Jerusalem: Boundaries, Spaces, and Heterotopias of Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank

This Road Leads to Area “A” Under the Palestinian Authority, Beware of Entering: Palestinian Ghetto Policies in the West Bank Razi Nabulsi* “This road leads to Area “A” under the Palestinian Authority. The Entrance for Israeli Citizens is Forbidden, Dangerous to Your Lives, And Is Against The Israeli Law.” Anyone entering Ramallah through any of the Israeli military checkpoints that surround it, and surround its environs too, may note the abovementioned sentence written in white on a blatantly red sign, clearly written in three languages: Arabic, Hebrew, and English. The sign practically expires at Attara checkpoint, right after Bir Zeit city; you notice it as you leave but it only speaks to those entering the West Bank through the checkpoint. On the way from “Qalandia” checkpoint and until “Attara” checkpoint, the traveller goes through Qalandia Camp first; Kafr ‘Aqab second; Al-Amari Camp third; Ramallah and Al-Bireh fourth; Sarda fifth; and Birzeit sixth, all the way ending with “Attara” checkpoint, where the red sign is located. Practically, these are not Area “A” borders, but also not even the borders of the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate, neither are they the West Bank borders. This area designated by the abovementioned sign does not fall under any of the agreed-upon definitions, neither legally nor politically, in Palestine. This area is an outsider to legal definitions; it is an outsider that contains everything. It contains areas, such as Kafr ‘Aqab and Qalandia Camp that belong to the Jerusalem municipality, which complies -

Jerusalem: City of Dreams, City of Sorrows

1 JERUSALEM: CITY OF DREAMS, CITY OF SORROWS More than ever before, urban historians tell us that global cities tend to look very much alike. For U.S. students. the“ look alike” perspective makes it more difficult to empathize with and to understand cultures and societies other than their own. The admittedly superficial similarities of global cities with U.S. ones leads to misunderstandings and confusion. The multiplicity of cybercafés, high-rise buildings, bars and discothèques, international hotels, restaurants, and boutique retailers in shopping malls and multiplex cinemas gives these global cities the appearances of familiarity. The ubiquity of schools, university campuses, signs, streetlights, and urban transportation systems can only add to an outsider’s “cultural and social blindness.” Prevailing U.S. learning goals that underscore American values of individualism, self-confidence, and material comfort are, more often than not, obstacles for any quick study or understanding of world cultures and societies by visiting U.S. student and faculty.1 Therefore, international educators need to look for and find ways in which their students are able to look beyond the veneer of the modern global city through careful program planning and learning strategies that seek to affect the students in their “reading and learning” about these fertile centers of liberal learning. As the students become acquainted with the streets, neighborhoods, and urban centers of their global city, their understanding of its ways and habits is embellished and enriched by the walls, neighborhoods, institutions, and archaeological sites that might otherwise cause them their “cultural and social blindness.” Jerusalem is more than an intriguing global historical city. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

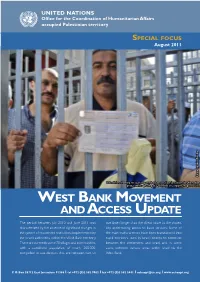

West Bank Movement Andaccess Update

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory SPECIAL FOCUS August 2011 Photo by John Torday John Photo by Palestinian showing his special permit to access East Jerusalem for Ramadan prayer, while queuing at Qalandiya checkpoint, August 2010. WEST BANK MOVEMENT AND ACCESS UPDATE The period between July 2010 and June 2011 was five times longer than the direct route to the closest characterized by the absence of significant changes in city, undermining access to basic services. Some of the system of movement restrictions implemented by the main traffic arteries have been transformed into the Israeli authorities within the West Bank territory. rapid ‘corridors’ used by Israeli citizens to commute There are currently some 70 villages and communities, between the settlements and Israel, and, in some with a combined population of nearly 200,000, cases, between various areas within Israel via the compelled to use detours that are between two to West Bank. P. O. Box 38712 East Jerusalem 91386 l tel +972 (0)2 582 9962 l fax +972 (0)2 582 5841 l [email protected] l www.ochaopt.org AUGUST 2011 1 UN OCHA oPt EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The period between July 2010 and June 2011 Jerusalem. Those who obtained an entry permit, was characterized by the absence of significant were limited to using four of the 16 checkpoints along changes in the system of movement restrictions the Barrier. Overcrowding, along with the multiple implemented by the Israeli authorities within the layers of checks and security procedures at these West Bank territory to address security concerns. -

"The Jewish National and University Library Has Gathered Tens of Thousands of Abandoned Books During the War

"The Jewish National and University Library has gathered tens of thousands of abandoned books during the war. We thank the people of the army for the love and understanding they have shown towards this undertaking" This essay was originally published (in Hebrew) in Mitaam: a Review for radical thought 8 (December 2006), pp. 12-22. This essay was written in the framework of my doctoral dissertation entitled: "The Jewish National and University Library 1945- 1955: The Appropriation of Palestinian Books, the Confiscation of Cultural Property from Jewish Immigrants from Arab Countries and the Collection of Books Left Behind by Holocaust Victims. Gish Amit Translated by Rebecca Gillis Goodbye, my books! Farewell to the house of wisdom, the temple of philosophy, the scientific institute, the literary academy! How much midnight oil did I burn with you, reading and writing, in the silence of the night while the people slept … farewell, my books! … I do not know what became of you after we left: were you looted? Burned? Were you transferred, with due respect, to a public or private library? Did you find your way to the grocer, your pages wrapping onions?1 When Khalil al-Sakakini, a renowned educator and Christian Arab author, fled his home in the Jerusalem neighborhood of Katamon, on 30th April 1948, one day after the occupation of the neighborhood by the Hagana forces, he left behind not only his house and furniture, his huge piano, electric refrigerator, liquor cupboard and narghila, but also his books. Like others, he believed he would soon return home. Nineteen years later, in the summer of 1967, Sakakini's daughter visited The Jewish National and University Library with her sister, and discovered there her father's books with the notes he used to inscribe on them. -

Sukkot Real Estate Magazine

SUKKOT 2020 REAL ESTATE Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Rotshtein The next generation of residential complexes HaHotrim - Tirat Carmel in Israel! In a perfect location between the green Carmel and the Mediterranean Sea, on the lands of Kibbutz HaHotrim, adjacent to Haifa, the new and advanced residential project Rotshtein Valley will be built. An 8-story boutique building complex that’s adapted to the modern lifestyle thanks to a high premium standard, a smart home system in every apartment and more! 4, 5-room apartments, garden Starting from NIS apartments, and penthouses Extension 3 GREEN CONSTRUCTION *Rendition for illustration only Living the high Life LETTER FROM THE EDITOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Dear Readers, With toWers Welcome to the Sukkot edition of The Jerusalem THE ECONOMY: A CHALLENGING CONUNDRUM ....................08 Post’s Real Estate/Economic Post magazine. Juan de la Roca This edition is being published under the shadow of the coronavirus pandemic. Although not all the articles herein are related to the virus, it is a reality BUILDING A STRONGER FUTURE ............................................... 12 that cannot be ignored. -

The Upper Kidron Valley

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi Jerusalem 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies – Study No. 398 The Upper Kidron Valley Conservation and Development in the Visual Basin of the Old City of Jerusalem Editor: Israel Kimhi This publication was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, San Francisco. 7KHFRQWHQWRIWKLVGRFXPHQWUHÀHFWVWKHDXWKRUV¶RSLQLRQRQO\ Photographs: Maya Choshen, Israel Kimhi, and Flash 90 Linguistic editing (Hebrew): Shlomo Arad Production and printing: Hamutal Appel Pagination and design: Esti Boehm Translation: Sagir International Translations Ltd. © 2010, The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 92186 http://www.jiis.org E-mail: [email protected] Research Team Israel Kimhi – head of the team and editor of the report Eran Avni – infrastructures, public participation, tourism sites Amir Eidelman – geology Yair Assaf-Shapira – research, mapping, and geographical information systems Malka Greenberg-Raanan – physical planning, development of construction Maya Choshen – population and society Mike Turner – physical planning, development of construction, visual analysis, future development trends Muhamad Nakhal ±UHVLGHQWSDUWLFLSDWLRQKLVWRU\SUR¿OHRIWKH$UDEQHLJKERU- hoods Michal Korach – population and society Israel Kimhi – recommendations for future development, land uses, transport, planning Amnon Ramon – history, religions, sites for conservation Acknowledgments The research team thanks the residents of the Upper Kidron Valley and the Visual Basin of the Old City, and their representatives, for cooperating with the researchers during the course of the study and for their willingness to meet frequently with the team. -

Michael Alper, St. Louis, MO Rabbi Michael Alper Is Proud to Share the Rabbinic Leadership of Congregation Temple Israel

Michael Alper, St. Louis, MO Rabbi Michael Alper is proud to share the rabbinic leadership of Congregation Temple Israel. Born in Los Angeles, California, Rabbi Alper lived in many parts of the country before settling in St. Louis. He holds a Bachelor's Degree in History from Boston University, and was ordained at the Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, in New York City. An enthusiastic teacher, Rabbi Alper taught public school in the South Bronx and served as the Director of the Miller High School Honors Program at Hebrew Union College in New York. Rabbi Alper served as the Director of Education of Central Reform Congregation for two years before joining the Temple Israel clergy. At Temple Israel, one of his most important roles is working individually with the B'nai Mitzvah students and their families to create meaningful Jewish experiences that will shape their lives. A gifted artist and musician, Rabbi Alper is particularly interested in working with youth and music, encouraging young people to access their Judaism in unique and fulfilling ways. Rich Bardusch, Needham, MA The Reverend Dr. Rich Bardusch is rector of the Episcopal Church of St. Thomas in Taunton, Massachusetts. He is a graduate of Duke Divinity School and has a Doctor of Ministry in Congregational Development from Drew University. He is a bit of a Thomist and enjoys traveling. His spiritual discipline includes Centering Prayer and simple living. He is a gardener, sci-fi fan, and patio reader extraordinaire. His interests include interfaith dialogue, Christian liturgy, and plants. He loves dogs and being at the center of a vibrant religious community, which is seeking to be faithful followers of Jesus. -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010

Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Founded by the Charles H. Revson Foundation Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009 / 2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach 2010 Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Publication No. 402 Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2009/2010 Maya Choshen, Michal Korach This publication was published with the assistance of the Charles H. Revson Foundation, New York The authors alone are responsible for the contents of the publication Translation from Hebrew: Sagir International Translation, Ltd. © 2010, Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 92186 Jerusalem [email protected] http://www.jiis.org Table of Contents About the Authors ............................................................................................. 7 Preface ................................................................................................................ 8 Area .................................................................................................................... 9 Population ......................................................................................................... 9 Population size ........................................................................................... 9 Geographical distribution of the population .............................................11 Population growth .................................................................................... 12 Sources of population growth .................................................................. 12 Birth -

The Reality of Palestinian Refugee Camps in Light of COVID-19”

A Policy Paper entitled: “The Reality of Palestinian Refugee Camps in light of COVID-19” Written by: Raed Mohammad Al-Dib’i Introduction: According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, there are 58 official Palestinian refugee camps affiliated to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), of which 10 are in Jordan, 9 in Syria, 12 in Lebanon, 19 in the West Bank and 8 in the Gaza Strip. However, there are a number of camps that are not recognized by the UNRWA.1 17% of the 6.2 million Palestinian refugees registered with UNRWA reside in the West Bank, compared to 25% in the Gaza Strip; while the rest is distributed among the diaspora, including the Arab countries.2 The Coronavirus pandemic poses a great challenge in addition to those that the Palestinian refugees already encounter in refugee camps, compared to other areas for a number of reasons, including the low level of health services provided by UNRWA - originally modest - especially after the latter's decision to reduce its services to refugees, the high population density in the camps, which makes the implementation of public safety measures, social distancing and home quarantine to those who have COVID-19 and who they were in contact with a complex issue. Another reason is the high rate of unemployment in the Palestinian camps, which amounts to 39%, compared to 22% for non-refugees3, thus, constituting an additional challenge in light of the pandemic. The Palestinian National Authority (PNA) adopts the policy of partial or complete closure to combat the COVID-19 outbreak in light of the inability to provide the requirements for a decent life to all of its citizens for numerous reasons. -

Ex-Communicated:限 Historicalreflectionsonenclosure

Photo Essays Ex-Communicated: HistoricalReflectionsonEnclosure LandscapesinPalestine Gary Fields From a small hilltop on the Beit Hanina side of the Qalandia checkpoint near the Palestinian town of Ramallah, a landscape of imposing built forms and regi- mented human bodies beckons to a theme now central to historical studies, the nature of modern power and its relationship to territorial space. To the north of the checkpoint, a concrete wall emerges from the western horizon and sweeps forcefully across the land, partially concealing the town of Qalandia behind its grayish, fore- boding exterior (fig. 1). Along the once vibrant Jerusalem- Ramallah road where the Palestinian towns of Ar Ram, Beit Hanina, and Qalandia formerly converged, a sec- ond wall runs perpendicular to and eventually connects with the first, disconnecting these towns from one another while emitting an unmistakable aura of emptiness and immobility. In the space where these towns were once joined together stand several prison- like guard towers that now surround the checkpoint terminal. Here, under the gaze of mostly young military overseers, Palestinians are processed as they try to move from one geographical location to another. While this landscape is dramatic in the way it reconfigures land and controls the movements of people, it is not unique. Many other venues distributed throughout the West Bank host the same drama of power and space in which military authorities and Palestinian civilians engage in similarly scripted rituals of domination and submission, with the same stage set of coldly formidable architectural forms invariably hovering over the actors below. Radical History Review Issue 108 (Fall 2010) d o i 10.1215/01636545-2010-008 © 2010 by MARHO: The Radical Historians’ Organization, Inc.