BBN Wetland Plan Draft 29-05-06

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Groundwater Management Plan for the Katunga Water Supply Protection Area 2006

Groundwater Management Plan for the Katunga Water Supply Protection Area 2006 KATUNGA WATER SUPPLY PROTECTION AREA GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN – 2006 I, John Thwaites, Minister for Water, approve this management plan in accordance with section 32A(6) of the Water Act 1989. JOHN THWAITES Minister for Water Date: 24/7/06 Document Number: 4250418 i KATUNGA WATER SUPPLY PROTECTION AREA GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN – 2006 Quick Reference Guide to the Plan Rules PRESCRIPTION 1: Limit on entitlement (Page 12) GMW must not approve an application for a groundwater licence if the approval of the application would cause: a) The Permissible Consumptive Volume to be exceeded; b) The total groundwater entitlement within a 2 km radius of the proposed extraction site exceeding 3,700 ML/year; or c) The following zone limits to be exceeded. Management zone Zone limit (ML/year) North Western Dryland Zone (1061) 6,500 Numurkah-Nathalia Zone (1062) No limit Cobram Zone (1063) 25,000 Katunga WSPA Management Zones PRESCRIPTION 2: Restrictions on taking groundwater (Page 14) By 1 July each year GMW will: a) Determine the rolling average of the maximum annual groundwater recovery levels from the preceding five irrigation seasons for bores listed in Schedule 1 (page 24) and announce a corresponding allocation for the subsequent irrigation season as detailed below: Trigger level depth below natural Allocation surface (m) 21.0 and above 100% 21.1 to 24.0 70% 70% and review undertaken by GMW in consultation Below 24.1 with Katunga Groundwater Reference Group b) Announce allocations by listing them on its website, sending letters to all licence holders and placing public notices in local newspapers. -

Cause of Water Issues a Mystery

Phone 5862 1034 – Fax 5862 2668 – Email - Editorial: [email protected] - Advertising: [email protected] – Registered by Australia Post – Publication No. VA 1548 established 1895 LEADER NumurkahWEDNESDAY, JANUARY 29, 2020 $1.30 INSIDE Our top citizen See story page 3 Numurkah’s newest Aussies ...Teruko Smith, Srisoi Praphasiri, Runsip Morris, Amy Paisley, Glen Gamble, Edith Gamble and William Gamble were all excited to take the pledge of citizenship. See story page 6. New Aussies add Community generosity strength to Moira Shire See story page 5 Cause of water issues a mystery NUMURKAH and Wunghnu residents have ly, one reason for the delay in fresh smelling and in the next week - people will experience the ef- had two very simple questions about their water tasting water coming out of local taps is the recent fects of the treatment we’ve been doing here. the past couple of weeks - what is causing it to rain. As for question number one, despite extensive smell and taste funny, and when will it go back to “When people turn on the tap in Numurkah analysis of the water at the storage and treatment normal? or Wunghnu, the water comes from the stor- plant, there is no way to be completely sure about To answer the second question first, hopeful- age tanks and towers in those places, which is what caused the issue. ly, by the time you are reading this the taste and pumped from the storage facility for bulk use by GVW manager of water quality Mark Putman smell of our water should be back to normal. -

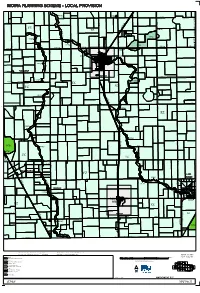

Moira Planning Scheme

STACEY RD PUZ6 RD WALDEN RD PUZ4 RD SCHOOL Creek MOIRAMOIRARD PLANNINGPLANNING SCHEMESCHEME -- LOCALLOCAL PROVISIONPROVISION RDZ1 RD RD RD FZ STACEY SCHOOL BURRAMINE PPRZ PUZ5 RAILWAY RD FISHER LA CEMETERY RD FISHER KENNEDY BENALLA - YARRAWONGA TUNGAMAH THREE CHAIN CARMODY RD ROAD ROAD FZ PUZ4 ROAD FZ FZ ROAD Boosey PPRZ ROAD PPRZ RDZ1 RD PPRZ Creek RD Broken PPRZ RD RD PPRZ RD RD ST. JAMES AND YARRAWONGA TUNGAMAH RDZ1 FZ FZ RD PUZ4 RDZ1 RDZ1 RDZ1 TUNGAMAH RD RDZ1 CHINAMANS LA RDZ1 RD TUNGAMAH - PEECHELBA RDZ1 TUNGAMAH HOLMES FZ RDZ1 PPRZ FZ RDZ1 RAINE BLAIR FZ LAWRENCE PUZ4 TUNGAMAH SCHOOL TUNGAMAH TZ TZ FZ TUNGAMAHTUNGAMAHTUNGAMAH RD TUNGAMAHTUNGAMAHTUNGAMAH ST PPRZ SPRYRDZ1 RDZ1 PPRZ BooseyPPRZ TZ Boosey PUZ4 TZ FOR THIS AREA Creek UFZ Creek PPRZ UFZ RD PPRZ Boosey PPRZ ROAD FZ SEERUZ MAP 34 PUZ1 ROAD TZ RD RD YOUARANGYOUARANG FZ SAUNDERS YOUARANGYOUARANG RD RD HENRY PUZ4 FZ CRENNAN ANGLE TUNGAMAHTUNGAMAH TUNGAMAHTUNGAMAH ROAD KREECK RD DEVENISH PPRZ PPRZ BUERCKNER RD FZ FZ ROAD FZ ROAD ROAD PPRZ ROAD PUZ4 ROAD RD RD RD RD RD RD RD RD PELLUEBLA PELLUEBLA PELLY ST. JAMES AND YARRAWONGA WREN HAMMOND YUNDOOL HILL GEARY DRYSDALE PPRZ MOODIE FZ RDZ1 RD Creek ROAD ALMONDS RD BENALLA - YARRAWONGA RD PPRZ ROAD RD RD PETTIT WRIGHT RD RD DEVENISH RD HOWDEN ROAD ROAD Creek PPRZ WILLIS PCRZ PUZ4 PCRZ PPRZ ROAD ROAD RAILWAY PCRZ FZ RD RD ROAD RD RD RD FZ RD WANGARATTA RD PPRZ COOPER RD McLAUGHLIN HOLMES PELLY BENALLA - TOCUMWAL KELLY Boosey RD ROAD YUNDOOL FZ ROAD ROAD ROAD WAGGARANDALLWAGGARANDALL ROAD FZ RD LAKELAKE RD SPRING LA PPRZ ROWANROWAN RD MACARTNEY RD CHESTER RD MAHONEY RD MURPHY BEGGS RDZ1 NELSON BOXWOOD COLES RDZ1 OLD Broken RD ROAD CHURCH HUSBAND HILL ST PUZ1 Creek BARR ST YUNDOOLYUNDOOL ROAD PUZ4 ST RD PPRZ ST RD WAGGARANDALL RD RD ST PPRZ ST.ST.ST. -

Taylors Hill-Werribee South Sunbury-Gisborne Hurstbridge-Lilydale Wandin East-Cockatoo Pakenham-Mornington South West

TAYLORS HILL-WERRIBEE SOUTH SUNBURY-GISBORNE HURSTBRIDGE-LILYDALE WANDIN EAST-COCKATOO PAKENHAM-MORNINGTON SOUTH WEST Metro/Country Postcode Suburb Metro 3200 Frankston North Metro 3201 Carrum Downs Metro 3202 Heatherton Metro 3204 Bentleigh, McKinnon, Ormond Metro 3205 South Melbourne Metro 3206 Albert Park, Middle Park Metro 3207 Port Melbourne Country 3211 LiQle River Country 3212 Avalon, Lara, Point Wilson Country 3214 Corio, Norlane, North Shore Country 3215 Bell Park, Bell Post Hill, Drumcondra, Hamlyn Heights, North Geelong, Rippleside Country 3216 Belmont, Freshwater Creek, Grovedale, Highton, Marhsall, Mt Dunede, Wandana Heights, Waurn Ponds Country 3217 Deakin University - Geelong Country 3218 Geelong West, Herne Hill, Manifold Heights Country 3219 Breakwater, East Geelong, Newcomb, St Albans Park, Thomson, Whington Country 3220 Geelong, Newtown, South Geelong Anakie, Barrabool, Batesford, Bellarine, Ceres, Fyansford, Geelong MC, Gnarwarry, Grey River, KenneQ River, Lovely Banks, Moolap, Moorabool, Murgheboluc, Seperaon Creek, Country 3221 Staughtonvale, Stone Haven, Sugarloaf, Wallington, Wongarra, Wye River Country 3222 Clilon Springs, Curlewis, Drysdale, Mannerim, Marcus Hill Country 3223 Indented Head, Port Arlington, St Leonards Country 3224 Leopold Country 3225 Point Lonsdale, Queenscliffe, Swan Bay, Swan Island Country 3226 Ocean Grove Country 3227 Barwon Heads, Breamlea, Connewarre Country 3228 Bellbrae, Bells Beach, jan Juc, Torquay Country 3230 Anglesea Country 3231 Airleys Inlet, Big Hill, Eastern View, Fairhaven, Moggs -

Fishing on Information Further For

• www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/fisheries/recreational at online View any time. any of fish that a person is allowed to have in their possession at at possession their in have to allowed is person a that fish of waters: NSW for rules fishing on information further For • Possession limits: Possession type particular a of number maximum The phones. smart and waters; identified the in taken • for app Guide Fishing Recreational Victorian the Download • Closed seasons: Closed be cannot species fish certain which in period the • or ; www.vic.gov.au/fisheries at online View • Bag limits: Bag day; one in take to permitted are you fish of number • ; 186 136 on Centre Service Customer Call it; keep to allowed be to you for and practices: and • Size limits: Size minimum or maximum size a fish must be in order order in be must fish a size maximum or minimum Recreational Fishing Guide for further information on fishing rules rules fishing on information further for Guide Fishing Recreational recreational fishing. Rules and regulations include: regulations and Rules fishing. recreational Obtain a free copy of the Inland Angling Guide and the Victorian Victorian the and Guide Angling Inland the of copy free a Obtain It is important to be aware of the rules and regulations applying to to applying regulations and rules the of aware be to important is It From most Kmart stores in NSW. in stores Kmart most From • Lake Mulwala Angling Club Angling Mulwala Lake • Fish By the Rules the By Fish agents, and agents, Nathalia Angling Club Angling Nathalia • From hundreds of standard and gold fishing fee fee fishing gold and standard of hundreds From • Numurkah Fishing Club Fishing Numurkah • By calling 1300 369 365 (Visa and Mastercard only), only), Mastercard and (Visa 365 369 1300 calling By • used to catch Spiny Freshwater Crayfish. -

Vic Making Healthy Farmers

Cobram Courier 27/02/2008 Page: 11 Page 1 of 2 General News Region: Cobram VIC Circulation: 3218 Type: Regional Size: 403.47 sq.cms --W---- Making healthy farmers Farmers from Strathmerton and sur- of United Dairyfarmers of Victoria. rounding areas attended a Sustainable SustainableFarm Familiesisan Farm Families workshop last week as award-winning initiative of Western Dis- part of a statewide initiative to helptrict Health Service, based in Hamilton, improve the health of local farmers andand is delivered in partnership with the their families. Department of Primary Industries (DPI) The Sustainable Farm Families pro- as part of their longer term drought work. gram aims to develop the knowledge of farmers regarding their own health, with Farmers who have completed the pro- a focus on what practical steps can begram saidit enhanced theiroverall taken to improve the livesof farmhealth with everything from better eating families and the impact this improve-to improved farm safety. ment can deliver to their businesses. Some also found they were able to Participant Phil Gundrill said he sawmake better decisions because they had a the benefit of the workshop. new perspective of how important their "The workshops were excellent and health and families were in their lives. over the two days I certainly learned a lot about my health," he said. All of the participants will return to "We all received a free health assess-complete another two-day workshop in ment and the workshop sessions were12 months time, again receiving a health interactive, and I think everyone enjoyedassessment so they can track their health themselves." indicators over time. -

Leader Will Still Go On

Phone 5862 1034 – Fax 5862 2668 – Email - Editorial: [email protected] - Advertising: [email protected] – Registered by Australia Post – Publication No. VA 1548 established 1895 LEADER NumurkahWEDNESDAY, MARCH 25, 2020 $1.30 INSIDE New Lions PJ Day See story page 7 LIONS new and old keeping their distance in unique induction... New Numurkah Lions members and their nominees, from left: Chris Boyden, Keith Nicoll, Sue McCracken, Jack Fischer, Harry Fischer, Mark Nordbye, district governor Omen Ndlovu, David Morris, Elsie Sparrowhawk and Lea Tyndall. See story page 4. Leader will COVID-19 case Tanya confi rmed closes in Moira still gochanged. on A CASE of COVID-19 has been con rmed in Moira Shire. AS this edition of the Leader hits news stands we are all facing extraor- We have already enacted a number Yarrawonga Health o cially con rmed yesterday that a person who salon dinary times. of measures designed to keep Lead- presented to its urgent care centre last week has tested positive to the In coming weeks many businesses in er sta and customers safe - includ- virus. See story page 3 Numurkah, and across the state, may ing stringent cleaning practices and e person was mandatory isolating a er returning from overseas, be forced to close their doors - indef- card-only payment - and from here on when they developed symptoms. initely. out, we will be conducting as much Telephone contact was made, followed by presentation to Yarrawon- e Leader, as a regional newspaper, business as possible via telephone and ga Health. Infection control procedures were implemented immediately is listed as an essential business and email to avoid face to face contact. -

Figure 10 Goulburn Valley Waste and Resource Recovery Region

145°0'0"E 146°0'0"E ( (( SHEPPARTON MOOROOPNA STRATHMERTON COBRAM LEITCHVILLE GUNBOWER ( S " 0 ' PICOLA KATUNGA 0 ° S YARRAWONGA 6 " BUNDALONG 3 0 ' 0 ° TORRUMBARRY BARMAH 6 WAAIA 3 NATHALIA KATAMATITE ( NUMURKAH EC(HUCA WUNGHNU ECHUCA TUNGAMAH WYUNA KATANDRA PEECHELBA WYUNA WEST MITIAMO STRATHALLAN TONGALA TONGALA LOCKINGTON STRATHALLAN UNDERA LOCKINGTON KYABRAM DOOKIE KYABRAM ( ( THOONA ROCHESTER SHEPPARTON ( ROCHESTER GIRGARRE ARDMONA GIRGARRE MOOROOPNA GOORAMBAT CENTRAL TATURA KIALLA OXLEY COROP STANHOPE DRUMMARTIN COROP STANHOPE ELMORE BENALLA RAYWOOD ARCADIA MOYHU COLBINABBIN RUSHWORTH BADDAGINNIE RUSHWORTH MURCHISON MIEPOLL WHROO VIOLET TOWN MOLYULLAH WHROO BARNADOWN HUNTLY TATONG TOOLLEEN EUROA SWANPOOL MARONG NAGAMBIE AXEDALE GRAYTOWN KANGAROO FLAT LOCKWOOD TABILK MITCHELLSTOWN AXE STRATHBOGIE CREEK SEDGWICK RAVENSWOOD AVENEL TOOMBULLUP S MERTON " 0 ' 0 PUCKAPUNYAL ° S 7 " 3 0 ' BONNIE 0 HARCOURT ° SEYMOUR DOON 7 REDESDALE TOOBORAC ( 3 ( MANSFIELD YARCK MERRIJIG TALLAROOK (MOUNT BULLER) PYALONG GLENAROUA KERRISDALE CATHKIN MOLESWORTH TARADALE GOUGHS ALEXANDRA BAY BROADFORD MACS MALMSBURY YEA ( EILDON COVE LIMESTONE KYNETON SNOBS CREEK LANCEFIELD CARLSRUHE JAMIESON KILMORE FLOWERDALE TAGGERTY RUBICON CLONBINANE WANDONG BYLANDS HEATHCOTE JUNCTION BUXTON MOUNT MACEDON WALLAN GLENBURN ENOCHS POINT BULLARTO MONEGEETTA SOUTH MACEDON Gouldburn Valley Waste and Resource NEW RIDDELLS GISBORNE CREEK KINGLAKE WEST BLACKWOODRecovery Group CLARKEFIELD BULLENGAROOK WHITTLESEA MARYSVILLE KINGLAKE TOOLANGI NARBETHONG MATLOCK ST ANDREWS TOOLERN -

'Secret and Deceitful' Brumby Shootings Outrage Sanctuary Builders

Phone 5862 1034 – Fax 5862 2668 – Email - Editorial: [email protected] - Advertising: [email protected] – Registered by Australia Post – Publication No. VA 1548 established 1895 LEADER NumurkahWEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021 $1.30 INSIDE Top of her gameNews See story page X3 FIGHTING ... Julie Pridmore is at her wits end after the A cuppa long-standing fi ght with Parks Victoria. See story below. withNews Lou See story pagepages X 7 & 8 ‘Secret and deceitful’ brumby shootings outrage sanctuary builders THE Barmah Brumby Preservation Group animal grazing is having an ongoing impact on the “To ensure the safety of sta and contractors and (BBPG) is claiming that Parks Victoria (PV) has park .” the welfare of horses, operational details of feral been shooting brumbies in the Barmah National e BBPG has accepted that PV will rid the forest horse management operations are not made public- Park, despite agreeing not to shoot any this year. of brumbies, and that some will be shot in order to ly available,” the spokesperson said. With donations coming from right across Victoria, do so. e frustrations of the members of the BBPG Julie explained the BBPG’s side of the story to the Australia, and indeed the world, the BBPG raised lie with PV allegedly going behind their backs and Leader about $90,000 to build a purpose-built ‘sanctuary’, shooting brumbies in recent weeks, despite agreeing “Parks Vic has a strategic plan, that it removes up to on the doorstep of the Barmah National Park, in not to shoot any this year. Julie Pridmore, an active member of the preserva- 100 brumbies by the end of June,” Julie said. -

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria

List of Parishes in the State of Victoria Showing the County, the Land District, and the Municipality in which each is situated. (extracted from Township and Parish Guide, Department of Crown Lands and Survey, 1955) Parish County Land District Municipality (Shire Unless Otherwise Stated) Acheron Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Addington Talbot Ballaarat Ballaarat Adjie Benambra Beechworth Upper Murray Adzar Villiers Hamilton Mount Rouse Aire Polwarth Geelong Otway Albacutya Karkarooc; Mallee Dimboola Weeah Alberton East Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alberton West Buln Buln Melbourne Alberton Alexandra Anglesey Alexandra Alexandra Allambee East Buln Buln Melbourne Korumburra, Narracan, Woorayl Amherst Talbot St. Arnaud Talbot, Tullaroop Amphitheatre Gladstone; Ararat Lexton Kara Kara; Ripon Anakie Grant Geelong Corio Angahook Polwarth Geelong Corio Angora Dargo Omeo Omeo Annuello Karkarooc Mallee Swan Hill Annya Normanby Hamilton Portland Arapiles Lowan Horsham (P.M.) Arapiles Ararat Borung; Ararat Ararat (City); Ararat, Stawell Ripon Arcadia Moira Benalla Euroa, Goulburn, Shepparton Archdale Gladstone St. Arnaud Bet Bet Ardno Follett Hamilton Glenelg Ardonachie Normanby Hamilton Minhamite Areegra Borug Horsham (P.M.) Warracknabeal Argyle Grenville Ballaarat Grenville, Ripon Ascot Ripon; Ballaarat Ballaarat Talbot Ashens Borung Horsham Dunmunkle Audley Normanby Hamilton Dundas, Portland Avenel Anglesey; Seymour Goulburn, Seymour Delatite; Moira Avoca Gladstone; St. Arnaud Avoca Kara Kara Awonga Lowan Horsham Kowree Axedale Bendigo; Bendigo -

Details Page 9 22 Years for Strathy Murder

Phone 5862 1034 – Fax 5862 2668 – Email - Editorial: [email protected] - Advertising: [email protected] – Registered by Australia Post – Publication No. VA 1548 established 1895 LEADER NumurkahWEDNESDAY, MAY 13, 2020 $1.30 INSIDE Katunga crash A cuppa with Lorna See story page 12& 13 IT was a miracle there were no life-threatening injuries when these two cars collided at Katunga on Sunday morning. See story page 2. 22 years for Restrictions eased - but only a little Strathy murder VICTORIANS are breathing a sigh ing a wedding or funeral. ST THMERTON man Rob- e sentencing judge, Supreme of relief this morning as an easing of ough club rooms will remain ert Strucelj has been sentenced to Court Justice Elizabeth Holling- some COVID-19 restrictions came closed, golfers can again take to the 22 years jail for the murder of Peter worth, ordered that 48 year-old into e ect as of 11.59pm last night. green in groups of four or less, and James Doyle at Strathmerton in Jan- Strucelj serve at least 18 years before ough Victorians are still being shers can cast a line in groups of no uary 2018. being eligible for parole. urged to stay at home for the most more than 10 - once again at a safe so- Numurkah The sentence was handed down Strucelj fatally stabbed 32 year-old part, we are now allowed to have ve cial distance. at the Supreme Court in Sheppar- Mr Doyle, from Bearii, at 1.40am on visitors to those homes at any one Weddings will now be allowed to ton last Friday, almost a year to the January 8, 2018, at a property at Wil- time, and gather in groups of up to 10 consist of the couple plus celebrant gets tested day after Strucelj was found guilty liams Road Strathmerton. -

21.03 Settlement

MOIRA PLANNING SCHEME 21.03 SETTLEMENT 14/12/2017 C77 This clause provides local content to support clause 11 (Settlement) and clause 16 (Housing). 21.03-1 Key issues 14/12/2017 C77 The key planning issues and challenges relating to settlement include: . Facilitating the orderly development of towns and settlements . Facilitating the development of a diverse range of housing options for the existing and future population . Facilitating the sustainable development of small town and settlements . Controlling future development of housing in rural areas to ensure that it is responsive to a demonstrated need and will not prejudice the long-term sustainability of farming An overview of these issues and challenges are described below. 21.03-2 Orderly development of towns and settlements 14/12/2017 C77 Overview Moira Shire is a predominantly rural municipality. Moira has four principal towns (Cobram, Yarrawonga, Numurkah and Nathalia) and a number of smaller towns and settlements that support the rural and lifestyle activities of residents. New residential development is particularly encouraged in these towns so as to attract and support expanding populations that will, in turn, stimulate the economic and social development of these centres. To guide this development Council has completed the following strategic projects to guide the orderly development of its urban areas: . Yarrawonga Strategy Plan 2004 . Cobram 2025 Strategy Plan 2007 . Numurkah Strategy Plan 2010 . Nathalia Strategy Plan 2010 . Moira Small Towns and Settlements Strategy Plan 2013 The Bathumi, Youanmite and Marungi Restructure Plan Report 2008 has restructured areas to provide for the sustainable development of these areas. Council seeks to consolidate residential uses in towns and in surrounding identified rural lifestyle areas, where there is no adverse impact on rural activities.