Castilleja in Utah, by David E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary of Offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019

Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 3841 Number of items in BX 301 thru BX 463 1815 Number of unique text strings used as taxa 990 Taxa offered as bulbs 1056 Taxa offered as seeds 308 Number of genera This does not include the SXs. Top 20 Most Oft Listed: BULBS Times listed SEEDS Times listed Oxalis obtusa 53 Zephyranthes primulina 20 Oxalis flava 36 Rhodophiala bifida 14 Oxalis hirta 25 Habranthus tubispathus 13 Oxalis bowiei 22 Moraea villosa 13 Ferraria crispa 20 Veltheimia bracteata 13 Oxalis sp. 20 Clivia miniata 12 Oxalis purpurea 18 Zephyranthes drummondii 12 Lachenalia mutabilis 17 Zephyranthes reginae 11 Moraea sp. 17 Amaryllis belladonna 10 Amaryllis belladonna 14 Calochortus venustus 10 Oxalis luteola 14 Zephyranthes fosteri 10 Albuca sp. 13 Calochortus luteus 9 Moraea villosa 13 Crinum bulbispermum 9 Oxalis caprina 13 Habranthus robustus 9 Oxalis imbricata 12 Haemanthus albiflos 9 Oxalis namaquana 12 Nerine bowdenii 9 Oxalis engleriana 11 Cyclamen graecum 8 Oxalis melanosticta 'Ken Aslet'11 Fritillaria affinis 8 Moraea ciliata 10 Habranthus brachyandrus 8 Oxalis commutata 10 Zephyranthes 'Pink Beauty' 8 Summary of offerings in the PBS Bulb Exchange, Dec 2012- Nov 2019 Most taxa specify to species level. 34 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for bulbs 23 taxa were listed as Genus sp. for seeds 141 taxa were listed with quoted 'Variety' Top 20 Most often listed Genera BULBS SEEDS Genus N items BXs Genus N items BXs Oxalis 450 64 Zephyranthes 202 35 Lachenalia 125 47 Calochortus 94 15 Moraea 99 31 Moraea -

Boophone Disticha

Micropropagation and pharmacological evaluation of Boophone disticha Lee Cheesman Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research Centre for Plant Growth and Development School of Life Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg April 2013 COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE, ENGINEERING AND SCIENCES DECLARATION 1 – PLAGIARISM I, LEE CHEESMAN Student Number: 203502173 declare that: 1. The research contained in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my original research. 2. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other University. 3. This thesis does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. 4. This thesis does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a. Their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced. b. Where their exact words have been used, then their writing has been placed in italics and inside quotation marks, and referenced. 5. This thesis does not contain text, graphics or tables copied and pasted from the internet, unless specifically acknowledged, and the source being detailed in the thesis and in the reference section. Signed at………………………………....on the.....….. day of ……......……….2013 ______________________________ SIGNATURE i STUDENT DECLARATION Micropropagation and pharmacological evaluation of Boophone disticha I, LEE CHEESMAN Student Number: 203502173 declare that: 1. The research reported in this dissertation, except where otherwise indicated is the result of my own endeavours in the Research Centre for Plant Growth and Development, School of Life Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg. -

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies concolor var. concolor White fir Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica Corkbark fir Devender, T. R. (2005) Abronia villosa Hariy sand verbena McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon abutiloides Shrubby Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon berlandieri Berlandier Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon incanum Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon malacum Yellow Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon mollicomum Sonoran Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon palmeri Palmer Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon parishii Pima Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon parvulum Dwarf Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium Abutilon pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon reventum Yellow flower Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia angustissima Whiteball acacia Devender, T. R. (2005); DBGH McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia constricta Whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia greggii Catclaw acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) Acacia millefolia Santa Rita acacia McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia neovernicosa Chihuahuan whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Acalypha lindheimeri Shrubby copperleaf Herbarium Acalypha neomexicana New Mexico copperleaf McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acalypha ostryaefolia McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acalypha pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acamptopappus McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Rayless goldenhead sphaerocephalus Herbarium Acer glabrum Douglas maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer grandidentatum Sugar maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer negundo Ashleaf maple McLaughlin, S. -

Plant Species of Special Concern and Vascular Plant Flora of the National

Plant Species of Special Concern and Vascular Plant Flora of the National Elk Refuge Prepared for the US Fish and Wildlife Service National Elk Refuge By Walter Fertig Wyoming Natural Diversity Database The Nature Conservancy 1604 Grand Avenue Laramie, WY 82070 February 28, 1998 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following individuals for their assistance with this project: Jim Ozenberger, ecologist with the Jackson Ranger District of Bridger-Teton National Forest, for guiding me in his canoe on Flat Creek and for providing aerial photographs and lodging; Jennifer Whipple, Yellowstone National Park botanist, for field assistance and help with field identification of rare Carex species; Dr. David Cooper of Colorado State University, for sharing field information from his 1994 studies; Dr. Ron Hartman and Ernie Nelson of the Rocky Mountain Herbarium, for providing access to unmounted collections by Michele Potkin and others from the National Elk Refuge; Dr. Anton Reznicek of the University of Michigan, for confirming the identification of several problematic Carex specimens; Dr. Robert Dorn for confirming the identification of several vegetative Salix specimens; and lastly Bruce Smith and the staff of the National Elk Refuge for providing funding and logistical support and for allowing me free rein to roam the refuge for plants. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction . 6 Study Area . 6 Methods . 8 Results . 10 Vascular Plant Flora of the National Elk Refuge . 10 Plant Species of Special Concern . 10 Species Summaries . 23 Aster borealis . 24 Astragalus terminalis . 26 Carex buxbaumii . 28 Carex parryana var. parryana . 30 Carex sartwellii . 32 Carex scirpoidea var. scirpiformis . -

Plants of Witcher Meadow Area, Inyo National Forest California Native Plant Society Bristlecone Chapter

Plants of Witcher Meadow Area, Inyo National Forest California Native Plant Society Bristlecone Chapter PTERIDOPHYTES (Ferns and Allies) EQUISETACEAE - Horsetail Family Equisetum arvense Common horsetail E. laevigatum Smooth scouring rush GYMNOSPERMS (Coniferous Plants) CUPRESSACEAE - Cypress Family Juniperus grandis (J. occidentalis v. australis) Mountain juniper EPHEDRACEAE - Ephedra family Ephedra viridis Green ephedra PINACEAE - Pine Family Pinus jeffreyi Jeffrey pine P. monophylla Single-leaf pinyon pine ANGIOSPERMS (Flowering Plants) APIACEAE - Carrot Family Cymopterus aborginum White cymopteris APOCYNACEAE - Dogbane Family Apocynum cannabinum Indian hemp ASTERACEAE - Sunflower family Achillea millefolium Yarrow Agoseris glauca Mountain dandelion Antennaria rosea Pussy toes Arnica mollis Cordilleran arnica Artemisia douglasiana Mugwort A. dracunculus Tarragon/Lemon sage A. ludoviciana Silver wormwood A. tridentata v. tridentata Great basin sage Balsamorhiza sagittata Balsamroot Chrysothamnus nauseosus Rubber rabbitbrush C. viscidiflorus Yellow or Wavy-leaf rabbitbrush Crepis intermedia Hawksbeard Erigeron sp. Fleabane Hulsea heterochroma Red-rayed hulsea Layia glandulosa ssp. glandulosa Tidytips Madia elegans ssp. wheeleri Common madia Tetrademia canescens Soft-leaved horsebrush Tragopogon dubius Goat's beard (WEED) Wyethia mollis Mule ears 1 BETULACEAE - Birch Family Betula occidentalis Western water birch BORAGINACEAE - Borage Family Cryptantha circumscissa v. circumscissa Capped cryptantha C. pterocarya C. utahensis Fragrant -

Molecular Investigation of the Origin of Castilleja Crista-Galli by Sarah

Molecular investigation of the origin of Castilleja crista-galli by Sarah Youngberg Mathews A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences Montana State University © Copyright by Sarah Youngberg Mathews (1990) Abstract: An hypothesis of hybrid origin of Castilleja crista-galli (Scrophulariaceae) was studied. Hybridization and polyploidy are widespread in Castilleja and are often invoked as a cause of difficulty in defining species and as a speciation model. The putative allopolyploid origin of Castilleja crista-gralli from Castilleja miniata and Castilleja linariifolia was investigated using molecular, morphological and cytological techniques. Restriction site analysis of chloroplast DNA revealed high homogeneity among the chloroplast genomes of species of Castilleja and two Orthocarpus. No species of Castilleia represented by more than one population in the analysis was characterized by a distinctive choroplast genome. Genetic distances estimated from restriction site mutations between any two species or between genera are comparable to distances reported from other plant groups, but both intraspecific and intrapopulational distances are high relative to other groups. Restriction site analysis of nuclear ribosomal DNA revealed variable repeat types both within and among individuals. Qualitative species groupings based on restriction site mutations in the ribosomal DNA repeat units do not place Castilleja crista-galli with either putative parent in a consistent manner. A cladistic analysis of 11 taxa using 10 morphological characters places Castilleja crista-galli in an unresolved polytomy with both putative parents and Castilleja hispida. Cytological analyses indicate that Castilleja crista-gralli is not of simple allopolyploid origin. Both diploid and tetraploid chromosome counts are reported for this species, previously known only as an octoploid. -

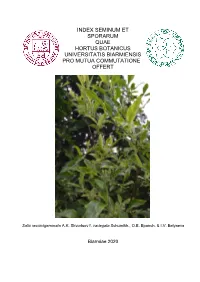

Index Seminum Et Sporarum Quae Hortus Botanicus Universitatis Biarmiensis Pro Mutua Commutatione Offert

INDEX SEMINUM ET SPORARUM QUAE HORTUS BOTANICUS UNIVERSITATIS BIARMIENSIS PRO MUTUA COMMUTATIONE OFFERT Salix recurvigemmata A.K. Skvortsov f. variegata Schumikh., O.E. Epanch. & I.V. Belyaeva Biarmiae 2020 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ СПИСОК СЕМЯН И СПОР, ПРЕДЛАГАЕМЫХ ДЛЯ ОБМЕНА БОТАНИЧЕСКИМ САДОМ ИМЕНИ А.Г. ГЕНКЕЛЯ ПЕРМСКОГО ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ИССЛЕДОВАТЕЛЬСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА Syringa vulgaris L. ‘Красавица Москвы’ Пермь 2020 Index Seminum 2020 2 Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education «Perm State National Research University», A.G. Genkel Botanical Garden ______________________________________________________________________________________ Дорогие коллеги! Ботанический сад Пермского государственного национального исследовательского университета был создан в 1922 г. по инициативе и под руководством проф. А.Г. Генкеля. Здесь работали известные ученые – ботаники Д.А. Сабинин, В.И. Баранов, Е.А. Павский, внесшие своими исследованиями большой вклад в развитие биологических наук на Урале. В настоящее время Ботанический сад имени А.Г. Генкеля входит в состав регионального Совета ботанических садов Урала и Поволжья, Совет ботанических садов России, имеет статус научного учреждения и особо охраняемой природной территории. Основными научными направлениями работы являются: интродукция и акклиматизация растений, -

Of Plant Diseases in South Carolina

Plant Common Name Index to INDEX OF PLANT DISEASES IN SOUTH CAROLINA James H. Blake, Ed.D., Meg Williamson, M.S., Kathy Ellingson, M.S. Common Name Family Genus/Species Page Abelia, Glossy CAPRIFOLIACEAE Abelia grandiflora 31 African Bush Daisy ASTERACEAE Euryops chrysanthemoides 19 African Daisy ASTERACEAE Arctotis sp. 16 African Lily AMARYLLIDACEAE Agapanthus sp. 5 African Marigold ASTERACEAE Tagetes erecta 21 African Violet GESNERIACEAE Saintpaulia sp. 56 Alfalfa FABACEAE Medicago sativa 49 Algerian Ivy ARALIACEAE Hedera canariensis 13 Almond ROSACEAE Prunus sp. 100 Aloe LILIACEAE Aloe sp. 64 Aloe Vera LILIACEAE Aloe barbadensis 64 Alternanthera AMARANTHACEAE Alternanthera sp. 5 Althaea MALVACEAE Althaea sp. 70 Alyssum BRASSICACEAE Lobularia sp. 29 Amaryllis AMARYLLIDACEAE Amaryllis sp. 6 American Beech FAGACEAE Fagus grandifolia 52 American Boxwood BUXACEAE Buxus sempervirens 29 American Holly AQUIFOLIACEAE Ilex opaca 10 American Mountain Ash OLEACEAE Sorbus americana 74 Anacyclus ASTERACEAE Anacyclus sp. 16 Anemone, Japanese RANUNCULACEAE Anemone hupehensis 93 Anise Hyssop LAMIACEAE Agastache foeniculum 60 Anise Tree ILLICIACEAE Illicium sp. 58 Annual Bluegrass POACEAE Poa annua 86 Annual Clary Sage LAMIACEAE Salvia viridis 63 Annual Vinca APOCYNACEAE Catharanthus roseus 7 Annual Vinca APOCYNACEAE Catharanthus sp. 7 Anthurium ARACEAE Anthurium sp. 11 Apple ROSACEAE Malus sp. 96 Apple, Common ROSACEAE Malus sylvestris pumila 96 Apricot ROSACEAE Prunus armeniaca 98 Aralia ARALIACEAE Aralia sp. 12 Aralia Ivy ARALIACEAE x Fatshedera sp. 12 Aralia, Ming ARALIACEAE Polyscias fruticosa 14 Arborvitae CUPRESSACEAE Thuja occidentalis 41 Arborvitae sp. CUPRESSACEAE Thuja sp. 41 Armandii Clematis RANUNCULACEAE Clematis armandii 93 Aromi Azalea EBENACEAE Rhododendron x aromi 44 Aromi Azalea EBENACEAE Rhododendron x aromi 44 Artemisia ASTERACEAE Artemisia schmidtiana 16 Artichoke ASTERACEAE Cynara scolymus 15 Arugula BRASSICACEAE Arugula sp. -

Okanogan County Plant List by Scientific Name

The NatureMapping Program Washington Plant List Revised: 9/15/2011 Okanogan County by Scientific Name (1) Non- native, (2) ID Scientific Name Common Name Plant Family Invasive √ 763 Acer glabrum Douglas maple Aceraceae 3 Acer macrophyllum Big-leaf maple Aceraceae 800 Alisma graminium Narrowleaf waterplantain Alismataceae 19 Alisma plantago-aquatica American waterplantain Alismataceae 1155 Amaranthus blitoides Prostrate pigweed Amaranthaceae 1087 Rhus glabra Sumac Anacardiaceae 650 Rhus radicans Poison ivy Anacardiaceae 1230 Berula erecta Cutleaf water-parsnip Apiaceae 774 Cicuta douglasii Water-hemlock Apiaceae 915 Cymopteris terebinthinus Turpentine spring-parsley Apiaceae 167 Heracleum lanatum Cow parsnip Apiaceae 1471 Ligusticum canbyi Canby's lovage Apiaceae 991 Ligusticum grayi Gray's lovage Apiaceae 709 Lomatium ambiguum Swale desert-parsley Apiaceae 1475 Lomatium brandegei Brandegee's lomatium Apiaceae 573 Lomatium dissectum Fern-leaf biscuit-root Apiaceae Coeur d'Alene desert- Lomatium farinosum Apiaceae 548 parsley 582 Lomatium geyeri Geyer's desert-parsley Apiaceae 586 Lomatium gormanii Gorman's desert-parsley Apiaceae 998 Lomatium grayi Gray's desert-parsley Apiaceae 999 Lomatium hambleniae Hamblen's desert-parsley Apiaceae 609 Lomatium macrocarpum Large-fruited lomatium Apiaceae 1476 Lomatium martindalei Few-flowered lomatium Apiaceae 1000 Lomatium nudicaule Pestle parsnip Apiaceae 1477 Lomatium piperi Piper's bisciut-root Apiaceae 634 Lomatium triternatum Nine-leaf lomatium Apiaceae 1528 Osmorhiza berteroi Berter's sweet-cicely -

A Checklist of the Alpine Vascular Flora of the Teton Range, Wyoming, with Notes on Biology and Habitat Preferences

Great Basin Naturalist Volume 41 Number 2 Article 11 6-30-1981 A checklist of the alpine vascular flora of the Teton Range, Wyoming, with notes on biology and habitat preferences John R. Spence Utah State University Richard J. Shaw Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn Recommended Citation Spence, John R. and Shaw, Richard J. (1981) "A checklist of the alpine vascular flora of the Teton Range, Wyoming, with notes on biology and habitat preferences," Great Basin Naturalist: Vol. 41 : No. 2 , Article 11. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/gbn/vol41/iss2/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Basin Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A CHECKLIST OF THE ALPINE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE TETON RANGE, WYOMING, WITH NOTES ON BIOLOGY AND HABITAT PREFERENCES Shaw^ John R. Spence''^ and Richard J. Abstract.— A checkHst of the vascular flora of the alpine zone (treeless vegetation above 9500 feet or 2900 m) of the Teton Range is presented. For each of the 216 species, si.x attributes are listed: flower color and shape, pollina- tion mode, life form, habitat preference, and whether each species is found in the Arctic. White and yellow flowered species are most common, and zoophilous species greatly predominate over anemophilous and apomictic species. Perennial/biennial herbs are the most common life form. -

Chapter 4 Phytogeography of Northeast Asia

Chapter 4 Phytogeography of Northeast Asia Hong QIAN 1, Pavel KRESTOV 2, Pei-Yun FU 3, Qing-Li WANG 3, Jong-Suk SONG 4 and Christine CHOURMOUZIS 5 1 Research and Collections Center, Illinois State Museum, 1011 East Ash Street, Springfield, IL 62703, USA, e-mail: [email protected]; 2 Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Russian Academy of Sciences, Vladivostok, 690022, Russia, e-mail: [email protected]; 3 Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, P.O. Box 417, Shenyang 110015, China; 4 Department of Biological Science, College of Natural Sciences, Andong National University, Andong 760-749, Korea, e-mail: [email protected]; 5 Department of Forest Sciences, University of British Columbia, 3041-2424 mail Mall, Vancouver, B.C., V6T 1Z4, Canada, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Northeast Asia as defined in this study includes the Russian Far East, Northeast China, the northern part of the Korean Peninsula, and Hokkaido Island (Japan). We determined the species richness of Northeast Asia at various spatial scales, analyzed the floristic relationships among geographic regions within Northeast Asia, and compared the flora of Northeast Asia with surrounding floras. The flora of Northeast Asia consists of 971 genera and 4953 species of native vascular plants. Based on their worldwide distributions, the 971 gen- era were grouped into fourteen phytogeographic elements. Over 900 species of vascular plants are endemic to Northeast Asia. Northeast Asia shares 39% of its species with eastern Siberia-Mongolia, 24% with Europe, 16.2% with western North America, and 12.4% with eastern North America. -

Molecular Phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), Including Artemisia and Its Allied and Segregate Genera Linda E

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences Papers in the Biological Sciences 9-26-2002 Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E. Watson Miami University, [email protected] Paul E. Bates University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Timonthy M. Evans Hope College, [email protected] Matthew M. Unwin Miami University, [email protected] James R. Estes University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub Watson, Linda E.; Bates, Paul E.; Evans, Timonthy M.; Unwin, Matthew M.; and Estes, James R., "Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera" (2002). Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences. 378. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/bioscifacpub/378 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications in the Biological Sciences by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research2 BMC2002, Evolutionary article Biology x Open Access Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera Linda E Watson*1, Paul L Bates2, Timothy M Evans3,