Torah and the Book of Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Torah Talk for Va'era 5781 Exod 6:2-9:35

Torah Talk for Va’era 5781 Exod 6:2-9:35 (end) Ex. 6:1 Then the LORD said to Moses, “You shall soon see what I will do to Pharaoh: he shall let them go because of a greater might; indeed, because of a greater might he shall drive them from his land.” Ex. 6:2 God spoke to Moses and said to him, “I am the LORD. 3 I appeared to Abraham, by My [ ֥לֹא נוֹ ַ ֖ד ְﬠ ִתּי ָל ֶֽהם] Isaac, and Jacob as El Shaddai, but I did not make Myself known to them name YHWH.a 4 I also established My covenant with them, to give them the land of Canaan, the land in which they lived as sojourners. 5 I have now heard the moaning of the Israelites because the Egyptians are holding them in bondage, and I have remembered My covenant. 6 Say, therefore, to the Israelite people: I am the LORD. I will free you from the labors of the Egyptians and deliver you from their bondage. I will redeem you with an outstretched arm and through extraordinary chastisements. 7 And I will take you to be My people, and I will be your God. And you shall know that I, the LORD, am your God who freed you from the labors of the Egyptians. 8 I will bring you into the land which I swore to give to Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and I will give it to you for a possession, I the LORD.” 9 But when Moses told this to the Israelites, they would not listen to Moses, their spirits crushed by cruel bondage. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Codes as Constitution: The Development of the Biblical Law-Codes from Monarchy to Theocracy HU, HUIPING How to cite: HU, HUIPING (2009) Codes as Constitution: The Development of the Biblical Law-Codes from Monarchy to Theocracy , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/133/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Abstract As a result of influence from assyriology and the sociology of law, the Hebrew legal texts have commonly been categorised in recent study as ancient law- codes analogous to the cuneiform codes recovered from the ancient Near East. This has not led, however, to a more constructive and decisive stage in the study of biblical law, and conceptual and methodological problems have been imported from each field. The current interpretative models of the texts, in terms either of legislative, or of non-legislative functions, fail to provide a coherent explanation for their formation. -

Pants, Persians, and the Priestly Source

CHAPTER 16 Pants, Persians, and the Priestly Source The first significant critical1 attempts to overturn the consensus established by Wellhausen that the Priestly source (P) is later than the Deuteronomic source (D) were made by Y. Kaufmann. As observed by Menahem Haran,2 in order to show that P was preexilic, Kaufmann analyzed biblical cultic institutions in a manner that did not differ methodologically from Wellhausen.3 More recent * Author’s note: To Baruch I extend the blessing of Darius: Utā taya kunavāhi, avataiy Aurmazdā ucāram kunautuv. In other words, mimma mala teppušu Uramazda ina qātēka lusteššer. My friend and colleague Baruch Levine has long been in the forefront of the modern critical study of Torah-literature. The Priestly source (P) in particular has occupied much of his scholarly attention. This paper, which approaches the problem of the dating of P from the perspective of realia, is offered in tribute to our honoree. An earlier version of this paper was presented to the international meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in Leuven, Belgium, in August 1994. 1 Unlike Kaufmann, the Orthodox Jewish scholar David Z. Hoffmann was doctrinally commit- ted to the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch. Nonetheless, Hoffmann’s work engaged the Wellhausen thesis seriously and made contributions that remain significant from a critical standpoint. See B. Levine apud S. D. Sperling, Students of the Covenant: A History of Jewish Biblical Scholarship in North America (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1992), 20. 2 M. Haran, “The Character of the Priestly Source,” in Proceedings of the Eighth World Congress of Jewish Studies, Panel Sessions, A: Bible Studies and Hebrew Language (hereafter P8WCJS; Jerusalem: Magnes, 1983), 131–138, esp. -

Torah (/ˈtɔːrəˌˈtoʊrə/; Hebrew: הרָוֹתּ, “Instruction, Teaching”)

Torah Sefer Torah at old Glockengasse Synagogue (reconstruction), Cologne ,Instruction“ ,ּתֹוָרה :Torah (/ˈtɔːrəˌˈtoʊrə/; Hebrew Teaching”), or the Pentateuch (/ˈpɛntəˌtuːk, -ˌtjuːk/), is the central reference of the religious Judaic tradition. It has a range of meanings. It can most specifically mean the first five books of the twenty-four books of the Tanakh, and it usually includes the rabbinic commen- Silver Torah Case, Ottoman Empire Museum of Jewish Art and taries. The term Torah means instruction and offers a way History of life for those who follow it; it can mean the continued narrative from Genesis to the end of the Tanakh, and it can even mean the totality of Jewish teaching, culture and generation to generation and are now embodied in the practice.[1] Common to all these meanings, Torah con- Talmud and Midrash.[2] sists of the foundational narrative of the Jews: their call According to rabbinic tradition, all of the teachings found into being by God, their trials and tribulations, and their in the Torah, both written and oral, were given by God covenant with their God, which involves following a way through Moses, a prophet, some of them at Mount Sinai of life embodied in a set of moral and religious obliga- and others at the Tabernacle, and all the teachings were tions and civil laws (halakha). written down by Moses, which resulted in the Torah we In rabbinic literature the word “Torah” denotes both the have today. According to a Midrash, the Torah was cre- Torah that is ated prior to the creation of the world, and was used as the“ ,תורה שבכתב) five books, Torah Shebichtav -blueprint for Creation.[3] The majority of Biblical schol תורה) written”), and an Oral Torah, Torah Shebe'al Peh Torah that is spoken”). -

Documentary Hypothesis

Documentary Hypothesis Notes from: 1. JOHN BARTON, "Source Criticism," The Anchor Bible Dictionary [http://www.ucalgary.ca/~eslinger/genrels/DocHypothesis.html] 2. http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/rs/2/Judaism/jepd.html 3. http:// www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Documentary_hypothesis.doc "SOURCE CRITICISM. [VI, 162] Formerly called “literary criticism” or “higher criticism,” source criticism is a method of biblical study, which analyzes texts that are not the work of a single author but result from the combination of originally separate documents. This method has been applied to texts of the Old Testament (especially but not exclusively the Pentateuch) and New Testament (especially but not exclusively the gospels). This entry surveys the application of this method to those texts. A. Definitions Modern literary conventions forbid plagiarism, and require authors to identify and acknowledge any material they have borrowed from another writer. But in ancient times it was common to “write” a book by transcribing existing material, adapting and adding to it from other documents as required, and not indicating which parts were original and which borrowed. The OT contains few books, which are the work of a single author throughout; for the most part its books are composite, and in some cases the source materials are drawn from original documents that may be spread over several centuries. Source criticism seeks to separate out these originally independent documents, and to assign them to relative (and, if possible, absolute) dates. Source criticism is to be distinguished from other critical methods. Where original documents prove not to have been free compositions, but to rest on older, oral tradition, FORM CRITICISM may then be used to penetrate behind the written text. -

JEDP Source Theory

JEDP Source Theory Literary analysis shows that the Pentateuch was not written by one person. Multiple strands of oral and written tradition were woven together to produce the Torah. The view that is persuasive to most of the critical scholars of the Pentateuch is called the Documentary Hypothesis, or the Graf-Wellhausen Hypothesis, after the names of the 19th-century scholars who put it in its classic form. It is also called the JEDP Source Theory, and since that is the most straight-forward name, that is the name we will be using in this class. Briefly stated, the JEDP Source Theory states that the Hebrew Bible (Christian Old testament) was written by a series of authors writing within 4 literary traditions. These traditions are known as J, E, D, and P. J (the Jahwist or Jerusalem source) uses YHWH as God's name. This source's interests indicate the writer most likely lived in the southern Kingdom of Judah in the time of the divided Kingdom. The J source is responsible for most of Genesis. E (the Elohist or Ephraimitic source) uses Elohim ("God") for the divine name until Exodus 3-6, where YHWH is revealed to Moses and to Israel. This source seems to have lived in the northern Kingdom of Israel during the divided Kingdom. E wrote Genesis 22 (the sacrifice of Isaac) story and other parts of Genesis, and much of Exodus and Numbers. J and E were joined fairly early, apparently after the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE. It is often difficult to separate J and E stories that have merged. -

From Mercy Seat to Judgment Seat: a Source-Critical Examination of Priestly Adjudication in the Pentateuch

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2020-08-04 From Mercy Seat to Judgment Seat: A Source-Critical Examination of Priestly Adjudication in the Pentateuch Tyler Harris Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Harris, Tyler, "From Mercy Seat to Judgment Seat: A Source-Critical Examination of Priestly Adjudication in the Pentateuch" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 164. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/164 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis FROM MERCY SEAT TO JUDGMENT SEAT: A SOURCE-CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF PRIESTLY ADJUDICATION IN THE PENTATEUCH by Tyler Joshua Harris Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors Ancient Near Eastern Studies Program Brigham Young University August 2020 Advisor: Matthew Grey Honors Coordinator: Eric Huntsman ABSTRACT FROM MERCY SEAT TO JUDGMENT SEAT: A SOURCE-CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF PRIESTLY ADJUDICATION IN THE PENTATEUCH Tyler Joshua Harris Ancient Near Eastern Studies Program Bachelor of Arts This thesis analyzes evidentiary passages in the Pentateuch through a source- critical lens to better understand the varied adjudicative ideologies they reflect and the role of priests in them. By selecting important pericopes for this analysis through keywords and narrative details, and then by categorizing them according to the pentateuchal source attributions as represented by Richard Elliott Friedman in his The Bible with Sources Revealed, I use a given source’s data to sketch the judicial outlook of said source, including if and to what degree priests operated as judges. -

Modern Commentaries on the Book of Exodus and Their Appropriateness in Africa

Modern Commentaries on the Book of Exodus And their Appropriateness in Africa Jonathan Tyosar Weor Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Theology at the University of Stellenbosch, South Africa. Supervisor: Prof H L Bosman April 2006 i DECLARATION I, the undersigned, hereby certify that the work contained in this thesis is my original work and has not previously, entirely or in part, been submitted at any University for a degree. Signature……………………………… Date…………………… ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my eldest brother, John Yandev Weor for his maximum support towards my studies in South Africa, my beloved wife, Atese Rebecca Seumbur Weor, and my loving daughter, Miss Favour Umburse Weor for their love, support, continued prayers, and patience during my long period of absence from them for my studies in South Africa. iii ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to explore the trends that are found in commentaries on the book of Exodus and their appropriateness in the African context. The study also seeks to move from a socio-political understanding of Exodus as liberation theology to the cultural understanding of Exodus as African theology. The following three trends are found in modern commentaries on Exodus as explored by this thesis: • Historical-critical approach – dealing with the world behind the text or author centred criticism. Commentaries found under this group include those of M Noth (1962), TE Fretheim (1990), N Sarna (1991), B S Childs (1977) and WHC Propp (1999). • Literary-critical approach – this deals with the text itself or it is text centred. -

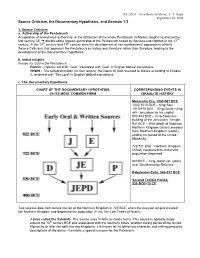

Source Criticism, the Documentary Hypothesis, and Genesis 1-3

RS 2DD3 – Five Books of Moses, A. Y. Reed September 20, 2004 Source Criticism, the Documentary Hypothesis, and Genesis 1-3 1. Source Criticism a. Authorship of the Pentateuch Acceptance of anonymous authorship à the attribution of the whole Pentateuch to Moses, beginning around the first century CE à doubts about Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch raised by Spinoza and Hobbes in the 17th century à the 18th century and 19th century sees the development of non-confessional approaches (chiefly Source Criticism) that approach the Pentateuch as history and literature rather than Scripture, leading to the development of the Documentary Hypothesis. b. Initial insights Names for God in the Pentateuch: Elohim – Hebrew word for “God,” translated with “God” in English biblical translations. YHWH – The tetragrammaton (lit. four letters), the Name of God revealed to Moses according to Exodus 3, rendered with “The Lord” in English biblical translations. c. The Documentary Hypothesis CHART OF THE DOCUMENTARY HYPOTHESIS, CORRESPONDING EVENTS IN IN ITS MOST COMMON FORM ISRAELITE HISTORY Monarchic Era, 1000-587 BCE 1030-1010 BCE – King Saul 1010-970 BCE – King David, ruling with Jerusalem as his capital 970-931 BCE – King Solomon; building of the Jerusalem Temple 931 BCE – With death of Solomon, Northern Kingdom (Israel) secedes from Southern Kingdom (Judah), ending the period of the United Monarchy 722/721 BCE - Northern Kingdom (Israel) conquered by Assyrians, population dispersed 620 BCE – King Josiah (of Judah) and "Deuteronomic Reforms" Babylonian Exile, 586-537 BCE Second Temple Period, 539 BCE–70 CE Two sources date from before the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BCE, when the Assyrian empire invaded the Northern Kingdom and dispersed the population (= the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel): J (also called the Yahwist): This source uses YHWH as God's name. -

Re-Examined Under the Documentary Hypothesis

Antwi, “Joseph-narrative and Documentary Hypothesis,” OTE 29/2 (2016): 259-276 259 Sources, Formation and Socio-Historical Context of the Joseph Narrative: Re-Examined under the Documentary Hypothesis EMMANUEL KOJO ENNIN ANTWI (KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY, KUMASI, GHANA) ABSTRACT The historical-critical method has given birth to many approaches to the study of the Bible. As a consequence, many scholars have come up with solutions to some of the exegetical problems in the Judeo-Chris- tian scriptures. One of the most popular proposed solutions to the problems in the Pentateuch is the Documentary Hypothesis. With time, the findings of the hypothesis have been challenged in reference to some texts in the Pentateuch. This paper seeks to re-examine the sources, formation and the socio-historical context of the Joseph nar- rative under the Documentary Hypothesis. It evaluates the Joseph nar- rative under the hypothesis in the light of its critique by later scholars. The essay argues that the narrative is composed of already-existing materials from the Ancient Near East, Egypt and the traditions from Israel to reflect some aspects of the history of Israel in retrospect. Weighing the sources according to the hypothesis as against the views of its critics, who accept the narrative as a unity, one discovers that some traces of source criticism are apparent in the views of the critics of the Documentary Hypothesis. They were solving similar problems within the narrative but from different perspectives. KEYWORDS: Joseph narrative; Documentary Hypothesis; Source criticism; Yahwist source; Elohist source; Priestly source. A INTRODUCTION Chapters 37 to 50 of Genesis constitute the Joseph narrative. -

THE ANOINTING of AARON: a STUDY of LEVITICUS 8:12 in ITS OT and ANE Contextl

Andrews University Seminary Studies, 38.2 (Autumn 2000) 231-243. Copyright © 2000 by Andrews University Press. Cited with permission. THE ANOINTING OF AARON: A STUDY OF LEVITICUS 8:12 IN ITS OT AND ANE CONTEXTl GERALD KLINGBEIL Peruvian Union University Lima, Peru Introduction Lev 8:122 forms an integral part of the ritual of ordination of Aaron and his sons and the consecration of the Tabernacle and is shaped after the commandment section found in Exod 29, dealing with the technical and procedural aspects of the ordination and consecration ritual.3 This study first 1The present article is a revision of one originally published as 'La uncion de Aaron. Un estudio de Lev 8:12 en su centexto veterotestamentario y antiguo cercano-oriental,' Theologika 11/1 (1996): 64-83. (Theologika is a biennial theological journal of Universidad Peruana Union, Lima, Peru.) The study is partly based on research undertaken for the author's D .Litt. thesis at the University of Stellenbosch. See G. A. Klingbeil, "Ordination and Ritual: On the Symbolism of Time, Space, and Actions in Leviticus 8," (D. Litt. diss. University of StelIenbosch, 1995). A revised version of the dissertation has been published in 1998 by Edwin Mellen Press under the title A Comparative Study of the Ritual of Ordination as Found in Leviticus 8 and Emar 369. The financial assistance of the South African Center for Science Development toward this research is hereby acknowledged. Furthermore, the author would like to thank the University of Stellenbosch for awarding him the Stellenbosch 2000 bursary, which constituted a substantial help in the financing of the doctoral studies. -

Fundamental Questions in the Study of Tanakh by Rav Amnon Bazak Duplication and Contradiction (Part 1) A. Background The

Fundamental Questions in the Study of Tanakh By Rav Amnon Bazak Duplication and Contradiction (Part 1) A. Background The awareness that the Torah contains many instances of duplication, as well as contradictions between different sources, has always existed. Chazal address these phenomena in many places, and note them using expressions such as, "Two biblical verses contradict one another"; "one verse says… while another verse says…." The commentators broaden the discussion even further, and propose different explanations for the phenomena of repetition and contradiction in Tanakh, both in relation to contradictions between different textual units, and in relation to contradictions that occur within one single unit.[1] To illustrate the phenomenon, let us list some of the better-known contradictions. 1. The most famous would seem to be the two descriptions of the Creation, as set forth in chapter 1 and chapter 2 of Bereishit. Chapter 1 suggests that first the plants were created (verses 11-12), followed by animals (verses 20-25), and finally man – male and female together (verse 27). In chapter 2, by contrast, man is created first (verse 7), followed by vegetation (verses 8-9), with the text emphasizing that there was no point in creating plants prior to the appearance of man, and animals are created only in order to serve as a "helpmate" to man (verses 18-20). Woman, too, is created at a later stage, from one of Man's ribs (verses 21-23). 2. Duplications and contradictions of this sort continue throughout the narrative in Bereishit. The story of the Flood, for example, is built on a systematic duality: twice we are told that God sees the evil of man and decides to destroy mankind from upon the earth (verses 5-8; 9-13); twice God commands Noach to bring the animals into the Ark, and twice we are told that Noach does everything as God commands him (6:14-22; 7:1-5).