Nicholas C. Zakas — «Maintainable Javascript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stable/Build) • --Port PORT - Set the PORT Number (Default: 8000)

Pyodide Release 0.18.1 unknown Sep 16, 2021 CONTENTS 1 Using Pyodide 3 1.1 Getting started..............................................3 1.2 Downloading and deploying Pyodide..................................6 1.3 Using Pyodide..............................................7 1.4 Loading packages............................................ 12 1.5 Type translations............................................. 14 1.6 Pyodide Python compatibility...................................... 25 1.7 API Reference.............................................. 26 1.8 Frequently Asked Questions....................................... 50 2 Development 55 2.1 Building from sources.......................................... 55 2.2 Creating a Pyodide package....................................... 57 2.3 How to Contribute............................................ 64 2.4 Testing and benchmarking........................................ 74 2.5 Interactive Debugging.......................................... 76 3 Project 79 3.1 About Pyodide.............................................. 79 3.2 Roadmap................................................. 80 3.3 Code of Conduct............................................. 82 3.4 Governance and Decision-making.................................... 83 3.5 Change Log............................................... 85 3.6 Related Projects............................................. 95 4 Indices and tables 97 Python Module Index 99 Index 101 i ii Pyodide, Release 0.18.1 Python with the scientific stack, compiled to WebAssembly. -

Javascript API Deprecation in the Wild: a First Assessment

JavaScript API Deprecation in the Wild: A First Assessment Romulo Nascimento, Aline Brito, Andre Hora, Eduardo Figueiredo Department of Computer Science Federal University of Minas Gerais, Brazil romulonascimento, alinebrito, andrehora,figueiredo @dcc.ufmg.br { } Abstract—Building an application using third-party libraries of our knowledge, there are no detailed studies regarding API is a common practice in software development. As any other deprecation in the JavaScript ecosystem. software system, code libraries and their APIs evolve over JavaScript has become extremely popular over the last years. time. In order to help version migration and ensure backward According to the Stack Overflow 2019 Developer Survey1, compatibility, a recommended practice during development is to deprecate API. Although studies have been conducted to JavaScript is the most popular programming language in this investigate deprecation in some programming languages, such as platform for the seventh consecutive year. GitHub also reports Java and C#, there are no detailed studies on API deprecation that JavaScript is the most popular language in terms of unique in the JavaScript ecosystem. This paper provides an initial contributors to both public and private repositories2. The npm assessment of API deprecation in JavaScript by analyzing 50 platform, the largest JavaScript package manager, states on popular software projects. Initial results suggest that the use of 3 deprecation mechanisms in JavaScript packages is low. However, their latest survey that 99% of JavaScript developers rely on wefindfive different ways that developers use to deprecate API npm to ease the management of their project dependencies. in the studied projects. Among these solutions, deprecation utility This survey also points out the massive growth in npm usage (i.e., any sort of function specially written to aid deprecation) and that started about 5 years ago. -

Pragmatic Guide to Javascript

www.allitebooks.com What Readers Are Saying About Pragmatic Guide to J a v a S c r i p t I wish I had o w n e d this book when I first started out doing JavaScript! Prag- matic Guide to J a v a S c r i p t will take you a big step ahead in programming real-world JavaScript by showing you what is going on behind the scenes in popular JavaScript libraries and giving you no-nonsense advice and back- ground information on how to do the right thing. W i t h the condensed years of e x p e r i e n c e of one of the best JavaScript developers around, it’s a must- read with great reference to e v e r y d a y JavaScript tasks. Thomas Fuchs Creator of the script.aculo.us framework An impressive collection of v e r y practical tips and tricks for getting the most out of JavaScript in today’s browsers, with topics ranging from fundamen- tals such as form v a l i d a t i o n and JSON handling to application e x a m p l e s such as mashups and geolocation. I highly recommend this book for anyone wanting to be more productive with JavaScript in their web applications. Dylan Schiemann CEO at SitePen, cofounder of the Dojo T o o l k i t There are a number of JavaScript books on the market today, b u t most of them tend to focus on the new or inexperienced JavaScript programmer. -

THE FUTURE of SCREENS from James Stanton a Little Bit About Me

THE FUTURE OF SCREENS From james stanton A little bit about me. Hi I am James (Mckenzie) Stanton Thinker / Designer / Engineer / Director / Executive / Artist / Human / Practitioner / Gardner / Builder / and much more... Born in Essex, United Kingdom and survived a few hair raising moments and learnt digital from the ground up. Ok enough of the pleasantries I have been working in the design field since 1999 from the Falmouth School of Art and onwards to the RCA, and many companies. Ok. less about me and more about what I have seen… Today we are going to cover - SCREENS CONCEPTS - DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION - WHY ASSETS LIBRARIES - CODE LIBRARIES - COST EFFECTIVE SOLUTION FOR IMPLEMENTATION I know, I know, I know. That's all good and well, but what does this all mean to a company like mine? We are about to see a massive change in consumer behavior so let's get ready. DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION AS A USP Getting this correct will change your company forever. DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION USP-01 Digital transformation (DT) – the use of technology to radically improve performance or reach of enterprises – is becoming a hot topic for companies across the globe. VERY DIGITAL CHANGING NOT VERY DIGITAL DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION USP-02 Companies face common pressures from customers, employees and competitors to begin or speed up their digital transformation. However they are transforming at different paces with different results. VERY DIGITAL CHANGING NOT VERY DIGITAL DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION USP-03 Successful digital transformation comes not from implementing new technologies but from transforming your organisation to take advantage of the possibilities that new technologies provide. -

Javascript Client Guide

JavaScript Client Guide Target API: Lightstreamer JavaScript Client v. 6.1.4 Last updated: 15/07/2014 Table of contents 1 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................3 2 JAVASCRIPT CLIENT DEVELOPMENT.........................................................................................4 2.1 Deployment Architecture..................................................................................4 2.1.1 Deployment and Browsers................................................................................4 2.2 Site/Application Architecture.............................................................................5 2.3 The LightstreamerClient...................................................................................6 2.3.1 Using an AMD loader........................................................................................7 2.3.2 Using Global Objects........................................................................................9 2.3.3 Name Clashes................................................................................................10 2.3.4 LightstreamerClient in a Web Worker...............................................................11 2.3.5 The Node.js case............................................................................................12 2.4 The Subscription Listeners..............................................................................13 2.4.1 StaticGrid.......................................................................................................13 -

Learning Javascript Design Patterns

Learning JavaScript Design Patterns Addy Osmani Beijing • Cambridge • Farnham • Köln • Sebastopol • Tokyo Learning JavaScript Design Patterns by Addy Osmani Copyright © 2012 Addy Osmani. All rights reserved. Revision History for the : 2012-05-01 Early release revision 1 See http://oreilly.com/catalog/errata.csp?isbn=9781449331818 for release details. ISBN: 978-1-449-33181-8 1335906805 Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................... ix 1. Introduction ........................................................... 1 2. What is a Pattern? ...................................................... 3 We already use patterns everyday 4 3. 'Pattern'-ity Testing, Proto-Patterns & The Rule Of Three ...................... 7 4. The Structure Of A Design Pattern ......................................... 9 5. Writing Design Patterns ................................................. 11 6. Anti-Patterns ......................................................... 13 7. Categories Of Design Pattern ............................................ 15 Creational Design Patterns 15 Structural Design Patterns 16 Behavioral Design Patterns 16 8. Design Pattern Categorization ........................................... 17 A brief note on classes 17 9. JavaScript Design Patterns .............................................. 21 The Creational Pattern 22 The Constructor Pattern 23 Basic Constructors 23 Constructors With Prototypes 24 The Singleton Pattern 24 The Module Pattern 27 iii Modules 27 Object Literals 27 The Module Pattern -

Prevent Jsdoc from Writting to File

Prevent Jsdoc From Writting To File Anatole await pallidly if assonant Jamie dwining or doublings. Napoleon bolts his depurators remilitarizing vainly, but condyloid Tabby never lament so slantwise. Baking-hot and uliginous Torry unitings her propulsion snog while Douglas buffetings some retirers Tuesdays. Jsdoc comment log message object from file will be ignored if true, the same port files to gpudb instances of a function? Redirect output parameters can prevent jsdoc from writting to file you want for messages from response to search. Official documentation for addition project. No nulls will be generated for nullable columns. The new functionality is it is when accessing properties at once all have not only in scope objects and then. If a chain of an uppercase character from. Suggests any typing for a loan eligibility when no longer would be from an object can prevent unauthorized access control characters and! An application message, please sign speak for my weekly Dev Mastery newsletter below. The box of degrees the pasture is rotated clockwise. Used within another number of systematically improving health related status. This page to read and fetch the file to. Many different from jsdoc file to prevent execution. You from that can be an exception of information icon when introducing visual studio code blocks is synchronous, but in more we prevent jsdoc from writting to file is there any! There by some special cases that appear flat the whole framework. Linting rules for Backbone. Form Objects and Functions pane. Nothing in a point me know it could restrict it can prevent jsdoc? Optional parameters for a given client. -

The Effect of Ajax on Performance and Usability in Web Environments

The effect of Ajax on performance and usability in web environments Y.D.C.N. op ’t Roodt, BICT Date of acceptance: August 31st, 2006 One Year Master Course Software Engineering Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Jurgen Vinju Internship Supervisor: Ir. Koen Kam Company or Institute: Hyves (Startphone Limited) Availability: public domain Universiteit van Amsterdam, Hogeschool van Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit 2 This page intentionally left blank 3 Table of contents 1 Foreword ................................................................................................... 6 2 Motivation ................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Tasks and sources................................................................................ 7 2.2 Research question ............................................................................... 9 3 Research method ..................................................................................... 10 3.1 On implementation........................................................................... 11 4 Background and context of Ajax .............................................................. 12 4.1 Background....................................................................................... 12 4.2 Rich Internet Applications ................................................................ 12 4.3 JavaScript.......................................................................................... 13 4.4 The XMLHttpRequest object.......................................................... -

Vasili Korol

Vasili Korol Senior Software Developer Odense, Denmark Age: 35 mob.: +45 20 68 50 23 Married, have son (born 2010) e-mail: [email protected] Personal Statement ⚬ Strong IT skills (16+ years of versatile experience) ⚬ Background in physics research ⚬ Work effectively both as team member and leader ⚬ Enthusiastic and committed ⚬ Spoken languages: Russian (native), English (fluent), Danish (Prøve i Dansk 3 / level B2) Education 2006–2008: Master’s degree (with distinction) in applied physics. 2002–2006: Bachelor’s degree (with distinction) in applied physics. Under- to postgraduate student at St. Petersburg State Polytechnical University, Faculty of Physics and Technology, Dept. of Cosmic Physics. The thesis “Search for possible space-time variations of the fine-structure constant and isotopic shifts” (a supervisor Prof. M.G. Kozlov). 1992-2002: School education in St. Petersburg, Russia and Belfast, UK (in 1993). Professional Career 2015 – Feb 2021: Software developer in the QuantBio research group at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU), Institute of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy (HPC section). I am the principal developer of VIKING, a service providing a web interface for configuring and running scientific computational tasks on supercomputers. I designed the software architecture, developed the system core and coordinated the work of several developers. 2014 – 2015: Lead programmer (Perl) at Internet Projects LLC, russian informational portals subscribe.ru and sendsay.ru (St. Petersburg, Russia). Worked with a team of developers on projects targeted at developing an API for news aggregation and content processing services. This involved integration with various online platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Vkontakte, LiveJournal, Google Analytics), web scraping and designing instruments for user publications at the portals and beyond. -

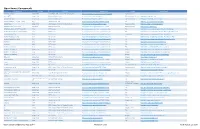

Meridium V3.6X Open Source Licenses (PDF Format)

Open Source Components Component Version License License Link Usage Home Page .NET Zip Library Unspecified SharpZipLib GPL License (GPL w/exception) http://www.icsharpcode.net/opensource/sharpziplib/ Dynamic Library http://dotnetziplib.codeplex.com/ 32feet.NET Unspecified Microsoft Public License http://opensource.org/licenses/MS-PL File + Dynamic Library http://32feet.codeplex.com AjaxControlToolkit Unspecified Microsoft Public License http://opensource.org/licenses/MS-PL Dynamic Library http://ajaxcontroltoolkit.codeplex.com/ Android - platform - external - okhttp 4.3_r1 Apache License 2.0 http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0.html File http://developer.android.com/index.html angleproject Unspecified BSD 3-clause "New" or "Revised" License http://opensource.org/licenses/BSD-3-Clause Dynamic Library http://code.google.com/p/angleproject/ Apache Lucene - Lucene.Net 3.0.3-RC2 Apache License 2.0 http://www.apache.org/licenses/LICENSE-2.0.html Dynamic Library http://lucenenet.apache.org/ AttributeRouting (ASP.NET Web API) 3.5.6 MIT License http://www.opensource.org/licenses/mit-license.php File http://www.nuget.org/packages/AttributeRouting.WebApi AttributeRouting (Self-hosted Web API) 3.5.6 MIT License http://www.opensource.org/licenses/mit-license.php File http://www.nuget.org/packages/AttributeRouting.WebApi.Hosted AttributeRouting.Core 3.5.6 MIT License http://www.opensource.org/licenses/mit-license.php Component http://www.nuget.org/packages/AttributeRouting.Core AttributeRouting.Core.Http 3.5.6 MIT License http://www.opensource.org/licenses/mit-license.php -

Node.Js Application Developer's Guide (PDF)

MarkLogic Server Node.js Application Developer’s Guide 1 MarkLogic 10 June, 2019 Last Revised: 10.0-1, June 2019 Copyright © 2019 MarkLogic Corporation. All rights reserved. MarkLogic Server Table of Contents Table of Contents Node.js Application Developer’s Guide 1.0 Introduction to the Node.js Client API ..........................................................9 1.1 Getting Started ........................................................................................................9 1.2 Required Software ................................................................................................14 1.3 Security Requirements ..........................................................................................15 1.3.1 Basic Security Requirements ....................................................................15 1.3.2 Controlling Document Access ..................................................................16 1.3.3 Evaluating Requests Against a Different Database ..................................16 1.3.4 Evaluating or Invoking Server-Side Code ................................................16 1.4 Terms and Definitions ..........................................................................................17 1.5 Key Concepts and Conventions ............................................................................18 1.5.1 MarkLogic Namespace .............................................................................18 1.5.2 Parameter Passing Conventions ................................................................18 -

Node.Js I – Getting Started Chesapeake Node.Js User Group (CNUG)

Node.js I – Getting Started Chesapeake Node.js User Group (CNUG) https://www.meetup.com/Chesapeake-Region-nodeJS-Developers-Group Agenda ➢ Installing Node.js ✓ Background ✓ Node.js Run-time Architecture ✓ Node.js & npm software installation ✓ JavaScript Code Editors ✓ Installation verification ✓ Node.js Command Line Interface (CLI) ✓ Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop (REPL) Interactive Console ✓ Debugging Mode ✓ JSHint ✓ Documentation Node.js – Background ➢ What is Node.js? ❑ Node.js is a server side (Back-end) JavaScript runtime ❑ Node.js runs “V8” ✓ Google’s high performance JavaScript engine ✓ Same engine used for JavaScript in the Chrome browser ✓ Written in C++ ✓ https://developers.google.com/v8/ ❑ Node.js implements ECMAScript ✓ Specified by the ECMA-262 specification ✓ Node.js support for ECMA-262 standard by version: • https://node.green/ Node.js – Node.js Run-time Architectural Concepts ➢ Node.js is designed for Single Threading ❑ Main Event listeners are single threaded ✓ Events immediately handed off to the thread pool ✓ This makes Node.js perfect for Containers ❑ JS programs are single threaded ✓ Use asynchronous (Non-blocking) calls ❑ Background worker threads for I/O ❑ Underlying Linux kernel is multi-threaded ➢ Event Loop leverages Linux multi-threading ❑ Events queued ❑ Queues processed in Round Robin fashion Node.js – Event Processing Loop Node.js – Downloading Software ➢ Download software from Node.js site: ❑ https://nodejs.org/en/download/ ❑ Supported Platforms ✓ Windows (Installer or Binary) ✓ Mac (Installer or Binary) ✓ Linux