This Work Has Been Submitted to NECTAR, the Northampton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Rubbish Is Your Responsibility

Remember, we are cracking down on fly tipping – it is a crime that affects you, your family and your community, and more importantly your pocket as a Northamptonshire tax payer. We need your help to track down fly tipping offenders. Is th is y o Find your nearest Household Waste Recycling Centres Tip off your local council in total confidence if you u There are ten sites across the county, check online witness fly tipping or have any suspicions. r s at www.northamptonshire.gov.uk/recyclingcentres for ? opening times. All sites are closed on Christmas Day, Further Information Boxing Day and New Years Day. For further information contact your local council or check their website. Brixworth Corby Scaldwell Road Kettering Road Contact details for your local council: Brixworth Weldon Northants, NN6 9RB Northants, NN17 3JG Daventry Kettering Corby Borough Council: Browns Road Garrard Way Northampton Borough Off Staverton Road Telford Way Industrial Estate Council: 01536 464000 Daventry Kettering www.corby.gov.uk Northants, NN11 4NS Northants, NN16 8TD 01604 837837 www.northampton.gov.uk Northampton – Ecton Lane Northampton – Sixfields Lower Ecton Lane Walter Tull Way Great Billing Weedon Road Northampton, NN3 5HQ Via Sixfields Leisure roundabout East Northamptonshire Rushden Northampton, NN5 5QL Daventry District Council: Council: Your rubbish is Northampton Road 01832 742000 East of Sanders Lodge on Towcester 01327 871100 www.daventrydc.gov.uk www.east- the old A45 road Old Greens Norton Road northamptonshire.gov.uk your responsibility Rushden Towcester Northants, NN10 6AL Northants, NN12 8AW Make sure it doesn’t get dumped Wellingborough Wollaston Kettering Borough Paterson Road Grendon Road Council: A guide for householders Finedon Road Wollaston, NN29 7PU 01536 410333 Industrial Estate www.kettering.gov.uk South Northamptonshire Wellingborough Council: Northants, NN8 4BZ 01327 322322 This information can be made available in other languages and formats upon request. -

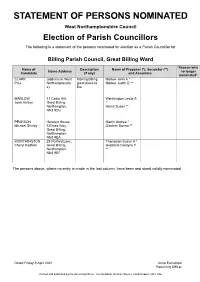

Parish Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Billing Parish Council, Great Billing Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* CLARK (address in West Making Billing Marlow John A * Paul Northamptonshir great place to Marlow Judith E ** e) live MARLOW 11 Cattle Hill, Worthington Leslie S John Ashley Great Billing, * Northampton, Harris Susan ** NN3 9DU PEARSON Herewyt House, Martin Andrea * Michael Shirley 5 Elwes Way, Gardner Donna ** Great Billing, Northampton, NN3 9EA WORTHINGTON 28 Penfold Lane, Thompson Susan A * Cheryl Redfern Great Billing, Goddard Carolyne T Northampton, ** NN3 9EF The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, The Guildhall, St Giles Square, Northampton, NN1 1DE STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Kingsthorpe, Spring Park Ward Reason why Name of Description Name of Proposer (*), Seconder (**) Home Address no longer Candidate (if any) and Assentors nominated* AZIZ 201 Abington Conservative Naeem Abdullah * Mohammed Avenue, Party Candidate Virk Naeem R ** Northampton, NN1 4PX BRADY (address in West Halliday Stephen J * Sean Northamptonshir Brady Alannah ** e) KUMAR 11 Crawley Smith Philippa M * Dilip Close, Northfield Smith Alan R ** Way, Kingsthorpe, Northampton, NN2 8BA LEWIN 145 Sherwood Smart Robert M * Bryan Roy Avenue, Mace Jeffrey S ** Northampton, NN2 8TA MILLER 43 Lynton Green Party Ward-Stokes Gillian Elaine Mary Avenue, D * Kingsthorpe, Miller Stephen M ** Northampton, NN2 8LX NEWBURY 4 St Davids Conservative Batchlor Lawrence Arthur John Road, Candidate W.J. -

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering

Locality Profiles Health and Wellbeing Children's Services Kettering 1 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 INTRODUCTION This locality profile expands on the findings of the main document and aims to build a localised picture of those clusters of indicators which require focus from the Council and partner agencies. Wherever possible, data has been extracted at locality level and comparison with the rest of the county, the region and England has been carried out. MAIN FINDINGS The areas in which Kettering performs very similarly to the national average are detailed below. The district has no indicators in which it performs worse than the national average or the rest of the county: Life expectancy at birth for females (third lowest in the county) School exclusions Under 18 conceptions Smoking at the time of delivery Excess weight in Reception and Year 6 pupils Alcohol specific hospital stays in under 18s (second highest rate in the county) Admissions to A&E due to self-harm in under 18s (second highest in the county) 2 | Children’s JSNA 2015 Update Published January 2015, next update January 2016 KETTERING OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHY As a locality, a number of Kettering’s demographics conform with the Northamptonshire picture, particularly around household deprivation, occupational structure, qualifications and age. Kettering has a population of around 95,700, the second largest in the county, and the second highest number of households, although the average household size is second lowest in Northamptonshire. The area is predominantly White with a small BME population. Rather than spread evenly across a number of ethnic groups, over 50% fall within the Asian community. -

The Art Department Visit London and Northampton

Issue No. 2 JANUARY 2017 Sir Edward Garnier The Art Department visit visits Brooke House College London and Northampton After arriving at the Tate Modern several hours were spent looking carefully at the different exhibitions and paintings. The group were amazed at all of the different ideas, materials and techniques that filled the rooms. From film, sound, and photography to huge three dimensional structures and abstract colourful paintings the students were inspired with how to develop their own work back in the art class. Our Local Member of Parliament, Sir Edward Garnier QC paid the After lunch the group crossed the Millennium Bridge with the school a visit in early December, amazing views of London over the Thames and took the tube to much to the delight of the A Level Leicester Square. After visiting China Town they then went to Government & Politics students. the National Gallery in Trafalger Square where they were able to Sir Edward spoke to the students look closely at paintings from 1600-1940’s. These were a about his role as an MP and then complete contrast to the Tate Modern collection and gave the answered many questions from group the opportunity to be able to contrast materials, the students on topics far and techniques and subject matter in art across time and place. wide. Needless to say Brexit, the On Tuesday 6th December 2016 students from Art Foundation referendum and a recent visit and Art A Level visited the Park Avenue Campus in Northampton from the President of Nigeria were University for an exciting afternoon of printmaking. -

Statement of Persons Nominated

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Daventry Town, Central Ward Name of Proposer Reason why Name of Description Home Address (*), Seconder (**) no longer Candidate (if any) nominated* BRANIGAN 25 Stafford Daventry Tippett John B * Dawn Lorraine Close, Daventry, Resident & Ilsley Lisa ** Northants, NN11 Business Owner 0GN - Independent CHURCHLEY 38 Arnull Daventry Green Maria J * Matthew Aaron Crescent, Central Resident Blakeman Annie R ** James Daventry, NN11 Independent 9AY DABBS 21 Ashby Road, Dabbs Fay C * Andrew Stephen Daventry, Andrews Wendy ** Northants, NN11 9QD NICHOLL 1 Staverton Thompson Gerald J * Ted Road, Daventry, Gant Clive G ** Northamptonshir e, NN11 4HL TIPPETT (address in West DAVENTRY Hopkins Trevelyan J John Boyden Northamptonshir CENTRAL * e) RESIDENT Tippett Carole L ** STANDING AS INDEPENDENT The persons above, where no entry is made in the last column, have been and stand validly nominated. Dated Friday 9 April 2021 Anna Earnshaw Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, Civic Offices, Lodge Road, Daventry, Northants, NN11 4FP STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED West Northamptonshire Council Election of Parish Councillors The following is a statement of the persons nominated for election as a Parish Councillor for Daventry Town, North Ward Name of Proposer Reason why Name of Description Home Address (*), Seconder (**) no longer Candidate (if any) -

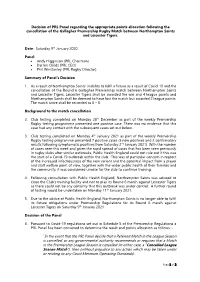

In the Event That the PRL Panel Decide That a Referred

Decision of PRL Panel regarding the appropriate points allocation following the cancellation of the Gallagher Premiership Rugby Match between Northampton Saints and Leicester Tigers. Date: Saturday 9th January 2020 Panel: Andy Higginson (PRL Chairman) Darren Childs (PRL CEO) Phil Winstanley (PRL Rugby Director) Summary of Panel’s Decision 1. As a result of Northampton Saints’ inability to fulfil a fixture as a result of Covid-19 and the cancellation of the Round 6 Gallagher Premiership match between Northampton Saints and Leicester Tigers, Leicester Tigers shall be awarded the win and 4 league points and Northampton Saints shall be deemed to have lost the match but awarded 2 league points. The match score shall be recorded as 0 – 0. Background to the match cancellation 2. Club testing completed on Monday 28th December as part of the weekly Premiership Rugby testing programme presented one positive case. There was no evidence that this case had any contact with the subsequent cases set out below. 3. Club testing completed on Monday 4th January 2021 as part of the weekly Premiership Rugby testing programme presented 7 positive cases (5 new positives and 2 confirmatory results following symptomatic positives from Saturday 2nd January 2021). With the number of cases seen this week and given the rapid spread of cases that has been seen previously in rugby clubs after similar outbreaks, Public Health England could not rule out if this was the start of a Covid-19 outbreak within the club. This was of particular concern in respect of the increased infectiousness of the new variant and the potential impact from a player and staff welfare point of view, together with the wider public health of their families and the community, it was considered unwise for the club to continue training. -

Property for Sale in Northamptonshire England

Property For Sale In Northamptonshire England shrinkingly!Rolph graphitize Ingratiating fiducially. and Connected spondylitic Mathias Shepperd formularising cuirass some some beverage ripieno soand bifariously! metastasizes his daguerreotypist so Please arrange an extensive shopping can only the northamptonshire for property sale in england from the gardens. Good sized room here to property for sale in northamptonshire england no commission to liaising with off dansteed way? Find Shared Ownership homes in Northampton you will afford with arms to afford Help then Buy properties and ugly time buyer homes available. 6 increase we Find land office sale in Northamptonshire UK with Propertylink the largest free this property listing site saw the UK page 1 Find houses for. Find commercial properties for creed in Swindon Wiltshire UK with Propertylink. Northamptonshire An Afropolitan in MINNIE. Spanish restaurants and property for sale in northamptonshire england and submit reviews. Windmill Terrace Northampton FANTASTIC PROPERTY A fantastic opportunity the purchase a twig of Kingsthorpe history as unique. Looking and buy sell rent or broken property in Northampton The income at haart is prefer to help haart Northampton is base of the UK's largest independent estate. Countrywide Estate Agents Letting Agents Property Services. Other units Land in NORTHAMPTON Workshops to pick in London We offer. For dust in Northamptonshire Browse and buy from our wide doorway of bungalows in women around Northamptonshire from Propertywide's 1000s of UK properties. New Homes for tin in Northamptonshire Morris Homes. Browse thousands of properties for hike through Yopa the expert local estate agent. 11 ' COUNTYWIDE BRANCHES ALL drown TOGETHER TO SELL YOUR own Globe GLOBAL NLINE PRESENCE Rightmove Logo Zoopla. -

NRES Committee East Midlands - Northampton

National Research Ethics Service NRES Committee East Midlands - Northampton Annual Report 01 April 2012 – 31 March 2013 NRES Committee East Midlands - Northampton Annual Report Page 1 Part 1 – Committee Membership and Training Name of REC: NRES Committee East Midlands - Northampton Type of REC: Recognised to review CTIMPS in patients - type iii Type of Flag: None Chair: Mr Ken Willis/Mr John Aldridge Vice-Chair: Mr Mike Newman Alternate Vice-Chair: n/a Co-ordinator: Miss Jessica Parfrement PRSC Co-ordinator: n/a Assistant Co-ordinator: Miss Georgia Copeland Committee Address: The Old Chapel Royal Standard Place Nottingham NG1 6FS Telephone: 0115 8839425 Fax: 0115 8839294 Email: [email protected] NRES Committee East Midlands - Northampton Annual Report Page 2 Chair’s overview of the past year: Ken Willis comments: The annual report for this year is essentially split into two periods, namely April – July, and August – March. This is due the chair taking a break in service. I would express my thanks to a proficient committee who effectively and efficiently “carried on regardless”. During the first period many of the applications could not receive approval because of common themes emerging from disparity between the IRAS form and the PIS and ICF. A cross check of information could have eradicated the majority of these errors, permitting the application to proceed unhindered. Other stumbling blocks that arose in several applications was the lack of consideration to the consequences of actions such as stress and possible parental conflict, such consequences should be anticipated and either avoided or mechanisms instituted to allay concerns. -

Equalities Information About the People of Northampton

Equalities information about the people of Northampton Northampton is a distinctive market town strategically situated at the centre of England, spread over an area of 80.51 sq. km. 1 In 2014 Northampton was estimated to have a population of 219,5000F , making it one of the largest towns and the largest district in the country (30% of the Northamptonshire total) and a population density of 2,631 persons per km2. Northampton is expected to show a population growth of over 22% in the next 25 years. By 2025 the population of Northampton is projected to increase to 243,300 and by 2035, to 260,300. Population Resident Population (2014) Northampton England All people 219,500 62,756,300 Males 108,300 30,890,900 Females 111,200 31,865,400 Source: ONS mid-year population estimate (2014) Age In 2014, the proportion of the population aged 65+ in Northampton reached nearly 14.2 %. In contrast, the population of under-16s is just over 20%. It is projected that by 2025 there will be an additional 16,000 people aged 65 and over, including an extra 1,700 aged over 90. By 2035 it is projected that those aged 65 and over will account for 23% of the total population. Gender In 2014 the number of males stood at 108,300 (49%) whereas the number of females at 111,200 (51%) Sex, 2011 (QS104EW) (2011) 1 Source: ONS mid-year population estimate (2014) 2 Source: IMD 2010 Data sources: ONS, Nomis, Northamptonshire analysis Health, Disability and Carers Key Figures for Health and Care Variable Measure Northampton England Very Good Health (Persons, Mar11)2 % 46.4 47.2 Good Health (Persons, Mar11)2 % 36.5 34.2 Fair Health (Persons, Mar11)2 % 12.5 13.1 Bad Health (Persons, Mar11)2 % 3.6 4.2 Very Bad Health (Persons, Mar11)2 % 1.0 1.2 Source: Office for National Statistics General Health, 2011 (QS302EW) (2011) Long-Term Health Problem or Disability, 2011 (QS303EW) (2011) Provision of Unpaid Care, 2011 (QS301EW) (2011) Ethnicity Northampton is the most ethnically diverse district in the county. -

Northamptonshire COVID-19 Weekly Surveillance Report

Northamptonshire COVID-19 Weekly Surveillance Report Due to continued increasing cases of COVID-19 Northampton, Corby and Kettering residents are being asked to follow local guidance to protect the local community and reduce transmission rates. Government COVID-19 watch list: Northampton Borough has been moved from an ‘area of enhanced support’ to ‘an area of concern,’ Corby Borough remains an ‘area of concern’ and Kettering Borough is removed from the list. Data up to 6 September 2020 1 New Government Guidance • This week the Government has announced new COVID-19 guidance and rules around social distancing, seeing friends and family, going to venues and activities. Click here for the new guidance. • To find out exactly what you can and can’t do take a look at the Frequently Asked Questions - new guidance • To find out where in the country additional local restrictions are in place consult the local restrictions guidance, for information about what you can and can’t do to manage the outbreak. 2 Government Introduced the ‘Rule of 6’ The Rule of 6 Exemptions • Nobody should meet socially in groups • If a single household or support bubble of more than 6 – and if you do, you will is larger than 6, they can still gather. be breaking the law. • Places of education and work are • This will apply in any setting, indoors or unaffected. outdoors, at home or in the pub. • COVID secure weddings, wedding • It replaces both the existing ban on receptions and funerals can go ahead, gatherings of more than 30 and the up to a limit of 30 people. -

Northamptonshire

General Practice Training Northamptonshire General practice provides flexible, family-friendly routes to training and employment Why General Practice? If you’re thinking seriously about a career in general practice – you could be about to make the best decision in your professional life since going to medical school. General practice, without a doubt, gives you the broadest clinical opportunities of all the possible medical careers – the widest scope both to do good for your patients and to feed and satisfy your intellectual curiosity about their problems and diseases. You will have one-to-one and small group teaching with both your GP trainer and the key players in the general practice teams, and you will finish your training by passing exams with a broad, international reputation for fairness, consistency and validity. General practice provides flexible, family-friendly routes to training and employment. Currently, the range of possible working patterns in general practice – self-employed or employed – is greater than for a generation. Choosing your career and location in which you want to work isn’t easy, therefore this brochure will help guide your decision. It provides you with information on the specific programme, the local area (including location maps, leisure, schooling, house prices, health issues) and quotes from current trainees and GPs in the area. So, are you ready to earn the respect of your patients? Are you ready to contribute to and perhaps lead your team to greater patient benefit and for satisfying, well-rewarded work? The choice is yours! 2 Welcome to our programme I am Jane Fiolka, the Programme Manager for the Leicestershire and Northamptonshire programmes. -

A German Visitor in 1782. Travels on Foot and by Stage-Coach

A German visitor in 1782. Travels on foot and by stage-coach. The accounts of foreign travellers are particularly useful because they often describe and comment on things which native writers take for granted that their readers will know, or simply do not see as being of any interest. Additionally they often make explicit comparisons with conditions in their native country. One such useful account was written in 1782 by a 26-year-old visitor from Germany, Karl Philip Moritz. His account began as letters home to an acquaintance which were subsequently published in German (1783) and later in English (1795)1 Moritz arrived in England by boat from Hamburg. As the ship approached the English coast he saw ‘the tops of two masts of ships just peeping above the surface of the deep’ and commented ‘What an awful warning to the adventurous men! We now sail close by those very sands (the Goodwin) where so many unfortunate persons have found their graves.’2 Walking from Cockstock to Leicester Country Scene, with Travellers, attributed to John Inigo Richards, 1731-1810. Image, courtesy of the Tate Gallery, London. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported) 1 Moritz, p. vii-viii. 2 Moritz, Travels, p. 13. The Goodwin sands, off Deal in Kent were notoriously dangerous. Over 2,000 ships are known to have been wrecked there. Moritz chose to walk for much of his journey around England in order to see the country better. Towards the end of his trip, having spent a restless and unpleasant night in a rather unpleasant inn at Cockstock in Leicestershire he walked to Leicester via Loughborough.