Carpenter Ecu 0600M 10604.Pdf (482.9Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

You Stay Here

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Michael A. Bluhm for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Creative Writing presented on June 2. 2003. Title: You Stay Here Abstract Approved: Redacted for privacy Tracy Daugherty You Stay Here isthe beginning of a novel that centers on the notion of family, community, and the expectations that drive our interactions within these circles. The novel tells the story of brothers Mills and Nance O'Malley as they interact with their parents, Richard and Margaret. The brothers own a landscaping business which they run from the family garage while living in the basement of their childhood home. Set in fictional Hatfield, Wisconsin, YouStqy Herestrives to uncover the intricacies of brotherhood amid crises, the role work plays in healing, and what happens when we try to escape our circumstances. © Copyright by Michael A. Bluhm June 2, 2003 All Rights Reserved You Stay Here by Michael A. Bluhm A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts Presented June 2, 2003 Commencement June 2004 Master of Fine Arts thesis of Michael A. Bluhm presented on June 2. 2003. APPROVED: Redacted for privacy Major Professlr, rept'sentingtreative Writing Redacted for privacy ('hair of Department of English Redacted for privacy uate School I understand that my thesis wifi become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. My signature below authorizes release of my thesis to any reader upon request. Redacted for privacy Michael A. Bluhm, Author ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I cannot overstate my appreciation for the time, effort and skillith which Tracy Daugherty continually read my work and met with me to discuss this business of writing. -

Song List 2012

SONG LIST 2012 www.ultimamusic.com.au [email protected] (03) 9942 8391 / 1800 985 892 Ultima Music SONG LIST Contents Genre | Page 2012…………3-7 2011…………8-15 2010…………16-25 2000’s…………26-94 1990’s…………95-114 1980’s…………115-132 1970’s…………133-149 1960’s…………150-160 1950’s…………161-163 House, Dance & Electro…………164-172 Background Music…………173 2 Ultima Music Song List – 2012 Artist Title 360 ft. Gossling Boys Like You □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Avicii Remix) □ Adele Rolling In The Deep (Dan Clare Club Mix) □ Afrojack Lionheart (Delicious Layzas Moombahton) □ Akon Angel □ Alyssa Reid ft. Jump Smokers Alone Again □ Avicii Levels (Skrillex Remix) □ Azealia Banks 212 □ Bassnectar Timestretch □ Beatgrinder feat. Udachi & Short Stories Stumble □ Benny Benassi & Pitbull ft. Alex Saidac Put It On Me (Original mix) □ Big Chocolate American Head □ Big Chocolate B--ches On My Money □ Big Chocolate Eye This Way (Electro) □ Big Chocolate Next Level Sh-- □ Big Chocolate Praise 2011 □ Big Chocolate Stuck Up F--k Up □ Big Chocolate This Is Friday □ Big Sean ft. Nicki Minaj Dance Ass (Remix) □ Bob Sinclair ft. Pitbull, Dragonfly & Fatman Scoop Rock the Boat □ Bruno Mars Count On Me □ Bruno Mars Our First Time □ Bruno Mars ft. Cee Lo Green & B.O.B The Other Side □ Bruno Mars Turn Around □ Calvin Harris ft. Ne-Yo Let's Go □ Carly Rae Jepsen Call Me Maybe □ Chasing Shadows Ill □ Chris Brown Turn Up The Music □ Clinton Sparks Sucks To Be You (Disco Fries Remix Dirty) □ Cody Simpson ft. Flo Rida iYiYi □ Cover Drive Twilight □ Datsik & Kill The Noise Lightspeed □ Datsik Feat. -

Stress Overload Basics

- 1 - Terms and Conditions LEGAL NOTICE The Publisher has strived to be as accurate and complete as possible in the creation of this report, notwithstanding the fact that he does not warrant or represent at any time that the contents within are accurate due to the rapidly changing nature of the Internet. While all attempts have been made to verify information provided in this publication, the Publisher assumes no responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretation of the subject matter herein. Any perceived slights of specific persons, peoples, or organizations are unintentional. In practical advice books, like anything else in life, there are no guarantees of income made. Readers are cautioned to reply on their own judgment about their individual circumstances to act accordingly. This book is not intended for use as a source of legal, business, accounting or financial advice. All readers are advised to seek services of competent professionals in legal, business, accounting and finance fields. You are encouraged to print this book for easy reading. - 2 - Table Of Contents Foreword Chapter 1: Stress Overload Basics Chapter 2: Understand How You Respond To Stress Chapter 3: Cognitive Signs And Symptoms Of Stress Chapter 4: Physical Signs And Symptoms Of Stress Chapter 5: How Much Is Too Much Chapter 6: Effects Of Chronic Stress On The Brain Chapter 7: Effects Of Chronic Stress On The Body Chapter 8: Effects Of Chronic Stress On Relationships Chapter 9: Learn How To Relax Chapter 10: The Benefits Of Not Getting Into The Stress Cycle For Your Health Wrapping Up - 3 - Foreword Stress is defined as our body’s way of responding to challenges. -

Responding to COVID-19 a Special Edition Honoring the Healthcare Heroes of Hennepin Healthcare 3Ws

ImpactHENNEPIN HEALTHCARE FOUNDATION GENEROSITY HAPPENS HERE Responding to COVID-19 A special edition honoring the healthcare heroes of Hennepin Healthcare 3Ws Demonstrate your concern for others as well as yourself by following the 3 Ws. Wear Your Mask TURNING CHA Jennifer DeCubellis, CEO Hennepin Healthcare When I became CEO of Hennepin Healthcare, I had big plans. Most of Wash Your Hands them involved listening, learning and developing new ways to move our mission forward in helping our community. In a matter of weeks it became apparent COVID-19 had other plans, and the mission of our institution was going to be put to the test like never before. As a trauma center, we’re used to urgency, we’re just not used to Watch Your Distance urgency lasting so long. This pandemic is an “all hands on deck” moment, a call to action. The most reassuring part of it has been seeing 6 ft. how quickly people have responded, turning the chaos into confidence. Our staff, across the board, did not run away. Instead, they said, “We’ve got this.” They jumped in, in creative ways, aimed at making a difference and being there for each other and for our community. The Impact newsletter is published twice a year by the Hennepin Healthcare Foundation. Editor is We serve a particularly vulnerable Amy Carlson. Contributing writers in this issue are population in Minnesota. When you Amy Carlson, Tom Hayes, Chris Hill, and Brian Lucas. hear about social determinants of Design by Karen Olson. Contributing photographers health and high risk factors for Scott Streble and self-submissions. -

Open Laura Guley 2020.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF MUSICAL THEATRE UTILIZING THE LINKLATER METHOD OF BREATHING TO CREATE AND RECREATE AUTHENTIC EMOTION LAURA GULEY SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in Musical Theatre with honors in Musical Theatre Reviewed and approved* by the following: Raymond Sage Voice for Musical Theatre Thesis Supervisor Raymond Sage Voice for Musical Theatre Honors Advisor Susan B. Russell Literature and Criticism, Playwriting, History of Musical Theatre Faculty Reader * Electronic approvals are on file. i ABSTRACT It’s no secret that many actors of any age, background, or level of success can struggle with their mental health. While there are many factors that contribute to this, such as feelings of rejection, and needing to be “good enough”, I believe there is a facet of acting taught in schools that contributes to the mental health struggles actors face. There is a technique of acting taught to students called Method Acting. This technique requires the student to draw on their own personal experiences and memories in order to understand or create a character. This could involve a student exploring negative memories, or living as that character for a period of time, in order to relate to the psyche of the character. However, forcing yourself to reopen healed wounds of heartbreak and grief, or making unhealthy choices for the sake of the character is not always a sustainable method of acting. Therefore, I am proposing that actors and teachers explore a different route to getting into character through breath. -

The Way That I'm Crying So Hard I Have to Gasp for Air� by Eli Brody and 5,134 Friends Chapter 1: the Way That Old Guy Is Looking at Her with Such Contempt

The Way That I'm Crying so Hard I Have to Gasp For Air By Eli Brody and 5,134 friends Chapter 1: The way that old guy is looking at her with such contempt The way that Grantham Dominos handled our complaint tonight. The way that guy does. The way that iii. The way that Bitsy and Lulu jump up and lay on me the second I sit down here! The way that i missing,you knew where i am,i know you there,but seems like you're gone in every single thing's. The way that ITV introduced the John Lewis Christmas advert (it was the entire ad break in fact). The way that is not like God. The way that McKaylee's mother stares during her performances is pretty scary and uncomfortable, lol. The way that shit look just make me wanna throw up like why its so thick like that. The way that girl (sugar-coating) picked up the cash I dropped and put it in her bra. The way that turned out was. The way that blazer fits to his back. The way that we come together is truly amazing, and the love we show for each other is inspiring. The way that she used to miss me. The way that people walk when drunk. The way that I speak, Im out in these. The way that person looks, act, personality you can't ever forget. The way that most did. The way that its animals are treated. The way that I was before, hungry for what was to come. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Citytv New Year's Bash, 2010 25Th

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Citytv New Year’s Bash, 2010 25th Annual Live Broadcast from Nathan Phillips Square Thursday, December 31 at 10pm on Citytv Hosts Gord Martineau, Tracy Moore, Kevin Frankish and Dina Pugliese Musical Performances by: Anjulie, Jarvis Church, Kardinal Offishall, Karl Wolf, The Mission District and ROCK OF AGES. Plus New Year’s Greetings from Some of the Stars from Your Favourite Citytv Primetime Programs (Toronto – December 7, 2009) This is one party you won’t want to miss! ‘Sing’ in the New Year with Citytv at the 25th annual festivities and live broadcast of Citytv New Year’s Bash, 2010 from Nathan Phillips Square. One of the biggest New Year’s celebrations in Canada, this year’s special outdoor, free-concert is hosted by Gord Martineau, Tracy Moore, Kevin Frankish and Dina Pugliese. Tune in to Citytv for all of the fun, Thursday, December 31 at 10:00pm ET/CT/MT/PT. For artwork visit, www.rogersmediatv.ca “Citytv has had the pleasure of hosting some of the biggest names in Canadian music as part of our annual New Year’s celebrations for a quarter of a century”, commented Maureen Rogers, Vice President and General Manager, Citytv, Toronto. “Citytv viewers have made it a holiday tradition to brave the cold and ring in the New Year with Citytv at the live-broadcast from Nathan Phillips Square or tune in from home at their own celebrations with family and friends.” Send off 2009 with a bang with an alcohol-free evening of entertainment --- bring out the hot chocolate, long johns and flannel blankets to keep you warm. -

DJ Music Catalog by Title

Artist Title Artist Title Artist Title Dev Feat. Nef The Pharaoh #1 Kellie Pickler 100 Proof [Radio Edit] Rick Ross Feat. Jay-Z And Dr. Dre 3 Kings Cobra Starship Feat. My Name is Kay #1Nite Andrea Burns 100 Stories [Josh Harris Vocal Club Edit Yo Gotti, Fabolous & DJ Khaled 3 Kings [Clean] Rev Theory #AlphaKing Five For Fighting 100 Years Josh Wilson 3 Minute Song [Album Version] Tank Feat. Chris Brown, Siya And Sa #BDay [Clean] Crystal Waters 100% Pure Love TK N' Cash 3 Times In A Row [Clean] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful Frenship 1000 Nights Elliott Yamin 3 Words Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful [Louie Vega EOL Remix - Clean Rachel Platten 1000 Ships [Single Version] Britney Spears 3 [Groove Police Radio Edit] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And A$AP #Beautiful [Remix - Clean] Prince 1000 X's & O's Queens Of The Stone Age 3's & 7's [LP] Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel And Jeezy #Beautiful [Remix - Edited] Godsmack 1000hp [Radio Edit] Emblem3 3,000 Miles Mariah Carey Feat. Miguel #Beautiful/#Hermosa [Spanglish Version]d Colton James 101 Proof [Granny With A Gold Tooth Radi Lonely Island Feat. Justin Timberla 3-Way (The Golden Rule) [Edited] Tucker #Country Colton James 101 Proof [The Full 101 Proof] Sho Baraka feat. Courtney Orlando 30 & Up, 1986 [Radio] Nate Harasim #HarmonyPark Wrabel 11 Blocks Vinyl Theatre 30 Seconds Neighbourhood Feat. French Montana #icanteven Dinosaur Pile-Up 11:11 Jay-Z 30 Something [Amended] Eric Nolan #OMW (On My Way) Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [KBCO Edit] Childish Gambino 3005 Chainsmokers #Selfie Rodrigo Y Gabriela 11:11 [Radio Edit] Future 31 Days [Xtra Clean] My Chemical Romance #SING It For Japan Michael Franti & Spearhead Feat. -

Party Tunes Dj Service Artist Title 112 Dance with Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream

Party Tunes Dj Service www.partytunesdjservice.com Artist Title 112 Dance With Me 112 It's Over Now 112 Peaches & Cream 112 Peaches & Cream (feat. P. Diddy) 112 U Already Know 213 Groupie Love 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Creatures 311 It's Alright [Album Version] 311 Love Song 311 You Wouldn't Believe 702 Steelo [Album Edit] $th Ave Jones Fallin' (r)/M/A/R/R/S Pump Up the Volume (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ame iro Rondo (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Chance Chase Classroom (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Creme Brule no Tsukurikata (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Duty of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Eyecatch (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Great escape (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Happy Monday (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Hey! You are lucky girl (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kanchigai Hour (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kaze wo Kiite (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Ki Me Ze Fi Fu (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kitchen In The Dark (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Kotori no Etude (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Lost my pieces (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari love on the balloon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Magic of love (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Monochrome set (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Morning Glory (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Next Mission (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Onna no Ko no Kimochi (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Psychocandy (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari READY STEADY GO! (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Small Heaven (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Sora iro no Houkago (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Startup (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tears of dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Tiger VS Dragon (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Todoka nai Tegami (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yasashisa no Ashioto (ToraDora!) Hashimoto Yukari Yuugure no Yakusoku (ToraDora!) Horie Yui Vanilla Salt (TV-SIZE) (ToraDora!) Kugimiya Rie, Kitamura Eri & Horie Yui Pre-Parade (TV-SIZE) .38 Special Hold on Loosely 1 Giant Leap f. -

Potential Energy and the Three Odalisques

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2014 Potential Energy and the Three Odalisques Yamins Roxanne Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Fine Arts Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/3457 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Roxanne Yamins 2014 All Rights Reserved POTENTIAL ENERGY AND THE THREE ODALISQUES A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art in Sculpture + Extended Media at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Roxanne Yamins Bachelor of Fine Arts, Cornell University, 2012 Director: Ester Partegas, Assistant Professor, Sculpture + Extended Media Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia May 2014 ii POTENTIAL ENERGY AND THE THREE ODALISQUES TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iii PART 1 RANGE, GESTURE, AND BEHAVIORAL APPARATUS 1 POTENTIAL ENERGY 3 EMPATHY, MATERIALS, AND OBJECT CHOICE 4 PART 2 TWO MANNEQUINS IN THE 20TH CENTURY 9 CHARTS FOR ME AND YOU Bouncing Songs 12 Star Trek: The Next Generation: Log 13 Real and Proposed P.E.E. Machines 14 LIST OF LITERARY INFLUENCES 16 ABSTRACT POTENTIAL ENERGY AND THE THREE ODALISQUES By Roxanne A. J. Yamins, MFA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Art in Sculpture + Extended Media at Virginia Commonwealth University. -

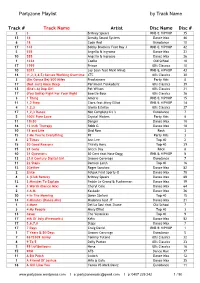

[email protected] L P: 0407 229 242 1 / 90 Partyzone Playlist by Track Name

Partyzone Playlist by Track Name Track # Track Name Artist Disc Name Disc # 2 3 Britney Spears RNB & HIPHOP 35 13 16 Sneaky Sound System Dance Max 46 6 18 Code Red Eurodance 10 17 143 Bobby Brackins Feat Ray J RNB & HIPHOP 42 5 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 23 10 555 Angello & Ingrosso Dance Max 26 1 1234 Coolio Old School10 17 1999 Prince 80's Classics10 10 2012 Jay Sean feat Nicki Minaj RNB & HIPHOP 43 18 (1,2,3,4,5) Senses Working Overtime XTC 80's Classics30 3 (I'm Gonna Be) 500 Miles Proclaimers Party Hits8 17 (Not Just) Knee Deep Parliment Funkadelic 80's Classics 39 13 (She's A) Bop Girl Pat Wilson 80's Classics 31 17 (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right Beastie Boys 80's Classics 36 3 1 Thing Amerie RNB & HIPHOP 15 11 1,2 Step Ciara feat Missy Elliot RNB & HIPHOP 14 4 1,2,3 Gloria Estefan 80's Classics 27 17 1,2,3 Dance Not Complete DJ 's Eurodance 7 5 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters Party Hits 8 11 11h30 Danger Dance Max18 16 12 Inch Therapy Robb G Dance Max 18 10 18 and Life Skid Row Rock 3 15 2 Me You're Everything 98° Party Hits 3 8 2 Times Ann Lee Top 40 2 15 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Top 40 29 15 21 Guns Green Day Rock 8 10 21 Questions 50 Cent feat Nate Dogg RNB & HIPHOP 8 13 21st Century Digital Girl Groove Coverage Eurodance 7 11 22 Steps Damien Leith Top 40 16 12 2Gether Roger Sanchez Dance Max 82 2 2nite Felguk Feat Sporty-O Dance Max 78 8 3 (Club Remix) Britney Spears Dance Max 68 12 3 Minutes To Explain Fedde Le Grand & Funkerman Dance Max 19 4 3 Words (Dance Mix) Cheryl Cole Dance Max 64 2 4 A.M Kaskade Dance Max -

FACTOR Annual Report 2012-13

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Music Fund and of Canada’s Private Radio Broadcasters. TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR THE FISCAL PERIOD COVERING APRIL 1, 2012 - MARCH 31, 2013 2 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR 3 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT 4 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION Our Mandate and History Our Funding Partners The Nature of Our Funding Overview of 2012-2013 13 OUR PROGRAMS Looking Ahead: Our Programs for 2013 and Beyond Our 2012-2013 Programs New Talent Development Sound Recordings Emerging Talent Sound Recordings Marketing & Promotion Tour & Showcase Support Industry Support Sponsorship Collective Initiatives 22 FUNDING PROCESS Assessment of Applications Juries Our Jurors 26 #FACTORfunded RECOGNITION Canadian Awards Canadian Certifications 33 OUR BOARD OF DIRECTORS 35 OUR TEAM 36 OUR REGIONAL REPRESENTATIVES 37 REQUESTS AND COMMITMENTS BY PROGRAM 38 APPLICATIONS SUBMITTED AND APPROVED BY PROVINCE 40 CONTRIBUTING RADIO BROADCASTERS 41 FINANCIAL RESULTS Requests and Commitments Outstanding Commitments 43 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage Canada Music Fund and of Canada’s Private Radio Broadcasters. MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR This year has been filled with significant change and considerable accomplishments, culminating with the launch of our new program and application system FACTOR 2.0 in April 2013. The goal of FACTOR 2.0 was simple: design a system and programs that award funding based on merit, are transparent and easy to use, and reflect the current business models of the Canadian independent music industry. This type of change was long overdue, as FACTOR’s previous funding model was based heavily on out-of-date business practices, which focused primarily on the physical sale of recorded music.