Middle and Late Pleistocene Environmental History of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 2020 Updated At: 12:34 AM 28Th January 2020

March 2020 Updated at: 12:34 AM 28th January 2020 Aylesbury Rides Sec: Philip Baronius e-mail: Secretary: Peter Robinson e-mail: Website: www.southbuckscycling.org.uk/aylesbury March Class Time Meet Elevenses Lunch Leader Sun 1 E 9:30am Weston Turville Stores College Lake Wildlife Centre Chosen on the day Sun 1 E/M 9:30am Weston Turville Stores Coffee Barn, near Soulbury Rachael C Sun 1 M 9:30am Weston Turville Stores Rushmere Country Park Chosen on the day Sun 8 E 9:30am Watermead Inn, Aylesbury Lakers Nursery, Winslow Paula J Sun 8 E/M 9:30am Watermead Inn, Aylesbury NT Café, Stowe Yvonne R Sun 8 M 9:30am Watermead Inn, Aylesbury Twyford Village Stores Chosen on the day Sun 15 E 9:30am Stoke Mandeville Combined School Hearing Dogs Café, Saunderton Nicholas V Sun 15 E/M 9:30am Stoke Mandeville Combined School Waterperry Gardens Doug W Sun 15 M 9:30am Stoke Mandeville Combined School Waterperry Gardens Chosen on the day Sun 22 E 9:30am Wendover Clock Tower Potten End Village Store Nick B Sun 22 E/M 9:30am Wendover Clock Tower Caffè Nero, Chesham Chosen on the day Sun 22 M 9:30am Wendover Clock Tower Hearing Dogs Café, Saunderton Chosen on the day Sun 29 E 9:30am Café in the Park, Aston Clinton Tower Hill GC, Chipperfield Richard G Sun 29 E/M 9:30am Café in the Park, Aston Clinton NT Café, Dunstable Downs Chosen on the day Sun 29 M 9:30am Café in the Park, Aston Clinton NT Café, Dunstable Downs Philip B Aylesbury Social Evening - second Tuesday of the month 7:30pm Tue 10 S 7:30pm Kings Head, Aylesbury Peter R Chiltern Hills Rides Sec: -

Manor Farm Barn Web Brochure

MANOR FARM BARN WINGRAVE• HP22 MANOR FARM BARN WINGRAVE • HP22 Superb Grade II listed barn in a beautiful setting Sitting room • Dining room Kitchen/breakfast room • Cloakroom Master bedroom with en suite bathroom Three further bedrooms • Family bathroom Detached double garage • Gardens Mentmore 2 miles • Leighton Buzzard station 5 miles ﴿London Euston 33 minutes﴾ Wendover station 10 miles ﴿London Marylebone 52 minutes﴾ Tring 7 miles • Aylesbury 6 miles • Berkhamsted 15 miles ﴿all times and distances are approximate﴾ These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Manor Farm Barn Located within a small development in the popular village of Wingrave, this superb Grade II listed barn conversion is beautifully presented and sits in attractive gardens. Of particular note is the wonderful open plan sitting/dining room. The space is enhanced by a vaulted ceiling with exposed timbers and inglenook rising beyond the galleried landing, creating a striking focal point. From here, French doors open to the gardens along with access to a family/dining room. The kitchen/breakfast room has a country theme, with wooden cabinets and butler sink and gives access to the boot room and cloakroom. Upstairs, a study area makes the most of the galleried landing space and provides an outlook across the substantial reception room below. There are four bedrooms, the master with a range of fitted wardrobes and en suite bathroom with separate shower. Situation Manor Farm Barn is situated in picturesque Wingrave, an attractive village with an active community, directly opposite the village Church. -

The Hidation of Buckinghamshire. Keith Bailey

THE HIDA TION OF BUCKINGHAMSHIRE KEITH BAILEY In a pioneering paper Mr Bailey here subjects the Domesday data on the hidation of Buckinghamshire to a searching statistical analysis, using techniques never before applied to this county. His aim is not explain the hide, but to lay a foundation on which an explanation may be built; to isolate what is truly exceptional and therefore calls for further study. Although he disclaims any intention of going beyond analysis, his paper will surely advance our understanding of a very important feature of early English society. Part 1: Domesday Book 'What was the hide?' F. W. Maitland, in posing purposes for which it may be asked shows just 'this dreary old question' in his seminal study of how difficult it is to reach a consensus. It is Domesday Book,1 was right in saying that it almost, one might say, a Holy Grail, and sub• is in fact central to many of the great questions ject to many interpretations designed to fit this of early English history. He was echoed by or that theory about Anglo-Saxon society, its Baring a few years later, who wrote, 'the hide is origins and structures. grown somewhat tiresome, but we cannot well neglect it, for on no other Saxon institution In view of the large number of scholars who have we so many details, if we can but decipher have contributed to the subject, further discus• 2 them'. Many subsequent scholars have also sion might appear redundant. So it would be directed their attention to this subject: A. -

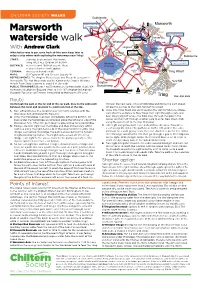

Marsworth Waterside Walk

CHILTERN SOCIETY WALKS Gubblecote Grand Union Canal H Marsworth (Aylesbury Arm) 8 Marsworth B489 Bus stops Grand Union Canal Startop’s G Start/Finish waterside walk 7 End Wilstone P 1 2 Tringford A B With Andrew Clark Marsworth C What better way to get some fresh air into your lungs than to Alternative Reservoir B488 P Wilstone Route Back enjoy a crisp winter walk exploring the waterways near Tring? 6 Green B489 E Bulbourne START: Startops End car park, Marsworth, Tringford Tring HP23 4LJ. Grid ref SP 919 141 Reservoir Grand Union Canal Wilstone F (Wendover Arm) DISTANCE: 4.7 miles with 160ft of ascent. There Reservoir 3 is also a shorter 3 mile option 4 Little Tring D TERRAIN: An easy waterside walk 5 Farm Tring Wharf MAPS: OS Explorer 181 and Chiltern Society 18 REFRESHMENTS: The Anglers Retreat pub and Bluebells tearoom in Marsworth. The Half Moon pub and the Community Shop in Wilstone. New Mill Mead’s Farm Shop tearoom at point 6 of the walk Drayton PUBLIC TRANSPORT: Buses – no.50 Aylesbury to Marsworth (Sun); 164 Beauchamp Aylesbury to Leighton Buzzard (Mon to Sat); 167 Ivinghoe to Leighton 0 0.5 1km B488 B486 Buzzard (Tue only); 207 Hemel Hempstead to Marsworth (Fri only). 0 mile½ North Tring Map: Glyn Kuhn Route Go through the gate at the far end of the car park. Stay on the wide path through the next gate, cross a footbridge and follow the path ahead. between the canal and reservoir to a path junction at the top. Where this swings to the right, fork left to a road. -

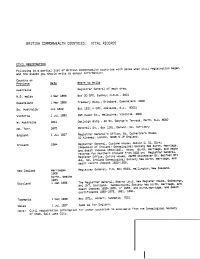

British Isles

BRITISH COMMONWEALTH COUNTRIES: VITAL RECORDS CIVIL REGISTRATICN Following is a partial list of British Ccmmcnwealth countries with dates when civil registration began, and the places you should writ~ to obtain information: Ccuntry or Prevince Q!!! Where to Write .Au$t'ralia Registrar Ganer-a! of each area. N.S. wales 1 Mar 1856 Sex 30 GPO, Sydney, N.S.W., 2001 Queensland 1 Mar 1856 Treasury Bldg., Brisbane, Queensland 4000 So. Australia Jul 1842 8ex 1531 H Gr\), Adelaide, S.A. 5CCCl Victoria 1 Jul 1853 295 Cuesn St., Melbourne, Victoria XCO W. .Australia 1841 Cak!eigh 61dg., 22 St. Gear-ge's Terrace, Perth, W.A. eoco Nc. Terr. 1870 Mitchell St., Box 1281. OarNin, Nc. Territory England 1 Jul 1837 Registrar General's Office, St. catherine's House, 10 Kinsway. Loncen, 'AC2S 6 JP England. Ireland 1864 Registrar General, Custcme House. Dublin C. 10, Eire, (Recuolic(Republic of Ireland) Genealogical Society has bir~h, marriage, and death indexes 1864-1921. Nete: Birth, rtarl"'iage,rmt'l"'iage, atld death records farfor Nor~hern Ireland frcm 1922 an: Registrar General, Regis~erOffice, Oxford House. 49~5 Chichester St. Selfast STI 4HL, No~ !re1.a.rld Genealcgical Scciety has birth, narriage, and death recordreccrd indexes 1922-l959~ New Z!!aland marriages Registrar General, P.O~ Sox =023, wellingtcn, New Zealand. 1008 birth, deaths 1924 Scotland 1 Jan 1855 The Registrar General, Search Unit, New Register House, Edinburgh, EHl 3YT, SCCtland~ Genealogical Saei~tyScei~ty has bir~h,birth, marriage, and death indexes 1855-1955, or 1956, and birt%'\ crarriage, and death cer~ificates 1855-1875, 1881. -

LCA 10.3 Marsworth and Pitstone Chalk Quarries Landscape

Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.3 Marsworth and Pitstone Chalk Quarries Landscape Character Type: LCT 10 Chalk Foothills B0404200/LAND/01 Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.3 Marsworth and Pitstone Chalk Quarries (LCT 10) Key Characteristics Location The area lies within the eastern part of the Tring Gap slightly to the northeast of the town of Tring. It includes the settlement of Marsworth in • Shallow sloping chalk the west and to the northeast the boundary is formed by the southern edge foothills of Pitstone and Ivinghoe. The eastern boundary follows the B488 which also • Extensive areas of chalk runs along the edge of the foothills. The western boundary, which is also the quarrying county boundary, incorporates the eastern shoreline to the Marsworth • Restored chalk pits Reservoir and the Grand Union Canal. under grassland management Landscape character An area of gently rolling chalk hills, that overall, falls • Open arable landscape from south to north within which a large area of disturbance remains on periphery of area resulting from the previous excavations of chalk pits and the former cement • Chalk springs draining works site since removed. Land has been restored to grassland use and off the upper slopes peripheral areas outside the areas of disturbance are in arable. Land restoration and management of College Lake pit has created a wildlife centre. The cement works site has now been developed as housing and an Distinctive Features industrial complex. Those fields on the eastern flank of the LCA are large prairie fields often with well trimmed hedges. -

Views of the Vale Walks.Cdr

About the walk Just a 45 minute train ride from London Marylebone and a few minutes walk from Wendover station you can enjoy the fresh air and fantastic views of the Chilterns countryside. These two walks take you to the top of the Chiltern Hills, through ancient beech woods, carpets of bluebells and wild flowers. There are amazing views of the Aylesbury Vale and Chequers, the Prime Minister's country home. You might also see rare birds such as red kites and firecrests and the tiny muntjac deer. 7 Wendover Woods – this is the habitat of the rare Firecrest, the smallest bird in Europe, which nests in the Norway spruce. You can finish your walk with a tasty meal, pint of beer or a This is also the highest point in the Chilterns (265m). The cup of tea. woods are managed by Forest Enterprise who have kindly granted access to those trails that are not public rights of way. Walking gets you fit and keeps you healthy!! 8 Boddington hillfort. This important archaeological site was occupied during the 1st century BC. Situated on top of the hill, the fort would have provided an excellent vantage point and defensive position for its Iron Age inhabitants. In the past the hill was cleared of trees for grazing animals. Finds have included a bronze dagger, pottery and a flint scraper. 9 Coldharbour cottages – were part of Anne Boleyn's dowry to Henry VIII. 4 Low Scrubs. This area of woodland is special and has a 10 Red Lion Pub – built in around 1620. -

LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type

Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills Landscape Character Type: LCT 10 Chalk Foothills B0404200/LAND/01 Aylesbury Vale District Council & Buckinghamshire County Council Aylesbury Vale Landscape Character Assessment LCA 10.2 Ivinghoe Foothills (LCT 10) Key Characteristics Location An extensive area of land which surrounds the Ivinghoe Beacon including the chalk pit at Pitstone Hill to the west and the Hemel Hempstead • Chalk foothills Gap to the east. The eastern and western boundaries are determined by the • Steep sided dry valleys County boundary with Hertfordshire. • Chalk outliers • Large open arable fields Landscape character The LCA comprises chalk foothills including dry • Network of local roads valleys and lower slopes below the chalk scarp. Also included is part of the • Scattering of small former chalk pits at Pitstone and at Ivinghoe Aston. The landscape is one of parcels of scrub gently rounded chalk hills with scrub woodland on steeper slopes, and woodland predominantly pastoral use elsewhere with some arable on flatter slopes to • Long distance views the east. At Dagnall the A4146 follows the gap cut into the Chilterns scarp. over the vale The LCA is generally sparsely settled other than at the Dagnall Gap. The area is crossed by the Ridgeway long distance footpath (to the west). The • Smaller parcels of steep sided valley at Coombe Hole has been eroded by spring. grazing land adjacent to settlements Geology The foothills are made up of three layers of chalk. The west Melbury marly chalk overlain by a narrow layer of Melbourn Rock which in turn is overlain by Middle Chalk. -

History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group

History of Meteorology and Physical Oceanography Special Interest Group Newsletter 2, 2008 pen portraits of presidents and some of the A VIEW FROM THE CHAIR profiles of interesting meteorologists that have I became your chairman again twelve months been published in Weather were commissioned ago. Many of you will remember that I chaired the by – and a number written by – Group members. Group right through the 1990s. None of you can And the Group oversees the series of dispute that I am now nineteen years older than I monographs known as Occasional Papers on was in 1989, when I first became the Group’s Meteorological History. We also publish a chairman. I must say here and now, therefore, newsletter, which I hope you find interesting. that I do not propose to remain chairman for Three have been published in the past year. Do, another decade, even if you wish me to. please, send us snippets or longer pieces for the I am very keen to see a growth in membership of newsletter. We want it to be your newsletter. the Group, and we have, indeed, welcomed new The Group’s meetings are highlights of every members during the past year. But I should like year, no less the past year, when three great to see a massive growth in membership. Some meetings were held, one in March, the others in branches of history have seen tremendous September. The one in March, held at Harris growth in recent years, especially family history; Manchester College, Oxford, was the second of and it seems clear from the popularity of TV two meetings concerned with Meteorology and history programmes, and the growth in World War I. -

Age 25 Army Unit 3Rd Brigade Canadian Field Artillery Enlisted: January 1915 in Canadian Expeditionary Force

Arthur Kempster Corporal - Service No. 42703 - Age 25 Army Unit 3rd Brigade Canadian Field Artillery Enlisted: January 1915 in Canadian Expeditionary Force Arthur was born on the 8th May 1893 in Wingrave. The son of George and Sarah (nee Jakeman) Kempster, he was brought up in Crafton with 6 other children, his father was a shepherd. In 1911 he and his brother were butcher’s assistants in Wealdstone, Middlesex. He died on the 19th November 1918 from mustard gas and influenza. He is buried in Wingrave Congregational Chapel Yard and is also commemorated at All Saints, Wing. His brother, Harry Fredrick Kempster was born in Wingrave in 1890. He died on the 2nd October 1917 in Flanders, Belgium. Harry was a rifleman with the Royal Irish Rifles, 7th Battalion. Whilst killed in action, he is not mentioned on the Mentmore War Memorial. © Mentmore Parish History Group. With thanks to Andy Cooke, John Smith (Cheddington History Soc), Lynda Sharp and Karen Thomas for research and information. Ernest Taylor Private - Service No. 29168 - Age 30 6th Battalion Duke of Wellington’s [West Riding] Regiment. Enlisted: Huddersfield Died July 27th 1918, in the No 3 Australian Causality Clearing station, Brandhoek. Suffered gunshot wounds to his back, forehead and neck. Buried Esquelbecq Military Cemetery III D 14. Born 1887 Cheddington, Son of William and Mary (nee Baker) Taylor Ernest married Elizabeth Kelly (nee Firth). Elizabeth was a widow with four small children. The couple met and married in Huddersfield and had a child of their own on 11th Nov 1916. Ernest had worked on a local farm in Cheddington then he moved to Huddersfield where he became a goods porter. -

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015

Aylesbury Vale Community Chest Grants April 2014 - March 2015 Amount Granted Total Cost Award Aylesbury Vale Ward Name of Organisation £ £ Date Purpose Area Buckinghamshire County Local Areas Artfully Reliable Theatre Society 1,000 1,039 Sep-14 Keyboard for rehearsals and performances Aston Clinton Wendover Aylesbury & District Table Tennis League 900 2,012 Sep-14 Wall coverings and additional tables Quarrendon Greater Aylesbury Aylesbury Astronomical Society 900 3,264 Aug-14 new telescope mount to enable more community open events and astrophotography Waddesdon Waddesdon/Haddenham Aylesbury Youth Action 900 2,153 Jul-14 Vtrek - youth volunteering from Buckingham to Aylesbury, August 2014 Vale West Buckingham/Waddesdon Bearbrook Running Club 900 1,015 Mar-15 Training and raceday equipment Mandeville & Elm Farm Greater Aylesbury Bierton with Broughton Parish Council 850 1,411 Aug-14 New goalposts and goal mouth repairs Bierton Greater Aylesbury Brill Memorial Hall 1,000 6,000 Aug-14 New internal and external doors to improve insulation, fire safety and security Brill Haddenham and Long Crendon Buckingham and District Mencap 900 2,700 Feb-15 Social evenings and trip to Buckingham Town Pantomime Luffield Abbey Buckingham Buckingham Town Cricket Club 900 1,000 Feb-15 Cricket equipment for junior section Buckingham South Buckingham Buckland and Aston Clinton Cricket Club 700 764 Jun-14 Replacement netting for existing practice net frames Aston Clinton Wendover Bucks Play Association 955 6,500 Apr-14 Under 5s area at Play in The Park event -

Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes Listed Below (Aylesbury Area)

NOTICE OF ELECTION Buckinghamshire Council Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below (Aylesbury Area) Number of Parish Parishes Councillors to be elected Adstock Parish Council 7 Akeley Parish Council 7 Ashendon Parish Council 5 Aston Abbotts Parish Council 7 Aston Clinton Parish Council 11 Aylesbury Town Council for Bedgrove ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Central ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Coppice Way ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Elmhurst ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Gatehouse ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Hawkslade ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Mandeville & Elm Farm ward 3 Aylesbury Town Council for Oakfield ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Oxford Road ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Quarrendon ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Southcourt ward 2 Aylesbury Town Council for Walton Court ward 1 Aylesbury Town Council for Walton ward 1 Beachampton Parish Council 5 Berryfields Parish Council 10 Bierton Parish Council for Bierton ward 8 Bierton Parish Council for Oldhams Meadow ward 1 Brill Parish Council 7 Buckingham Park Parish Council 8 Buckingham Town Council for Highlands & Watchcroft ward 1 Buckingham Town Council for North ward 7 Buckingham Town Council for South ward 8 Buckingham Town Council form Fishers Field ward 1 Buckland Parish Council 7 Calvert Green Parish Council 7 Charndon Parish Council 5 Chearsley Parish Council 7 Cheddington Parish Council 8 Chilton Parish Council 5 Coldharbour Parish Council 11 Cublington Parish Council 5 Cuddington Parish Council 7 Dinton with Ford &