Mountain West Conference Strategic Scheduling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

June 5, 2020 Commissioner Kevin Warren Big Ten Conference 5440

June 5, 2020 Commissioner Kevin Warren Big Ten Conference 5440 Park Place Rosemont, IL 60018 Dear Commissioner Warren, We are a consortium of advocates for women and girls in sports. Access to and participation in sports improves the lives of all students, and that is particularly true for girls and women. During this time of COVID-19, we are writing to remind you of your institutional obligation to uphold Title IX.1 We understand that these are trying times for collegiate institutions, including athletics departments. In response to financial pressures, we have become aware that some universities are considering program cuts to their athletic programs.2 As the commissioner of the 1 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688. 2 Sallee, Barrett. “Group of Five Commissioners Ask NCAA to Relax Rules That Could Allow More Sports to Be Cut.” CBS Sports, April 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/group-of-five- commissioners-ask-ncaa-to-relax-rules-that-could-allow-more-sports-to-be-cut/. (Five Conferences—American Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA, Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mountain West Conference, and the Sun Belt Conference—formally requested the NCAA to lower the minimum team requirements for Division 1 membership. The NCAA subsequently denied their request.) See also: ⬧ Hawkins, Stephen. “Slashed St. Ed's: Reeling School Cuts Teams, Breaks Hearts.” ABC News. ABC News Network, May 7, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/slashed-st-eds-reeling-school- cuts-teams-breaks-70563956. (Saint Edward's University cuts six varsity teams.); ⬧ Keith, Braden. “After Cuts, Sonoma State Says It Will Add Roster Spots to Comply with Title IX.” SwimSwam, May 1, 2020. -

Summary Letter to Big West Conference Re

June 26, 2020 Commissioner Dennis Farrell Big West Conference 2 Corporate Park Suite 206 Irvine, CA 92606 Dear Commissioner Farrell, We are a consortium of advocates for women and girls in sports. Access to and participation in sports improves the lives of all students, and that is particularly true for girls and women. During this time of COVID-19, we are writing to remind you of your institutional obligation to uphold Title IX.1 We understand that these are trying times for collegiate institutions, including athletics departments. In response to financial pressures, we have become aware that some universities are considering program cuts to their athletic programs.2 As the commissioner of the 1 20 U.S.C. §§ 1681-1688. 2 Sallee, Barrett. “Group of Five Commissioners Ask NCAA to Relax Rules That Could Allow More Sports to Be Cut.” CBS Sports, April 15, 2020. Available at: https://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/group-of-five- commissioners-ask-ncaa-to-relax-rules-that-could-allow-more-sports-to-be-cut/. (Five Conferences—American Athletic Conference (AAC), Conference USA, Mid-American Conference (MAC), Mountain West Conference, and the Sun Belt Conference—formally requested the NCAA to lower the minimum team requirements for Division 1 membership. The NCAA subsequently denied their request.) See also: Hawkins, Stephen. “Slashed St. Ed's: Reeling School Cuts Teams, Breaks Hearts.” ABC News. ABC News Network, May 7, 2020. Available at: https://abcnews.go.com/Sports/wireStory/slashed-st-eds-reeling-school-cuts- teams-breaks-70563956. (Saint Edward's University cuts six varsity teams.); Keith, Braden. -

MOUNTAIN WEST and CONFERENCE USA ANNOUNCE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION Landmark Plan Will Give Members Stability, Exposure and Access

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE OCTOBER 14, 2011 MOUNTAIN WEST AND CONFERENCE USA ANNOUNCE FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION Landmark Plan Will Give Members Stability, Exposure and Access IRVING, Texas/COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. – The Mountain West Conference and Conference USA have unanimously come to an agreement in principle to consolidate their member football programs into one large association. Commissioners of the two leagues formulated this creative and innovative plan with the support of the presidents, chancellors and athletics directors. The 12 members of Conference USA and 10 football‐playing members of the Mountain West will join forces for this strategic landmark in college football. “The role of a conference is to provide its members with the best possible environment in which to conduct their intercollegiate athletics programs,” said Mountain West Commissioner Craig Thompson. “Rather than await changes in membership due to realignment, it became clear the best way to serve our institutions was to pursue an original concept. The Mountain West and C‐USA share a number of similarities, and the creative merger of our football assets firmly positions our respective members for the future.” “The potential of this association is very exciting,” Conference USA Commissioner Britton Banowsky said. “By taking an innovative approach, we feel we can offer tremendous opportunities for exposure and stability without breaking up the regional rivalries that truly make up the college football tradition.” UNLV President and Mountain West Board of Directors Chair Neal Smatresk said, “In an era of uncertainty in intercollegiate athletics, this collaborative partnership with C‐USA lends stability and credibility to our collective football enterprise. We are excited about the prospect of having teams in five time zones and the many possibilities created by this extremely bold and proactive step.” Conference USA Board of Directors Chair and Tulane president Scott Cowen said, “We are very pleased to be moving forward with the Mountain West Conference on this high potential, unique partnership. -

HAWAI'i COLORADO STATE Oct. 29, 2020 Fresno, Calif. UNLV Nov. 7

2020 OPPONENTS HAWAI’I COLORADO STATE UNLV UTAH STATE Oct. 24, 2020 Oct. 29, 2020 Nov. 7, 2020 Nov. 14, 2020 Fresno, Calif. Fresno, Calif. Las Vegas, Nev. Logan, Utah General Information General Information General Information General Information Location ........................Honolulu, Hawai’i Location ........................Fort Collins, Colo. Location ............................ Las Vegas, Nev. Location ..................................Logan, Utah Founded ................................................1907 Founded ................................................1870 Founded ................................................1957 Founded ................................................1888 Enrollment ....................................... 18,000 Enrollment ....................................... 33,877 Enrollment ....................................... 31,142 Enrollment ....................................... 27,810 Nickname .....................Rainbow Warriors Nickname ........................................... Rams Nickname ..........................................Rebels Nickname .........................................Aggies Colors ......Green, Black, White and Silver Colors ...............................Green and Gold Colors ...............................Scarlet and Gray Colors ........ Navy Blue, White and Pewter Gray Affiliation........... NCAA Division I - FBS Affiliation........... NCAA Division I - FBS Affiliation........... NCAA Division I - FBS Affiliation........... NCAA Division I - FBS Conference ........................Mountain -

Combined Guide for Web.Pdf

2015-16 American Preseason Player of the Year Nic Moore, SMU 2015-16 Preseason Coaches Poll Preseason All-Conference First Team (First-place votes in parenthesis) Octavius Ellis, Sr., F, Cincinnati Daniel Hamilton, So., G/F, UConn 1. SMU (8) 98 *Markus Kennedy, R-Sr., F, SMU 2. UConn (2) 87 *Nic Moore, R-Sr., G, SMU 3. Cincinnati (1) 84 James Woodard, Sr., G, Tulsa 4. Tulsa 76 5. Memphis 59 Preseason All-Conference Second Team 6. Temple 54 7. Houston 48 Troy Caupain, Jr., G, Cincinnati Amida Brimah, Jr., C, UConn 8. East Carolina 31 Sterling Gibbs, GS, G, UConn 9. UCF 30 Shaq Goodwin, Sr., F, Memphis 10. USF 20 Shaquille Harrison, Sr., G, Tulsa 11. Tulane 11 [*] denotes unanimous selection Preseason Player of the Year: Nic Moore, SMU Preseason Rookie of the Year: Jalen Adams, UConn THE AMERICAN ATHLETIC CONFERENCE Table Of Contents American Athletic Conference ...............................................2-3 Commissioner Mike Aresco ....................................................4-5 Conference Staff .......................................................................6-9 15 Park Row West • Providence, Rhode Island 02903 Conference Headquarters ........................................................10 Switchboard - 401.244-3278 • Communications - 401.453.0660 www.TheAmerican.org American Digital Network ........................................................11 Officiating ....................................................................................12 American Athletic Conference Staff American Athletic Conference Notebook -

Women's Soccer Conference Standings

WOMEN’S SOCCER CONFERENCE STANDINGS 2019 Division I Conference Standings 2 2019 Division II Conference Standings 6 2019 Division III Conference Standings 10 All-Time Division I Conference Champions 16 2019 DIVISION I CONFERENCE STANDINGS America East Conference Atlantic 10 Conference Conference Full Season Conference Full Season Team W L T Pct. W L T Pct. Team W L T Pct. W L T Pct. Stony Brook# 6 1 1 .813 14 6 1 .690 Saint Louis# 9 0 1 .950 17 4 2 .783 Albany (NY) 6 1 1 .813 9 6 3 .583 George Washington 7 1 2 .800 14 3 4 .762 Hartford 5 2 1 .688 10 7 2 .579 Massachusetts 6 3 1 .650 10 6 3 .605 New Hampshire 5 3 0 .625 10 8 0 .556 La Salle 6 4 0 .600 11 8 1 .575 Binghamton 4 3 1 .563 10 6 2 .611 Dayton 5 3 2 .600 7 9 3 .447 UMass Lowell 3 4 1 .438 4 11 2 .294 Fordham 4 4 2 .500 5 11 4 .350 Vermont 1 6 2 .222 3 10 3 .281 Duquesne 4 5 1 .450 6 8 3 .441 Maine 1 6 1 .188 5 8 1 .393 Saint Joseph’s 4 5 1 .450 7 10 2 .421 UMBC 1 7 0 .125 2 13 2 .176 Richmond 4 6 0 .400 7 9 2 .444 VCU 3 5 2 .400 9 6 3 .583 American Athletic Conference Davidson 3 5 2 .400 8 8 3 .500 Conference Full Season St. -

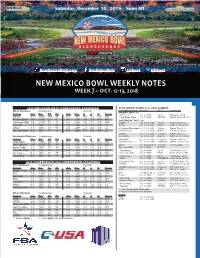

Week 7 – Oct. 13, 2018

NewMexicoBowl.com NewMexicoBowl nmbowl NMbowl NEW MEXICO BOWL WEEKLY NOTES WEEK 7 ~ OCT. 12-13, 2018 2018 MOUNTAIN WEST CONFERENCE STANDINGS THIS WEEK’S MW & C-USA GAMES West Division Conference Overall Game [#AP/Coaches] Records MT/TV Series Notes FRIDAY, OCT. 12 School W-L Pct. PF PA W-L Pct. H A N Streak ^ Air Force 2-3, 0-2 MW 7 p.m. AF leads, 19-16 Hawai`i 3-0 1.000 104 88 6-1 .857 4-0 2-1 0-0 W3 ^ San Diego State 4-1, 1-0 MW CBSSN SDSU, 28-24 (2017) Fresno State 1-0 1.000 21 3 4-1 .800 2-0 2-1 0-0 W3 SATURDAY, OCT. 13 San Diego State 1-0 1.000 19 13 4-1 .800 3-0 1-1 0-0 W4 ¢ UAB 4-1, 2-0 C-USA 11 a.m. Series Tied, 3-3 Nevada 1-1 .500 31 46 3-3 .500 2-1 1-2 0-0 L1 ¢ Rice 1-5, 0-2 C-USA ESPN+ UAB, 52-21 (2017) UNLV 0-1 .000 14 50 2-3 .400 2-1 0-2 0-0 L2 ¢ Southern Mississippi 2-2, 1-0 C-USA 12 p.m. Series Tied, 6-6 San José State 0-2 .000 71 86 0-5 .000 0-3 0-2 0-0 L5 ¢ North Texas 5-1, 1-1 C-USA ESPN3 NT, 43-28 (2017) ¢ WKU 1-4, 0-1 C-USA 1:30 p.m. WKU leads, 1-0 Mountain Division Conference Overall ¢ Charlotte 2-3, 1-1 C-USA ESPN+ WKU, 45-14 (2017) School W-L Pct. -

Sports Analytics from a to Z

i Table of Contents About Victor Holman .................................................................................................................................... 1 About This Book ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction to Analytic Methods................................................................................................................. 3 Sports Analytics Maturity Model .................................................................................................................. 4 Sports Analytics Maturity Model Phases .................................................................................................. 4 Sports Analytics Key Success Areas ........................................................................................................... 5 Allocative and Dynamic Efficiency ................................................................................................................ 7 Optimal Strategy in Basketball .................................................................................................................. 7 Backwards Selection Regression ................................................................................................................... 9 Competition between Sports Hurts TV Ratings: How to Shift League Calendars to Optimize Viewership ................................................................................................................................................................. -

THE BIG SKY CONFERENCE CONFERENCE the Big Sky Conference Enters Its 57Th Year and 31St Gave the League Eight Members

LEAGUE INFORMATION ANNUAL BIG SKY THE BIG SKY CONFERENCE CONFERENCE The Big Sky Conference enters its 57th year and 31st gave the league eight members. The Big Sky Conference FOOTBALL year of women’s competition during the 2019-20 academic conference grew to Football Members CHAMPIONS year. nine schools in 1987 with the addition UC Davis Cal Poly Four of the current league members – Idaho State of Eastern Washington. 1963: Idaho State Eastern Washington 1964: Montana State University, The University of Montana, Montana State and The 1990s saw change in the Idaho Weber State – have been with the league since its birth. makeup of the league, beginning in Idaho State 1965: Weber State, Idaho Northern Arizona University enters its 50th season in 1992 when Nevada departed and put Montana 1966: Montana State the league, giving the league five members with at least 50 the Big Sky back at eight teams. In Montana State 1967: Montana State years of continuous membership. 1996 Boise State and Idaho left and at Northern Arizona 1968: Weber State, Montana State, Northern Colorado Idaho Fellow charter member the University of Idaho the same time the conference added Portland State 1969: Montana returned most of its sports to the Big Sky on July 1, 2014, Portland State, Sacramento State and Sacramento State 1970: Montana then its football program moved from the FBS level to FCS in Cal State Northridge. The Big Sky main- Southern Utah 1971: Idaho 2018, rejoining the Big Sky Conference. tained nine teams for five years before Weber State 1972: Montana State North Dakota left the Big Sky Conference following the Cal State Northridge departed in the 1973: Boise State 2017-18 academic year. -

Department of Intercollegiate Athletics

Department of Intercollegiate Athletics (White Paper Analysis - 2011) Introduction This is an update to the our 2009 white paper. It includes information regarding contingency plans for possible operating budget reductions at 2%, 5% and 8% levels and the expense areas that might be affected. Our percentage reductions are based on our full Section I distribution of $11,353,932. We do believe, however, that the more accurate calculation should be taken from our Section I distribution minus our Obligation to the General Fund ($2,379,044). Since we must pay back the Obligation to the General Fund, planning for budget reductions using this number causes Intercollegiate Athletics to reduce expenses based on an “inflated” Section I funding amount. Here is how the 2%, 5% and 8% budget reduction amounts calculate…with Obligation to the General Fund included compared to the amount when it is not included: SECTION I (With Obligation included) SECTION I (Without Obligation) $11,353,932 TOTAL $8,974,888 TOTAL $227,079 2% Reduction $179,498 2% Reduction $567,697 5% Reduction $448,744 5% Reduction $908,315 8% Reduction $717,991 8% Reduction FINANCIAL/ORGANIZATIONAL OVERVIEW From a budget perspective, the University of Wyoming Intercollegiate Athletics program ($26 million) remains at or near the bottom (8th or 9th …out of nine schools) in the Mountain West Conference. The conference institutions which we compete against are Air Force, Boise State , Colorado State, Fresno State, Nevada, New Mexico, San Diego State,, UNLV and Hawaii (football only). The UW Intercollegiate Athletic budget is made up of approximately 40% Section I (State) funding and 60% Section II (self generated) funding. -

NCAA Division I Academic Performance Program

INFORMATIONAL ITEMS OF THE NCAA DIVISION I COMPETITION OVERSIGHT COMMITTEE OCTOBER 5, 2020, VIDEOCONFERENCE Note: This document does not include items incorporated in the NCAA Division I Council report. INFORMATIONAL ITEMS. 1. Review of recent reports. The NCAA Division I Competition Oversight Committee approved reports from its June quarterly meeting and subsequent biweekly videoconferences through September 23. 2. Equity, diversity, inclusion (EDI) and the student-athlete voice. Staff updated the committee on initiatives the Championships Equity Action Team is undertaking that enhance opportunities to support equity, diversity and inclusion at NCAA championships. 3. Division I governance update. Staff updated the committee on the work being conducted by the NCAA Name, Image and Likeness Legislative Solutions Group, the NCAA Division I Championships Finance Review Working Group, and the NCAA Division I Working Group on Transfers, all three of which are finalizing legislative packages for the NCAA Division I Council to consider for the 2020-21 cycle. 4. Financial status report. The committee reviewed budget-to-actuals for championships through the 2019-20 fiscal year. 5. COVID-19 updates. a. Update from NCAA Chief Medical Officer. NCAA Chief Medical Officer Dr. Brian Hainline updated the committee on the recently released resocialization policies for basketball and additional efforts being taken to address participant health and safety and testing protocols in other sports. b. Governance meetings. Staff noted that governance meetings will be held virtually through August 2021, though there may be limited exceptions for championship selection meetings. 6. Playing Rules Oversight Panel reports. The committee reviewed reports from the panel's most recent meetings. -

2006 Mountain West Conference Football Media Guide

2006 MOUNTAIN WEST CONFERENCE FOOTBALL MOUNTAIN WEST CONFERENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS 15455 Gleneagle Drive, Suite 200 Colorado Springs, CO 80921 Media Relations Directory . .2 www.TheMWC.com Media Services . .3 Mountain West Conference Demographics . .4 Mountain West Conference Chronology . .5 Mountain West Conference History . .6-7 MWC COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Commissioner Craig Thompson . .8 Mountain West Conference Staff . .9 Javan Hedlund Mountain West Conference Championships . .10 Asst. Commissioner for Communications Mountain West Conference Student-Athlete of the Year/Sportsmanship Awards . .11 (719) 488-4051/C (719) 648-4027 Football Stadium Directions . .12 Officials and Rule Changes . .13 [email protected] MWC Instant Replay . .14 Marlon Edge Assistant Director of Communications Conference Notes (719) 488-4052/C (719) 339-1558 2006 Preseason Notes . .16-18 2006 Preseason Team Capsules . .19 [email protected] Television Information . .20-21 BCS & Pioneer PureVision Las Vegas Bowl . .22 Becky Motchan Poinsettia, Fort Worth, New Mexico & Houston Bowls . .23 Assistant Director of Communications 2006-07 College Bowl Schedule . .24 (719) 488-4046/C (314) 853-6487 [email protected] Team Previews Air Force . .25-31 Lauri Pyatt BYU . .32-37 Multi-Media Coordinator Colorado State . .38-43 (719) 488-4059 New Mexico . .44-49 [email protected] San Diego State . .50-55 TCU . .56-61 UNLV . .62-67 Utah . .68-73 Wyoming . .74-79 CREDITS The Mountain West Conference 2006 Football Season Review Media Guide was produced by the MWC 2005 Season Review . .82-83 communications staff using Microsoft Word and 2005 All-Mountain West Conference Honors . .84 QuarkXPress. Written and edited by Javan Hedlund. 2005 Academic All-Mountain West Conference .