Apple Inc. and Next Software, Inc. V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Motorola SOW NICE-CISCO Integratin

WILLIAMSON COUNTY JUNE 11, 2018 NICE CISCO PHONE SYSTEM UPGRADE The design, technical, pricing, and other information (“Information”) furnished with this submission is proprietary and/or trade secret information of Motorola Solutions, Inc. (“Motorola Solutions”) and is submitted with the restriction that it is to be used for evaluation purposes only. To the fullest extent allowed by applicable law, the Information is not to be disclosed publicly or in any manner to anyone other than those required to evaluate the Information without the express written permission of Motorola Solutions. MOTOROLA, MOTO, MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS, and the Stylized M Logo are trademarks or registered trademarks of Motorola Trademark Holdings, LLC and are used under license. All other trademarks are the property of their respective owners. © 2018 Motorola Solutions, Inc. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Letter .......................................................................................................... Section 1 System Description ......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 NICE CISCO Phone Integration Solution Overview ......................................................... 1-1 1.2 Phone Arbitration Solution Overview ............................................................................... 1-2 1.3 Responsiblities and Dependencies .................................................................................. 1-3 1.4 NRX Overview ................................................................................................................ -

We Need Net Neutrality As Evidenced by This Article to Prevent Corporate

We need Net Neutrality as evidenced by this article to prevent corporate censorship of individual free speech online, whether its AOL censoring DearAOL.com emails protesting their proposed email fee for prioritized email delivery that evades spam filters, AT&T censoring Pearl Jam which this article is about, or Verizon Wireless censoring text messages from NARAL Pro Choice America. If the FCC won't reclassify broadband under Title II the FTC should regulate Net Neutrality, also the DOJ should investigate corporations engaging in such corporate censorship and if they are violating competition laws break them up. Pearl Jam came out in favor of net neutrality after AT&T censored a broadcast a performance they did in Chicago last Sunday. I guess AT&T didn?t like Pearl Jam?s anti-Bush message. I don?t know if Pearl Jam?s sudden embrace of net neutrality is out of ignorance, or if it?s retaliation. It doesn?t really matter because it should help bring some more awareness to the issue. Here?s the issue with net neutrality, in a nutshell. AT&T wants to charge companies like Amazon, eBay, and Google when people like you and me access their web pages. And if the companies don?t pay, AT&T will make the web sites slower. The idea is that if one company doesn?t pay the fees but a competitor does, AT&T customers will probably opt to use the faster services. IT"S WORTH NOTING: Without content, an Internet connection has no value. Proponents say AT&T built the infrastructure, so they have the right to charge whoever uses it. -

WHITE PAPER Encrypted Traffic Management January 2016

FRAUNHOFER INSTITUTE FOR COMMUNICATION, INFORMATION PROCESSIN G AND ERGONOMICS FKI E WHITE PAPER ENCRYPTED TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT WHITE PAPER Encrypted Traffic Management January 2016 Raphael Ernst Martin Lambertz Fraunhofer Institute for Communication, Information Processing and Ergonomics FKIE in Wachtberg and Bonn. Project number: 108146 Project partner: Blue Coat Systems Inc. Fraunhofer FKIE White paper Encrypted Traffic Management 3 | 33 Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................... 5 2 The spread of SSL ................................................................................. 6 3 Safety issues in previous versions of SSL ............................................... 8 4 Malware and SSL ................................................................................... 9 5 Encrypted Traffic Management .............................................................. 11 5.1 Privacy ...................................................................................................................... 12 5.1.1 Requirements ............................................................................................................ 12 5.2 Compatibility ............................................................................................................ 12 5.2.1 Requirements ............................................................................................................ 12 5.3 Performance ............................................................................................................ -

Download Gtx 970 Driver Download Gtx 970 Driver

download gtx 970 driver Download gtx 970 driver. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67a229f54fd4c3c5 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. GeForce Windows 10 Driver. NVIDIA has been working closely with Microsoft on the development of Windows 10 and DirectX 12. Coinciding with the arrival of Windows 10, this Game Ready driver includes the latest tweaks, bug fixes, and optimizations to ensure you have the best possible gaming experience. Game Ready Best gaming experience for Windows 10. GeForce GTX TITAN X, GeForce GTX TITAN, GeForce GTX TITAN Black, GeForce GTX TITAN Z. GeForce 900 Series: GeForce GTX 980 Ti, GeForce GTX 980, GeForce GTX 970, GeForce GTX 960. GeForce 700 Series: GeForce GTX 780 Ti, GeForce GTX 780, GeForce GTX 770, GeForce GTX 760, GeForce GTX 760 Ti (OEM), GeForce GTX 750 Ti, GeForce GTX 750, GeForce GTX 745, GeForce GT 740, GeForce GT 730, GeForce GT 720, GeForce GT 710, GeForce GT 705. -

Contract Overview Prior to Utilizing This Contract, the User Should Read the Contract in Its Entirety

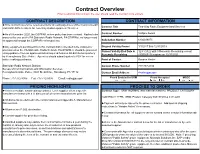

Contract Overview Prior to utilizing this contract, the user should read the contract in its entirety. CONTRACT DESCRIPTION CONTRACT INFORMATION ►This contract covers the requirements for all using Agencies of the Commonwealth Two-Way Radio Equipment and Services and COSTARS members for Two-Way Radio Equipment/ Services. Contract Title ►As of November 2020, the COPPAR review policy has been revised. Radios to be Contract Number Multiple Award procured for use on the PA Statewide Radio Network, PA-STARNet, no longer must be approved through the COPPAR review process. Solicitation Number 6100039075 ►Any equipment purchased from this contract that is intended to be installed or Original Validity Period 1/1/2017 thru 12/31/2019 provisioned on the PA Statewide Radio Network, PA-STARNet, should be procured Current Validity End Date & 12/31/2022 with 0 Renewals Remaining except using guidance from an approved radios/required features list distributed quarterly Renewals Remaining 4400020114 expires on 12/31/2021 by Pennsylvania State Police. Agencies should submit quotes to PSP for review before making purchases. Point of Contact Raeden Hosler Statewide Radio Network Division Contact Phone Number 717-787-4103 Bureau of Communications and Information Services Pennsylvania State Police, 8001 Bretz Drive, Harrisburg, PA 17112 Contact Email Address [email protected] Phone: 717-772-8005 Fax: 717-772-8097 Email: [email protected] Pcard Enabled in SRM Pcard Accepted MSCC Yes No Yes No Yes No PRICING HIGHLIGHTS PROCESS TO ORDER ►This is a multiple award catalog contract. Each supplier offers a specific Contract Type: SRM: NORMAL (has material masters), PRODUCT CATEGORY manufacturer brand with a % discount off of current manufacturer price list. -

Untangling a Worldwide Web Ebay and Paypal Were Deeply Integrated

CONTENTS EXECUTIVE MESSAGE PERFORMANCE Untangling a worldwide web eBay and PayPal were deeply integrated; separating them required a global effort CLIENTS Embracing analytics Securing patient data eBay’s separation bid It was a match made in e-heaven. In 2002, more than 70 During the engagement, more than 200 Deloitte Reducing IT risk percent of sellers on eBay, the e-commerce giant, accepted professionals helped the client: Audits that add value PayPal, the e-payment system of choice. So, for eBay, the • Separate more than 10,000 contracts. Raising the audit bar US$1.5 billion acquisition of PayPal made perfect sense. Not • Build a new cloud infrastructure to host 7,000 Blockchain link-up only could the online retailer collect a commission on every virtual servers and a new enterprise data Trade app cuts costs item sold, but it also could earn a fee from each PayPal warehouse, one of the largest in the world. Taking on corruption transaction. • Prepare more than 14,000 servers to support the split of more than 900 applications. TALENT Over time, however, new competitors emerged and • Migrate more than 18,000 employee user profiles new opportunities presented themselves, leading eBay and 27,000 email accounts to the new PayPal SOCIETY management to realize that divesting PayPal would allow environment. both companies to capitalize on their respective growth • Relocate 4,500-plus employees from 47 offices. “This particular REPORTING opportunities in the rapidly changing global commerce and • Launch a new corporate network for PayPal by engagement was payments landscape. So, in September 2014, eBay’s board integrating 13 hubs and 83 office locations. -

Apache Spot: a More Effective Approach to Cyber Security

SOLUTION BRIEF Data Center: Big Data and Analytics Security Apache Spot: A More Effective Approach to Cyber Security Apache Spot uses machine learning over billions of network events to discover and speed remediation of attacks to minutes instead of months—streamlining resources and cutting risk exposure Executive Summary This solution brief describes how to solve business challenges No industry is immune to cybercrime. The global “hard” cost of cybercrime has and enable digital transformation climbed to USD 450 billion annually; the median cost of a cyberattack has grown by through investment in innovative approximately 200 percent over the last five years,1 and the reputational damage can technologies. be even greater. Intel is collaborating with cyber security industry leaders such as If you are responsible for … Accenture, eBay, Cloudwick, Dell, HP, Cloudera, McAfee, and many others to develop • Business strategy: You will better big data solutions with advanced machine learning to transform how security threats understand how a cyber security are discovered, analyzed, and corrected. solution will enable you to meet your business outcomes. Apache Spot is a powerful data aggregation tool that departs from deterministic, • Technology decisions: You will learn signature-based threat detection methods by collecting disparate data sources into a how a cyber security solution works data lake where self-learning algorithms use pattern matching from machine learning to deliver IT and business value. and streaming analytics to find patterns of outlier network behavior. Companies use Apache Spot to analyze billions of events per day—an order of magnitude greater than legacy security information and event management (SIEM) systems. -

Ebay V.Bidder's Edge

eBay v. Bidder's Edge 1 eBay v. Bidder's Edge U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California (N.D. Cal.) Map Location San Jose, CA Appeals to Ninth Circuit Established August 5, 1886. Judges assigned 14 Chief judge Vaughn R. Walker [1] Official site eBay v. Bidder's Edge, 100 F.Supp.2d 1058 (N.D. Cal. 2000) [2], was a leading case applying the trespass to chattels doctrine to online activities. In 2000, eBay, an online auction company, successfully used the 'trespass to chattels' theory to obtain a preliminary injunction preventing Bidder’s Edge, an auction data aggregator, from using a 'crawler' to gather data from eBay’s website.[3] The opinion was a leading case applying 'trespass to chattels' to online activities, although its analysis has been criticized in more recent jurisprudence. Origins of dispute Bidder’s Edge (“BE”) was founded in 1997 as an “aggregator” of auction listings.[4] Its website provided a database of auction listings that BE automatically collected from various auction sites, including eBay.[5] Accordingly, BE’s users could easily search auction listings from throughout the web rather than having to go to each individual auction site.[6] An archived version of the Bidder’s Edge web page from November 9, 2000 from Archive.org is available here. [7]. In early 1998, eBay allowed BE to include Beanie Babies and Furbies auction listings in BE’s database.[8] It is unclear whether BE scraped these listings from eBay or linked to them in some other format. However, on April 24, 1999, eBay verbally approved BE automatically “crawling” the eBay web site for a period of 90 days.[9] During this time, the parties contemplated striking a formal license agreement.[10] These negotiations did not conclude successfully because the parties could not agree on technical issues.[11] Subsequently, in early 1999, BE added auction listings from many other sites in its database, including eBay’s. -

The Three Year Anniversary of Ebay V. Mercexchange

such as monetary damages, are inadequate to compensate for that injury; (3) that, con- The Three Year Anniversary sidering the balance of hardships between the parties, a remedy in equity is warranted; of eBay v. MercExchange: and (4) that the public interest would not be disserved by a permanent injunction. While both lower courts ostensibly applied A Statistical Analysis of this test, the Court held that they applied it incorrectly. The Court explained that there is no “general rule” requiring injunctive Permanent Injunctions relief in patent infringement cases. In his concurring opinion, Justice Kennedy BY ERNEST GRUMBLES III, RACHEL C. HUGHEY AND courts have been handling permanent considered on the issue of “patent trolls,” SUSAN PERERA injunctions. It is also valuable to review relevant Federal Circuit decisions to under- suggesting that monetary damages, rather than injunctive relief, may be sufficient Ernest Grumbles III is a partner in the stand how the court reviews those deci- compensation for non-practicing entities. Minneapolis office of Merchant & Gould sions—especially when the district court decides not to grant a permanent injunc- P.C. and focuses his practice on patent METHODOLOGY and trademark litigation and related tion. Unsurprisingly, since the eBay deci- portfolio counseling. He is also the host of sion, district courts have been willing to In an attempt to understand how the the intellectual property podcast BPGRadio. deny permanent injunctions after a finding district courts have applied eBay in the com. He may be reached at egrumbles@ of patent infringement—something that was three years since the decision, the authors merchantgould.com. -

The Future of Medical Device Patents: Categorical Exclusion After Ebay, Inc. V. Mercexchange, L.L.C. Final Page Numbers May Diff

NOTE THE FUTURE OF MEDICAL DEVICE PATENTS: CATEGORICAL EXCLUSION AFTER EBAY, INC. V. MERCEXCHANGE, L.L.C. Laura Masterson TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................... 275 I. PATENT LAW BASICS .................................................................................. 275 A. Policy Considerations .................................................................... 276 B. Patentability ................................................................................... 277 C. Patentable Subject Matter ............................................................. 278 II. PATENT INFRINGEMENT AND REMEDIES ................................................... 280 A. Direct Infringement ....................................................................... 281 B. Indirect Infringement – Contributory & Induced Infringement ..... 282 C. Remedies Generally ....................................................................... 282 III. CURRENT LANDSCAPE: PATENTABILITY OF MEDICAL DEVICES AND MEDICAL PROCEDURES ....................................................................... 284 A. FDA – Premarket Approval Process ............................................. 285 B. Extension of Patent Term ............................................................... 286 C. Infringement Under 35 U.S.C. 287(c) ........................................... 287 D. International Intellectual Property Treaties ................................. 289 IV. REMEDIES: PERMANENT INJUNCTIONS -

Citron Exposes the Vulnerability of Motorola Solutions…Price Target - $45

February 7, 2017 Citron Exposes the Vulnerability of Motorola Solutions…Price Target - $45 What would President Trump think about U.S. Law Enforcement Agencies Paying 5 TIMES the Prices Motorola Charges EU Countries? Background Motorola Solutions (NYSE:MSI) was created when Motorola spun off their telecommunications division in 2011. With an 85% market share of radio communications for law enforcement and other first responders (FR), Motorola has used its dominant position in a fragmented customer base to control the market for first responder communications in North America. Motorola also has a worldwide presence selling broadband networks and equipment though numerous partnerships. But it's time investors start to realize … How Motorola Really Makes Its Money! While Motorola’s has many operating divisions, the bulk of its profits come from selling overpriced handsets into its single source contracts in the United States….taking advantage of both tax payers and the first responder community. In fact, handset sales in the U.S. carry an 83.6% gross margin (see below), while device sales in Europe are at 9%. Citron’s analysis shows that U.S. device (handset) sales are contributing a whopping 76.7% of Motorola’s bottom line! Citron Reports on Motorola Solutions February 7, 2017 Page 1 of 13 Read on to be appalled!! From a series of articles reported by McClatchy last year: “The industry giant has landed scores of sole-source radio contracts and wielded enough pricing power to sell its glitzy handsets for as much as $7,000 apiece, at a taxpayer cost of hundreds of millions, if not billions, of dollars that could have been saved in a more competitive market." http://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/economy/article24779224.html#storylink=cpy Motorola Solutions has been coasting on a simple formula: Dote on police, fire and sheriff’s departments; woo contracting officials; pursue every angle to gain a sole-source deal or an inside track, and where possible, embed equipment with proprietary features so it can’t interact with competitors’ products. -

2013.05.13 Motorola Reply Brief (12-1548)

Case: 12-1548 Document: 191 Page: 1 Filed: 05/13/2013 NON-CONFIDENTIAL Appeal Nos. 2012-1548, 2012-1549 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT APPLE INC. AND NEXT SOFTWARE, INC. (formerly known as NeXT Computer Inc.), Appellants, v. MOTOROLA INC. (now known as Motorola Solutions, Inc.) AND MOTOROLA MOBILITY, INC., Appellees-Cross-Appellants, Appeals from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in case no. 11-CV-8540, Judge Richard A. Posner REPLY BRIEF OF APPELLEES-CROSS-APPELLANTS MOTOROLA MOBILITY LLC AND MOTOROLA SOLUTIONS, INC. Kathleen M. Sullivan David A. Nelson Edward J. DeFranco Stephen A. Swedlow QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP SULLIVAN, LLP 51 Madison Ave., 22nd Floor 500 W. Madison St., Suite 2450 New York, NY 10010 Chicago, IL 60661 (212) 849-7000 (312) 705-7400 Charles K. Verhoeven Brian C. Cannon QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART & SULLIVAN, LLP SULLIVAN, LLP 50 California St., 22nd Floor 555 Twin Dolphin Drive, 5th Floor San Francisco, CA 94111 Redwood Shores, CA 94065 (415) 875-6600 (650) 801-5000 Attorneys for Motorola Mobility LLC and Motorola Solutions, Inc. Case: 12-1548 Document: 191 Page: 2 Filed: 05/13/2013 CERTIFICATE OF INTEREST Counsel for Appellees-Cross-Appellants Motorola Mobility LLC and Motorola Solutions, Inc. certifies the following: 1. The full name of every party or amicus represented by me is: Motorola Mobility LLC, formerly known as Motorola Mobility, Inc. On June 22, 2012, Appellant Motorola Mobility, Inc. was converted into a Delaware limited liability company, changing its name to Motorola Mobility LLC.