The Importance of Temporary Layoffs: an Empirical Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Non-Permanent Employment and Employees' Health in the Context Of

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Discussion Non-Permanent Employment and Employees’ Health in the Context of Sustainable HRM with a Focus on Poland Katarzyna Piwowar-Sulej * and Dominika B ˛ak-Grabowska Department of Labor, Capital and Innovation, Wroclaw University of Economics and Business, Komandorska 118/120, 53-345 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-503-129-991 Received: 8 June 2020; Accepted: 1 July 2020; Published: 7 July 2020 Abstract: This study is focused on the assumption that the analyses focused on sustainable human resource management (HRM) should include the problem of unstable forms of employment. Reference was also made to Poland, the country where the share of unstable forms of employment is the highest in the European Union. The authors based their findings on the literature and the data published, i.e., by Eurostat, OECD and Statistics Poland, accompanied by CSR reports. Insecure forms of employment have negative impact on employees’ health, primarily regarding their mental health. Statistically significant correlations were found between the expectation rate of possible job loss and non-standard employment variables, and the rate of reporting exposure to risk factors that affect mental wellbeing and precarious employment rates. However, conducting statistical analyses at the macro level is associated with limitations resulting from leaving out many important factors characteristic of the given countries and affecting the presented data. Current guidelines, relevant to reporting the use of non-standard forms of employment by enterprises, are inconsistent. Companies voluntarily demonstrate the scope of using non-permanent forms of employment and not referring to the issue of employees’ choice of a given type of employment and employees’ health. -

Kalleberg 2000 Nonstandard Employment Relations

Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-Time, Temporary and Contract Work Arne L. Kalleberg Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 26. (2000), pp. 341-365. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0360-0572%282000%2926%3C341%3ANERPTA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-N Annual Review of Sociology is currently published by Annual Reviews. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/annrevs.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mon Jan 21 22:38:28 2008 Annu. -

The Costs and Benefits of Flexible Employment for Working Mothers and Fathers

The Costs and Benefits of Flexible Employment for Working Mothers and Fathers Amanda Hosking Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of a Bachelor of Arts with Honours Degree School of Social Science The University of Queensland Submitted April 2004 This thesis represents original research undertaken for a Bachelor of Arts Honours Degree at the University of Queensland, and was undertaken between August 2003 and April 2004. The data used for this research comes from the Household Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey, which was funded by the Department of Family and Community Services (FaCS) and conducted by the Melbourne Institute for Economic and Social Research at the University of Melbourne. The research findings and interpretations presented in this thesis are my own and should not be attributed to FaCS, the Melbourne Institute or any other individual or group. Amanda Hosking Date ii Table of Contents The Costs and Benefits of Flexible Employment for Working Mothers and Fathers Title Page i Declaration ii Table of Contents iii List of Tables iv List of Figures iv List of Acronyms v Abstract vi Acknowledgements vii Chapter 1 - Introduction 1 Chapter 2 - Methodology 18 Chapter 3 - Results 41 Chapter 4 – Discussion and Conclusion 62 References 79 iii List of Tables Table 2.1: Employment Status, Employment Contract, Weekly Work Schedule and Daily Hours Schedule by Gender for Working Parents 26 Table 2.2: Construction of Occupation Variable from ASCO Major Groups 29 Table 2.3: Construction of Industry Variable -

The Effect of Wage Inequality on the Gender Pay

THE STRUCTURE OF THE PERMANENT JOB WAGE PREMIUM: EVIDENCE FROM EUROPE by Lawrence M. Kahn, Cornell University, CESifo, IZA, and NCER (Queensland) Email: [email protected] Postal Address: Cornell University 258 Ives Hall Ithaca, New York 14583 USA Phone: +607-255-0510 Fax: +607-255-4496 July 2013 Revised February 2014 * Preliminary draft. Comments welcome. The author is grateful to three anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions and to Alison Davies and Rhys Powell for their aid in acquiring the European Labour Force Survey regional unemployment rate data. This paper uses European Community Household Panel data (Users Database, waves 1-8, version of December 2003), supplied courtesy of the European Commission, Eurostat. Data are obtainable by application to Eurostat, which has no responsibility for the results and conclusions of this paper. 1 THE STRUCTURE OF THE PERMANENT JOB WAGE PREMIUM: EVIDENCE FROM EUROPE by Lawrence M. Kahn Abstract Using longitudinal data on individuals from the European Community Household Panel (ECHP) for thirteen countries during 1995-2001, I investigate the wage premium for permanent jobs relative to temporary jobs. The countries are Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. I find that among men the wage premium for a permanent vs. temporary job is lower for older workers and native born workers; for women, the permanent job wage premium is lower for older workers and those with longer job tenure. Moreover, there is some evidence that among immigrant men, the permanent job premium is especially high for those who migrated from outside the European Union. -

Termination of Permanent Employment Contract

Termination of permanent employment contract What you need to know : There are various conditions under which an employment contract can be terminated, either by the employee or by the employer, and specific rules are applicable to each situation. ◗ Resignation Information Initiated by the employee, this is not subject to any specific procedure but must be in accordance with the employee’s The employee must genuine and unequivocal wishes. Otherwise, it might be express his/her wishes in requalified as dismissal. writing and it is recom- mended to confirm receipt. Resignation does not have to be accepted or refused by the employer. The date of resignation marks the starting point of the notice period. ◗ Dismissal Sanction This is initiated by the employer and must be based on real Unjustified grounds for and justified reasons. It may include : dismissal may result in the payment of significant •Dismissal for personal reasons, based on a cause directly damages. pertaining to the employee, whether based on misconduct or not, •Dismissal for economic reasons not inherent in the employee Advice him/herself but justified by the company’s position. Dismissal for economic reasons may be individual or collective. Ask us before you start a dismissal ; the procedures Whatever the reason for the dismissal, the employer must are complex and specific to follow a strict procedure, which includes in particular : each type of dismissal. • Invitation to a preliminary interview, • Interview, •Delivery of dismissal letter, Information • Notice period, N.B.: some employees •Determination of severance pay. have special protection from In the event of a dispute, a settlement agreement may be dismissal. -

Understanding Nonstandard Work Arrangements: Using Research to Inform Practice

SHRM-SIOP Science of HR Series Understanding Nonstandard Work Arrangements: Using Research to Inform Practice Elizabeth George and Prithviraj Chattopadhyay Business School University of Auckland Copyright 2017 Society for Human Resource Management and Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of any agency of the U.S. government nor are they to be construed as legal advice. Elizabeth George is a professor of management in the Graduate School of Management at the University of Auckland. She has a Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin and has worked in universities in the United States, Australia and Hong Kong. Her research interests include nonstandard work arrangements and inequality in the workplace. Prithviraj Chattopadhyay is a professor of management in the Management and International Business Department at the University of Auckland. He received his Ph.D. in organization science from the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include diversity and demographic dissimilarity in organizations and nonstandard work arrangements. He has taught at universities in the United States, Australia and Hong Kong. 1 ABSTRACT This paper provides a literature review on nonstandard work arrangements with a goal of answering four key questions: (1) what are nonstandard work arrangements and how prevalent are they; (2) why do organizations have these arrangements; (3) what challenges do organizations that adopt these work arrangements face; and (4) how can organizations deal with these challenges? Nonstandard workers tend to be defined as those who are associated with organizations for a limited duration of time (e.g., temporary workers), work at a distance from the organization (e.g., remote workers) or are administratively distant from the organization (e.g., third-party contract workers). -

Women in Non-Standard Employmentpdf

INWORK Issue Brief No.9 Women in Non-standard Employment * Non-standard employment (NSE), including temporary employment, part-time and on-call work, multiparty employment arrangements, dependent and disguised self-employment, has become a contemporary feature of labour markets across the world. Its overall importance has increased over the past few decades, and its use has become more widespread across all economic sectors and occupations. However, NSE is not spread evenly across the labour market. Along with young people and migrants, women are often over-represented in non-standard arrangements. This policy brief examines the incidence of part-time and temporary work among women, discusses the reasons for their over-representation in these arrangements, and suggests policy solutions for alleviating gender inequalities with respect to NSE1. Women in part-time work Part-time employment (defined statistically as total employment, their share of all those working employees who work fewer than 35 hours per part-time is 57 per cent.2 Gender differences with week) is the most widespread type of non-standard respect to part-time hours are over 30 percentage employment found among women. In 2014, over 60 points in the Netherlands and Argentina. There is per cent of women worked part-time hours in the at least a 25 percentage point difference in Austria, Netherlands and India; over 50 per cent in Zimbabwe Belgium, Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Niger, Pakistan, and Mozambique; and over 40 per cent in a handful and Switzerland. of countries including Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Mali, Moreover, marginal part-time work – involving Malta, New Zealand, Niger, Switzerland, and United less than 15 hours per week – features particularly Kingdom (figure 1). -

DOL) Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC

U.S. Department of Labor Employment and Training Administration OFFICE OF FOREIGN LABOR CERTIFICATION COVID-19 Frequently Asked Questions ROUND 1 March 20, 2020 The U.S. Department of Labor's (DOL) Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC) remains fully operational during the federal government’s maximum telework flexibilities operating status – including the National Processing Centers (NPCs), PERM System, and Foreign Labor Application Gateway (FLAG) System. OFLC continues to process and issue prevailing wage determinations and labor certifications that meet all statutory and regulatory requirements. If employers are unable to meet all statutory and regulatory requirements, OFLC will not grant labor certification for the application. These frequently asked questions address impacts to OFLC operations and employers. 1. How will OFLC NPCs communicate with employers and their authorized attorneys or agents affected by the COVID-19 pandemic? Following standard operating procedures, OFLC will continue to contact employers and their authorized attorneys or agents primarily using email and - where email addresses are not available - will use U.S. mail. OFLC does not anticipate significant disruptions in its communications with employers and their authorized attorneys or agents in areas affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since email serves as a reliable form of communication to support the processing of applications for prevailing wage determinations and labor certification. Further, OFLC reminds stakeholders that email addresses used on applications must be the same as the email address regularly used by employers and, if applicable, their authorized attorneys or agents; specifically, the email address used to conduct their business operations and at which the employers and their authorized attorneys or agents are capable of sending and receiving electronic communications from OFLC related to the processing of applications. -

Information About Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff

Information about Unemployment Insurance for Workers on Temporary Layoff What is a Temporary Layoff? A temporary layoff occurs when you are partially unemployed because of lack of work or you have worked less than the equivalent of 3 customary, scheduled, full-time days for your plant or industry and earn less than your ineligible amount (earnings allowance plus your weekly benefit amount).Your employer will notify you when a temporary layoff occurs or is pending, and will prepare the information needed to file for temporary unemployment insurance benefits. Your employer is allowed to file a temporary layoff claim only once during your benefit year and this one occurrence is limited to a maximum of 6 consecutive weeks. The first week of this series is a waiting period week for which no benefits can be paid. After this six week period has passed (if you are still unemployed) you will need to file your own claim for unemployment benefits. What Happens Next? After your new claim is filed, you will be mailed Form N CUI-550, Wage Transcript and Monetary Determination. This form shows the employer(s) for whom you worked during the base period applicable to your claim, and the amount of wages they paid you during each quarter. It also shows the weekly amount of benefits payable to you and the number of weeks for which benefits may be paid during your benefit year. Currently, the maximum weekly benefit amount payable is $350 per week. The number of weeks payable at the full weekly benefit amount varies based on the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate. -

Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

SHRM Foundation’s Effective Practice Guidelines Series Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Sponsored by Right Management SHRM FOUNDAtion’S EFFECTIVE PraCTICE GUIDELINES SERIES Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives STRATEGIES FOR LONG-TERM SUCCESS Wayne F. Cascio Sponsored by Right Management Employment Downsizing and its Alternatives This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information regarding the subject matter covered. Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering legal or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent, licensed professional should be sought. Any federal and state laws discussed in this book are subject to frequent revision and interpretation by amendments or judicial revisions that may significantly affect employer or employee rights and obligations. Readers are encouraged to seek legal counsel regarding specific policies and practices in their organizations. This book is published by the SHRM Foundation, an affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM©). The interpretations, conclusions and recommendations in this book are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the SHRM Foundation. ©2009 SHRM Foundation. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the SHRM Foundation, 1800 Duke Street, Alexandria, VA 22314. The SHRM Foundation is the 501(c)3 nonprofit affiliate of the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). -

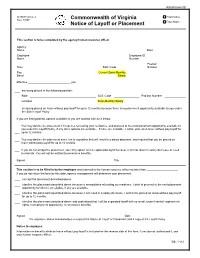

Notice of Layoff Or Reassignment

Attachment B DHRM Form L-1 First Notice Rev. 10/07 Commonwealth of Virginia Final Notice Notice of Layoff or Placement This section is to be completed by the agency human resource officer Agency Name Date Employee Employee ID Name Number Position Role SOC Code Number Pay Current Semi-Monthly Band Salary Effective , you are being placed in the following position: Role SOC Code Position Number Location Semi-Monthly Salary are being placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months because there is no placement opportunity available to you under the State Layoff Policy. If you are being placed, options available to you are marked with an X below. You may decline the placement if it requires relocating your residence, and proceed to the next placement opportunity available to you under the Layoff Policy, if any other options are available. If none are available, I will be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. You may decline the placement since it is to a position that will result in a salary decrease, and request that you be placed on leave without pay-layoff for up to 12 months. If you do not accept the placement, your only option is to be separated-layoff because it will not result in salary decrease or need to relocate. You will not be entitled to severance benefits. Signed Title This section is to be filled in by the employee and returned to the human resource officer no later than . If you do not return the form by this date, agency management will determine your placement. -

Women in the World of Work. Pending Challenges for Achieving Effective Equality in Latin America and the Caribbean.Thematic Labour Overview, 2019

5 5 THEMATIC Labour Women in the World of Work Pending Challenges for Achieving Effective Equality in Latin America and the Caribbean 5 Women in the World of Work Pending Challenges for Achieving Effective Equality in Latin America and the Caribbean Copyright © International Labour Organization 2019 First published 2019 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to ILO Publications (Rights and Licensing), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland, or by email: [email protected]. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered with a reproduction rights organ- ization may make copies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. Visit www.ifrro.org to find the reproduction rights organization in your country. ILO Women in the world of work. Pending Challenges for Achieving Effective Equality in Latin America and the Caribbean.Thematic Labour Overview, 2019. Lima: ILO / Regional Office for Latin America and the Caribbean, 2019. 188 p. Employment, labour market, gender, labour income, self-employment, equality, Latin America, Central America, Caribbean. ISSN: 2521-7437 (printed edition) ISSN: 2414-6021 (pdf web edition) ILO Cataloguing in Publication Data The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its author- ities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers.