The Global State of Sustainable Insurance Understanding and Integrating Environmental, Social and Governance Factors in Insurance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DFA INVESTMENT DIMENSIONS GROUP INC Form NPORT-P Filed 2021-03-25

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM NPORT-P Filing Date: 2021-03-25 | Period of Report: 2021-01-31 SEC Accession No. 0001752724-21-062357 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DFA INVESTMENT DIMENSIONS GROUP INC Mailing Address Business Address 6300 BEE CAVE ROAD 6300 BEE CAVE ROAD CIK:355437| IRS No.: 363129984 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1031 BUILDING ONE BUILDING ONE Type: NPORT-P | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-03258 | Film No.: 21771544 AUSTIN TX 78746 AUSTIN TX 78746 (512) 306-7400 Copyright © 2021 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document DFA INVESTMENT DIMENSIONS GROUP INC. FORM N-Q REPORT January 31, 2021 (UNAUDITED) Table of Contents DEFINITIONS OF ABBREVIATIONS AND FOOTNOTES T.A. U.S. Core Equity 2 Portfolio Tax-Managed DFA International Value Portfolio T.A. World ex U.S. Core Equity Portfolio VA U.S. Targeted Value Portfolio VA U.S. Large Value Portfolio VA International Value Portfolio VA International Small Portfolio VA Short-Term Fixed Portfolio VA Global Bond Portfolio VIT Inflation-Protected Securities Portfolio VA Global Moderate Allocation Portfolio U.S. Large Cap Growth Portfolio U.S. Small Cap Growth Portfolio International Large Cap Growth Portfolio International Small Cap Growth Portfolio DFA Social Fixed Income Portfolio DFA Diversified Fixed Income Portfolio U.S. High Relative Profitability Portfolio International High Relative Profitability Portfolio VA Equity Allocation Portfolio DFA MN Municipal Bond Portfolio DFA California Municipal Real Return Portfolio DFA Global Core Plus Fixed Income Portfolio Emerging Markets Sustainability Core 1 Portfolio Emerging Markets Targeted Value Portfolio DFA Global Sustainability Fixed Income Portfolio DFA Oregon Municipal Bond Portfolio NOTES TO FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Organization Security Valuation Financial Instruments Federal Tax Cost Recently Issued Accounting Standards Other Subsequent Event Evaluations Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTINUED THE DFA INVESTMENT TRUST COMPANY SCHEDULES OF INVESTMENTS The U.S. -

Scheme Document

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. PART II (EXPLANATORY STATEMENT) OF THIS DOCUMENT COMPRISES AN EXPLANATORY STATEMENT IN COMPLIANCE WITH SECTION 897 OF THE COMPANIES ACT 2006. This Document contains a proposal which, if implemented, will result in the cancellation of the listing of RSA Shares on the Official List and of trading of RSA Shares on the London Stock Exchange. If you are in any doubt as to the contents of this Document or the action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000, if you are in the United Kingdom, or from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser if you are taking advice in a territory outside the United Kingdom. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred all of your RSA Shares or RSA ADSs, please send this Document together with the accompanying documents (other than documents or forms personal to you) at once to the purchaser or transferee, or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected, for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. However, such documents should not be forwarded or transmitted in or into or from any jurisdiction in which such act would constitute a violation of the relevant laws of such jurisdiction. If you sell or have sold or otherwise transferred only part of your holding of RSA Shares or RSA ADSs, you should retain these documents and contact the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected. -

Canada Rothschild/Soros Clan Lost Huge Investment in China's Ouster of Bo Xilai More Below Bilderber Timeline, Rothsch / China

NewsFollowUp.com Obama / CIA Franklin Scandal Omaha pictorial Index sitemap home Canada North American Union? ... Secret agenda is to dissolve the United States of America into the North Your browser does not support inline frames or American Union. ... is currently configured not to display inline controlled by frames. corporations ... no accountability. go to Immigration page WMR: Bilderberg Rothschild/Soros clan lost huge Timeline, Rothschild Canada investment in / China Your browser does not China's ouster of support inline frames or is currently configured not to Bo Xilai more display inline frames. below America for sale, How does this tie into NAU? North American Union Politics Resources related topics related topics related topics Environment Economics De-regulation Indigenous Rights Immigration Pharmaceuticals Labor Latin America Taxes War Global Collectivism PROGRESSIVE REFERENCE CONSERVATIVE* Americas American Society of International Law, see also Accenture formerly Andersen Consulting, see Amnesty International ECOSOC on North American Union. Enron, Kenneth Lay, Jeffrey Skilling, Bush from Canadians.org Deep Integration of U.S. and Center for North American Studies, American Accuracy in Media portrays NAU as a left-wing Canadian economies regulation, standards University, Professor Robert Pastor, said to be conspiracy ..."AIM has previously documented governing health, food safety, father of NAU, and his book "Towards a North that Pastor's campaign for a North American wages. Harmonization process a demand -

Distribution Strategies in Insurance Understanding the Customer View DISTRIBUTION STRATEGIES in INSURANCE

Distribution Strategies in Insurance Understanding the Customer View DISTRIBUTION STRATEGIES IN INSURANCE Executive Insurers are, by their very nature, cautious. As a result, they will often focus more on the risks of summary new developments as much as the potential opportunities. The evolution of the insurance as likely to use instant messaging or sales process however, and the web chats as they are face-to-face widespread adoption of digital meetings (5%) when communicating channels in every walk of life, has with their insurer. made insurers sit up and take note. Most now realise that they must The survey cautions against making interact with their customers – at simplistic assumptions, however. least to some extent – whenever, Respondents most comfortable with however and through whichever technology were not the youngest channel their customer desires. We group, as you might expect, but have commissioned this research those aged 35-44. In fact, surprisingly, to better understand consumers’ the youngest respondents were most expectations and gauge how well likely to interact face-to-face than any insurers currently measure up. other age group. The survey, based on the responses A key aspect of the findings is clear: of more than 2,000 working age insurers need both compelling adults in the UK, highlights that traditional and digital channels. It consumers are becoming more savvy is on the latter, however, that they when purchasing their insurance. seem most at risk of falling short. The For example, consumers are almost research found that more than one in as likely to prioritise the ease of three consumers find buying or obtaining a quote (36%) as much as renewing a policy online “very the brand of the insurer (42%). -

2019 Insurance Fact Book

2019 Insurance Fact Book TO THE READER Imagine a world without insurance. Some might say, “So what?” or “Yes to that!” when reading the sentence above. And that’s understandable, given that often the best experience one can have with insurance is not to receive the benefits of the product at all, after a disaster or other loss. And others—who already have some understanding or even appreciation for insurance—might say it provides protection against financial aspects of a premature death, injury, loss of property, loss of earning power, legal liability or other unexpected expenses. All that is true. We are the financial first responders. But there is so much more. Insurance drives economic growth. It provides stability against risks. It encourages resilience. Recent disasters have demonstrated the vital role the industry plays in recovery—and that without insurance, the impact on individuals, businesses and communities can be devastating. As insurers, we know that even with all that we protect now, the coverage gap is still too big. We want to close that gap. That desire is reflected in changes to this year’s Insurance Information Institute (I.I.I.)Insurance Fact Book. We have added new information on coastal storm surge risk and hail as well as reinsurance and the growing problem of marijuana and impaired driving. We have updated the section on litigiousness to include tort costs and compensation by state, and assignment of benefits litigation, a growing problem in Florida. As always, the book provides valuable information on: • World and U.S. catastrophes • Property/casualty and life/health insurance results and investments • Personal expenditures on auto and homeowners insurance • Major types of insurance losses, including vehicle accidents, homeowners claims, crime and workplace accidents • State auto insurance laws The I.I.I. -

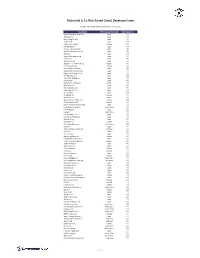

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Global Developed Index

Rothschild & Co Risk-Based Global Developed Index Indicative Index Weight Data as of January 31, 2020 on close Constituent Exchange Country Index Weight (%) Nippon Telegraph & Telephone C Japan 1.11 Softbank Corp Japan 1.10 Nitori Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.75 Toshiba Corp Japan 0.67 Kirkland Lake Gold Ltd Canada 0.61 NTT DOCOMO Inc Japan 0.58 Mizuho Financial Group Inc Japan 0.54 Takeda Pharmaceutical Co Ltd Japan 0.50 KDDI Corp Japan 0.49 Japan Post Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.48 Subaru Corp Japan 0.48 Sekisui House Ltd Japan 0.45 Singapore Telecommunications L Singapore 0.45 Franco-Nevada Corp Canada 0.43 Oriental Land Co Ltd/Japan Japan 0.43 Chugai Pharmaceutical Co Ltd Japan 0.40 Nippon Paint Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.39 Fast Retailing Co Ltd Japan 0.38 Tokio Marine Holdings Inc Japan 0.38 ITOCHU Corp Japan 0.38 Bandai Namco Holdings Inc Japan 0.37 Bridgestone Corp Japan 0.36 MEIJI Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.35 Japan Airlines Co Ltd Japan 0.34 Unicharm Corp Japan 0.33 Aroundtown SA Germany 0.33 Ajinomoto Co Inc Japan 0.33 Algonquin Power & Utilities Co Canada 0.32 Deutsche Wohnen SE Germany 0.32 MS&AD Insurance Group Holdings Japan 0.32 Lamb Weston Holdings Inc United States 0.32 ANA Holdings Inc Japan 0.32 Evergy Inc United States 0.32 Kirin Holdings Co Ltd Japan 0.32 Asahi Group Holdings Ltd Japan 0.32 Shiseido Co Ltd Japan 0.32 Wesfarmers Ltd Australia 0.32 Cboe Global Markets Inc United States 0.32 Canon Inc Japan 0.31 Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd Singapore 0.31 Kao Corp Japan 0.31 Secom Co Ltd Japan 0.31 Agnico Eagle Mines Ltd Canada 0.31 -

Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017

Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 Appendix D - Securities Held by Funds October 18, 2017 Annual Report of Activities Pursuant to Act 44 of 2010 October 18, 2017 Appendix D: Securities Held by Funds The Four Funds hold thousands of publicly and privately traded securities. Act 44 directs the Four Funds to publish “a list of all publicly traded securities held by the public fund.” For consistency in presenting the data, a list of all holdings of the Four Funds is obtained from Pennsylvania Treasury Department. The list includes privately held securities. Some privately held securities lacked certain data fields to facilitate removal from the list. To avoid incomplete removal of privately held securities or erroneous removal of publicly traded securities from the list, the Four Funds have chosen to report all publicly and privately traded securities. The list below presents the securities held by the Four Funds as of June 30, 2017. 1345 AVENUE OF THE A 1 A3 144A AAREAL BANK AG ABRY MEZZANINE PARTNERS LP 1721 N FRONT STREET HOLDINGS AARON'S INC ABRY PARTNERS V LP 1-800-FLOWERS.COM INC AASET 2017-1 TRUST 1A C 144A ABRY PARTNERS VI L P 198 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP ABRY PARTNERS VII L P 1MDB GLOBAL INVESTMENTS L ABAXIS INC ABRY PARTNERS VIII LP REGS ABB CONCISE 6/16 TL ABRY SENIOR EQUITY II LP 1ST SOURCE CORP ABB LTD ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS II LP 200 INVERNESS DRIVE WEST ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS IV LP 21ST CENTURY FOX AMERICA INC ABBOTT LABORATORIES ABS CAPITAL PARTNERS V LP 21ST CENTURY ONCOLOGY 4/15 -

Phoenix Group Holdings Annual Report and Accounts 2013 2013 Was an Eventful Year for the Phoenix Group

PHOENIX GROUP HOLDINGS ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2013 2013 WAS AN EVENTFUL YEAR FOR THE PHOENIX GROUP. WE HAVE PROGRESSED IN STRENGTHENING THE BALANCE SHEET AND SIMPLIFYING THE GROUP’S STRUCTURE AND WE HAVE ALSO DELIVERED AGAINST OUR FINANCIAL TARGETS. BUSINESS OVERVIEW OUR BUSINESS MODEL delivering strong investment Phoenix Group is the UK’s largest specialist As a closed life fund consolidator, Phoenix performance and high quality closed life and pension fund consolidator Life focuses on the efficient run-off of service to its clients. with over 5 million policyholders and existing policies, maximising economies £68.6 billion of Group assets under of scale and generating capital efficiencies For a detailed look at management. Our business manages through operational improvements. our business model closed life funds in an efficient and Ignis Asset Management focuses on Turn to page 12 secure manner, protecting and enhancing policyholders’ interests whilst maximising value for the Group’s shareholders. PHOENIX LIFE Aims to deliver innovative financial management and operational excellence PHOENIX GROUP Delivery of IGNIS ASSET MANAGEMENT strategic initiatives Aims to deliver superior investment performance and client service EVOLUTION OF THE PHOENIX GROUP The following shows the Group’s original entities and their various acquisitions over the years. 1806 1857 2008 2009 2010 London Life Pearl Loan Company Pearl Group Liberty Pearl Group renamed established established acquires Acquisition Phoenix Group Resolution plc Holdings Holdings and -

Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux)

Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Unaudited Semi-Annual Report at 30.09.2008 Investment fund under Luxembourg law Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) • Unaudited Semi-Annual Report at 30.09.2008 Table of Contents Page 2 Management and Administration 3 Consolidated Report 5 Report by Subfund Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Asian Property 9 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Asian Tigers 13 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Brazil 18 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Convergence Europe 22 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Dividend Europe 26 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Eastern Europe 30 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Emerging Markets 34 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) European AlphaMax 40 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) European Blue Chips 41 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) European Property 46 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Future Energy 50 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Germany 55 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Biotech 56 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Communications 60 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Financials 64 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global InfoTech 65 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Prestige 70 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Resources 74 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Global Security 78 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Greater China 82 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Infrastructure 86 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Italy 91 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Japan Megatrend 95 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Latin America 99 Credit Suisse Equity Fund (Lux) Leading Brands 104 Credit Suisse Equity -

Atlantic Insurance Brokers Winter 2016

Atlantic Insurance Brokers ~1~ Winter 2016 WINNIPEG, MB CHAMPION, AB WHITBY, ON LANGLEY, BC HALIFAX, NS VANCOUVER, BC We are very excited to call Halifax, NS our home, and heading up our newest oce is BLAIR COADY! He comes to SRIM with over 10 years of experience within the industry on the Property and Casualty side. His knowledge and regional expertise of Atlantic Canada makes him a true asset and we are proud he’s calling SRIM his home! Try Blair and SRIM out on the following risks: • Hard to Place Liability • Resorts • Vacant Risks • Property • Contractors • Professional Liability Blair Coady Atlantic Manager of Business • Sports & Entertainment • Logging • Aviation & Drones Development & Underwriting • Golf Courses • Motor Truck Cargo • Marinas & Commercial Marine [email protected] [email protected] 902.402.1376 CONTACT SRIM FOR MORE INFORMATION: [email protected] www.srim.ca Thank you to all our brokers for voting SRIM an ALL-STAR MGA in Insurance Business Magazine’s “Rate Your MGAs” 2016 edition! We truly appreciate the support! Special Risk Insurance Managers Ltd. is proud to be your Mark Woodall Tom Willie independently owned and operated Canadian MGA, working President & CEO Director & Chief Underwriting Ocer Atlanticwith you on theInsurance ever-changing Brokers needs of your clients. [email protected] [email protected] Winter 2016 Whether your client’s construction company is large, small or something in between, we cover it. Small construction companies are different from mid-size companies. And they’re both different from the big guys. That’s why, at Travelers Canada, we have dedicated account executives, risk control and claims specialists with an in-depth knowledge of construction companies of every size. -

Report of the Independent Expert on the Proposed Transfer of Certain Legacy Business from Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance

Milliman Report Report of the Independent Expert on the proposed transfer of certain legacy business from Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance PLC and from The Marine Insurance Company Limited to Mercantile Indemnity Company Limited Prepared by: Derek Newton FIA Milliman LLP 11 Old Jewry London, EC2R 8DU United Kingdom Tel +44 (0)20 7847 1500 Fax +44 (0)20 7847 1501 uk.milliman.com 16 January 2019 Milliman Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE 3 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 10 3. BACKGROUND REGARDING THE REGULATORY ENVIRONMENTS 14 4. BACKGROUND REGARDING THE ENTITIES CONCERNED IN THE SCHEME 22 5. THE PROPOSED SCHEME 45 6. THE IMPACT OF THE SCHEME ON THE TRANSFERRING POLICYHOLDERS 58 7. THE IMPACT OF THE SCHEME ON THE POLICYHOLDERS OF THE TRANSFERORS WHO WILL NOT TRANSFER UNDER THE SCHEME 88 8. OTHER CONSIDERATIONS 90 9. CONCLUSIONS 96 APPENDIX A DEFINITIONS 97 APPENDIX B CORPORATE STRUCTURE OF THE RSA GROUP 104 APPENDIX C CORPORATE STRUCTURE OF THOSE PARTS OF THE ENSTAR GROUP THAT ARE RELEVANT TO THE SCHEME 105 APPENDIX D CV FOR DEREK NEWTON 106 APPENDIX E SCOPE OF THE WORK OF THE INDEPENDENT EXPERT IN RELATION TO THE SCHEME 108 APPENDIX F GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS OF THE INDEPENDENT EXPERT 109 APPENDIX G KEY SOURCES OF DATA 111 APPENDIX H SOLVENCY II BALANCE SHEET 114 2 Report of the Independent Expert on the proposed transfer of certain legacy business from Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance PLC and from The Marine Insurance Company Limited to Mercantile Indemnity Company Limited 16 January 2019 Milliman Report 1. PURPOSE AND SCOPE PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT 1.1 It is proposed that particular blocks of business of Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance plc (“RSAI”) and of The Marine Insurance Company Limited (“MIC”) be transferred to Mercantile Indemnity Company Limited (“Mercantile”) by an insurance business transfer scheme (“the Scheme”), as defined in Section 105 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”). -

Global Institutional Investors

Sponsor/entity Country 2016 (€’000s) 2015 (€’000s) 55 Shichousonren Japan 77,044,867 75,120,315 56 Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp. US 76,148,787 65,698,416 57 AMP Superannuation Ltd. Australia 76,006,236 67,437,170 58 AT&T Inc. US 74,682,213 70,417,935 59 Ford Motor Company US 74,057,227 69,926,130 Top 1000 60 Georgia Division of Investment Services US 73,647,088 58,954,951 61 General Motors Corporation US 72,929,963 68,666,219 62 Minnesota State Board of Investment US 72,247,570 75,242,253 63 Michigan Department of Treasury US 71,347,168 73,329,840 64 Ohio State Teachers Retirement System US 70,196,775 55,925,483 65 California State Treas. Off., Invest. Division US 69,395,919 47,366,853 66 General Electric Company US 69,259,275 60,112,239 Global 67 AustralianSuper Australia 68,763,875 54,778,326 68 Universities Superannuation Scheme Ltd. UK 68,457,491 52,175,864 69 Pensioenfonds Metaal en Techniek (PMT) Netherlands 67,999,195 62,700,000 70 British Columbia Pension Corporation Canada 67,705,693 65,533,949 71 Lloyds Banking Group UK 67,486,923 50,442,697 72 Kaiser Permanente US 67,438,033 50,795,413 Institutional 73 Russian Federation National Wealth Fund Russia 67,420,652 64,931,218 74 Organization for SME and Regional Innov. Japan 66,725,407 67,457,340 75 Kazakhstan National Fund Kazakhstan 66,678,834 74,989,200 76 Ontario Municipal Emp.