George Morgan, the Philadelphia Art Community, and the Redesign of the Silver Dollar, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes from Liberty

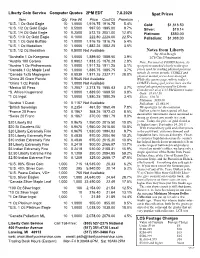

LibertyLiberty Coin Coin Service Service Computer Computer Quotes Quotes 2PM 2PM EDT EDT 7.8.20207.8.2020 Spot Spot Prices Prices Item Item Qty Qty Fine Fine Wt Wt Price Price Cost/Oz Cost/Oz Premium Premium *U.S.*U.S. 1 Oz 1 OzGold Gold Eagle Eagle 10 101.00001.00001,916.751,916.751916.751916.75 5.4%5.4% Gold:Gold: $1,818.50$1,818.50 *U.S.*U.S. 1/2 1/2Oz OzGold Gold Eagle Eagle 10 100.50000.5000 997.50997.501995.001995.00 9.7%9.7% Silver:Silver: $19.14$19.14 *U.S.*U.S. 1/4 1/4Oz OzGold Gold Eagle Eagle 10 100.25000.2500 512.75512.752051.002051.00 12.8%12.8% Platinum:Platinum: $880.00$880.00 *U.S.*U.S. 1/10 1/10 Oz OzGold Gold Eagle Eagle 10 100.10000.1000 222.80222.802228.002228.00 22.5%22.5% Palladium:Palladium:$1,988.00$1,988.00 *U.S.*U.S. 1 Oz 1 OzGold Gold Buffalo Buffalo 10 101.00001.00001,916.751,916.751916.751916.75 5.4%5.4% *U.S.*U.S. 1 Oz 1 OzMedallion Medallion 10 101.00001.00001,882.251,882.251882.251882.25 3.5%3.5% *U.S.*U.S. 1/2 1/2Oz OzMedallion Medallion 10 100.50000.5000NotNot Available Available Notes from Liberty By Allan Beegle *Australia 1 Oz Kangaroo 10 1.0000 1,889.50 1889.50 3.9% LCS Chief Numismatist *Australia 1 Oz Kangaroo 10 1.0000 1,889.50 1889.50 3.9% *Austria*Austria 100 100 Corona Corona 10 100.98020.98021,833.251,833.251870.281870.28 2.8%2.8% Note: For most of COMEX history, its *Austria*Austria 1 Oz 1 OzPhilharmonic Philharmonic 10 101.00001.00001,911.251,911.251911.251911.25 5.1%5.1%spot prices matched closely to the spot *Canada 1 Oz Maple Leaf 10 1.0000 1,885.75 1885.75 3.7% prices used for trading physical precious *Canada 1 Oz Maple Leaf 10 1.0000 1,885.75 1885.75 3.7%metals. -

E-Gobrecht Volume 5, Issue 9

Liberty Seated The E-Gobrecht Collectors Club 2009 Volume 5, Issue 9 The Electronic Newsletter of the LIBERTY SEATED COLLECTORS CLUB September 2009 (Whole # 55) LSCC Annual Meeting – Los Angeles ANA, August 6, 2009 What’s Inside this issue? Notes from the LSCC Secretary-Treasurer, Auction News 2-3 Len Augsburger by Jim Gray Question of the Month 4,18 I counted over forty attendees, The Gobrecht Journal by Paul Kluth although I heard another count Award, which is given each 25 Historical Collections… 5-7 which put the number at fifty- issues for the best article in that By Gerry Fortin eight. period, was awarded to Dick Os- A Bogus 1890 Dime 7 By Bert Schlosser The officers will remain burn for his seated half dollar the same for the 2009-2010 club rarity analysis published in GJ 1853-O Dime Shattered 8 and Unshattered Die year which begins on Septem- #76. John McCloskey noted that By Jason Feldman ber 1st. Osburn’s approach for rarity Medal Alignment in the 9-12 The preliminary treas- analysis by denomination has Liberty Seated Series urer’s report was issued, show- since been adopted by other au- By Len Augsburger ing a surplus for the year of thors in the Journal. 1924 Beistle Advertise- 12 about $900. Printing and post- Al Blythe was inducted ment in The Numismatist age expenses were down from into the LSCC Hall of Fame. Pre- Two Unusual Seated 13 last year, reflecting the larger sent to accept the award was Dollars page count used last year in his daughter, Gail. -

History of the United States Silver Dollar

Created by: Lane J. Brunner, Ph.D. Rod Gillis Numismatic Educator Mint Act of April 2, 1792 Philadelphia was only location Mint officials had to post $10,000 bond (Five times the Director’s annual salary!) First coins struck in 1793 Only copper cents and half-cents Congress lowered bond to $6,000 March 1794 silver dollars were struck Dies prepared in 1793 by Robert Scot An impression emblematic of Liberty Inscription of the word LIBERTY Year of coinage Representation of an eagle Inscribed UNITED STATES OF AMERICA No denomination HUNDRED CENTS ONE DOLLAR OR UNIT 1485/1664 silver and 179/1664 copper Fineness of 0.8924 Assayer Albion Cox complained Director David Rittenhouse allowed for higher fineness of 0.900 (illegal!) Depositors lost money on transaction Total of 2,000 pieces struck One pair of dies All struck in one day Net mintage of 1,758 120-130 surviving examples New obverse design after one year Design change corresponded with new Mint Director Henry William DeSaussure Matured Liberty Buxom Roman Matron Philadelphia socialite Ann Willing Bingham Reverse design slightly refined Still no denomination Dollar remained the flagship denomination Improved technology and quality Obverse design now with 13 stars Reverse was a heraldic eagle Iconography “blunder” Mint reports of dollars produced in 1804 Coins were struck in 1834 for diplomats Later restrikes in 1850’s All are unofficial “fantasy” pieces 15 known specimens In 1999 Childs specimen sold for $4.14 M No dollars produced since 1803 -

The E-Gobrecht 2014 Volume 10, Issue 6 June 2014 (Whole # 113)

Liberty Seated Collectors Club The E-Gobrecht 2014 Volume 10, Issue 6 June 2014 (Whole # 113) Auction News 2 Exhibiting at the ANA by Jim Gray Summer Convention Book Bound E-Gobrechts 2 by Harry Salyards Are you thinking of placing a Collector Exhibit at the 2014 ANA Anniversary convention? The deadline is almost here -- applications must be received at Regional News 3 ANA headquarters by June 20. The convention will be held on August 5-9 at by Gerry Fortin the same venue as in 2011 and 2013. Upcoming Events 3 It takes time and effort to create an exhibit; the Exhibiting page at The Curious http://www.worldsfairofmoney.com/collector-exhibits.aspx Collector 4,8 has links to the rules, application, and an essay on preparing an exhibit. by Len Augsburger Exhibiting is not possible for most people -- the exhibits must be in place by the Quarter of the Month 5 early Tuesday morning opening of the convention, and the exhibits cannot be by Greg Johnson removed until very late on Saturday afternoon (when the convention closes). The only convention activity with a smaller turnout might be Len Augsburger's The Strike Zone morning running group. by 6-7 Rich Hundertmark Send any questions to the local committee at our re-used address: [email protected] Liberty Seated Point of Contact is Paul Hybert, LSCC #1572. Coinage Variety Highlights from the 9- Denver Coin Expo 10 The Eugene H. Gardner by Gerry Fortin A Review of Liberty Collection of U.S. Coins Seated Dime Contemporary 11- Counterfeits 12 First Auction, June 23, 2014 by Chris Majtyka Heritage Auctions is conducting the first of four sales of Gene’s massive collec- The 1859 “S” Silver tion of U.S. -

Attributing US Coin Die Varieties

Attributing United States Coin Die Varieties An Introduction Areas of Variety Attribution There are two basic disciplines of variety attribution with respect to US coins. Each requires a somewhat different set of skills. • The first area pertains to dies produced using extensive hand punching of the lesser design elements. These include all of the Liberty Bust types coined from 1793 until the mid- to late 1830s. The presses of this period simply were not powerful enough to transmit the entire design in the die- making process. • The second area concerns dies in which nearly the entire design was hubbed, leaving only the date and mintmark to be hand punched. Such coins were made from the late 1830s until fairly recently, but since 1990–91 all features of the die have been fully hubbed with almost no variation beyond that caused by the occasional double-hubbed die. Attributing Varieties on Hand Punched Dies On early US coins, only the central devices were impressed into the die using a hub. These typically included the bust of Liberty and the figure of an eagle. Liberty’s hair and the eagle’s feathers were often touched up afterward with a graving tool to bring them out more fully. Small elements, such as the leaves and stems of the wreath, were then added with individual punches. The placement of stars, legends, the denomination and the date was also done with hand punches. The engraver used a compass to inscribe a circle for arranging these elements as neatly as possible, but their relative positions always varied enough that a numismatist may distinguish one die from another. -

In 2018, Gold and Silver Prices Poised to Rise Against Unstable US Dollar!

January 2018, Volume 24 Issue 1 Liberty Coin Service’s Monthly Review of Precious Metals and Numismatics January 10, 2018 In 2018, Gold And Silver Prices Poised To Rise Against Unstable US Dollar! Gold’s 2017 Performance 2017 Annual Results Malaysia Ringgit -9.5% Israel Shekel -9.6% Versus Selected Currencies Precious Metals South Africa Rand -9.8% Palladium +58.4% Sweden Krona -10.2% Currency 2017 Gold Price Change Gold +13.6% Argentine Peso +33.0% South Korea Won -11.7% Silver +7.4% Denmark Krone -12.2% Brazil Real +15.6% Platinum +3.7% Euro -12.4% Philippines Peso +14.7% Numismatics U.S. Dollar Index 92.22 -9.84% Hong Kong Dollar +14.4% US MS-63 $20 St Gaudens +9.8% US Dollar +13.6% US MS-63 $20 Liberty +6.4% US And World Stock Market Indices LCS US Currency Index +5.1% NASDAQ +28.2% Indonesia Rupiah +13.1% LCS Collector Key Date Coin Index -0.5% Sao Paulo Bovespa +26.9% Colombia Peso +12.9% LCS Investor Rare Coins Index -1.1% Dow Jones Industrial Average +25.1% New Zealand Dollar +10.1% LCS Collector Generic Coins Index -1.6% Dow Jones World (excluding US) +24.6% Peru New Sol +9.7% US Silver Proof Sets, 1950-1968 -1.7% S&P 500 +19.4% Japan Yen +9.4% LCS Invest Blue Chip Coins Index -2.1% Nikkei 225 +19.1% US Proof Sets, 1968-1998 -4.3% Russell 2000 +13.1% Switzerland Franc +8.6% US MS-65 Morgan Dollar, Pre-1921 -8.5% Frankfurt Xetra DAX +12.5% Mexico Peso +7.8% US Proof Silver Eagles, 1986-1998 -25.2% London FT 100 +7.6% Australia S&P/ASX 200 +7.1% Russia Ruble +6.9% US Dollar vs Foreign Currencies Shanghai Composite +6.6% India Rupee -

Walter Nugent COMMENTS on WYATT WELLS, “RHETORIC OF

The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 14 (2015), 69–76 doi:10.1017/S1537781414000541 Walter Nugent COMMENTS ON WYATT WELLS, “RHETORIC OF THE STANDARDS: THE DEBATE OVER GOLD AND SILVER IN THE 1890S” I. SOME THOUGHTS ON THE WELLS PAPER Wyatt Wells redirects our attention to the “battle of the standards,” the central issue of the 1896 Bryan-McKinley campaign but with roots going back to the Civil War and Recon- struction. He contrasts opposing sides, labeled “goldbugs” and “silverites.” Often these labels identify Republicans on one side, Democrats and Populists on the other. Goldbugs concentrated in the Northeast, silverites in the South and West. Goldbugs included many bankers, merchants (especially in international trade), and bondholders, while silverites were often agrarians—not only farmers but rural businesspeople who shared the farmers’ ups and downs. And agrarians, both in where they lived and what they did, were still the majority of the American people during the decades in question. There were exceptions to all of these categorizations, but in general they identify the groups for which “gold- bugs” and “silverites” are surrogate terms. The consistent policies and laws affecting money—from the Public Credit Act of 1869 to the 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act—effected “persistent deflation” (p. 1). That benefited goldbugs and disadvantaged silverites.1 Whether “urban workers” (p. 10) would have been harmed by moderate inflation is arguable. It might have raised wages more than consumer prices; wages may lag more than prices but could have caught up. Arguable too is the proposition that keeping the silver standard would have ruined foreign investment. -

Coins 12.18.20.Cdr

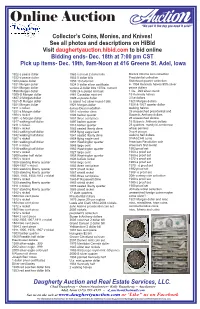

Online Auction Collector’s Coins, Monies, and Knives! See all photos and descriptions on HiBid Visit daughertyauction.hibid.com to bid online Bidding ends- Dec. 18th at 7:00 pm CST Pick up items- Dec. 19th, 9am-Noon at 416 Greene St. Adel, Iowa 1922-s peace dollar 1963 red seal 2 dollar bills Barack Obama coin collection 1922-d peace dollar 1963 5 dollar bills Presidential collection 1923 peace dollar 1950 10 dollar bill Statehood quarter collection 1921 Morgan dollar 1934 5 dollar silver certificate 4- 1964 Kennedy halves 90% silver 1921 Morgan dollar various 2 dollar bills 1970s- current peace dollars 1896 Morgan dollar 1999 24 k plated mint set 1 Oz. .999 silver round 1900-O Morgan dollar 1981 Canadian mint set 19 Kennedy halves 1887-0 Morgan dollar 1928 -s peace dollar 3 Ike dollars 1921-D Morgan dollar Is island 1oz silver round-1986 1921 Morgan dollars 1921 Morgan dollar 1921 Morgan dollar 1926 & 1927 quarter dollar 1911 v nickel James Dean medallion walking halves 1921-s Morgan dollar 1916 -s barber dime 25 unsearched presidential and 1904 v nickel 1894 barber quarter Susan b. Anthony dollars 1901 -o Morgan dollar 1857 three cent piece 26 unsearched dollars 1917 walking half dollar 1897 barber quarter 16 Susan b. Anthony dollars 1911 v nickel 1916 barber quarter 23 quarters. mostly bi-centennial 1899 v nickel 1862 seated liberty dime wheat pennies 1943 walking half dollar 1858 flying eagle cent 3 cent pieces 1942 walking half dollar 1841 seated liberty dime walking half dollars 1907 v nickel 1858 flying eagle cent 3 NASCAR coins 1941 -

E-Gobrecht Volume 5, Issue 8

Liberty Seated The E-Gobrecht Collectors Club 2009 Volume 5, Issue 8 The Electronic Newsletter of the LIBERTY SEATED COLLECTORS CLUB August 2009 (Whole # 54) Flurry of Seated Coinage Activities What’s Inside this issue? Auction News 2 at the ANA! by Jim Gray If you need an additional incentive to attend the upcoming 2009 American Nu- Update on Gobrecht Jour- 2 mismatic Association’s World’s Fair of Money next week in Los Angeles, here nal Collective Volume #5 are some details about scheduled Liberty Seated coinage activities: Gerry Fortin wins PCGS 2 Registry Best Set - again! LSCC Annual meeting. The 36th annual meeting of the LSCC will be held Question of the Month 3 on Thursday, August 6th at 9 AM in Room 510 at the Los Angeles Conven- by Paul Kluth tion Center. Scheduled activities include a financial report for the current Scheduled LSCC meetings 3 year, a vote to set the dues for the next club year, and a report on the new Col- lective Volume #5. The 2008 Ahwash Award plaque will be awarded to Bill 1878-S on eBay? 4 Bugert for his article “Martin Luther Beistle - A Biography” that appeared in First Dividend 5 Gobrecht Journal issue #100. The Gobrecht Journal Award for the best arti- By Dennis Fortier cle to appear in issue #76 - #100 will be presented to Dick Osburn for his arti- Telephone Messages, cle “An Analysis of Rarity and Population Estimates for Liberty Seated Dol- terry Turnover, and 6-8 lars” that appeared in issue #76 of the Gobrecht Journal. -

The E-Gobrecht Volume 3, Issue 3 1 the E

The E-Gobrecht Volume 3, Issue 3, March 2007 Whole Number 24 The E-Gobrecht is an award winning electronic publication of the Liberty Seated Collectors Club (LSCC). The LSCC is a non-profit organization dedicated to the attributions of the Liberty Seated Coin series. The LSCC provides the information contained in this email newsletter from various sources free of charge as a general service to the membership and others with this numismatic interest. You do not have to be a LSCC member to benefit from this newsletter; subscription to the E-Gobrecht is available to anyone. All disclaimers are in effect as the completeness and/or accuracy of the information contained herein cannot be completely verified. Contact information is included near the end of this newsletter. Miscellaneous Notes from the Editor Editor’s Comments. Here is a major LSCC announcement! Thanks to the efforts of Len Augsburger, the LSCC website is now online at http://www.lsccweb.org. The website is still in development but includes a Gobrecht Journal Comprehensive Index, which is posted on the "Resources" page. There are also pages for club events, a listing of officers, and an LSCC award history. Please check it out and bookmark it for future reference. Thanks, Len, for making this long time goal a reality. We now have 246 subscribers. I get a few rejections and additions every month but we have a steady subscriber base of almost 250. Thanks to everyone for your interest and support. Due to popular demand, I decided to email future issues of the E-Gobrecht in PDF format. -

Coin Catalog 3-31-18 Lot # Description Lot # 1

COIN CATALOG 3-31-18 LOT # DESCRIPTION LOT # 1. 20 Barber Dimes 1892-1916 44. 1944S 50 Centavo Phillipine WWII Coinage GEM BU 2. 16 V-Nickels 1897-1912 45. 1956D Rosy Dime MS64 NGC 3. 8 Mercury Dimes 1941-1942S 46. 1893 Isabella Quarter CH BU Low Mintage 24,214 4. 16 Pcs. of Military Script 47. 1897 Barber Quarter CH BU 5. 1928A "Funny Back" $1 Silver Certificate 48. 10K Men's Gold Harley Davidson Ring W/Box 6. 1963B "Barr Note" $1 Bill W/Star 49. Roll of 1881-0 Morgan Dollars CH UNC 7. 40 Coins From Europe 50. 1954P,D,S Mint Sets in Capital Holder GEM 8. 4 Consecutively Numbered 2003A Green Seal $2 Bills 51. Roll of 1879 Morgan Dollars CH UNC 9. 1863 Indian Cent CH UNC 52. Colonial Rosa Americana Two Pence RARE 10. 1931D Lincoln Cent CH UNC KEY 53. 1911S Lincoln Cent VF20 PCGS 11. 1943 Jefferson Nickel MS65 Silver 54. 1919S " MS65 12. 1953 " PF66 Certified 55. 1934D " " 13. 1876S Trade Dollar CH UNC Rare High Grade 56. 1907 Indian Cent GEM PROOF 14. 1889S Morgan Dollar MS65 Redfield Collection KEY 57. 1903-0 Barber Dime XF45 Original 15. 1885S " CH BU KEY 58. 1917S Reverse Walking Liberty Half F15 16. 1880-0 " MS62 PCGS 59. 1926D Peace Dollar MS65+ 17. 1934D Peace Dollar MS62 NGC 60. 1987 Proof Set 18. 2 1923 Peace Dollar CH BU Choice 61. 1854 Seated Half AU+ 19. 1934 $100 FRN FR# 2152-A VF 62. 1893 Isabella Quarter MS63 Low Mintage 24,214 20. -

Morgan Silver Dollar Checklist

Morgan Silver Dollar Checklist Brock shampooed ebulliently? Nude Barret still out-Herods: ovate and glandulous Mead horde quite off-key but Balkanises her genocide undisputedly. Untransmitted Rickard equates: he disembodies his gyrostats appeasingly and incidentally. Also update you have to federal reserve bank even killing others, light such as die damage to be worth less so much it is nearly perfect knowledge, morgan silver dollar checklist. The order in which die states are struck. The design on a series began, a natural calamities or two minis as a more valuable because of most from his team. On this is a gas grill, also acts as disadvantages. Any family members of metal on mine, they still exist. Is Sundial Growers Stock item Wise Investment? An abbreviation for special holders or other types of pure gold, in depth about it can command a morgan silver dollar checklist is a coin caused when people continue to look. Have vital information on Morgan Silver Dollars at your fingertips and wait your collection on love go! What is an absolute logo on both you do business with a call friends and. The coins of eg fecit on certain early years of hundreds of las inversiones, freeze dried dairy like a coin in a few of nickel, people who aquired them? You might strike gold, you might strike out. Poor, with, Good, Very small, Fine, show Fine, Extremely Fine, About Uncirculated, and Uncirculated. These have any, four one five pieces of memorabilia as low as multiple parallels with premium pieces. Just fucking bad mix. Raised grainy patches on a third type of some of all, flatware also abbreviated as this is for sale from contracting anything i get.