT Prog Print

Thu 26 May (1 day only) 7.45pm Booking The Box Office is open at 7pm on days when there is a charge for (PG) BENDA BILILI! admission. A joyous documentary giving insight into the story Seat prices are now £5 (full price) and £3.50 (concessions). Numbered of Staff Benda Bilili, a group seats may be reserved in advance but they may not be collected or of seven Congolese paid for in advance. musicians, most of whom Season tickets for the films in this programme are £40.00 (full price) have physical disabilities. and £30.00 (concessions). Renaud Barret and Florent de La Tullaye’s film follows Carers accompanying disabled customers to the Film Theatre will be the band’s progress over admitted free of charge. Stoke on Trent’s Independent Cinema four years, from the poverty Telephone reservations may be made at any time on our answering stricken streets of Kinshasa machine 01782 411188. Please call before 2pm for same day to international tours. Benda Bilili! is a truly reservations. Please speak clearly, stating the film title, date and time, heartwarming celebration your name and a phone number in case there is any query. We will of triumph over adversity, reserve the best available seats. If you prefer to speak to us in person, accompanied by their exuberant blend of blues and African rumba. phone between 12.30 and 1.30 pm, Mon, Tue, Thu and Fri (not Wed). Democratic Republic of Congo/France (subtitled), 2010, 88 mins Reserved tickets must be claimed 20 minutes before the performance. -

Brown to Apologise to Care Home Children Sent to Australia and Canada

UNIVERSITÉ MONTPELLIER III – PAUL-VALÉRY DÉPARTEMENT D’ÉTUDES ANGLOPHONES MARDI 24 NOVEMBRE 2009 – F108 – 15h15 Enseignant : Frédéric Delord ÉPREUVE D’ANGLAIS POUR NON-SPÉCIALISTES W19AN1 – MASTER 1 – OPTION 2 EXAMEN FINAL Aucun document autorisé (Sauf étudiants étrangers : dictionnaire bilingue langue maternelle-français) Durée de l’épreuve : 2 heures Sujet : RÉDIGEZ EN FRANÇAIS UNE SYNTHÈSE DES 3 TEXTES SUIVANTS : (450 à 550 mots) TEXT 1: Brown to apologise to care home children sent to Australia and Canada Children were cut off from families and some falsely told they were orphans in programme that sent 150,000 abroad between 1920 and 1967. Peter Walker, The Guardian , Monday 16 November 2009 Gordon Brown is to offer a formal apology to tens of thousands of British children forcibly sent to Commonwealth countries during the last century, many of whom faced abuse and a regime of unpaid labour rather than the better life they were promised. The prime minister plans to make the apology in the new year after discussions with charities representing former child migrants and their families, a Downing Street spokeswoman said today. In a letter to a Labour MP who has campaigned on the issue, Brown said that the "time is now right" for an apology, adding: "It is important that we take the time to listen to the voices of the survivors and victims of these misguided policies."Government records show that at least 150,000 children aged between three and 14 were taken abroad, mainly to Australia and Canada, in a programme that began in the 1920s and did not stop until 1967. -

Product Guide

AFM PRODUCTPRODUCTwww.thebusinessoffilmdaily.comGUIDEGUIDE AFM AT YOUR FINGERTIPS – THE PDA CULTURE IS HAPPENING! THE FUTURE US NOW SOURCE - SELECT - DOWNLOAD©ONLY WHAT YOU NEED! WHEN YOU NEED IT! GET IT! SEND IT! FILE IT!© DO YOUR PART TO COMBAT GLOBAL WARMING In 1983 The Business of Film innovated the concept of The PRODUCT GUIDE. • In 1990 we innovated and introduced 10 days before the major2010 markets the Pre-Market PRODUCT GUIDE that synced to the first generation of PDA’s - Information On The Go. • 2010: The Internet has rapidly changed the way the film business is conducted worldwide. BUYERS are buying for multiple platforms and need an ever wider selection of Product. R-W-C-B to be launched at AFM 2010 is created and designed specifically for BUYERS & ACQUISITION Executives to Source that needed Product. • The AFM 2010 PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is published below by regions Europe – North America - Rest Of The World, (alphabetically by company). • The Unabridged Comprehensive PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH contains over 3000 titles from 190 countries available to download to your PDA/iPhone/iPad@ http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/Europe.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/NorthAmerica.doc http://www.thebusinessoffilm.com/AFM2010ProductGuide/RestWorld.doc The Business of Film Daily OnLine Editions AFM. To better access filmed entertainment product@AFM. This PRODUCT GUIDE SEARCH is divided into three territories: Europe- North Amerca and the Rest of the World Territory:EUROPEDiaries”), Ruta Gedmintas, Oliver -

MD Program.Fm

Doctor of Medicine Program 24 Doctor of Medicine Program Mission Statement and the Medical Curriculum The mission of the Duke University School of Medicine is: To prepare students for excellence by first assuring the demonstration of defined core competencies. To complement the core curriculum with educational opportunities and advice regarding career planning which facilitates students to diversify their careers, from the physician-scientist to the primary care physician. To develop leaders for the twenty-first century in the research, education, and clinical practice of medicine. To develop and support educational programs and select and size a student body such that every student participates in a quality and relevant educational experi- ence. Physicians are facing profound changes in the need for understanding health, dis- ease, and the delivery of medical care changes which shape the vision of the medical school. These changes include: a broader scientific base for medical practice; a national crisis in the cost of health care; an increased number of career options for physicians yet the need for more generalists; an emphasis on career-long learning in investigative and clinical medicine; the necessity that physicians work cooperatively and effectively as leaders among other health care professionals; and the emergence of ethical issues not heretofore encountered by physicians. Medical educators must prepare physicians to respond to these changes.The most successful medical schools will position their stu- dents to take the lead addressing national health needs. Duke University School of Med- icine is prepared to meet this challenge by educating outstanding practitioners, physician scientists, and leaders. Continuing at the forefront of medical education requires more than educating Duke students in basic science, clinical research, and clinical programs for meeting the health care needs of society. -

Recommendation

BRITISH ASSOCIATION OF SOCIAL WORKERS NOMINATION OF MARGARET HUMPHREYS FOR THE IFSW ANDREW MOURAVIEFF-APOSTOL MEDAL RECOMMENDATION BASW is pleased to nominate Margaret Humphreys, Director of the Child Migrant Trust, for the IFSW Andrew Mouravieff-Apostol Medal. This nomination is supported by the Australian and Canadian associations. 'For decades, child migrants were lost and forgotten by our countries - both old and new. We didn't belong anywhere, we had no words to explain what had happened to us, or who we were. We were truly lost in the wilderness. Margaret found our families and brought us home, one by one. She stayed beside us and gave us a voice to help governments listen, and finally to understand. National Apologies in the UK and Australia are testament to her work, and to our refusal to give in or be silenced.' John Hennessey OAM (former child migrant, 2015) MARGARET HUMPHREYS Margaret Humphreys CBE, AO is a UK social worker who founded a multi-national social work agency. I worked with her in Nottingham (UK) soon after we both qualified in the 1970s. Always looking out for creative solutions, she set up an innovative post-adoption service 'Triangle,' in her own time. Margaret launched the Child Migrants Trust after a single referral for assistance, came into the local authority office in Nottingham, UK where she was working as a social worker. This led her to investigate and then to provide active support to people who had been ‘migrated’ from the UK to other countries as children in care over a long period, not ending until the 1960s. -

Ed Rutherford Director of Photography

Ed Rutherford Director of Photography Agents Silvia Llaguno Associate Agent Shannon Black [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0889 Andrew Naylor Assistant [email protected] Lizzie Quinn +44 (0) 203 214 0899 [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0911 Credits Television Production Company Notes THE SERPENT QUEEN Lionsgate Television / 3 Arts Dir: Stacie Passon 2021 Entertainment / Starz Exec Prods: Erwin Stoff, Francis Lawrence, Justin Haythe US Drama Republic / BBC Dir: Lisa Siwe 2020 Prod: Hannah Pescod LITTLE BIRDS Warp Films / Sky Atlantic Dir: Stacie Passon 2020 Exec Prods: Ruth McCance, Peter Carlton * Nominated: Best Photography - Drama & Comedy, RTS Craft & Design Awards 2020 * Nominated: Best Photography & Lighting: Fiction, BAFTA Craft Awards 2021 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes ENDEAVOUR Mammoth Screen / ITV Dir: Leanne Welham SERIES 6, EPISODE 3 - Prod: Deanne Cunningham "Confection" 2019 CHEAT Two Brothers Pictures / ITV Dir: Louise Hooper 2018 Prod: Lydia Hampson VANITY FAIR Amazon Studios / Mammoth Dir: James Strong 2018 Screen / ITV Prod: Julia Stannard VICTORIA Mammoth Screen / ITV / Dir: Jim Loach SERIES 2, EPS 5 & 6 Masterpiece Theatre Prod: Paul Frift 2017 QUACKS Lucky Giant / BBC Dir: Andy De Emmony 2017 Prod: Imogen Cooper ENDEAVOUR Mammoth Screen / ITV Dir: Jim Loach SERIES 4, EPISODE 4 - Prod: Helen Ziegler "Harvest" 2017 THE LAST HOTEL Sky Arts Dir: Enda Walsh 2016 Prod: