Seal Distemper Outbreak 2002 Tom Barrett, Pramoda Sahoo & Paul D. Jepson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Risk of Disease Spillover from Dogs to Wild Carnivores in Kanha Tiger Reserve, India. Running Head

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/360271; this version posted July 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Title: Risk of disease spillover from dogs to wild carnivores in Kanha Tiger Reserve, India. Running head: Disease spillover from dogs to carnivores V. Chaudhary1,3 *, N. Rajput2, A. B. Shrivastav2 & D. W. Tonkyn1,4 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, SC, 29634, USA 2 School of Wildlife Forensic and Health, South Civil Lines, Jabalpur, M. P., India 3 Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32603, USA 4 Department of Biology, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Little Rock, AR 72204, USA Key words Canine Distemper Virus, Canine Parvovirus, Canine Adeno Virus, Rabies, Tiger, Dog, India, Wildlife disease Correspondence * V. Chaudhary, Newins-Ziegler Hall,1745 McCarty Road, Department of Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, 32611. Email: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/360271; this version posted July 3, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abstract Many mammalian carnivore species have been reduced to small, isolated populations by habitat destruction, fragmentation, poaching, and human conflict. -

Canine Distemper Virus in Asiatic Lions of Gujarat State, India

RESEARCH LETTERS SFTSV RNA at 2.4 × 105 copies/mL in his semen that day. Canine Distemper Virus On day 44, we could no longer detect semen SFTSV RNA, and he was discharged on day 51 after onset (Figure 1). in Asiatic Lions of In this study, SFTSV RNA was detected in semen, and Gujarat State, India SFTSV persisted longer in semen than in serum. It is well known that some viruses, such as Zika virus and Ebola vi- rus, can be sexually transmitted; these viruses have been Devendra T. Mourya, Pragya D. Yadav, detected in semen for a prolonged period after symptom Sreelekshmy Mohandas, R.F. Kadiwar, M.K. Vala, onset (6,7). Thus, we considered the potential risk for sex- Akshay K. Saxena, Anita Shete-Aich, ual transmission of SFTSV. Nivedita Gupta, P. Purushothama, Rima R. Sahay, Compared with that of Zika and Ebola viruses, the clin- Raman R. Gangakhedkar, Shri C.K. Mishra, ical significance of potential sexual transmission of SFTSV Balram Bhargava is unknown. However, this possibility should be taken into Author affiliations: Indian Council of Medical Research, National consideration in sexually active patients with SFTSV. Our Institute of Virology, Pune, India (D.T. Mourya, P.D. Yadav, findings suggest the need for further studies of the genital S. Mohandas, A. Shete-Aich, R.R. Sahay); Sakkarbaug Zoo, fluid of SFTS patients, women as well as men, and counsel- Junagadh, India (R.F. Kadiwar, M.K. Vala); Department of ing regarding sexual behavior for these patients. Principal Chief Conservator of Forest, Gandhinagar (A.K. Saxena, P. -

Phylogenetic Characterization of Canine Distemper Viruses Detected in Naturally Infected North American Dogs

PHYLOGENETIC CHARACTERIZATION OF CANINE DISTEMPER VIRUSES DETECTED IN NATURALLY INFECTED NORTH AMERICAN DOGS __________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia _________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science __________________________________________________ by INGRID D. R. PARDO Dr. Steven B. Kleiboeker, Thesis Supervisor May 2006 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Steven B. Kleiboeker, for this teaching, support and patience during the time I spent in the Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory and Department of Veterinary Pathobiology at the University of Missouri-Columbia. I also extend appreciation to my committee members: Drs. Gayle Johnson, Cynthia Besch-Williford, and Joan Coates for their academic support over the past three years, with a special thanks to Dr. Joan Coates for her extensive guidance during the preparation of this thesis. Additionally, I will like to express my gratitude to Dr. Susan K. Schommer, Mr. Jeff Peters, Ms. Sunny Younger, and Ms. Marilyn Beissenhertz for laboratory and technical support. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEGEMENTS……………………………………………………………. ii LIST OF FIGURES ………………………………………………………………….. v LIST OF TABLES……………………………………………………………………. vi ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………... vii I. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………. 1 A. Etiology ……………………………...…………………………………….. 1 B. Epidemiology -

Canine Distemper Virus (CDV) Also Causes Gastrointestinal Illness, Thickening of the Nose and Foot Pads, and a NEUROLOGIC Phase That Has Symptoms Similar to RABIES

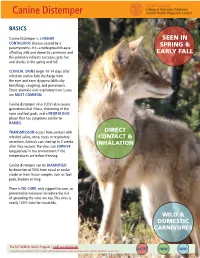

Canine Distemper BASICS Canine Distemper is a HIGHLY SEEN IN CONTAGIOUS disease caused by a SPRING & paramyxovirus. It is a widespread disease affecting wild and domestic carnivores and EARLY FALL this primarily infeects raccoons, grey fox and skunks in the spring and fall. CLINICAL SIGNS begin 10-14 days after infection and include discharge from the eyes and nose, dyspnea (difficulty breathing), coughing, and pneumonia. Fever, anorexia and respiratory tract issues are MOST COMMON. Canine distemper virus (CDV) also causes gastrointestinal illness, thickening of the nose and foot pads, and a NEUROLOGIC phase that has symptoms similar to RABIES. TRANSMISSION occurs from contact with DIRECT infected saliva, urine, feces or respiratory CONTACT & secretions. Animals can shed up to 2 weeks INHALATION after they recover. The virus can SURVIVE long periods in the environment if the temperatures are below freezing. Canine distemper can be DIAGNOSED by detection of DNA from nasal or ocular swabs or from tissue samples such as foot pads, bladder or lung. There is NO CURE, only supportive care, so preventative measures to reduce the risk of spreading the virus are key. This virus is nearly 100% fatal for mustelids. WILD & DOMESTIC CARNIVORES The NYS Wildlife Health Program | cwhl.vet.cornell.edu ALERT HOW WHO A partnership between NYS Dept. of Environmental Conservation and Cornell Wildlife Health Lab DETAILS The NEUROLOGIC PHASE of the disease affects the The disease is found in canids (domestic dogs, coyotes, central nervous system and can cause disorientation wolves, foxes) as well as raccoons, javelinas, and some and weakness along with progressive seizures. -

Canine Distemper Closely CANINE Resembles Rabies

leading to its nickname “hard pad disease.” For more information, visit: In wildlife, infection with canine distemper closely CANINE resembles rabies. www.avma.org Distemper is often fatal, and dogs that survive usually have permanent, irreparable nervous system damage. DISTEMPER Brought to you by your veterinarian and the American Veterinary Medical Association HOW IS CANINE DISTEMPER DIAGNOSED AND TREATED? Veterinarians diagnose canine distemper through clinical appearance and laboratory testing. There is no cure for canine distemper infection. Treatment typically consists of supportive care and efforts to prevent secondary infections, control vomiting, diarrhea and neurologic symptoms, and combat dehydration through administration of fluids. Dogs infected with canine distemper should be separated from other dogs to minimize the risk of further infection. HOW IS CANINE DISTEMPER PREVENTED? Vaccination is crucial in preventing canine distemper. • A series of vaccinations is administered to puppies to increase the likelihood of building immunity when the immune system has not yet fully matured. • Avoid gaps in the immunization schedule and make sure distemper vaccinations are up to date. • Avoid contact with infected animals and wildlife • Use caution when socializing puppies or unvaccinated dogs at parks, puppy classes, obedience classes, doggy day care and other places where dogs can congregate. • Pet ferrets should be vaccinated against canine distemper using a USDA-approved ferret vaccine. www.avma.org | 800.248.2862 CANINE DISTEMPER is a contagious disease caused by a virus that attacks the respiratory, gastrointestinal and nervous systems of puppies and dogs. The virus can also be found in wildlife such as foxes, wolves, coyotes, raccoons, skunks, mink and ferrets and has been reported in lions, tigers, leopards and other wild cats as well as seals. -

Canine Distemper Outbreak by Natural Infection in a Group of Vaccinated Maned Wolves in Captivity

pathogens Article Canine Distemper Outbreak by Natural Infection in a Group of Vaccinated Maned Wolves in Captivity Vicente Vergara-Wilson 1,†, Ezequiel Hidalgo-Hermoso 1,2,*,†, Carlos R. Sanchez 3, María J. Abarca 4, Carlos Navarro 4, Sebastian Celis-Diez 2, Pilar Soto-Guerrero 2, Nataly Diaz-Ayala 1, Martin Zordan 1,5, Federico Cifuentes-Ramos 4 and Javier Cabello-Stom 6 1 Conservation and Research Department, Parque Zoologico Buin Zoo, Panamericana Sur Km 32, Buin 9500000, Chile; [email protected] (V.V.-W.); [email protected] (N.D.-A.); [email protected] (M.Z.) 2 Departamento de Veterinaria, Parque Zoologico Buin Zoo, Panamericana Sur Km 32, Buin 9500000, Chile; [email protected] (S.C.-D.); [email protected] (P.S.-G.) 3 Living Collection Unit, Veterinary Medical Center, Oregon Zoo, Portland, OR 97221, USA; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, University of Chile, Av. Santa Rosa, Santiago 11735, Chile; [email protected] (M.J.A.); [email protected] (C.N.); [email protected] (F.C.-R.) 5 World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), Carrer de Roger de Llúria, 2, 2-208010 Barcelona, Spain 6 Patagonia Campus, School of Veterinary Medicine, Universidad San Sebastian, Puerto Montt 5480000, Chile; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors have joint credit as first author. Abstract: Canine distemper virus (CDV) is one of the most significant infectious disease threats to the health and conservation of free-ranging and captive wild carnivores. CDV vaccination using recombinant canarypox-based vaccines has been recommended for maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus) Citation: Vergara-Wilson, V.; after the failure of modified live vaccines that induced disease in vaccinated animals. -

Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex (CIRDC) Information for Dog Owners

Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex (CIRDC) Information for Dog Owners Key Facts Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex (CIRDC) is very common and can be due to one or more bacterial and viral organisms. Signs of disease can be: • Mild, e.g. cough, sneeze, discharge from the eyes or nose, fever • Progressive, i.e. begin as mild signs that rapidly worsen • Severe, such as pneumonia complicated with bacterial infection In most dogs, signs of disease are mild and self-limiting (i.e. resolve on their own) in 7-10 days. Outbreaks can occur as disease spreads rapidly from dog-to-dog. This is a particular concern for dogs in group settings (e.g. dog shows, boarding, doggie daycare, dog parks), which have high dog-to-dog contact. Vaccines that lessen disease severity and reduce organism shedding are available for some of the infectious bacteria and viruses involved in CIRDC. What is it? Canine Infectious Respiratory Disease Complex In most dogs, signs of disease are self-limiting (CIRDC), sometimes referred to as ‘kennel cough’ (i.e. resolve on their own) in 7-10 days with or ‘canine cough,’ is a clinical syndrome. At least nursing care, e.g. cough suppressant. nine different bacteria and viruses have been linked as causes of CIRDC. Co-infections (i.e. infection with more than one bacterial or viral agent) are common. Common viral causes of CIRDC include canine adenovirus 2, canine distemper virus, canine influenza viruses, canine herpesvirus, and canine parainfluenza virus (see Resources for links to individual factsheets). Common bacterial causes of CIRDC include Bordetella bronchiseptica, Streptococcus equi subspecies zooepidemicus, and Mycoplasma spp. -

LARGE CANID (Canidae) CARE MANUAL

LARGE CANID (Canidae) CARE MANUAL CREATED BY THE AZA Canid Taxon Advisory Group IN ASSOCIATION WITH THE AZA Animal Welfare Committee Large Canid (Canidae) Care Manual Large Canid (Canidae) Care Manual Published by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums in association with the AZA Animal Welfare Committee Formal Citation: AZA Canid TAG 2012. Large Canid (Canidae) Care Manual. Association of Zoos and Aquariums, Silver Spring, MD. p.138. Authors and Significant contributors: Melissa Rodden, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, AZA Maned Wolf SSP Coordinator. Peter Siminski, The Living Desert, AZA Mexican Wolf SSP Coordinator. Will Waddell, Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium, AZA Red Wolf SSP Coordinator. Michael Quick, Sedgwick County Zoo, AZA African Wild Dog SSP Coordinator. Reviewers: Melissa Rodden, Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, AZA Maned Wolf SSP Coordinator. Peter Siminski, The Living Desert, AZA Mexican Wolf SSP Coordinator. Will Waddell, Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium, AZA Red Wolf SSP Coordinator. Michael Quick, Sedgwick County Zoo, AZA African Wild Dog SSP Coordinator. Mike Maslanka, Smithsonian’s National Zoo, AZA Nutrition Advisory Group Barbara Henry, Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden, AZA Nutrition Advisory Group Raymond Van Der Meer, DierenPark Amersfoort, EAZA Canid TAG Chair. Dr. Michael B. Briggs, DVM, MS, African Predator Conservation Research Organization, CEO/Principle Investigator. AZA Staff Editors: Katie Zdilla, B.A. AZA Conservation and Science Intern Elisa Caballero, B.A. AZA Conservation and Science Intern Candice Dorsey, Ph.D. AZA Director, Animal Conservation Large Canid Care Manual project consultant: Joseph C.E. Barber, Ph.D. Cover Photo Credits: Brad McPhee, red wolf Bert Buxbaum, African wild dog and Mexican gray wolf Lisa Ware, maned wolf Disclaimer: This manual presents a compilation of knowledge provided by recognized animal experts based on the current science, practice, and technology of animal management. -

Phylogenetic Evidence of a Novel Lineage of Canine Pneumovirus And

Piewbang and Techangamsuwan BMC Veterinary Research (2019) 15:300 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-019-2035-1 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Phylogenetic evidence of a novel lineage of canine pneumovirus and a naturally recombinant strain isolated from dogs with respiratory illness in Thailand Chutchai Piewbang1 and Somporn Techangamsuwan1,2* Abstract Background: Canine pneumovirus (CPV) is a pathogen that causes respiratory disease in dogs, and recent outbreaks in shelters in America and Europe have been reported. However, based on published data and documents, the identification of CPV and its variant in clinically symptomatic individual dogs in Thailand through Asia is limited. Therefore, the aims of this study were to determine the emergence of CPV and to consequently establish the genetic characterization and phylogenetic analysis of the CPV strains from 209 dogs showing respiratory distress in Thailand. Results: This study identified and described the full-length CPV genome from three strains, designated herein as CPV_ CP13 TH/2015, CPV_CP82 TH/2016 and CPV_SR1 TH/2016, that were isolated from six dogs out of 209 dogs (2.9%) with respiratory illness in Thailand. Phylogenetic analysis suggested that these three Thai CPV strains (CPV TH strains) belong to the CPV subgroup A and form a novel lineage; proposed as the Asian prototype. Specific mutations in the deduced amino acids of these CPV TH strains were found in the G/glycoprotein sequence, suggesting potential substitution sites for subtype classification. Results of intragenic recombination analysis revealed that CPV_CP82 TH/2016 is a recombinant strain, where the recombination event occurred in the L gene with the Italian prototype CPV Bari/100–12 as the putative major parent. -

Population Dynamics and Disease in Endangered African Wild Dogs Elizabeth Claire Arredondo University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2018 Defending Wild Dogs: Population Dynamics and Disease in Endangered African Wild Dogs Elizabeth Claire Arredondo University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Animal Diseases Commons, Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons, and the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Arredondo, Elizabeth Claire, "Defending Wild Dogs: Population Dynamics and Disease in Endangered African Wild Dogs" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 2823. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2823 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Defending Wild Dogs: Population Dynamics and Disease in Endangered African Wild Dogs A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biology by Elizabeth Arredondo University of Arkansas Bachelor of Science in Biology, 2011 May 2018 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation by the Graduate Council ____________________________________ Steven Beaupre, PhD Thesis Director ___________________________________ ___________________________________ J.D. Willson PhD Adam Siepielski, PhD Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) are endangered carnivores whose population is decreasing from habitat loss and fragmentation, interspecific competition, and disease. Survival rates are especially low in Kruger National Park (KNP), though it is unclear why. I estimated the abundance in KNP and survival rates over different time spans, six years and nine months, using public photographic survey data. -

Canine Vaccination Recommendations

Lindsey Hanson, D.V.M. 7140 S. 29th St. Lincoln, NE 68516 Phone: 402-421-2300 Fax: 402-421-2319 Email: [email protected] Website: southridgeanimalclinic.com Canine Vaccination Recommendations According to the American Animal Hospital Association vaccination guidelines, the following vaccines are considered “core” (essential) vaccines for all dogs in the United States: • RaBies virus • Canine distemper • Canine parvovirus • Canine adenovirus • Canine parainfluenza virus RaBies RaBies is a 100% fatal disease of mammals. Because there is no effective treatment and the disease can also infect humans, vaccination against the raBies virus is required By law in most states. Typically, the raBies vaccine is administered to pets in a separate injection at the same time as the canine distemper comBination vaccine. However, the raBies vaccine can also Be given alone (at a separate visit) or at the same time as other vaccines (such as the Lyme disease vaccine). RaBies is considered to Be a core vaccine for dogs. Canine Distemper ComBination While commonly called canine distemper vaccination, this vaccine typically protects your pet against more than just distemper. It is actually a comBination of vaccines in one injection that will protect your pet from several serious diseases that are highly contagious and associated with a high death rate. The exact comBination of your dog’s distemper comBination vaccine depends on your dog’s age and individual disease-risk profile. In general, the most important diseases to protect against are canine distemper, canine adenovirus-2 infection (hepatitis and respiratory disease), canine parvovirus infection, and parainfluenza. The aBBreviation for this comBination vaccine is frequently written as “DHPPV,” “DHPP,” “DAPP,” or “DA2PPV” on your pet’s health records. -

Information About Camera Trap Records of Dholes in Thailand

Jenks et al. Camera trap records of dholes in Thailand Copyright © 2012 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Field Report Camera trap records of dholes in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand Kate E. Jenks*1,2, Nucharin Songsasen2 and Peter Leimgruber2 1 Graduate Programs in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, and Wildlife and Fisheries Conservation, University of Massachusetts, 611 N. Pleasant Street, Amherst, MA 01003, USA . Email: [email protected] 2 Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, 1500 Remount Road, Front Royal, VA 22630, USA. * Correspondence author Keywords: Asian wild dog, Cuon alpinus, distribution, zero-inflation Poisson regression model Abstract In response to a lack of data on dholes Cuon alpinus, we initiated an intensive field study of dholes in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary (KARN) in eastern Thailand to gather critical baseline information on the factors influencing dhole presence. Dholes have declined over time, are exposed to continued pressure from humans, yet are taking over the role of top-predator in many Thai protected areas with the extirpa- tion of tigers Panthera tigris. During January 2008-February 2010, we obtained 67 independent photo- graphs (n = 4,505 camera-trap nights) of dholes along with photos of 27 mammal species in KARN. To evaluate factors determining dhole presence we used a zero-inflation Posisson regression model. We did not detect any significant influence of human activity on dhole presence. However, our photos confirmed that dholes and domestic dogs use overlapping areas at KARN. The presence of domestic dogs could have implications for competition or disease spillover.