Chapter 6 HUMAN-ANIMAL BOND PROGRAMS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Psychiatric Service Dogs on Quality of Life and Relationship Functioning in Military-Connected Couples

Military Behavioral Health ISSN: (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/umbh20 “A Part of Our Family”? Effects of Psychiatric Service Dogs on Quality of Life and Relationship Functioning in Military-Connected Couples Christine E. McCall , Kerri E. Rodriguez , Shelley M. MacDermid Wadsworth , Laura A. Meis & Marguerite E. O’Haire To cite this article: Christine E. McCall , Kerri E. Rodriguez , Shelley M. MacDermid Wadsworth , Laura A. Meis & Marguerite E. O’Haire (2020): “A Part of Our Family”? Effects of Psychiatric Service Dogs on Quality of Life and Relationship Functioning in Military-Connected Couples, Military Behavioral Health, DOI: 10.1080/21635781.2020.1825243 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2020.1825243 Published online: 14 Oct 2020. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 39 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=umbh20 MILITARY BEHAVIORAL HEALTH https://doi.org/10.1080/21635781.2020.1825243 “ ” A Part of Our Family ? Effects of Psychiatric Service Dogs on Quality of Life and Relationship Functioning in Military-Connected Couples a b à a c Christine E. McCall , Kerri E. Rodriguez , Shelley M. MacDermid Wadsworth , Laura A. Meis , and b Marguerite E. O’Haire a Military Family Research Institute, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, College of Health and Human Sciences, b Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana; Center for the Human-Animal Bond, Department of Comparative Pathobiology, College c of Veterinary Medicine, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana; Center for Care Delivery & Outcomes Research, Minneapolis VA Health Care System, Department of Medicine, University of Minnesota Medical School, Minneapolis, Minnesota ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can have corrosive impacts on family relationships and Posttraumatic stress individual functioning. -

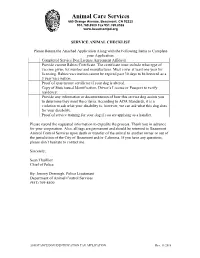

Application Along with the Following Items to Complete Your Application: Completed Service Dog License Agreement Affidavit Provide Current Rabies Certificate

Animal Care Services 660 Orange Avenue, Beaumont, CA 92223 951.769.8500 Fax 951.769.8526 www.beaumontpd.org SERVICE ANIMAL CHECKLIST Please Return the Attached Application Along with the Following Items to Complete your Application: Completed Service Dog License Agreement Affidavit Provide current Rabies Certificate. The certificate must include what type of vaccine given, lot number and manufacturer. Must cover at least one year for licensing. Rabies vaccination cannot be expired past 30 days to be honored as a 3 year vaccination. Proof of spay/neuter certificate if your dog is altered. Copy of State issued Identification, Driver’s License or Passport to verify residency. Provide any information or documentation of how this service dog assists you to determine they meet the criteria. According to ADA Standards, it is a violation to ask what your disability is; however, we can ask what this dog does for your disability. Proof of service training for your dog if you are applying as a handler. Please resend the requested information to expedite the process. Thank you in advance for your cooperation. Also, all tags are permanent and should be returned to Beaumont Animal Control Services upon death or transfer of the animal to another owner or out of the jurisdiction of the City of Beaumont and/or Calimesa. If you have any questions, please don’t hesitate to contact me. Sincerely, Sean Thuilliez Chief of Police By: Jeremy Dorrough, Police Lieutenant Department of Animal Control Services (951) 769-8500 ASSISTANCE DOG IDENTIFICATION TAG APPLICATION -

COVID-19 and THERAPY DOGS in SCHOOLS By: Sharon A

1 | PSBA ALLIANCE PARTNER | Sponsored content COVID-19 AND THERAPY DOGS IN SCHOOLS By: Sharon A. Orr Do you have therapy animals in your Do not allow people to handle items Therapy animals provide affection and school or are you looking to add that go into the dog’s mouth such comfort to members of the general them? We are still learning about as toys and treats. Disinfect high- public, typically in facility settings how COVID-19 spreads, but there touch items frequently, including such as hospitals, assisted living and have been some instances where collars, leashes, toys, therapy vests/ schools. These animals possess a it has been identified in animals. If harnesses, and food and water bowls. special aptitude for interacting with you have, or are planning to have, a Do not allow therapy dogs to lick or people. Therapy animal owners therapy animal in your school, it is “give kisses.” volunteer their time to visit facilities important to follow local guidance as with their animal. A therapy animal it relates to acceptable business and Currently, there is no evidence that has no special rights of access, except social practices. Some schools that the virus can spread to people from in those facilities where they are normally use therapy animals may the skin or fur of animals. Prior to welcomed. choose to not allow them at this time. visits, therapy animals should be If you are planning to move forward bathed/groomed with approved A therapy animal is not a service/ with a therapy animal in your facility, pet products – never use chemical assistance animal. -

Service Dog Vs. Emotional Support Vs. Therapy

SERVICE DOGS vs. EMOTIONAL SUPPORT ANIMALS vs. THERAPY ANIMALS - Includes information from the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) – www.ada.gov Each year, we have students who approach us with questions about bringing Service Dogs, Emotional Support Animals, and Therapy Animals to campus. Do you understand the differenCes between the 3 categories? WHAT IS THE DEFINITION OF A SERVICE ANIMAL? “Service animals are defined as dogs that are individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with disabilities… Service animals are workinG animals, not pets. The work or task a doG has been trained to provide must be direCtly related to the person’s disability.” Note: Specially trained miniature horses can also qualify as Service Animals, but have some additional restrictions regarding reasonable accommodations including whether or not they are housebroken, their size, safety issues, etc. Otherwise, Service Miniature Horses have the same rights as Service Dogs. SERVICE DOG TASK EXAMPLES: • GuidinG a handler that is vision impaired. • AlertinG a handler that is hearing impaired to sounds. • ProteCtinG a handler that is having a seizure or going for help. • AlertinG a handler that is about to have a seizure. • RetrievinG dropped items for or pulling a handler in a wheelChair. • ProvidinG room safety checks for a handler with severe Post TraumatiC Stress Disorder (PTSD). • RemindinG a handler who is coGnitively or developmentally disabled to take their medications. • AlertinG a handler with autism to distracting repetitive movements so that they can stop the movement. SERVICE DOG RIGHTS & RULES: Federal law allows for Service Dogs to accompany handlers in a wide range of State and local government settings, businesses, and non-profit organizations (i.e. -

Paw-Nelists Meet the Paw-Nelists

VIRTUAL PAWS April 14 11 a.m.-12:30 p.m. and 7-8 p.m. bit.ly/UMassPaws Meet the Paw-nelists Meet the Paw-nelists Ace is a black Lab mix who had a rough start in life, losing his front leg as a puppy. However, he is a happy, energetic five-year-old boy who loves to play in the snow, do tricks and give “high fives,” all for cookies of course! Annie Baker is a scruffy mixed-breed “Tibetan Spaniador,” possibly the first of her kind. She spends most of her days snuggled in one of her many beds, sometimes moving her small stuffed animals from one area to another, and always looking for a belly rub. But come walk time, this little girl will frolic and zoom with the best of them. Give Ms. Baker an open field or a long stretch of beach, and you’ll be hard pressed to find another 8-year-old dog that can outrun her! Ava is a gentle 12-year-old beagle mix who loves people, other dogs, and sweet talk. She likes to have her ears and chest rubbed and to be included in everything. Bear is almost 4 years old and came from Georgia as a rescue. His favorite activities are swimming and playing in the snow. His favorite foods are doggy ice cream and broccoli. Bernie is 3 and has a 10-month-old brother whom he tolerates. He loves fetch and can play for hours. Then he collapses into a deep sleep and no amount of prodding (barking) from Joey, his brother, will move him. -

Geographic Distribution of Echinococcosis in Tibetan Region Of

Liu et al. Infectious Diseases of Poverty (2018) 7:104 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-018-0486-4 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Geographic distribution of echinococcosis in Tibetan region of Sichuan Province, China Lei Liu1†, Bing Guo2†, Wei Li3†, Bo Zhong1*, Wen Yang1, Shu-Cheng Li4, Qian Wang1, Xing Zhao2, Ke-Jun Xu3, Sheng-Chao Qin4, Yan Huang1, Wen-Jie Yu1, Wei He1, Sha Liao1 and Qi Wang1 Abstract Background: Echinococcosis is a parasitic zoonosis caused by Echinococcus larvae parasitism causing high mortality. The Tibetan Region of Sichuan Province is a high prevalence area for echinococcosis in China. Understanding the geographic distribution pattern is necessary for precise control and prevention. In this study, a spatial analysis was conducted to explore the town-level epidemiology of echinococcosis in the Sichuan Tibetan Region and to provide guidance for formulating regional prevention and control strategies. Methods: The study was based on reported echinococcosis cases by the end of 2017, and each case was geo-coded at the town level. Spatial empirical Bayes smoothing and global spatial autocorrelation were used to detect the spatial distribution pattern. Spatial scan statistics were applied to examine local clusters. Results: The spatial distribution of echinococcosis in the Sichuan Tibetan Region was mapped at the town level in terms of the crude prevalence rate, excess hazard and spatial smoothed prevalence rate. The spatial distribution of echinococcosis was non-random and clustered with the significant global spatial autocorrelation (I = 0.7301, P =0.001). Additionally, five significant spatial clusters were detected through the spatial scan statistic. Conclusions: There was evidence for the existence of significant echinococcosis clusters in the Tibetan Region of Sichuan Province, China. -

Dog Breeds of the World

Dog Breeds of the World Get your own copy of this book Visit: www.plexidors.com Call: 800-283-8045 Written by: Maria Sadowski PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors 4523 30th St West #E502 Bradenton, FL 34207 http://www.plexidors.com Dog Breeds of the World is written by Maria Sadowski Copyright @2015 by PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors Published in the United States of America August 2015 All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording, or by any information retrieval and storage system without permission from PlexiDor Performance Pet Doors. Stock images from canstockphoto.com, istockphoto.com, and dreamstime.com Dog Breeds of the World It isn’t possible to put an exact number on the Does breed matter? dog breeds of the world, because many varieties can be recognized by one breed registration The breed matters to a certain extent. Many group but not by another. The World Canine people believe that dog breeds mostly have an Organization is the largest internationally impact on the outside of the dog, but through the accepted registry of dog breeds, and they have ages breeds have been created based on wanted more than 340 breeds. behaviors such as hunting and herding. Dog breeds aren’t scientifical classifications; they’re It is important to pick a dog that fits the family’s groupings based on similar characteristics of lifestyle. If you want a dog with a special look but appearance and behavior. Some breeds have the breed characterics seem difficult to handle you existed for thousands of years, and others are fairly might want to look for a mixed breed dog. -

Aavmc Guidelines for Service Animal Access to Veterinary Teaching Facilities

AAVMC POLICY GUIDELINE activities of normal living. The Americans with Disabilities Act AAVMC GUIDELINES (ADA) defines service animals as any “dog or miniature horse FOR SERVICE ANIMAL individually trained to do work or perform tasks directly related to the partner’s disability, including, but not limited to, guiding ACCESS TO VETERINARY individuals with impaired vision, alerting individuals who are hearing impaired to intruders or sounds, providing non-violent TEACHING FACILITIES protection or rescue work, pulling a wheelchair, fetching dropped items, assisting an individual during a seizure, alerting August 2, 2019 individuals to the presence of allergens, or helping persons with psychiatric and neurological disabilities by preventing or interrupting impulsive or destructive behaviors.” If an animal meets this definition, it is considered a service animal regardless of whether it has undergone formal training and INTRODUCTION AND certification or has been licensed or certified by a state or local SERVICE DOG DEFINITIONS government. The term psychiatric service dog is sometimes Introduction Hospital staff and students in the teaching hospital may not Because definitions of service animals be well informed about service animals and their legal status, and the benefits they provide to persons with disabilities. and emotional support animals are Because definitions of service animals and emotional support animals are not well understood by many, and the systems for not well understood by many, and the identifying and training service animals are not standardized or codified, society will often look to veterinarians for assistance systems for identifying and training with issues in this arena. Veterinary students and staff of veterinary teaching facilities should be well informed of the service animals are not standardized definitions of a service animal and emotional support animal and the legal differences between them. -

ALLIANCE of THERAPY DOGS RULES and REGULATIONS Part I GOVERNING MEMBER GUIDELINES

ALLIANCE OF THERAPY DOGS RULES AND REGULATIONS Part I GOVERNING MEMBER GUIDELINES Failure to adhere to the ATD Governing Member Guidelines, Code of Ethics or Policies will jeopardize your membership. I. The organization: 1. ATD is a non-profit, all-volunteer organization. We do not accept monetary reimbursement for any of the services our members provide. Donations are welcome. All requests to use the registered ATD name, logo, or slogan must be submitted in writing to the president. The requestor will be notified in writing whether or not permission is granted. Permission to add the link www.therapydogs.com to a personal website is not needed. Permission to add the logo and link will not be granted to any for-profit websites. 2. Membership is a privilege, not a right, granted by the ATD Board of Directors through the various committees appointed to represent and protect the interests and safety of the organization. 3. Annual review: Members must pass an annual member review which shows their familiarity with the ATD rules. Renewals will not be finalized until 100% accuracy is achieved. II. Description of therapy work; requirements for members and dogs: 4. Members: Any person, aged 18 or older, may be tested with a dog and apply for membership. Anyone aged 12 through 17 may be tested with a dog to become a junior member. 5. Dogs: Any breed or mixed breed of dog, aged one year or older, may be tested with a handler to become a registered therapy dog. For insurance reasons, ATD cannot register wolves or wolf-hybrids or coyotes or coyote-hybrids because the rabies vaccination has not been proven to be effective with these animals. -

Hero Dogs White Paper Working Dogs: Building Humane Communities with Man’S Best Friend

Hero Dogs White Paper Working Dogs: Building Humane Communities with Man’s Best Friend INTRODUCTION Humankind has always had a special relationship with canines. For thousands of years, dogs have comforted us, protected us, and given us their unconditional love. Time and time again through the ages they have proven why they are considered our best friends. Yet, not only do dogs serve as our beloved companions, they are also a vital part of keeping our communities healthy, safe and humane. American Humane Association has recognized the significant contributions of working dogs over the past five years with our annual Hero Dog Awards® national campaign. Dogs are nominated in multiple categories from communities across the country, with winners representing many of the working dog categories. The American Humane Association Hero Dog Awards are an opportunity to educate many about the contributions of working dogs in our daily lives. This paper provides further background into their contributions to building humane communities. Dogs have served as extensions of human senses and abilities throughout history and, despite advancements in technology, they remain the most effective way to perform myriad tasks as working dogs. According to Helton (2009a, p. 5), “the role of working dogs in society is far greater than most people know and is likely to increase, not diminish, in the future.” Whether it’s a guide dog leading her sight-impaired handler, a scent detection dog patrolling our airports, or a military dog in a war zone searching for those who wish to do us harm, working dogs protect and enrich human lives. -

I NH C a Ni Ne Assistance I NH the Intent of This Policy Is to Clarify The

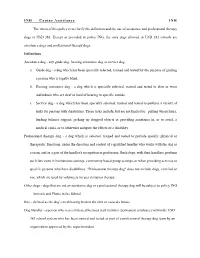

I NH C a ni ne Assistance I NH The intent of this policy is to clarify the definition and the use of assistance and professional therapy dogs in USD 383. Except as provided in policy ING, the only dogs allowed in USD 383 schools are assistance dogs and professional therapy dogs. Definitions Assistance dog - any guide dog, hearing assistance dog or service dog. a. Guide dog - a dog which has been specially selected, trained and tested for the purpose of guiding a person who is legally blind. b. Hearing assistance dog - a dog which is specially selected, trained and tested to alert or warn individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing to specific sounds. c. Service dog - a dog which has been specially selected, trained and tested to perform a variety of tasks for persons with disabilities. These tasks include, but are not limited to: pulling wheelchairs, lending balance support, picking up dropped objects or providing assistance in, or to avoid, a medical crisis, or to otherwise mitigate the effects of a disability. Professional therapy dog - a dog which is selected, trained and tested to provide specific physical or therapeutic functions, under the direction and control of a qualified handler who works with the dog as a team, and as a part of the handler's occupation or profession. Such dogs, with their handlers, perform such functions in institutional settings, community based group settings, or when providing services to specific persons who have disabilities. "Professional therapy dog" does not include dogs, certified or not, which are used by volunteers for pet visitation therapy. -

Emotional Support Animal (ESA)

International Association of Canine Professionals Service Dog Committee HUD Assistance Animal and Emotional Support Animal definitions vs DOJ Service Dog (SD) Definition At this time, the IACP acknowledges the only country that we are aware of recognizing ESAs is the United States and therefore, the rules and regulations contained in this document are those of the United States. Service animals are defined as dogs (and sometimes miniature horses) individually trained to do work or perform tasks for people with physical, sensory, psychiatric, intellectual or other mental disability. The tasks may include pulling a wheelchair, retrieving dropped items, alerting a person to a sound, guiding a person who is visually impaired, warning and/or aiding the person prior to an imminent seizure, as well as calming or interrupting a behavior of a person who suffers from Post-Traumatic Stress. The tasks a service dog can perform are not limited to this list. However, the work or task a service dog does must be directly related to the person's disability and must be trained and not inherent. Service dogs may accompany persons with disabilities into places that the public normally goes, even if they have a “No Pets” policy. These areas include state and local government buildings, businesses open to the public, public transportation, and non-profit organizations open to the public. The law allowing public access for a person with a disability accompanied by a Service Dog is the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) under the Department of Justice. Examples of Types of Service Dogs: · Guide Dog or Seeing Eye® Dog is a carefully trained dog that serves as a travel tool for persons who have severe visual impairments or are blind.