What I Do While I Am Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1Wayfrank Ayegirl

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1wayfrank Ayegirl - Single Ayegirl Streaming 2017 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Best of 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Dreams (Radio Version) Streaming 2017 2 Chainz TrapAvelli Tre El Chapo Jr Streaming 2017 2 Unlimited Get Ready for This - Single Get Ready for This (Yar Rap Edit) Streaming 2017 3LAU Fire (Remixes) - Single Fire (Price & Takis Remix) Streaming 2017 4Pro Smiler Til Fjender - Single Smiler Til Fjender Streaming 2017 666 Supa-Dupa-Fly (Remixes) - EP Supa-Dupa-Fly (Radio Version) Lets Lurk (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Streaming 2017 67 Liquez) No Hook (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Liquez) Streaming 2017 6LACK Loyal - Single Loyal Streaming 2017 8Ball Julekugler - Single Julekugler Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 Behøver ikk Behøver ikk (feat. Milo) Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 DE VED DET DE VED DET Streaming 2017 A Billion Robots This Is Melbourne - Single This Is Melbourne Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember Homesick (Special Edition) If It Means a Lot to You Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember What Separates Me from You All I Want Streaming 2017 A Flock of Seagulls Wishing: The Very Best Of I Ran Streaming 2017 A.CHAL Welcome to GAZI Round Whippin' Streaming 2017 A2M I Got Bitches - Single I Got Bitches Streaming 2017 Abbaz Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig - Single Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig Streaming 2017 Abbaz Harakat (feat. Gio) - Single Harakat (feat. Gio) Streaming 2017 ABRA Rose Fruit Streaming 2017 Abstract Im Good (feat. Roze & Drumma Battalion) Im Good (feat. Blac) Streaming 2017 Abstract Something to Write Home About I Do This (feat. -

Deadmau5 Teaches Electronic Music Production 1

DEADMAU5 TEACHES ELECTRONIC MUSIC PRODUCTION 1 v1.0 WELCOME TO MASTERCLASS DEADMAU5 TEACHES ELECTRONIC MUSIC PRODUCTION 2 You have to think that if you can impact one person with your music, then it's pretty much worth it. — deadmau5 A FEW FACTS ABOUT DEADMAU5 ▶ Joel Zimmerman was born on January 5th, 1981 in Niagara Falls, Ontario. ▶ Joel started composing electronic music with the program “Impulse Tracker,” inspired largely by video game soundtracks. ▶ Joel created the alias deadmau5, and released his first full length album Get Scraped in 2005. ▶ Deadmau5 is the first EDM artist to be featured on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine. ▶ Deadmau5 has 3 Juno awards, 6 Grammy nominations, and 3 Billboard Dance Chart #1 hits. ▶ Deadmau5 has headlined Lollapalooza, Outside Lands, Sonar, Ultra, Electric Daisy Carnival, and Bonnaroo music festivals. v1.0 01 INTRODUCTION DEADMAU5 TEACHES ELECTRONIC MUSIC PRODUCTION 3 HOW TO USE THIS CLASS Before you dive in, we have a few recommendations for getting the most out of your experience. THINGS YOU MIGHT NEED To enjoy this class, you only need your computer and a desire to learn. However, here are a few other items we think will enhance your learning experience: CLASS WORKBOOK A This printable PDF filled with lesson recaps and assignments. SUGGESTED VIEWING SCHEDULE B Deadmau5 explains his techniques to you in 23 lessons. It’s tempting to finish all of the lessons in one sitting. We’d like to recommend our suggested viewing schedule, which you’ll find on page 5 of this Class Workbook. DEADMAU5'S MUSIC C A few of deadmau5's songs are mentioned repeatedly in the class: "Snowcone", "Imaginary Friends", "Phantoms Can't Hang", "Cat Thruster" and "No Problem". -

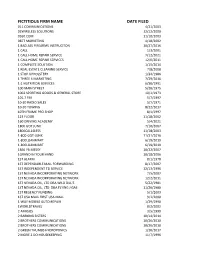

Fictitious Firm Name Date Filed

FICTITIOUS FIRM NAME DATE FILED 011 COMMUNICATIONS 4/21/2003 02WIRELESS SOLUTIONS 12/12/2000 0360.COM 11/18/2003 087T MARKETING 4/18/2002 1 BAD ASS FIREARMS INSTRUCITON 10/27/2016 1 CALL 1/3/2001 1 CALL HOME REPAIR SERVICE 7/12/2021 1 CALL HOME REPAIR SERVICES 12/6/2011 1 COMPLETE SOLUTION 1/15/2014 1 REAL ESTATE CLEANING SERVICE 7/8/2008 1 STOP UPHOLSTERY 1/24/1986 1 THREE 4 MARKETING 7/29/2016 1:1 NUTRITION SERVICES 6/30/1991 100 MAIN STREET 5/20/1975 1002 SPORTING GOODS & GENERAL STORE 10/1/1973 101.7 FM 5/7/1997 10-20 RADIO SALES 5/7/1971 10-20 TOWING 8/22/2017 10TH FRAME PRO SHOP 8/1/1997 123 FLOOR 11/18/2002 160 DRIVING ACADEMY 5/4/2021 1800 GOT JUNK 7/10/2007 1800CALL4LESS 11/18/2003 1-800-GOT-JUNK 11/21/2016 1-800LOANMART 6/19/2019 1-800LOANMART 6/19/2019 1866 YB MESSY 10/22/2007 1GRAND IN YOUR HAND 10/18/2006 1ST ALARM 8/1/1978 1ST DEPENDABLE MAIL FORWARDING 8/17/2007 1ST INDEPENDENT TD SERVICE 12/13/1996 1ST NEVADA INCORPORATING NETWORK 7/5/2007 1ST NEVADA INCORPORATING NETWORK 12/2/2011 1ST NEVADA OIL, LTD DBA WILD BILL'S 5/22/1981 1ST NEVADA OIL, LTD. DBA FLYING J GAS 11/20/1980 1ST REGENCY FUNDING 5/1/2003 1ST USA MALL FIRST USA MALL 9/1/2000 1-WAY MOBILE AUTO REPAIR 1/29/1990 1WORLDTRAVEL 8/2/2002 2 AMIGOS 3/5/1999 2 BARKING SISTERS 10/14/2014 2 BROTHERS COMMUNICATIONS 10/26/2010 2 BROTHERS COMMUNICATIONS 10/26/2010 2 GREEN THUMBS HYDROPONICS 1/26/2017 2 MORE 2 DO HOUSEKEEPING 11/7/1996 2 SECOND HAIR 6/12/2014 20 MINUTE SMILES 11/13/2009 20 MINUTES SMILES 11/4/2009 2020 30 TOURS 5/18/2020 2-10 HOME BUYERS WARRANTY 6/25/2014 -

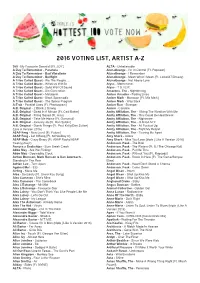

Artist A-Z, Triple J's 2016 Voting List

2016 VOTING LIST, ARTIST A-Z 360 - My Favourite Downfall {Ft. JOY.} ALTA - Unbelievable A Day To Remember - Paranoia AlunaGeorge - I'm In Control {Ft. Popcaan} A Day To Remember - Bad Vibrations AlunaGeorge - I Remember A Day To Remember - Bullfight AlunaGeorge - Mean What I Mean {Ft. Leikeli47/Dreezy} A Tribe Called Quest - We The People.... AlunaGeorge - Not Above Love A Tribe Called Quest - Whateva Will Be Alyss - Motherland A Tribe Called Quest - Solid Wall Of Sound Alyss - T S I E R A Tribe Called Quest - Dis Generation Amazons, The - Nightdriving A Tribe Called Quest - Melatonin Amber Arcades - Fading Lines A Tribe Called Quest - Black Spasmodic Amber Mark - Monsoon {Ft. Mia Mark} A Tribe Called Quest - The Space Program Amber Mark - Way Back A-Trak - Parallel Lines {Ft. Phantogram} Amber Run - Stranger A.B. Original - 2 Black 2 Strong Aminé - Caroline A.B. Original - Dead In A Minute {Ft. Caiti Baker} Amity Affliction, The - I Bring The Weather With Me A.B. Original - Firing Squad {Ft. Hau} Amity Affliction, The - This Could Be Heartbreak A.B. Original - Take Me Home {Ft. Gurrumul} Amity Affliction, The - Nightmare A.B. Original - January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - O.M.G.I.M.Y. A.B. Original - Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly/Dan Sultan} Amity Affliction, The - All Fucked Up {Live A Version 2016} Amity Affliction, The - Fight My Regret A$AP Ferg - New Level {Ft. Future} Amity Affliction, The - Tearing Me Apart A$AP Ferg - Let It Bang {Ft. ScHoolboy Q} Amy Shark - Adore A$AP Mob - Crazy Brazy {Ft. -

Song A-Z, Triple J's 2016 Voting List

2016 VOTING LIST, SONG A-Z 000000 - Midas.Gold Ain't No Rhyme - Jake Bugg 3 - Flume Ain't Too Far Gone - Harts 7 - Catfish And The Bottlemen Air - Allan Smithy 9 - Drake Air - KLP 24 - Hellions Airport Love - Jenny Broke The Window 25 - Hellions Alakazam ! - Justice 333 - Against Me! Alarm - Anne-Marie 1985 - Kvelertak Alaska - Maggie Rogers 1-5-9 - Koi Child Alchemy - Fractures (I Don't Wanna) Break Your Heart - Green Buzzard Algorytme - Lindstrom $$ Spoilers $$ - Jarrow Alien Anthem - Gabriella Cohen 1 In 100,000 - L-FRESH The LION Alihukwe - D.D Dumbo 10 d E A T h b R E a s T (Extended Version) - Bon Iver All At Once - Jack Carty 10 Feet Tall - Okenyo All For One - Stone Roses, The 100 Goosebumps - FEWS All Fucked Up - Amity Affliction, The 1000x {Ft. Broods} - Jarryd James All Lost - Jack Grace 16 Shots - Vic Mensa All Love - Drapht 1955 {Ft. Montaigne/Tom Thum} - Hilltop Hoods All Night - Crystal Fighters 1993 (No Chill) {Ft. Jess Kent} - Paces All Night {Ft. Dornik} - SG Lewis 2 Bad {Ft. Ddark} - Paragon All Night {Ft. Knox Fortune} - Chance The Rapper 2 Black 2 Strong - A.B. Original All Night Every Night - HOST 22 (OVER S∞∞N) [Bob Moose Extended Cab Version] - All Nite {Ft. Vince Staples} - Clams Casino Bon Iver All Or Nothing - Chrome Sparks 29 #Strafford APTS - Bon Iver All Things Good - Ivey 2B - Bonzai All Time Glow {Ft. Mathas} - Diger Rokwell 3 Rules - Tiga All We Do - Daniel Trakell 3 Wheel-Ups {Ft. Wiley/Giggs} - Kano All We Got {Ft. Kanye West/Chicago Children's Choir} - 3000 AD - Purling Hiss Chance The Rapper 32 Levels {Ft. -

VIBRANT and VITAL: the Economic Engine of Southeast Texas and Beyond

VOL. 47, NO. 1 | SUMMER 2019 VIBRANT AND VITAL: The Economic Engine of Southeast Texas and Beyond VIBRANT AND VITAL: | FROM THE PRESIDENT | CARDINAL CADENCE | IN THIS ISSUE | the magazine of lamar university The Economic Engine of VOL 47, NO. 1 | SUMMER 2019 Southeast Texas and Beyond amar University is proud of the impact we have within our 4 Science & Technology community of Southeast Texas and beyond. We are a socio- economic hub for our largely industrial-based area not wows at grand opening Through a rigorous curriculum, enriching Cardinal Cadence is published by Lamar University, Lonly with the thousands of career-ready graduates we produce a member of The Texas State University System extracurricular programs and abundant each year but also for the research our faculty and students and an affirmative action, equal opportunity 6 Faculty Profile: do that is timely and often locally-focused. LU also contributes educational institution. undergraduate research opportunities, as well as Jim Sanderson greatly to the arts within the region through the College of Fine Kate Downing, Executive Editor, Special internships and externships organized and managed Arts and Communication and the Center for the History and Assistant to the President and Director of Culture. This issue of Cadence concentrates on everything from Marketing Communications 8 Imagine it. Design it. by an attentive faculty, students are career and grad healthcare, banking and retail to restaurants and culture, along Cynthia Hicks ’89, ’93, Editor, Creative Director Build it. Improve it. school ready upon graduation—ready to compete, with faculty, staff and students who influence and connect LU to Daniel McLemore ’09, Associate Director of Marketing Communications the rest of our region, state, country and global community. -

February 13, 1992

James Madem-Uhiveisty THURSDAY FEBRUARY 13,1992 VOL 69, NO. 38 Applications to JMU still increasing Despite statewide decline, JMU received about 12,100 applications for 1992-V3 by Alan© Tempchm staffwriter The freshmen keep pQuring into JMU .. The number of freshman and transfer applications The number of applications received by JMU has risen steaMty in the past few to JMU continue to grow despite the decline in years and the number ofacceptances offeredluu risen proportwnatdy... \ * U77 graduating seniors in Virginia and the surrounding stales. The count for the number of freshman applications received before the admissions deadline of Feb. 1 has not been completed yet, but Director of Admissions Alan Cerveny estimates JMU has received about 12,100 freshman applications, up from 12,023 last year, and 2,000 transfer applications. 11302 Of these applicants, JMU plans to accept about 4,000 freshman students for a class of about 2,000 and will accept about 800 transfer students and XXX expect about 500 of these students to enroll. , t VO-Vl VhW 92- 93 GRANT JEWDINC/THE BREEZE ADMISSIONS page 2 Animal Rights Coalition protests circus performances to protest the treatment of animals in by Vince Rhodes circuses. staffwriter "We're trying to make people aware that animals Spectators got more than three rings of action are treated cruelly and that they deserve a better life when picketers joined the lions and acrobats at the than this," junior Laura Hilbert said. "They don't Convocation Center Tuesday for the Royal deserve to live their lives in cages being carted Hanneford Circus.