On Affect and Criticality in Steve Mcqueen's Widows JUMP

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Racing Is Life. Anything Before Or After Is Just Waiting.'

Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso recently went under the hammer at Christie’s in Monterey, offering another reminder of a man whose motoring exploits mirrored some of his most famous onscreen performances. Christopher Kanal pays tribute to a legendary car driven by a screen icon. Thegetaway n 16 August 2007, Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta McQueen was also an avid racing enthusiast, performing many of his Lusso went under the hammer at Christies. This remarkable car was own stunts, and at one time considered becoming a professional racing Obought by an anonymous owner, who placed his bid by phone, for driver. Two weeks after breaking an ankle in one bike race, he and co-driver a cool $2.31 million – nearly twice the estimated pre-sale price. The auction Peter Revson raced a Porsche 908/02 in the 12 Hours of Sebring, winning drew 800 people to the Monterey Jet Center in California and attracted their engine class and finishing second to Mario Andretti’s Ferrari by a spirited bidding according to Christie’s Rik Pike. margin of just 23 seconds. So begins another chapter in the life of one of McQueen’s favourite cars, which he drove for nearly a decade. McQueen’s Lusso inspires an almost fetish- like fascination, created from a potent blend of McQueen mythology and an ‘racing IS LIFE. insatiable desire for limited-edition 12-cylinder Ferraris. McQueen is dead 27 years but his iconic status has never been more assured. The Lusso is widely ANYTHING BEFORE acknowledged as Ferrari’s greatest aesthetic and engineering achievement. -

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve Mcqueen”, the New Journal and Guide, February 03, 2014

Kam Williams, “The “12 Years a Slave” Interview: Steve McQueen”, The new journal and guide, February 03, 2014 Artist and filmmaker Steven Rodney McQueen was born in London on October 9, 1969. His critically-acclaimed directorial debut, Hunger, won the Camera d’Or at the 2008 Cannes Film Festival. He followed that up with the incendiary offering Shame, a well- received, thought-provoking drama about addiction and secrecy in the modern world. In 1996, McQueen was the recipient of an ICA Futures Award. A couple of years later, he won a DAAD artist’s scholarship to Berlin. Besides exhibiting at the ICA and at the Kunsthalle in Zürich, he also won the coveted Turner Prize. He has exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago, the Musee d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Documenta, and at the 53rd Venice Biennale as a representative of Great Britain. His artwork can be found in museum collections around the world like the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Centre Pompidou. In 2003, he was appointed Official War Artist for the Iraq War by the Imperial War Museum and he subsequently produced the poignant and controversial project Queen and Country commemorating the deaths of British soldiers who perished in the conflict by presenting their portraits as a sheet of stamps. Steve and his wife, cultural critic Bianca Stigter, live and work in Amsterdam which is where they are raising their son, Dexter, and daughter, Alex. Here, he talks about his latest film, 12 Years a Slave, which has been nominated for 9 Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. -

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

Two Years Ago, Found Was Steve Mcqueen's Iconic 1968 Ford Mustang GT

Two years ago, found was Steve McQueen's iconic 1968 Ford Mustang GT. Only traces of its original highland green paint job remained as it had sat unnoticed in a backyard in Mexico for years. Collectors had been searching for it for decades. Of course, this is not just any old '68 Stang. This was one of the original cars used in the classic Steve McQueen film "Bullitt," a film that defined "cool" for a generation of Americans. McQueen was Hollywood's "King of Cool" for a reason. In his role as the detective Frank Bullitt, he literally flies his car through the streets of San Francisco in what is regarded by many as the greatest car chase scene in cinematic history. Steve McQueen was not cool because he drove the Bullitt car. The Bullitt car was cool because Steve McQueen drove it. At the time, Steve McQueen was the number-one movie star in the world, and he is still used as a point of reference for masculinity and "coolness" to this day. He was (and is) the definition of an American icon. Yet, until late in his life he struggled to find meaning in life, and he suffered because of it. It might have been because he was born into a home of an alcoholic mother and a father that left him early in life, but eventually he found himself on the wrong side of the law more than once. He was arrested several times as a teen and sent to truancy homes for rebellious kids. He served in the Marine Corps, where he demonstrated both valor and rebellion. -

Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South

Antoni Górny Appalling! Terrifying! Wonderful! Blaxploitation and the Cinematic Image of the South Abstract: The so-called blaxploitation genre – a brand of 1970s film-making designed to engage young Black urban viewers – has become synonymous with channeling the political energy of Black Power into larger-than-life Black characters beating “the [White] Man” in real-life urban settings. In spite of their urban focus, however, blaxploitation films repeatedly referenced an idea of the South whose origins lie in antebellum abolitionist propaganda. Developed across the history of American film, this idea became entangled in the post-war era with the Civil Rights struggle by way of the “race problem” film, which identified the South as “racist country,” the privileged site of “racial” injustice as social pathology.1 Recently revived in the widely acclaimed works of Quentin Tarantino (Django Unchained) and Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave), the two modes of depicting the South put forth in blaxploitation and the “race problem” film continue to hold sway to this day. Yet, while the latter remains indelibly linked, even in this revised perspective, to the abolitionist vision of emancipation as the result of a struggle between idealized, plaintive Blacks and pathological, racist Whites, blaxploitation’s troping of the South as the fulfillment of grotesque White “racial” fantasies offers a more powerful and transformative means of addressing America’s “race problem.” Keywords: blaxploitation, American film, race and racism, slavery, abolitionism The year 2013 was a momentous one for “racial” imagery in Hollywood films. Around the turn of the year, Quentin Tarantino released Django Unchained, a sardonic action- film fantasy about an African slave winning back freedom – and his wife – from the hands of White slave-owners in the antebellum Deep South. -

Film Suggestions to Celebrate Black History

Aurora Film Circuit I do apologize that I do not have any Canadian Films listed but also wanted to provide a list of films selected by the National Film Board that portray the multi-layered lives of Canada’s diverse Black communities. Explore the NFB’s collection of films by distinguished Black filmmakers, creators, and allies. (Link below) Black Communities in Canada: A Rich History - NFB Film Info – data gathered from TIFF or IMBd AFC Input – Personal review of the film (Nelia Pacheco Chair/Programmer, AFC) Synopsis – this info was gathered from different sources such as; TIFF, IMBd, Film Reviews etc. FILM TITEL and INFO AFC Input SYNOPSIS FILM SUGGESTIONS TO CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH SMALL AXE I am very biased towards the Director Small Axe is based on the real-life experiences of London's West Director: Steve McQueen Steve McQueen, his films are very Indian community and is set between 1969 and 1982 UK, 2020 personal and gorgeous to watch. I 1st – MANGROVE 2hr 7min: English cannot recommend this series Mangrove tells this true story of The Mangrove Nine, who 5 Part Series: ENOUGH, it was fantastic and the clashed with London police in 1970. The trial that followed was stories are a must see. After listening to the first judicial acknowledgment of behaviour motivated by Principal Cast: Gary Beadle, John Boyega, interviews/discussions with Steve racial hatred within the Metropolitan Police Sheyi Cole Kenyah Sandy, Amarah-Jae St. McQueen about this project you see his 2nd – LOVERS ROCK 1hr 10 min: Aubyn and many more.., A single evening at a house party in 1980s West London sets the passion and what this production meant to him, it is a series of “love letters” to his scene, developing intertwined relationships against a Category: TV Mini background of violence, romance and music. -

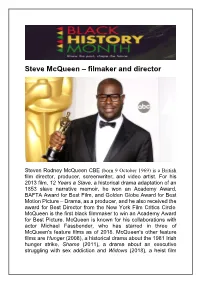

Steve Mcqueen – Filmaker and Director

Steve McQueen – filmaker and director Steven Rodney McQueen CBE (born 9 October 1969) is a British film director, producer, screenwriter, and video artist. For his 2013 film, 12 Years a Slave, a historical drama adaptation of an 1853 slave narrative memoir, he won an Academy Award, BAFTA Award for Best Film, and Golden Globe Award for Best Motion Picture – Drama, as a producer, and he also received the award for Best Director from the New York Film Critics Circle. McQueen is the first black filmmaker to win an Academy Award for Best Picture. McQueen is known for his collaborations with actor Michael Fassbender, who has starred in three of McQueen's feature films as of 2018. McQueen's other feature films are Hunger (2008), a historical drama about the 1981 Irish hunger strike, Shame (2011), a drama about an executive struggling with sex addiction and Widows (2018), a heist film about a group of women who vow to finish the job when their husbands die attempting to do so. McQueen was born in London and is of Grenadianand Trinidadian descent. He grew up in Hanwell, West London and went to Drayton Manor High School. In a 2014 interview, McQueen stated that he had a very bad experience in school, where he had been placed into a class for students believed best suited "for manual labour, more plumbers and builders, stuff like that." Later, the new head of the school would admit that there had been "institutional" racism at the time. McQueen added that he was dyslexic and had to wear an eyepatch due to a lazy eye, and reflected this may be why he was "put to one side very quickly". -

BFI Poll Reveals UK's Favourite Black Star Performance

BFI POLL REVEALS UK’S FAVOURITE BLACK STAR PERFORMANCE: SIDNEY POITIER AS “MISTER TIBBS” In the Heat of the Night Angela Bassett’s courageous portrayal of Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It voted as top performance by over 100 industry experts London: (embargoed until 16:30 BST) Thursday 20 October, 2016 – To mark this week’s official launch of its BLACK STAR season, the BFI announced today that Sidney Poitier’s critically-acclaimed and seminal performance as Detective Virgil Tibbs in In the Heat of the Night (dir. Norman Jewison, 1967) has been voted the public’s Favourite Black Star Performance in a poll which included 100 performances spanning over 80 years in film and TV. Running alongside the public poll, a separate poll of over 100 industry experts voted for Angela Bassett’s Oscar®- nominated performance as Tina Turner in What’s Love Got to Do with It (dir. Brian Gibson, 1993). UK Public Poll Pam Grier followed in second place with her terrific turn as the titular character in Quentin Tarantino’s Jackie Brown – an homage to the 1970’s era of Blaxploitation films in America; Michael K. Williams was number three with his unforgettable portrayal of the legendary Omar Little, the openly gay, notorious stick-up man with a strict moral code feared by drug dealers across the city of Baltimore, in the socially and politically charged hit television series The Wire. British actor Chiwetel Ejiofor followed in fourth with his visceral portrayal of Solomon Northup, his break-out performance in Steve McQueen’s ground-breaking, Oscar®-winning true story, 12 Years A Slave; and Morgan Freeman rounded out the top five with his acclaimed, quiet and layered performance in Frank Darabont’s Oscar®-nominated cult classic, The Shawshank Redemption. -

Widescreen Weekend 2008 Brochure (PDF)

A5 Booklet_08:Layout 1 28/1/08 15:56 Page 41 THIS IS CINERAMA Friday 7 March Dirs. Merian C. Cooper, Michael Todd, Fred Rickey USA 1952 120 mins (U) The first 3-strip film made. This is the original Cinerama feature The Widescreen Weekend continues to welcome all which launched the widescreen those fans of large format and widescreen films – era, and is about as fun a piece of CinemaScope, VistaVision, 70mm, Cinerama and IMAX – Americana as you are ever likely and presents an array of past classics from the vaults of to see. More than a technological curio, it's a document of its era. the National Media Museum. A weekend to wallow in the nostalgic best of cinema. HAMLET (70mm) Sunday 9 March Widescreen Passes £70 / £45 Dir. Kenneth Branagh GB/USA 1996 242 mins (PG) Available from the box office 0870 70 10 200 Kenneth Branagh, Julie Christie, Derek Jacobi, Kate Winslet, Judi Patrons should note that tickets for 2001: A Space Odyssey are priced Dench, Charlton Heston at £10 or £7.50 concessions Anyone who has seen this Hamlet in 70mm knows there is no better-looking version in colour. The greatest of Kenneth Branagh’s many achievements so 61 far, he boldly presents the full text of Hamlet with an amazing cast of actors. STAR! (70mm) Saturday 8 March Dir. Robert Wise USA 1968 174 mins (U) Julie Andrews, Daniel Massey, Richard Crenna, Jenny Agutter Robert Wise followed his box office hits West Side Story and The Sound of Music with Star! Julie 62 63 Andrews returned to the screen as Gertrude Lawrence and the film charts her rise from the music hall to Broadway stardom. -

Hanks, Spielberg Tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood Poll

Hanks, Spielberg tops in U.S. Army Europe Hollywood poll June 8, 2011 By U.S. Army Europe Public Affairs HEIDELBERG, Germany -- “Band of Brothers” narrowly edged “Saving Private Ryan” in a two-week U.S. Army Europe Web poll asking the public to select their five favorite Related Links films portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. Poll Results The final tally for the top spot was 128 votes to 126, revealing the powerful appeal Tom U.S. Army Europe Facebook Hanks and Steven Spielberg hold among poll participants in detailing the experiences of U.S. Army Europe Twitter WWII veterans. U.S. Army Europe YouTube The two movies were both the result of collaborations by the Hollywood A-listers. U.S. Army Europe Flickr Rounding out the top five was “The Longest Day,” a 1962 drama starring John Wayne about the events of D-Day; “Patton,” directed by Francis Ford Coppola in 1970 and starring George C. Scott as the famed American general; and “A Bridge Too Far,” a 1977 film starring Sean Connery about the failed Operation Market- Garden. The poll received a total of 814 votes and was based on the realism, entertainment value and overall quality of 20 movies featuring the U.S. Army in Europe. Some of Hollywood's biggest stars throughout history - Elvis, Clint Eastwood, Gary Cooper, Bill Murray, Gene Hackman – have all taken turns on the big screen portraying U.S. Soldiers in Europe. But to participants of the U.S. Army Europe poll, it was the lesser-known “Band of Brothers” in Easy Company who were most endearing. -

The Statement

THE STATEMENT A Robert Lantos Production A Norman Jewison Film Written by Ronald Harwood Starring Michael Caine Tilda Swinton Jeremy Northam Based on the Novel by Brian Moore A Sony Pictures Classics Release 120 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS SHANNON TREUSCH MELODY KORENBROT CARMELO PIRRONE ERIN BRUCE ZIGGY KOZLOWSKI ANGELA GRESHAM 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, 550 MADISON AVENUE, SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 8TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 NEW YORK, NY 10022 PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com THE STATEMENT A ROBERT LANTOS PRODUCTION A NORMAN JEWISON FILM Directed by NORMAN JEWISON Produced by ROBERT LANTOS NORMAN JEWISON Screenplay by RONALD HARWOOD Based on the novel by BRIAN MOORE Director of Photography KEVIN JEWISON Production Designer JEAN RABASSE Edited by STEPHEN RIVKIN, A.C.E. ANDREW S. EISEN Music by NORMAND CORBEIL Costume Designer CARINE SARFATI Casting by NINA GOLD Co-Producers SANDRA CUNNINGHAM YANNICK BERNARD ROBYN SLOVO Executive Producers DAVID M. THOMPSON MARK MUSSELMAN JASON PIETTE MICHAEL COWAN Associate Producer JULIA ROSENBERG a SERENDIPITY POINT FILMS ODESSA FILMS COMPANY PICTURES co-production in association with ASTRAL MEDIA in association with TELEFILM CANADA in association with CORUS ENTERTAINMENT in association with MOVISION in association with SONY PICTURES -

Actress Carey Mulligan to Receive the Artistic Achievement Award During the Centerpiece Presentation of Wildlife Costume Desi

Media Contact: Nick Harkin / Matthew Bryant Carol Fox and Associates 773.969.5033 / 773.969.5034 [email protected] [email protected] For Immediate Release: Sept. 12, 2018 ACTRESS CAREY MULLIGAN TO RECEIVE THE ARTISTIC ACHIEVEMENT AWARD DURING THE CENTERPIECE PRESENTATION OF WILDLIFE COSTUME DESIGNER RUTH CARTER (BLACK PANTHER, SELMA) TO BE HONORED WITH A CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT THIS YEAR’S BLACK PERSPECTIVES TRIBUTE The Festival will also pay tribute to the legacy of actress and Festival co-founder Colleen Moore and Chicago graphic artist Art Paul th CHICAGO – The 54 Chicago International Film Festival, presented by Cinema/Chicago, today announced Tributes to actress Carey Mulligan in conjunction with this year’s Centerpiece film Wildlife, and costume designer Ruth Carter as part of the Festival’s annual Black Perspectives Program. The Festival will also celebrate posthumously two artists special to Chicago, graphic designer Art Paul in conjunction with a screening of Jennifer Kwong’s Art Paul of Playboy: The Man Behind the Bunny, and actress and Chicago International Film Festival co-founder Colleen Moore, with a screening of The Power and the Glory (1933). The tributes will take place over the course of the Festival’s 12-day run at AMC River East 21 (322 E. Illinois St.) in Chicago, October 10-21, 2018. British actress Carey Mulligan is one of the paramount talents of her generation. Nominated for an Oscar®, a Golden Globe, and a SAG award for her radiant portrayal of the innocent teenage Jenny in An Education, Mulligan has delivered captivating performances across stage and screen, including Shame, The Great Gatsby, Inside Llewyn Davis, Mudbound, and this year’s Festival selection, Wildlife.