The Sigma Tau Delta Rectangle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M I N U T E S Lane Regional Air Protection Agency Board of Directors Meeting Thursday January 9, 2019 1010 Main St, Springfield

M I N U T E S LANE REGIONAL AIR PROTECTION AGENCY BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING THURSDAY JANUARY 9, 2019 1010 MAIN ST, SPRINGFIELD, OR 97477 ATTENDANCE: Board: Mike Fleck - Chair - Cottage Grove; Joe Pishioneri – Vice Chair – Springfield; Mysti Frost - Eugene; Betty Taylor – Eugene; Jeannine Parisi – Eugene; Joe Berney – Lane County; Gabrielle Guidero – Springfield Absent: Charlie Hanna – Eugene; Kathy Nichols – Oakridge Staff: Merlyn Hough–Director; Debby Wineinger; Nasser Mirhosseyni; Max Hueftle; Beth Erickson; Kelly Conlon Others: Jim Daniels – CAC Chair; Kathy Lamberg – CAC Member; Josh Proudfoot – Good Company OPENING: Fleck called the meeting to order at 12:18 p.m. 1. Call to Order 2. ADJUSTMENTS TO THE AGENDA: None 3. PUBLIC PARTICIPATION: Howard Saxion – Eugene: Mr. Saxion is a resident of Eugene, representing himself. For background he currently serves as an at-large member on City of Eugene’s Sustainability Commission. He is a retired environmental professional. He and Merlyn Hough were on the International Board of Directors for Air & Waste Management Association. He is not speaking on behalf of the commission. They also have public comments during their meetings and there has been a lot of increased interest on air quality issues by the public, especially on particulate matter and air toxics. The commission formed a committee and we are in the process of getting ourselves educated on local issues. We are an advisory committee to the City Council and City Manager. As an outcome, we may have some recommendations to present to the City Council that would be forwarded to LRAPA. Saxion is particularly concerned about LRAPA’s budget and he knows local government is always strapped for money. -

Radiolovefest

BAM 2017 Winter/Spring Season #RadioLoveFest Brooklyn Academy of Music New York Public Radio* Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board Cynthia King Vance, Chair, Board of Trustees William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board John S. Rose, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Katy Clark, President Susan Rebell Solomon, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer Mayo Stuntz, Vice Chair, Board of Trustees Laura R. Walker, President & CEO *As of February 1, 2017 BAM and WNYC present RadioLoveFest Produced by BAM and WNYC February 7—11 LIVE PERFORMANCES Ira Glass, Monica Bill Barnes & Anna Bass: Three Acts, Two Dancers, One Radio Host: All the Things We Couldn’t Do on the Road Feb 7, 8pm; Feb 8, 7pm & 9:30pm, HT The Moth at BAM—Reckless: Stories of Falling Hard and Fast, Feb 9, 7:30pm, HT Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me®, National Public Radio, Feb 9, 7:30pm, OH Jon Favreau, Jon Lovett, and Tommy Vietor, Feb 10, 7:30pm, HT Snap Judgment LIVE!, Feb 10, 7:30pm, OH Bullseye Comedy Night, Feb 11, 7:30pm, HT BAMCAFÉ LIVE Curated by Terrance McKnight Braxton Cook, Feb 10, 9:30pm, BC, free Gerardo Contino y Los Habaneros, Feb 11, 9pm, BC, free Season Sponsor: Leadership support provided by The Joseph S. and Diane H. Steinberg Charitable Trust. Delta Air Lines is the Official Airline of RadioLoveFest. Audible is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. VENUE KEY BC=BAMcafé Forest City Ratner Companies is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. BRC=BAM Rose Cinemas Williams is a major sponsor of RadioLoveFest. -

Copyright 2015 Marie T. Winkelmann

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository Copyright 2015 Marie T. Winkelmann DANGEROUS INTERCOURSE: RACE, GENDER AND INTERRACIAL RELATIONS IN THE AMERICAN COLONIAL PHILIPPINES, 1898 - 1946 BY MARIE T. WINKELMANN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2015 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Augusto F. Espiritu, Chair Professor Kristin Hoganson Professor Leslie J. Reagan Professor David Roediger, University of Kansas ABSTRACT “Intercourse with them will be dangerous,” warned the Deputy Surgeon General to all U.S. soldiers bound for the Philippines. In his 1899 pamphlet on sanitation, Colonel Henry Lippincott alerted troops to the consequences of becoming too friendly with the native population of the islands. From the beginning of the U.S. occupation of the Philippines, interracial sexual contact between Americans and Filipinos was a threatening prospect, informing everything from how social intercourse and diplomacy was structured, to how the built environment of Manila was organized. This project utilizes a transnational approach to examine a wide range of interracial sexual relationships -from the casual and economic to the formal and long term- between Americans and Filipinos in the overseas colony from1898–1946. My dissertation explores the ways that such relations impacted the U.S. imperial project in the islands, one that relied on a degree of social proximity with Filipinos on the one hand, while maintaining a hard line of racial and civilizational hierarchy on the other. -

BTC Catalog 172.Pdf

Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. ~ Catalog 172 ~ First Books & Before 112 Nicholson Rd., Gloucester City NJ 08030 ~ (856) 456-8008 ~ [email protected] Terms of Sale: Images are not to scale. All books are returnable within ten days if returned in the same condition as sent. Books may be reserved by telephone, fax, or email. All items subject to prior sale. Payment should accompany order if you are unknown to us. Customers known to us will be invoiced with payment due in 30 days. Payment schedule may be adjusted for larger purchases. Institutions will be billed to meet their requirements. We accept checks, VISA, MASTERCARD, AMERICAN EXPRESS, DISCOVER, and PayPal. Gift certificates available. Domestic orders from this catalog will be shipped gratis via UPS Ground or USPS Priority Mail; expedited and overseas orders will be sent at cost. All items insured. NJ residents please add 7% sales tax. Member ABAA, ILAB. Artwork by Tom Bloom. © 2011 Between the Covers Rare Books, Inc. www.betweenthecovers.com After 171 catalogs, we’ve finally gotten around to a staple of the same). This is not one of them, nor does it pretend to be. bookselling industry, the “First Books” catalog. But we decided to give Rather, it is an assemblage of current inventory with an eye toward it a new twist... examining the question, “Where does an author’s career begin?” In the The collecting sub-genre of authors’ first books, a time-honored following pages we have tried to juxtapose first books with more obscure tradition, is complicated by taxonomic problems – what constitutes an (and usually very inexpensive), pre-first book material. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Packaging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3th639mx Author Galloway, Catherine Suzanne Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge Professor Jack Citrin, Chair Professor Eric Schickler Professor Taeku Lee Professor Tom Goldstein Fall 2012 Abstract Packaging Politics by Catherine Suzanne Galloway Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jack Citrin, Chair The United States, with its early consumerist orientation, has a lengthy history of drawing on similar techniques to influence popular opinion about political issues and candidates as are used by businesses to market their wares to consumers. Packaging Politics looks at how the rise of consumer culture over the past 60 years has influenced presidential campaigning and political culture more broadly. Drawing on interviews with political consultants, political reporters, marketing experts and communications scholars, Packaging Politics explores the formal and informal ways that commercial marketing methods – specifically emotional and open source branding and micro and behavioral targeting – have migrated to the -

National Song Binder

SONG LIST BINDER ——————————————- REVISED MARCH 2014 SONG LIST BINDER TABLE OF CONTENTS Complete Music GS3 Spotlight Song Suggestions Show Enhancer Listing Icebreakers Problem Solving Troubleshooting Signature Show Example Song List by Title Song List by Artist For booking information and franchise locations, visit us online at www.cmusic.com Song List Updated March 2014 © 2014 Complete Music® All Rights Reserved Good Standard Song Suggestions The following is a list of Complete’s Good Standard Songs Suggestions. They are listed from the 2000’s back to the 1950’s, including polkas, waltzes and other styles. See the footer for reference to music speed and type. 2000 POP NINETIES ROCK NINETIES HIP-HOP / RAP FP Lady Marmalade FR Thunderstruck FX Baby Got Back FP Bootylicious FR More Human Than Human FX C'mon Ride It FP Oops! I Did It Again FR Paradise City FX Whoomp There It Is FP Who Let The Dogs Out FR Give It Away Now FX Rump Shaker FP Ride Wit Me FR New Age Girl FX Gettin' Jiggy Wit It MP Miss Independent FR Down FX Ice Ice Baby SP I Knew I Loved You FR Been Caught Stealin' FS Gonna Make You Sweat SP I Could Not Ask For More SR Bed Of Roses FX Fantastic Voyage SP Back At One SR I Don't Want To Miss A Thing FX Tootsie Roll SR November Rain FX U Can't Touch This SP Closing Time MX California Love 2000 ROCK SR Tears In Heaven MX Shoop FR Pretty Fly (For A White Guy) MX Let Me Clear My Throat FR All The Small Things MX Gangsta Paradise FR I'm A Believer NINETIES POP MX Rappers Delight MR Kryptonite FP Grease Mega Mix MX Whatta Man -

The Heaven Shop Teacher’S Guide

The Heaven Shop Teacher’s Guide Produced by UNICEF Canada and Fitzhenry and Whiteside Table of Contents Introduction to Teacher’s Guide 3 Chapter 1 5 Getting Acquainted Chapter 2 7 Binti’s Hometown Chapter 3 9 Sisters Chapter 4 11 Dear Anne Landers Chapter 5 13 Priorities and Values Chapter 6 15 Complete the Thought Chapter 7 18 Who Said It? Chapter 8 21 What the Future Holds Chapter 9 23 Myths about HIV/AIDS Chapter 10 25 Making Decisions Chapter 11 27 HIV/AIDS – Peer Education Poster Chapter 12 30 On the Move Chapter 13 32 An Outsider - Tableau Chapter 14 34 Inner Thoughts Chapter 15 36 HIV/AIDS - Roleplay Chapter 16 39 Moral Dilemmas – Corridor of Voices Chapter 17 41 Love Poem Chapter 18 44 Rest in Peace - Character Epitaph Chapter 19 46 Then and Now Chapter 20 49 Postcard Home About the Author 51 Facts about Orphans and Families affected by HIV/AIDS 52 2 Introduction to the Teacher’s Guide The Heaven Shop is appropriate for students from grades 7 to 9 as a text for independent reading, guided reading or literature circles. It can also be used as a whole class novel to teach reading strategies and to explore the issue of orphans and families affected by HIV/AIDS. The Teacher’s Guide is divided into twenty sections. Each section contains a plot summary, guiding questions for pre- and post- reading discussion, and an extension activity. The pre- and post reading questions are meant to assess literal comprehension, as well as extend thinking and encourage inference. -

A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition

A DICTIONARY OF Literary and Thematic Terms Second Edition EDWARD QUINN A Dictionary of Literary and Thematic Terms, Second Edition Copyright © 2006 by Edward Quinn All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Quinn, Edward, 1932– A dictionary of literary and thematic terms / Edward Quinn—2nd ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8160-6243-9 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Criticism—Terminology. 2. Literature— Terminology. 3. Literature, Comparative—Themes, motives, etc.—Terminology. 4. English language—Terms and phrases. 5. Literary form—Terminology. I. Title. PN44.5.Q56 2006 803—dc22 2005029826 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can fi nd Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfi le.com Text design by Sandra Watanabe Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America MP FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Contents Preface v Literary and Thematic Terms 1 Index 453 Preface This book offers the student or general reader a guide through the thicket of liter- ary terms. -

© Copyrighted by Charles Ernest Davis

SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Davis, Charles Ernest, 1933- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:54:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288393 This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 70-5237 DAVIS, Charles Ernest, 1933- SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY. University of Arizona, Ph.D., 1969 Education, theory and practice University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan © COPYRIGHTED BY CHARLES ERNEST DAVIS 1970 iii SELECTED WORKS OF LITERATURE AND READABILITY by Charles Ernest Davis A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY .In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 19 6 9 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE I hereby recommend that this dissertation prepared under my direction by Charles Ernest Davis entitled Selected Works of Literature and Readability be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy PqulA 1- So- 6G Dissertation Director Date After inspection of the final copy of the dissertation, the following members of the Final Examination Committee concur in its approval and recommend its acceptance:" *7-Mtf - 6 7-So IdL 7/3a This approval and acceptance is contingent on the candidate's adequate performance and defense of this dissertation at the final oral examination; The inclusion of this sheet bound into the library copy of the dissertation is evidence of satisfactory performance at the final examination. -

“Justice League Detroit”!

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! t 201 2 A ugus o.58 N . 9 5 $ 8 . d e v r e s e R s t h ® g i R l l A . s c i m o C C IN THE BRONZE AGE! D © & THE SATELLITE YEARS M T a c i r e INJUSTICE GANG m A f o e MARVEL’s JLA, u g a e L SQUADRON SUPREME e c i t s u J UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CROSSOVERS 7 A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN 0 8 2 “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY 6 7 7 CONWAY & DAN JURGENS 2 8 5 6 And the team fans 2 8 love to hate — 1 “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “BaTman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray . s c i m COVER COLORIST o C BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury .........................................................2 Glenn “Green LanTern” WhiTmore C D © PROOFREADER & Whoever was sTuck on MoniTor DuTy FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 M T . A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators a c i r SPECIAL THANKS e m Jerry Boyd A Rob Kelly f o Michael Browning EllioT S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers ................29 e u Rich Buckler g Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… a e L Russ Burlingame Brad MelTzer e c i T Snapper Carr Mi ke’s Amazing s u J Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme ....................................33 e h T ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders g n i r Gerry Conway Eri c Nolen- r a T s DC Comics WeaThingTon , ) 6 J. -

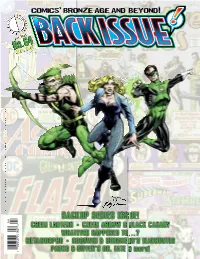

Backup Series Issue! 0 8 Green Lantern • Green Arrow & Black Canary 2 6 7 7

0 4 No.64 May 201 3 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 METAMORPHO • GOODWIN & SIMONSON’S MANHUNTER GREEN LANTERN • GREEN ARROW & BLACK CANARY COMiCs PASKO & GIFFEN’S DR. FATE & more! , WHATEVER HAPPENED TO…? BACKUP SERIES ISSUE! bROnzE AGE AnD bEYOnD i . Volume 1, Number 64 May 2013 Celebrating the Best Comics of Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTISTS Mike Grell and Josef Rubinstein COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . .2 PROOFREADER Rob Smentek FLASHBACK: The Emerald Backups . .3 Green Lantern’s demotion to a Flash backup and gradual return to his own title SPECIAL THANKS Jack Abramowitz Robert Greenberger FLASHBACK: The Ballad of Ollie and Dinah . .10 Marc Andreyko Karl Heitmueller Green Arrow and Black Canary’s Bronze Age romance and adventures Roger Ash Heritage Comics Jason Bard Auctions INTERVIEW: John Calnan discusses Metamorpho in Action Comics . .22 Mike W. Barr James Kingman The Fab Freak of 1001-and-1 Changes returns! With loads of Calnan art Cary Bates Paul Levitz BEYOND CAPES: A Rose by Any Other Name … Would be Thorn . .28 Alex Boney Alan Light In the back pages of Lois Lane—of all places!—sprang the inventive Rose and the Thorn Kelly Borkert Elliot S! Maggin Rich Buckler Donna Olmstead FLASHBACK: Seven Soldiers of Victory: Lost in Time Again . .33 Cary Burkett Dennis O’Neil This Bronze Age backup serial was written during the Golden Age Mike Burkey John Ostrander John Calnan Mike Royer BEYOND CAPES: The Master Crime-File of Jason Bard . -

Special Southampton Writers Spring Edition

The MFA Program in Writing & Literature Robert Reeves Director Carla Caglioti Associate Director 239 Montauk Highway Southampton, NY 11968 Adrienne Unger 631.632.5030 Administrative Coordinator www.stonybrook.edu/mfa SPECIAL SOUTHAMPTON WRITERS Alan Alda Kaylie Jones Jon Robin Baitz Matthew Klam SPRING EDITION Melissa Bank Mitchell Kriegman Upcoming Events Magdalene Brandeis Christian McLean MFA in Writing & Literature • Stony Brook Southampton • Winter/Spring 2011 William Burford Marsha Norman Writers Speak Will Chandler David Rakoff Billy Collins Roger Rosenblatt On the Horizon: Accolades, New Work & Upcoming Events Join us on Wednesday Evenings Jules Feiffer Julie Sheehan in Southampton (on Mondays in Manhattan) at 7 p.m. during Neal Gabler Lou Ann Walker Spring semester for this Robert Emmett Ginna Emma Walton Hamilton Roger Rosenblatt Does It Again illuminating, entertaining series Stephen Hamilton John Westermann of talks by leading writers. Annette Handley Chandler Meg Wolitzer n the heels of his bestseller, Making Toast, Roger Rosenblatt’s newest book, Unless It Moves Ursula Hegi the Human Heart has just been published by Ecco, a Harper Collins imprint, and is already in bookstores. Subtitled The Craft and Art of Writing, this book has special significance for Stony Brook Southampton’s faculty and students since Roger’s 2008 “Writing Everything” class is used as a narrative vehicle. The cast of (real) characters is identified by first names only but will be immediately recognizable to members of our community. Written with the same humor and humanist generosity that endears Roger to his students and fellow faculty, Unless It Moves the Human Heart is an instructive reflection on and from his classes from which both writers and teachers will gain useful insights and will be a treasured memento for all who have been priviledge to participate.