E34.Full.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of Carbon Monoxide Intoxication

medicina Review The History of Carbon Monoxide Intoxication Ioannis-Fivos Megas 1 , Justus P. Beier 2 and Gerrit Grieb 1,2,* 1 Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, Gemeinschaftskrankenhaus Havelhoehe, Kladower Damm 221, 14089 Berlin, Germany; fi[email protected] 2 Burn Center, Department of Plastic Surgery and Hand Surgery, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Intoxication with carbon monoxide in organisms needing oxygen has probably existed on Earth as long as fire and its smoke. What was observed in antiquity and the Middle Ages, and usually ended fatally, was first successfully treated in the last century. Since then, diagnostics and treatments have undergone exciting developments, in particular specific treatments such as hyperbaric oxygen therapy. In this review, different historic aspects of the etiology, diagnosis and treatment of carbon monoxide intoxication are described and discussed. Keywords: carbon monoxide; CO intoxication; COHb; inhalation injury 1. Introduction and Overview Intoxication with carbon monoxide in organisms needing oxygen for survival has probably existed on Earth as long as fire and its smoke. Whenever the respiratory tract of living beings comes into contact with the smoke from a flame, CO intoxication and/or in- Citation: Megas, I.-F.; Beier, J.P.; halation injury may take place. Although the therapeutic potential of carbon monoxide has Grieb, G. The History of Carbon also been increasingly studied in recent history [1], the toxic effects historically dominate a Monoxide Intoxication. Medicina 2021, 57, 400. https://doi.org/10.3390/ much longer period of time. medicina57050400 As a colorless, odorless and tasteless gas, CO is produced by the incomplete combus- tion of hydrocarbons and poses an invisible danger. -

Pathophysiology of Acid Base Balance: the Theory Practice Relationship

Intensive and Critical Care Nursing (2008) 24, 28—40 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Pathophysiology of acid base balance: The theory practice relationship Sharon L. Edwards ∗ Buckinghamshire Chilterns University College, Chalfont Campus, Newland Park, Gorelands Lane, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire HP8 4AD, United Kingdom Accepted 13 May 2007 KEYWORDS Summary There are many disorders/diseases that lead to changes in acid base Acid base balance; balance. These conditions are not rare or uncommon in clinical practice, but every- Arterial blood gases; day occurrences on the ward or in critical care. Conditions such as asthma, chronic Acidosis; obstructive pulmonary disease (bronchitis or emphasaemia), diabetic ketoacidosis, Alkalosis renal disease or failure, any type of shock (sepsis, anaphylaxsis, neurogenic, cardio- genic, hypovolaemia), stress or anxiety which can lead to hyperventilation, and some drugs (sedatives, opoids) leading to reduced ventilation. In addition, some symptoms of disease can cause vomiting and diarrhoea, which effects acid base balance. It is imperative that critical care nurses are aware of changes that occur in relation to altered physiology, leading to an understanding of the changes in patients’ condition that are observed, and why the administration of some immediate therapies such as oxygen is imperative. © 2007 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction the essential concepts of acid base physiology is necessary so that quick and correct diagnosis can The implications for practice with regards to be determined and appropriate treatment imple- acid base physiology are separated into respi- mented. ratory acidosis and alkalosis, metabolic acidosis The homeostatic imbalances of acid base are and alkalosis, observed in patients with differing examined as the body attempts to maintain pH bal- aetiologies. -

Ethylene Glycol Ingestion Reviewer: Adam Pomerlau, MD Authors: Jeff Holmes, MD / Tammi Schaeffer, DO

Pediatric Ethylene Glycol Ingestion Reviewer: Adam Pomerlau, MD Authors: Jeff Holmes, MD / Tammi Schaeffer, DO Target Audience: Emergency Medicine Residents, Medical Students Primary Learning Objectives: 1. Recognize signs and symptoms of ethylene glycol toxicity 2. Order appropriate laboratory and radiology studies in ethylene glycol toxicity 3. Recognize and interpret blood gas, anion gap, and osmolal gap in setting of TA ingestion 4. Differentiate the symptoms and signs of ethylene glycol toxicity from those associated with other toxic alcohols e.g. ethanol, methanol, and isopropyl alcohol Secondary Learning Objectives: detailed technical/behavioral goals, didactic points 1. Perform a mental status evaluation of the altered patient 2. Formulate independent differential diagnosis in setting of leading information from RN 3. Describe the role of bicarbonate for severe acidosis Critical actions checklist: 1. Obtain appropriate diagnostics 2. Protect the patient’s airway 3. Start intravenous fluid resuscitation 4. Initiate serum alkalinization 5. Initiate alcohol dehydrogenase blockade 6. Consult Poison Center/Toxicology 7. Get Nephrology Consultation for hemodialysis Environment: 1. Room Set Up – ED acute care area a. Manikin Set Up – Mid or high fidelity simulator, simulated sweat if available b. Airway equipment, Sodium Bicarbonate, Nasogastric tube, Activated charcoal, IV fluid, norepinephrine, Simulated naloxone, Simulate RSI medications (etomidate, succinylcholine) 2. Distractors – ED noise For Examiner Only CASE SUMMARY SYNOPSIS OF HISTORY/ Scenario Background The setting is an urban emergency department. This is the case of a 2.5-year-old male toddler who presents to the ED with an accidental ingestion of ethylene glycol. The child was home as the father was watching him. The father was changing the oil on his car. -

Acid-Base Physiology & Anesthesia

ACID-BASE PHYSIOLOGY & ANESTHESIA Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA Introductions • Abnormal acid-base changes are a result of a disease process. They are not the disease. • Abnormal acid base disorder predicts the outcome of the case but often is not a direct cause of the mortality, but rather is an epiphenomenon. • Disorders of acid base balance result from disorders of primary regulating organs (lungs or kidneys etc), exogenous drugs or fluids that change the ability to maintain normal acid base balance. • An acid is a hydrogen ion or proton donor, and a substance which causes a rise in H+ concentration on being added to water. • A base is a hydrogen ion or proton acceptor, and a substance which causes a rise in OH- concentration when added to water. • Strength of acids or bases refers to their ability to donate and accept H+ ions respectively. • When hydrochloric acid is dissolved in water all or almost all of the H in the acid is released as H+. • When lactic acid is dissolved in water a considerable quantity remains as lactic acid molecules. • Lactic acid is, therefore, said to be a weaker acid than hydrochloric acid, but the lactate ion possess a stronger conjugate base than hydrochlorate. • The stronger the acid, the weaker its conjugate base, that is, the less ability of the base to accept H+, therefore termed, ‘strong acid’ • Carbonic acid ionizes less than lactic acid and so is weaker than lactic acid, therefore termed, ‘weak acid’. • Thus lactic acid might be referred to as weak when considered in relation to hydrochloric acid but strong when compared to carbonic acid. -

Parenteral Nutrition Primer: Balance Acid-Base, Fluid and Electrolytes

Parenteral Nutrition Primer: Balancing Acid-Base, Fluids and Electrolytes Phil Ayers, PharmD, BCNSP, FASHP Todd W. Canada, PharmD, BCNSP, FASHP, FTSHP Michael Kraft, PharmD, BCNSP Gordon S. Sacks, Pharm.D., BCNSP, FCCP Disclosure . The program chair and presenters for this continuing education activity have reported no relevant financial relationships, except: . Phil Ayers - ASPEN: Board Member/Advisory Panel; B Braun: Consultant; Baxter: Consultant; Fresenius Kabi: Consultant; Janssen: Consultant; Mallinckrodt: Consultant . Todd Canada - Fresenius Kabi: Board Member/Advisory Panel, Consultant, Speaker's Bureau • Michael Kraft - Rockwell Medical: Consultant; Fresenius Kabi: Advisory Board; B. Braun: Advisory Board; Takeda Pharmaceuticals: Speaker’s Bureau (spouse) . Gordon Sacks - Grant Support: Fresenius Kabi Sodium Disorders and Fluid Balance Gordon S. Sacks, Pharm.D., BCNSP Professor and Department Head Department of Pharmacy Practice Harrison School of Pharmacy Auburn University Learning Objectives Upon completion of this session, the learner will be able to: 1. Differentiate between hypovolemic, euvolemic, and hypervolemic hyponatremia 2. Recommend appropriate changes in nutrition support formulations when hyponatremia occurs 3. Identify drug-induced causes of hypo- and hypernatremia No sodium for you! Presentation Outline . Overview of sodium and water . Dehydration vs. Volume Depletion . Water requirements & Equations . Hyponatremia • Hypotonic o Hypovolemic o Euvolemic o Hypervolemic . Hypernatremia • Hypovolemic • Euvolemic • Hypervolemic Sodium and Fluid Balance . Helpful hint: total body sodium determines volume status, not sodium status . Examples of this concept • Hypervolemic – too much volume • Hypovolemic – too little volume • Euvolemic – normal volume Water Distribution . Total body water content varies from 50-70% of body weight • Dependent on lean body mass: fat ratio o Fat water content is ~10% compared to ~75% for muscle mass . -

The Role of Hypercapnia in Acute Respiratory Failure Luis Morales-Quinteros1* , Marta Camprubí-Rimblas2,4, Josep Bringué2,9, Lieuwe D

Morales-Quinteros et al. Intensive Care Medicine Experimental 2019, 7(Suppl 1):39 Intensive Care Medicine https://doi.org/10.1186/s40635-019-0239-0 Experimental REVIEW Open Access The role of hypercapnia in acute respiratory failure Luis Morales-Quinteros1* , Marta Camprubí-Rimblas2,4, Josep Bringué2,9, Lieuwe D. Bos5,6,7, Marcus J. Schultz5,7,8 and Antonio Artigas1,2,3,4,9 From The 3rd International Symposium on Acute Pulmonary Injury Translational Research, under the auspices of the: ‘IN- SPIRES®' Amsterdam, the Netherlands. 4-5 December 2018 * Correspondence: luchomq2077@ gmail.com Abstract 1Intensive Care Unit, Hospital Universitario Sagrado Corazón, The biological effects and physiological consequences of hypercapnia are increasingly Carrer de Viladomat, 288, 08029 understood. The literature on hypercapnia is confusing, and at times contradictory. Barcelona, Spain On the one hand, it may have protective effects through attenuation of pulmonary Full list of author information is available at the end of the article inflammation and oxidative stress. On the other hand, it may also have deleterious effects through inhibition of alveolar wound repair, reabsorption of alveolar fluid, and alveolar cell proliferation. Besides, hypercapnia has meaningful effects on lung physiology such as airway resistance, lung oxygenation, diaphragm function, and pulmonary vascular tree. In acute respiratory distress syndrome, lung-protective ventilation strategies using low tidal volume and low airway pressure are strongly advocated as these have strong potential to improve outcome. These strategies may come at a price of hypercapnia and hypercapnic acidosis. One approach is to accept it (permissive hypercapnia); another approach is to treat it through extracorporeal means. -

Acid-Base Balance

Intensive Care Nursery House Staff Manual Acid-Base Balance INTRODUCTION: The newborn infant is subject to numerous conditions that may disturb acid-base homeostasis. Management of ventilation, which controls the respiratory component of acid-base balance, is discussed in the section on Respiratory Support (P. 10). This section is a brief discussion of the metabolic aspects of acid-base balance. METABOLIC ACIDOSIS, defined as a base deficit >5 mEq/L on the first day and >4 mEq/L thereafter, occurs from: •Loss of buffer (mainly bicarbonate) or •Excess production of acid or decreased excretion of acid The anion gap is a useful calculation in assessing metabolic acidosis. + - - Anion gap = [Na ] – ([Cl ] + [HCO3 ]) Loss of buffer has no effect on anion gap. Accumulation of organic acid (e.g., lactic acid) causes an increase in anion gap. Normal anion gap: <15 mEq/L Increased anion gap: >15 mEq/L in LBW infants (<2,500 g) >18 mEq/L in ELBW infants (<1,000 g) Newborn infants normally have a base deficit of 1 to 3 mEq/L. Common causes of metabolic acidosis: •Bicarbonate loss, especially via immature kidney or from GI tract •Lactic acidosis from inadequate tissue perfusion and oxygenation (e.g., from asphyxia, shock, severe anemia, hypoxemia, PDA, NEC, excessive ventilator pressures with ↓ cardiac output) •Hypothermia •Organic acidemia due to an inborn error of metabolism (see P. 155) •Excessive Cl in IV fluids •Renal failure •Excessive acid load from high protein formula in preterm (late metabolic acidosis of prematurity ) - •Excretion of HCO3 as metabolic compensation for respiratory alkalosis Dilution acidosis is caused by excessive volume expansion (with saline, Ringer’s lactate or dextrose solutions). -

Serum Bicarbonate and Dehydration Severity in Gastroenteritis 71

70 Arch Dis Child 1998;78:70–71 Serum bicarbonate and dehydration severity in Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.78.1.70 on 1 January 1998. Downloaded from gastroenteritis Hassib Narchi Abstract The degree of dehydration was estimated as The concentration of bicarbonate was mild, moderate, or severe by a paediatrician or measured in serum samples from 106 an emergency room doctor (table 1). Concen- children with gastroenteritis and dehy- trations of urea, creatinine, electrolytes, and dration. A concentration less than 22 bicarbonate in serum were measured on a mmol/l was more common in children venous specimen before treatment. A reduced with severe dehydration, but the magni- serum bicarbonate concentration was defined tude of bicarbonate reduction was not sig- as less than 22 mmol/l and an increased anion nificantly diVerent with increasing gap as greater than 16 mmol/l. Blood pH was degrees of dehydration. Doctors should not routinely measured. The glomerular filtra- not rely on the serum bicarbonate concen- tion rate (GFR) was estimated by the formula tration when assessing fluid deficit. devised by Schwartz et al.6 It was defined as (Arch Dis Child 1998;78:70–71) reduced if it fell two standard deviations below the mean for age and sex. The specific gravity Keywords: dehydration; gastroenteritis; serum bicarbo- and pH of urine were measured on the first nate urine sample obtained at presentation. Rehy- dration treatment (by mouth or intravenous) was prescribed at the discretion of the attend- Metabolic acidosis occurs in dehydrated pa- ing doctor. tients with gastroenteritis; there are multiple Statistical analysis of the results was carried causes of this acidosis.1–5 It is generally believed out by the Mann-Whitney test to compare two that acidosis, equated with a reduced concen- means, analysis of variance for more than two tration of bicarbonate in serum, reflects the means, the Kruskal-Wallis one way analysis of severity of dehydration, although no study sub- variance for non-parametric means, and the 2 stantiating this has been found. -

ACS/ASE Medical Student Core Curriculum Acid-Base Balance

ACS/ASE Medical Student Core Curriculum Acid-Base Balance ACID-BASE BALANCE Epidemiology/Pathophysiology Understanding the physiology of acid-base homeostasis is important to the surgeon. The two acid-base buffer systems in the human body are the metabolic system (kidneys) and the respiratory system (lungs). The simultaneous equilibrium reactions that take place to maintain normal acid-base balance are: H" HCO* ↔ H CO ↔ H O l CO g To classify the type of disturbance, a blood gas (preferably arterial) and basic metabolic panel must be obtained. A basic understanding of normal acid-base buffer physiology is required to understand alterations in these labs. The normal pH of human blood is 7.40 (7.35-7.45). This number is tightly regulated by the two buffer systems mentioned above. The lungs contain carbonic anhydrase which is capable of converting carbonic acid to water and CO2. The respiratory response results in an alteration to ventilation which allows acid to be retained or expelled as CO2. Therefore, bradypnea will result in respiratory acidosis while tachypnea will result in respiratory alkalosis. The respiratory buffer system is fast acting, resulting in respiratory compensation within 30 minutes and taking approximately 12 to 24 hours to reach equilibrium. The renal metabolic response results in alterations in bicarbonate excretion. This system is more time consuming and can typically takes at least three to five days to reach equilibrium. Five primary classifications of acid-base imbalance: • Metabolic acidosis • Metabolic alkalosis • Respiratory acidosis • Respiratory alkalosis • Mixed acid-base disturbance It is important to remember that more than one of the above processes can be present in a patient at any given time. -

Toxicity Associated with Carbon Monoxide Louise W

Clin Lab Med 26 (2006) 99–125 Toxicity Associated with Carbon Monoxide Louise W. Kao, MDa,b,*, Kristine A. Nan˜ agas, MDa,b aDepartment of Emergency Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA bMedical Toxicology of Indiana, Indiana Poison Center, Indianapolis, IN, USA Carbon monoxide (CO) has been called a ‘‘great mimicker.’’ The clinical presentations associated with CO toxicity may be diverse and nonspecific, including syncope, new-onset seizure, flu-like illness, headache, and chest pain. Unrecognized CO exposure may lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Even when the diagnosis is certain, appropriate therapy is widely debated. Epidemiology and sources CO is a colorless, odorless, nonirritating gas produced primarily by incomplete combustion of any carbonaceous fossil fuel. CO is the leading cause of poisoning mortality in the United States [1,2] and may be responsible for more than half of all fatal poisonings worldwide [3].An estimated 5000 to 6000 people die in the United States each year as a result of CO exposure [2]. From 1968 to 1998, the Centers for Disease Control reported that non–fire-related CO poisoning caused or contributed to 116,703 deaths, 70.6% of which were due to motor vehicle exhaust and 29% of which were unintentional [4]. Although most accidental deaths are due to house fires and automobile exhaust, consumer products such as indoor heaters and stoves contribute to approximately 180 to 200 annual deaths [5]. Unintentional deaths peak in the winter months, when heating systems are being used and windows are closed [2]. Portions of this article were previously published in Holstege CP, Rusyniak DE: Medical Toxicology. -

Metabolic Acidosis in Childhood: Why, When and How to Treat Acidose Metabólica Na Infância: Por Que, Quando E Como Tratá-La?

0021-7557/07/83-02-Suppl/S11 Jornal de Pediatria Copyright © 2007 by Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria ARTIGO DE REVISÃO Metabolic acidosis in childhood: why, when and how to treat Acidose metabólica na infância: por que, quando e como tratá-la? Olberes V. B. Andrade1, Flávio O. Ihara2, Eduardo J. Troster3 Resumo Abstract Objetivo: Apresentar uma revisão atualizada e crítica sobre os Objectives: To critically discuss the treatment of metabolic acidosis and mecanismos das principais patologias associadaseotratamento da acidose the main mechanisms of disease associated with this disorder; and to metabólica, discutindo aspectos controversos quanto aos benefícios e riscos describe controversial aspects related to the risks and benefits of using da utilização do bicarbonato de sódio e outras formas de terapia. sodium bicarbonate and other therapies. Fontes dos dados: Revisão da literatura publicada, obtida através de Sources: Review of PubMed/MEDLINE, LILACS and Cochrane Library busca eletrônica com as palavras-chave acidose metabólica, acidose láctica, databases for articles published between 1996 and 2006 using the following cetoacidose diabética, ressuscitação cardiopulmonar, bicarbonato de sódio e keywords: metabolic acidosis, lactic acidosis, ketoacidosis, diabetic terapêutica nas bases de dados PubMed/MEDLINE, LILACS e Cochrane ketoacidosis, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, sodium bicarbonate, Library, entre 1996 e 2006, além de publicações clássicas referentes ao treatment. Classical publications concerning the topic were also reviewed. -

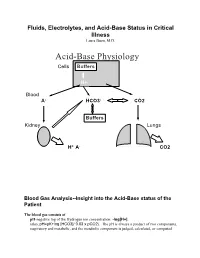

Acid-Base Physiology Cells Buffers

Fluids, Electrolytes, and Acid-Base Status in Critical Illness Laura Ibsen, M.D. Acid-Base Physiology Cells Buffers H+ Blood A- HCO3- CO2 Buffers Kidney Lungs H+ A- CO2 Blood Gas Analysis--Insight into the Acid-Base status of the Patient The blood gas consists of pH-negative log of the Hydrogen ion concentration: -log[H+]. (also, pH=pK+log [HCO3]/ 0.03 x pCO2). The pH is always a product of two components, respiratory and metabolic, and the metabolic component is judged, calculated, or computed by allowing for the effect of the pCO2, ie, any change in the pH unexplained by the pCO2 indicates a metabolic abnormality. - + CO2+H20º H2CO3ºHCO3 + H CO2 and water form carbonic acid or H2CO3, which is in equilibrium with bicarbonate (HCO3-)and hydrogen ions (H+). A change in the concentration of the reactants on either side of the equation affects the subsequent direction of the reaction. For example, an increase in CO2 will result in increased carbonic acid formation (H2CO3) which leads to an increase in both HCO3- and H+ (\pH). Normally, at pH 7.4, a ratio of one part carbonic acid to twenty parts bicarbonate is present in the extracellular fluid [HCO3-/H2CO3]=20. A change in the ratio will affect the pH of the fluid. If both components change (ie, with chronic compensation), the pH may be normal, but the other components will not. pCO2-partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Hypoventilation or hyperventilation (ie, minute ventilation--tidal volume x respitatory rate--imperfectly matched to physiologic demands) will lead to elevation or depression, respectively, in the pCO2.