Bonanza Flat Conservation Area Resource Inventory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Instructions on How to Hold an OEC Bottle and Can Drive

Hold Your Own Bottle and Can Drive to Support OEC Thank you for being a Bottle Bonanza drive sponsor! Many of your friends and neighbors separate their NYS redeemable water/soda/beer cans and bottles and return them periodically to a store or redemption center for cash. Some can’t be bothered and simply discard them. Collecting these items and redeeming them makes them donors and you a fundraiser for Onondaga Earth Corps. Here are some steps to take to hold a successful bottle and can drive: 1. Decide when and where you want to hold your drive. Some people hold them in their neighborhood at their own house and ask their neighbors and friends to drop off their donations. Others choose to pick up the donations at the source. Decide what’s right for you! 2. Contact Pieter Keese to schedule your drive and arrange any support you might need. [email protected] 315-289-6776 (phone or text) When texting state your name and Bottle Bonanza intention. 3. Hand out flyers a week or two before the drive. Download the fillable PDF flyer at the Bottle Bonanza website and complete it with your drive information for distribution in your neighborhood. Use your social media savvy to alert your friends. 4. Hold your drive 5. Take your collection to the redemption center (list provided below). 6. Advise the redemption center that the proceeds are for Onondaga Earth Corps. Let them know if you have to make more than one trip and they will credit the account until you have completed your delivery. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

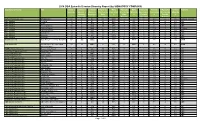

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

L O U I S I a N A

L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS L O U I S I A N A SPARROWS Written by Bill Fontenot and Richard DeMay Photography by Greg Lavaty and Richard DeMay Designed and Illustrated by Diane K. Baker What is a Sparrow? Generally, sparrows are characterized as New World sparrows belong to the bird small, gray or brown-streaked, conical-billed family Emberizidae. Here in North America, birds that live on or near the ground. The sparrows are divided into 13 genera, which also cryptic blend of gray, white, black, and brown includes the towhees (genus Pipilo), longspurs hues which comprise a typical sparrow’s color (genus Calcarius), juncos (genus Junco), and pattern is the result of tens of thousands of Lark Bunting (genus Calamospiza) – all of sparrow generations living in grassland and which are technically sparrows. Emberizidae is brushland habitats. The triangular or cone- a large family, containing well over 300 species shaped bills inherent to most all sparrow species are perfectly adapted for a life of granivory – of crushing and husking seeds. “Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Sparrows possess well-developed claws on their toes, the evolutionary result of so much time spent on the ground, scratching for seeds only seven species breed here...” through leaf litter and other duff. Additionally, worldwide, 50 of which occur in the United most species incorporate a substantial amount States on a regular basis, and 33 of which have of insect, spider, snail, and other invertebrate been recorded for Louisiana. food items into their diets, especially during Of Louisiana’s 33 recorded sparrows, Opposite page: Bachman Sparrow the spring and summer months. -

Bonanza' Ranch Rides Into Pop Culture Sunset

Powered by SAVE THIS | EMAIL THIS | Close 'Bonanza' ranch rides into pop culture sunset INCLINE VILLAGE, Nevada (Reuters) -- A great symbol of the rugged old West, or at least as it was portrayed by Hollywood, is riding off into the sunset. The Ponderosa Ranch, an American West theme park where the television show "Bonanza" was filmed, closed Sunday after its sale to a financier whose plans for the property are unclear. The show, which ran on NBC from 1959 to 1973, was the top-rated U.S. program in the mid-1960s. Before the park closed, it was easy with a little imagination to feel transported there to a time when the American West was still a place to be tamed. Wranglers and a Stetson were proper attire. A sign outside the Silver Dollar Saloon welcomed ladies and not just the ones who earn a living upstairs. Fans of the long-running "Bonanza," which still airs on cable television, may recall Little Joe and Hoss getting the horses ready while Ben Cartwright yells from his office to see if the boys were doing what they were told in the 1860s West. "The house is the part I recognize -- the fireplace, the dining room, his office, the kitchen," said Oliver Barmann, 38, from Hessen, Germany, who visited the 570-acre grounds a week before the Ponderosa Ranch closed. "It's a pity it is closing," he said as his wife, Silvia, nodded in agreement. The property with postcard views of Lake Tahoe along Nevada's border with California became a theme park in the late 1960s, after the color-filmed scenes of "Bonanza"-- a first for a Western TV show in its day -- became part of American television lore. -

BONANZA G36 Specification and Description

BONANZA G36 Specifi cation and Description E-4063 THRU E-4080 Contents THIS DOCUMENT IS PUBLISHED FOR THE PURPOSE 1. GENERAL DESCRIPTION ....................................2 OF PROVIDING GENERAL INFORMATION FOR THE 2. GENERAL ARRANGEMENT .................................3 EVALUATION OF THE DESIGN, PERFORMANCE AND EQUIPMENT OF THE BONANZA G36. IT IS NOT A 3. DESIGN WEIGHTS AND CAPACITIES ................4 CONTRACTUAL AGREEMENT UNLESS APPENDED 4. PERFORMANCE ..................................................4 TO AN AIRCRAFT PURCHASE AGREEMENT. 5. STRUCTURAL DESIGN CRITERIA ......................4 6. FUSELAGE ...........................................................4 7. WING .....................................................................5 8. EMPENNAGE .......................................................5 9. LANDING GEAR ...................................................5 10. POWERPLANT .....................................................5 11. PROPELLER .........................................................6 12. SYSTEMS .............................................................6 13. FLIGHT COMPARTMENT AND AVIONICS ...........7 14. INTERIOR ...........................................................12 15. EXTERIOR ..........................................................12 16. ADDITIONAL EQUIPMENT .................................12 17. EMERGENCY EQUIPMENT ...............................12 18. DOCUMENTATION & TECH PUBLICATIONS ....13 19. MAINTENANCE TRACKING PROGRAM ...........13 20. NEW AIRCRAFT LIMITED WARRANTY .............13 -

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER

Jae Blaze CREATIVE DIRECTOR/CHOREOGRAPHER ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ AWARDS/NOMINATIONS MTV Hip Hop Video - Black Eyed Peas “My Humps” MTV Best New Artist in a Vide - Sean Paul “Get Busy” (Nominee) TELEVISION/FILM King Of The Dancehall (Creative Director) Dir. Nick Cannon American Girl: Saige Paints The Sky Dir. Vince Marcello/Martin Chase Prod. American Girl: Alberta Dir. Vince Marcello Sparkle (Co-Chor.) Dir. Salim Akil En Vogue: An En Vogue Christmas Dir. Brian K. Roberts/Lifetime Tonight SHow w Gwen Stefani (Co-Chor.) NBC The X Factor (Associate Chor.) FOX Cheetah Girls 3: One World (Co-Chor.) Dir. Paul Hoen/Disney Channel Make It Happen (Co-Chor.) Dir. Darren Grant New York Minute Dir. D. Gorgon American Music Awards w/ Fergie (Artistic Director) ABC/Dick Clark Productions Divas Celebrate Soul (Co-Chor.) VH1 So You Think You Can Dance Canada Season 1-4 CTV Teen Choice Awards w/ Will.I.Am FOX American Idol w/ Jordin Sparks FOX American Idol w/ Will.I.Am FOX Superbowl XLV Halftime Show w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX/NFL Soul Train Awards BET Idol Gives Back w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) FOX Grammy Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) CBS / AEG Ehrlich Ventures NFL Thanksgiving Motown Tribute (Co-Chor.) CBS/NFL American Music Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Dick Clark Productions BET Hip Hop Awards (Co-Chor.) BET NFL Kickoff Concert w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) NFL Oprah w/ Black Eyed Peas (Co-Chor.) ABC/Harpo Teen Choice Awards w/ Black Eyed Peas -

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (By SIGNATORY COMPANY)

2014 DGA Episodic Director Diversity Report (by SIGNATORY COMPANY) Signatory Company Title Total # of Combined # Combined # Episodes Male # Episodes Male # Episodes Female # Episodes Female Network Episodes Women + Women + Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Directed by Caucasian Directed by Minority Minority Minority % Male % Male % Female % Female % Episodes Caucasian Minority Caucasian Minority 50/50 Productions, LLC Workaholics 13 0 0% 13 100% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% Comedy Central ABC Studios Betrayal 12 1 8% 11 92% 0 0% 1 8% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Castle 23 3 13% 20 87% 1 4% 2 9% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Criminal Minds 24 8 33% 16 67% 5 21% 2 8% 1 4% CBS ABC Studios Devious Maids 13 7 54% 6 46% 2 15% 4 31% 1 8% Lifetime ABC Studios Grey's Anatomy 24 7 29% 17 71% 1 4% 2 8% 4 17% ABC ABC Studios Intelligence 12 4 33% 8 67% 4 33% 0 0% 0 0% CBS ABC Studios Mixology 12 0 0% 13 108% 0 0% 0 0% 0 0% ABC ABC Studios Revenge 22 6 27% 16 73% 0 0% 6 27% 0 0% ABC And Action LLC Tyler Perry's Love Thy Neighbor 52 52 100% 0 0% 52 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN And Action LLC Tyler Perry's The Haves and 36 36 100% 0 0% 36 100% 0 0% 0 0% OWN The Have Nots BATB II Productions Inc. Beauty & the Beast 16 1 6% 15 94% 0 0% 1 6% 0 0% CW Black Box Productions, LLC Black Box, The 13 4 31% 9 69% 0 0% 4 31% 0 0% ABC Bling Productions Inc. -

Plum Tree Island National Wildlife Refuge Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment January 2017 Front Cover: Salt Marsh Jeff Brewer/USACE

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Plum Tree Island National Wildlife Refuge Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan and Environmental Assessment January 2017 Front cover: Salt marsh Jeff Brewer/USACE This blue goose, designed by J.N. “Ding” Darling, has become the symbol of the National Wildlife Refuge System. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is the principal Federal agency responsible for conserving, protecting, and enhancing fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. The Service manages the National Wildlife Refuge System comprised of over 150 million acres including over 560 national wildlife refuges and thousands of waterfowl production areas. The Service also operates 70 national fish hatcheries and over 80 ecological services field stations. The agency enforces Federal wildlife laws, manages migratory bird populations, restores nationally significant fisheries, conserves and restores wildlife habitat such as wetlands, administers the Endangered Species Act, and helps foreign governments with their conservation efforts. It also oversees the Federal Assistance Program which distributes hundreds of millions of dollars in excise taxes on fishing and hunting equipment to state wildlife agencies. Comprehensive Conservation Plans (CCPs) provide long-term guidance for management decisions on a refuge and set forth goals, objectives, and strategies needed to accomplish refuge purposes. CCPs also identify the Service’s best estimate of future needs. These plans detail program levels that are sometimes substantially above current budget allocations and, as such, are primarily for Service strategic planning and program prioritization purposes. CCPs do not constitute a commitment for staffing increases, operational and maintenance increases, or funding for future land acquisition. -

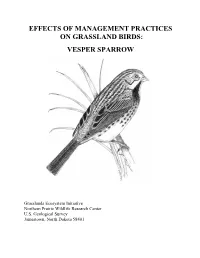

Vesper Sparrow

EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: VESPER SPARROW Grasslands Ecosystem Initiative Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center U.S. Geological Survey Jamestown, North Dakota 58401 This report is one in a series of literature syntheses on North American grassland birds. The need for these reports was identified by the Prairie Pothole Joint Venture (PPJV), a part of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan. The PPJV recently adopted a new goal, to stabilize or increase populations of declining grassland- and wetland-associated wildlife species in the Prairie Pothole Region. To further that objective, it is essential to understand the habitat needs of birds other than waterfowl, and how management practices affect their habitats. The focus of these reports is on management of breeding habitat, particularly in the northern Great Plains. Suggested citation: Dechant, J. A., M. F. Dinkins, D. H. Johnson, L. D. Igl, C. M. Goldade, and B. R. Euliss. 2000 (revised 2002). Effects of management practices on grassland birds: Vesper Sparrow. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Jamestown, ND. 41 pages. Species for which syntheses are available or are in preparation: American Bittern Grasshopper Sparrow Mountain Plover Baird’s Sparrow Marbled Godwit Henslow’s Sparrow Long-billed Curlew Le Conte’s Sparrow Willet Nelson’s Sharp-tailed Sparrow Wilson’s Phalarope Vesper Sparrow Upland Sandpiper Savannah Sparrow Greater Prairie-Chicken Lark Sparrow Lesser Prairie-Chicken Field Sparrow Northern Harrier Clay-colored Sparrow Swainson’s Hawk Chestnut-collared Longspur Ferruginous Hawk McCown’s Longspur Short-eared Owl Dickcissel Burrowing Owl Lark Bunting Horned Lark Bobolink Sedge Wren Eastern Meadowlark Loggerhead Shrike Western Meadowlark Sprague’s Pipit Brown-headed Cowbird EFFECTS OF MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ON GRASSLAND BIRDS: VESPER SPARROW Jill A. -

Illinois Birds: Volume 4 – Sparrows, Weaver Finches and Longspurs © 2013, Edges, Fence Rows, Thickets and Grain Fields

ILLINOIS BIRDS : Volume 4 SPARROWS, WEAVER FINCHES and LONGSPURS male Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder female Photo © John Cassady Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mary Kay Rubey Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder American tree sparrow chipping sparrow field sparrow vesper sparrow eastern towhee Pipilo erythrophthalmus Spizella arborea Spizella passerina Spizella pusilla Pooecetes gramineus Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder lark sparrow savannah sparrow grasshopper sparrow Henslow’s sparrow fox sparrow song sparrow Chondestes grammacus Passerculus sandwichensis Ammodramus savannarum Ammodramus henslowii Passerella iliaca Melospiza melodia Photo © Brian Tang Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Lincoln’s sparrow swamp sparrow white-throated sparrow white-crowned sparrow dark-eyed junco Le Conte’s sparrow Melospiza lincolnii Melospiza georgiana Zonotrichia albicollis Zonotrichia leucophrys Junco hyemalis Ammodramus leconteii Photo © Brian Tang winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Photo © Mark Bowman winter Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder summer Photo © Rob Curtis, The Early Birder Nelson’s sparrow -

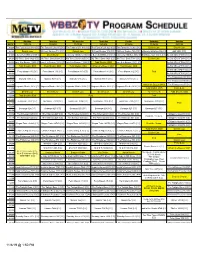

Me-TV Net Listings for 11-11-19 REV3

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday METV 11/11/19 11/12/19 11/13/19 11/14/19 11/15/19 11/16/19 11/17/19 06:00A The Facts of Life 918 {CC} The Facts of Life 915 {CC} The Facts of Life 914 {CC} The Facts of Life 920 {CC} The Facts of Life 921 {CC} Dietrich Law Dietrich Law 06:30A Dietrich Law Diff'rent Strokes 718 {CC} Dietrich Law Diff'rent Strokes 719 {CC} Diff'rent Strokes 720 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0064 {CC} ALF 2008 {CC} 07:00AThe Beverly Hillbillies 0059 {CC} Dietrich Law The Beverly Hillbillies 0060 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0061 {CC}The Beverly Hillbillies 0062 {CC}Bat Masterson 1021ASaved {CC} by the Bell (E/I) AFQ05 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 07:30A My Three Sons 6923 {CC} My Three Sons 6924 {CC} My Three Sons 6925 {CC} My Three Sons 6926 {CC} My Three Sons 7001 {CC} Dietrich LawSaved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ04 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:00ALeave It to Beaver 13205 {CC}Leave It to Beaver 13218 {CC}Leave It to Beaver 13220 {CC} Todd Shatkin, DDS Leave It to Beaver 13211 {CC} Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ06 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 08:30A Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS Todd Shatkin, DDS What's the Buzz in WNY Todd Shatkin, DDS Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFR10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 09:00A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ14 {CC} <E/I-13-16> Perry Mason 136 {CC} Perry Mason 139 {CC} Perry Mason 140 {CC} Perry Mason 141 {CC} Perry Mason 142 {CC} Paid 09:30A Saved by the Bell (E/I) AFQ10 {CC} <E/I-13-16> 10:00A The Flintstones 095 {CC} Matlock 9308 {CC} Matlock 9309 {CC} Matlock 9215 {CC} Matlock 93101 {CC} Matlock 93112 {CC} 10:30A The Flintstones