I. MF Global A. Introduction Following the Financial Crisis of 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCH 28, 2012 Chairman Neugebauer, Ranking Member

STATEMENT OF DIANE GENOVA BEFORE THE UNITED STATES HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES OVERSIGHT AND INVESTIGATIONS SUBCOMMITTEE MARCH 28, 2012 Chairman Neugebauer, Ranking Member Capuano, and Members of the Subcommittee, good afternoon. My name is Diane Genova. I am the Deputy General Counsel for the investment bank of JPMorgan Chase & Co. I am pleased to appear this afternoon on behalf of J.P. Morgan in order to describe for you certain of the interactions J.P. Morgan had with MF Global before MF Global filed for bankruptcy protection on October 31, 2011. I appreciate the opportunity to appear before the Subcommittee. As I will describe in more detail, J.P. Morgan professionals worked very hard throughout the week of October 24 to accomplish two main goals: first, we took what we believed were appropriate and prudent steps, as part of maintaining safe and sound banking operations, to ensure that we did not wind up in a position where we had extended credit to MF Global without proper collateral and security protections; and, second, our professionals simultaneously worked very hard that week to provide first-rate operational clearing and settlement support and services to MF Global. With those goals in mind, J.P. Morgan also sought to collect as much information as we could from MF Global about its liquidity situation under what were very difficult, rapidly changing circumstances. We were always mindful that despite our best efforts, there was a lot going on inside MF Global during that week that we were not seeing and could not see. -

Wall St. and the Law: Customer Fund Protections After the Collapse of MF Global and Peregrine -- What Regulatory Changes Are Taking Place

E TUT WALL ST. AND THE LAW: I CUSTOMER FUND PROTECTIONS ST AFTER THE COLLApsE OF MF N GLOBAL AND PEREGRINE – WHAT REGULATORY CHANGES ARE TAKING PLACE Prepared in connection with a Continuing Legal Education course presented at New York County Lawyers’ Association, 14 Vesey Street, New York, NY presented on Tuesday, June 18, 2013. P ROGR A M C O - S P O N SOR : New York Law (NYLS) School Financial Services Law Institute P ROGR A M M OD E R A TOR : Prof. Ronald H. Filler, NYLS Professor of Law and, Director, Financial Services Law Institute, NYLS P ROGR A M F ac U L T Y : Steven Lofchie, Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft; Robert L. Sichel, Pacific Global Advisors; Gary DeWaal , Gary DeWaal & Associates (former Group General Counsel of Newedge) NYCLA-CLE I 2 TRANSITIONAL & NON-TRANSITIONAL MCLE CREDITS: This course has been approved in accordance with the requirements of the New York State Continuing Legal Education Board for a maximum of 2 Transitional & Non-Transitional credit hours: .5 Ethics; 1.5 PP This program has been approved by the Board of Continuing Legal Education of the Supreme Court of New Jersey for 2 hours of total CLE credit. Of these, 0 qualify as hours of credit for Ethics/Professionalism, and 0 qualify as hours of credit toward certification in civil trial law, criminal trial law, workers compensation law and/or matrimonial law. Information Regarding CLE Credits and Certification Wall Street and the Law June 18, 2013; 6:00 PM to 8:00 PM The New York State CLE Board Regulations require all accredited CLE providers to provide documentation that CLE course attendees are, in fact, present during the course. -

The Collapse of MF Global: Summary & Analysis

The Collapse of MF Global: Summary & Analysis By: Cause of Action Introduction Less than two years after Jon Corzine became CEO of MF Global Holdings, Ltd., the international commodities broker filed a voluntary petition for bankruptcy under Chapter 11 on October 31, 2011 – fittingly enough on Halloween, the most frightening day of the year, as MF Global’s brokerage customers would soon discover. The company’s failure has since been blamed on a risky trading strategy that Corzine introduced to increase revenues in the face of MF Global’s declining core business. Corzine effectively engineered a more than $6 billion bet on the sovereign debt of Ireland, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Belgium through the use of a financial transaction commonly referred to as a “Repo to Maturity” (RTM). Although Corzine was prescient in betting that European sovereign debt would not default, margin calls by MF Global’s counterparties ultimately overwhelmed the company and triggered a classic liquidity crisis. By the time the tailspin had reached its natural conclusion, $1.6 billion of customer funds were missing due to sloppy bookkeeping and mismanagement. As a financial services holding company, MF Global Holdings has a number of subsidiaries throughout the world. MF Global, Inc. (MFGI) was the company’s U.S.-based futures commission merchant (FCM) and registered broker-dealer, subject to regulation by both the CFTC and SEC. MFGI was also a designated primary dealer in U.S. Treasury securities. MF Global’s UK-based subsidiary (MFGUK) was instrumental in the vast majority of the trades the firm embarked. A traditional bankruptcy trustee has been appointed to oversee the liquidation of MF Global Holdings, the parent company, while the Securities Investor Protection Corporation has appointed its own trustee to liquidate MFGI, the FCM/broker-dealer. -

1 UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS 2 3 for the SECOND CIRCUIT 4 5 August Term, 2009 6 7 8 (Argued: July 15, 2010 Decided: September 14, 2010) 9 10 Docket No

09-3919-cv Iowa Pub. Employees’ Ret. Sys. v. MF Global, Ltd. 1 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS 2 3 FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT 4 5 August Term, 2009 6 7 8 (Argued: July 15, 2010 Decided: September 14, 2010) 9 10 Docket No. 09-3919-cv 11 12 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -x 13 14 IOWA PUBLIC EMPLOYEES’ RETIREMENT SYSTEM, POLICEMEN’S 15 ANNUITY & BENEFIT FUND OF CHICAGO, CENTRAL STATES, SOUTHEAST 16 AND SOUTHWEST AREAS PENSION FUND, STATE-BOSTON RETIREMENT 17 SYSTEM, MF GLOBAL INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS GROUP, 18 19 Plaintiffs-Appellants, 20 21 MICHAEL RUBIN, individually and on behalf of all others 22 similarly situated, 23 24 Plaintiff, 25 26 NANETTE KATZ, FRANK MATASSA, SUNSHINE WIRE AND CABLE DEFINED 27 BENEFIT PLAN TRUST, individually and on behalf of all others 28 similarly situated, MICHAEL J. RUDNICK, individually and on 29 behalf of all others similarly situated, 30 31 Consolidated-Plaintiffs, 32 33 - v.- 34 35 MF GLOBAL, LTD., MAN GROUP, PLC, KEVIN R. DAVIS, AMY S. 36 BUTTE, ALISON J. CARNWATH, CHRISTOPHER J. SMITH, CHRISTOPHER 37 BATES, HENRI J. STEENKAMP, EDWARD L. GOLDBERG, DEUTSCHE BANK 38 SECURITIES, INC., ABN AMRO ROTHSCHILD LLC, BANC OF AMERICA 39 SECURITIES, LLC, BMO CAPITAL MARKETS CORP., HSBC SECURITIES 40 (USA) INC., KEEFE, BRUYETTE & WOODS, INC., SANDLER O’NEILL & 41 PARTNERS, L.P., WACHOVIA CAPITAL MARKETS LLC, CL KING & 42 ASSOCIATES, INC., DOWLING & PARTNERS SECURITIES, LLC, 1 E*TRADE SECURITIES LLC, FORTIS SECURITIES LLC, GUZMAN & CO., 2 ING FINANCIAL MARKETS, LLC, JEFFRIES & CO., INC., LAZARD 3 CAPITAL MARKETS LLC, M.R. BEAL & CO., MIZUHO SECURITIES USA, 4 INC., MURIEL SIEBERT & CO., INC., OPPENHEIMER & CO., INC., 5 PIPER, JAFFRAY & CO., RAYMOND JAMES & ASSOCIATES, INC., RBC 6 MARKETS CORP., ROBERT W. -

Could Problems at MF Global Have Been Anticipated?

J.P. Morgan Center for Commodities at the University of Colorado Denver Business School Could Problems at MF Global Have Been Anticipated? Hilary Till Contributing Editor, Global Commodities Applied Research Digest; and Solich Scholar, J.P. Morgan Center for Commodities, University of Colorado Denver Business School As summarized in Heckinger (2016), “on October 31, 2011, the broker–dealer (B/D) and futures commission merchant (FCM) firm of the MF Global Group (i.e., MFG, the group, and all its parts) collapsed, causing substantial financial distress to its customers, many of whom were small investors or hedgers such as farmers, ranchers or commodity merchants such as grain elevator operators. About $1.6 billion of customers’ funds were not immediately available for liquidation proceedings due to the apparent misallocation of customer funds, which were not segregated from firm accounts, and the use of the funds to fund proprietary trading, which resulted in the encumbrance of such funds.” Four years later, “recovery and distribution actions of the respective bankruptcy trustees and administrators appointed to liquidate the firm made all customers whole, depending on the jurisdiction and particular MFG business entity. Other creditors such as vendors or suppliers of services to MFG received around 95 percent of the value of their claims,” wrote Heckinger (2016). But back in the fall of 2011, futures market participants were caught off-guard when MF Global filed for bankruptcy. Essentially, this episode educated industry participants that customer protections in the U.S. commodity futures markets had been more ambiguous than expected. That said, there are a number of reforms that have been undertaken to help prevent future MF Globals. -

MF GLOBAL HOLDINGS LTD., ET AL. Post-Effective Date Quarterly Operating Report for the Period Ending September 30, 2018

MF GLOBAL HOLDINGS LTD., ET AL. Post-Effective Date Quarterly Operating Report For the period ending September 30, 2018 MF GLOBAL HOLDINGS LTD., ET AL. Post-Effective Date Quarterly Operating Report For the period ending September 30, 2018 BACKGROUND This post-Effective Date quarterly operating report (“QOR”) of MF Global Holdings Ltd. (“Holdings Ltd.”) and its affiliated debtors, MF Global Finance USA Inc. (“Finance USA”), MF Global Capital LLC (“Capital”), MF Global FX Clear LLC (“FX Clear”), MF Global Market Services LLC (“Market Services”), and MF Global Holdings USA Inc. (“Holdings USA”) (collectively, the “Debtors”1) covers a specific time period and has been prepared solely for the purpose of complying with the reporting requirements of the Second Amended and Restated Joint Plan of Liquidation Pursuant to Chapter 11 of the Bankruptcy Code for MF Global Holdings Ltd., MF Global Finance USA Inc., MF Global Capital LLC, MF Global FX Clear LLC, MF Global Market Services LLC, and MF Global Holdings USA Inc. (Docket No. 1382) (the “Second Amended Plan”). The financial information contained in this QOR is preliminary and unaudited, and as such may be subject to revision. The information in this QOR should not be viewed as indicative of future results. The Second Amended Plan is a joint plan for six separate Debtors. The Debtors are not consolidated for financial reporting and should be viewed as standalone entities. The total columns in each of the tables of the QOR are for illustrative purposes only. The Debtors filed voluntary petitions for relief under chapter 11 of title 11 of the United States Code (the “Bankruptcy Code”) in the Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of New York (the “Bankruptcy Court”) as follows: (i) Holdings Ltd. -

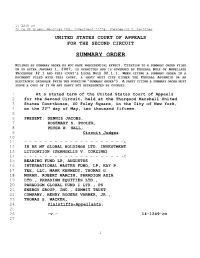

Summary Order

14-1249-cv In re MF Global Holdings Ltd. Investment Litig. (Deangelis v. Corzine) UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT SUMMARY ORDER RULINGS BY SUMMARY ORDER DO NOT HAVE PRECEDENTIAL EFFECT. CITATION TO A SUMMARY ORDER FILED ON OR AFTER JANUARY 1, 2007, IS PERMITTED AND IS GOVERNED BY FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 32.1 AND THIS COURT’S LOCAL RULE 32.1.1. WHEN CITING A SUMMARY ORDER IN A DOCUMENT FILED WITH THIS COURT, A PARTY MUST CITE EITHER THE FEDERAL APPENDIX OR AN ELECTRONIC DATABASE (WITH THE NOTATION “SUMMARY ORDER”). A PARTY CITING A SUMMARY ORDER MUST SERVE A COPY OF IT ON ANY PARTY NOT REPRESENTED BY COUNSEL. 1 At a stated term of the United States Court of Appeals 2 for the Second Circuit, held at the Thurgood Marshall United 3 States Courthouse, 40 Foley Square, in the City of New York, 4 on the 22nd day of May, two thousand fifteen. 5 6 PRESENT: DENNIS JACOBS, 7 ROSEMARY S. POOLER, 8 PETER W. HALL, 9 Circuit Judges. 10 11 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X 12 IN RE MF GLOBAL HOLDINGS LTD. INVESTMENT 13 LITIGATION (DEANGELIS V. CORZINE) 14 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X 15 BEARING FUND LP, AUGUSTUS 16 INTERNATIONAL MASTER FUND, LP, KAY P. 17 TEE, LLC, MARK KENNEDY, THOMAS G. 18 MORAN, ROBERT MARCIN, PARADIGM ASIA 19 LTD., PARADIGM EQUITIES LTD., 20 PARADIGM GLOBAL FUND I LTD., PS 21 ENERGY GROUP, INC., SUMMIT TRUST 22 COMPANY, HENRY ROGERS VARNER, JR., 23 THOMAS S. WACKER, 24 Plaintiffs-Appellants, 25 26 -v.- 14-1249-cv 27 1 1 PRICEWATERHOUSECOOPERS LLP, 2 Defendant-Appellee.* 3 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -X 4 5 FOR APPELLANTS: ANDREW J. -

MF Global Collapse FIA International Futures Industry Conference Things Happen March 13-16, 2012 at Boca Boca Raton Resort & Club

New Era for Wheat Futures | Kospi Explosion on Eurex | Dodd-Frank Update JANUARY 2012 | V22.N1 Washington Examines MF Global Collapse FIA International Futures Industry Conference Things Happen March 13-16, 2012 at Boca Boca Raton Resort & Club 1976 The first FIA International Futures Industry Conference is held in 1978 The first Commodity Futures Trading Commission Chairman Innisbrook. The conference moves to the Boca Raton Hotel and Club in 1979 William T. Bagley delivers his first major address to the futures industry. where it remains for the next 32 years with the exception of one year in Miami (1980) when the hotel is under renovation. 1985 Robert Rubin, Goldman Sachs, predicts that the futures industry could suffer “if stock index futures trading at some point really upends trading on the New York Stock Exchange … it will resurrect the 1983 John Damgard’s first Boca as president latent view of futures activity as socially useless speculation and that of the Futures Industry Association. will cause us a lot of trouble in the regulatory arena.” 1989 Chicago Board of Trade unveils “Aurora”, an electronic trading system that 1993 CME Chairman Jack Sandner puts forth a plan to tries to simulate the pit on a trading screen; create a financial super agency to replace the Commodity traders will use a pointing device known as Futures Trading Commission and the Securities and a “mouse”. Exchange Commission. 1995 Two weeks after the demise of Barings Bank, FIA assembles a panel 1996 International futures regulators from 14 jurisdictions sign a on the crisis and establishes FIA Global Task Force on Financial Integrity to Declaration on Cooperation and Supervision of International Futures make recommendations that would enhance the protection of the assets of Exchanges and Clearing Organizations—49 international foreign market participants. -

Trading with Other People's Money the Collapse of The

Copyright December 7th, 2011 Trading wiTh oTher people’s money The Collapse of the - WORLD Financial System Why MF Global is worse than Europe 1 Please register for Special Updates ArmstrongEconomics.COM Copyright Martin A. Armstrong All Rights Reserved This Report may be forwarded as you like without charge to individuals or governments around the world. It is provided as a Public Service at this time without cost because of the critical facts that we now faced economically. The contents and· designs of the systems are in fact copyrighted. Disclaimer: Futures, Options, and Currency trading all have large potential rewards, but also large potential risk. You must be aware of the risks and be willing to accept them in order to invest in these complex markets. Don’t trade with money you can’t afford to lose and NEVER trade anything blindly. You must strive to understand the markets and to act upon your conviction when well researched. This is neither a solicitation nor an offer to Buy/Sell futures, options, or currencies. No representation is being made that any account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses. Indeed, events can materialize rapidly and thus past performance of any trading system or methodology is not necessarily indicative of future results particularly when you understand we are going through an economic evolution process and that includes the rise and fall of various governments globally on an economic basis. CFTC Rule 4.41 – Any simulated or hypothetical performance results have certain inherent limitations. While prices may appear within a given trading range, there is no guarantee that there will be enough liquidity (volume) to ensure that such trades could be actually executed. -

Complaint: MF Global Inc., Et Al

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORI( U.S. COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION, Plaintiff, v. MF GLOBAL INC., MF GLOBAL HOLDINGS LTD., JURYT JON S. CORZINE, and EDITH O'BRIEN, ECFCase Defendants. COMPLAINT FOR INJUNCTIVE AND OTHER EQUITABLE RELIEF AND FOR CIVIL MONETARY PENALTIES UNDER THE COMMODITY EXCHANGE ACT The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission ("Commission" or "CFTC"), by and through its attorneys, alleges as follows: I. SUMMARY 1. It has long been a cornerstone of customer protection laws that a commodity futures broker, known as a futures commission merchant ("FCM"), must at all times segregate customer funds intended for futures trading on U.S. exchanges ("customer segregated funds") and may never use these customer funds for the FCM' s own purposes. When an FCM knows or should know that accounts holding customer segregated funds ("customer segregated accounts") do not hold sufficient funds to meet the FCM's financial obligations to all customers, the FCM, through its responsible personnel, must immediately notify the CFTC and the applicable designated self-regulatory organization ("DSRO"). To safeguard customer funds further, CFTC regulations limit an FCM's ability to invest customer funds to ce1iain authorized investments. In this case, MF Global Inc. ("MF Global"), an FCM with deficient systems and controls, on the brink of failure and in desperate need of cash to survive, invaded its customer funds and violated these fundamental customer protections on a scale never previously seen in the U.S. futures markets, harming thousands of people. As alleged below, Jon Corzine, the Chief Executive Officer ("CEO"), is legally responsible for MF Global's misuse of customer money. -

MF GLOBAL INC., Debtor. Case No. 11-2790

UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT FOR PUBLICATION SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re: Case No. 11-2790 (MG) SIPA MF GLOBAL INC., Debtor. HSBC BANK USA, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION, Interpleader Plaintiff, v. Adv. Proc. No. 11-02924 (MG) JASON FANE and JAMES W. GIDDENS, in his capacity as Trustee for MF Global Inc., Interpleader Defendants. MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER APPROVING SETTLEMENT AGREEMENT A P P E A R A N C E S: HUGHES HUBBARD & REED LLP Counsel for James W. Giddens, Trustee for the SIPA Liquidation of MF Global Inc. One Battery Park Plaza New York, New York 10004 By: James B. Kobak, Jr., Esq. Christopher K. Kiplok, Esq. Jeffrey S. Margolin, Esq. Dina R. Hoffer, Esq. 1 MARTIN GLENN UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY JUDGE Before the Court is the Motion Pursuant to Fed. R. Bankr. P. 9019(a) for Entry of an Order Approving Settlement Agreement to Approve Settlement Agreement (the “Motion”), filed by James W. Giddens (the “Trustee”), as trustee for the SIPA liquidation of the business of MF Global Inc. (the “Debtor” or “MFGI”). (ECF Doc. #7.)1 The Motion seeks approval of a settlement agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) among HSBC Bank USA, N.A. (“HSBC”), Jason Fane (“Fane”), and the Trustee (collectively, the “Parties”) regarding the ownership and distribution of physical property (specifically, five gold bars and fifteen silver bars) (the “Property”). No objections have been filed to the Motion. For the reasons discussed below, the Court grants the Motion. BACKGROUND On January 23, 2012, this Court issued an order establishing a process by which former MF Global, Inc. -

2011 Annual Report

2011 Annual Report Position is many things: the indispensable, well-timed insight that turns markets into opportunities for clients; the forward-thinking, unwavering vision that creates outsized returns for shareholders; the passion for the markets that drives our people. At MF Global, our relentless pursuit of position separates us from the pack and binds us in a common purpose— to see and seize a place of advantage and prosperity for those we serve. 2 LETTER TO SHAREHOLDERS Jon S. Corzine DEAR SHAREHOLDERS, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer As I complete my first year at MF Global, I am pleased to report that the transformative steps taken by the board of directors and management to reset the firm’s business strategy are well under way. We believe that early indicators demonstrate that our new strategic direction is beginning to yield results. Our market position, revenues and bottom line all have improved over the past year. 1 On behalf of the board of directors and the management expanding global economy and new regulatory limits team, I want to thank our clients for their business and on risk and leverage are creating new demands for risk our shareholders for their ongoing support. I also want intermediation services. These factors are happening at a to recognize the dedication and commitment of our time when competitive capacity is shrinking. We believe employees. our strategic direction squarely aligns MF Global’s The transformation of MF Global from a futures competitive strengths with this evolving regulatory and and options broker to a commodities and capital financial landscape.