Changing Nature of the NSW Economy Background Paper No 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inaugural Speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith

Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament Briefing Paper No 4/2013 by Gareth Griffith ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to thank officers from both Houses for their comments on a draft of this paper, in particular Stephanie Hesford and Jonathan Elliott from the Legislative Assembly and Stephen Frappell and Samuel Griffith from the Legislative Council. Thanks, too, to Lenny Roth and Greig Tillotson for their comments and advice. Any errors are the author’s responsibility. ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 978 0 7313 1900 8 May 2013 © 2013 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior consent from the Manager, NSW Parliamentary Research Service, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Inaugural speeches in the NSW Parliament by Gareth Griffith NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Gareth Griffith (BSc (Econ) (Hons), LLB (Hons), PhD), Manager, Politics & Government/Law .......................................... (02) 9230 2356 Lenny Roth (BCom, LLB), Acting Senior Research Officer, Law ............................................ (02) 9230 3085 Lynsey Blayden (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Law ................................................................. (02) 9230 3085 Talina Drabsch (BA, LLB (Hons)), Research Officer, Social Issues/Law ........................................... (02) 9230 2484 Jack Finegan (BA (Hons), MSc), Research Officer, Environment/Planning..................................... (02) 9230 2906 Daniel Montoya (BEnvSc (Hons), PhD), Research Officer, Environment/Planning ..................................... (02) 9230 2003 John Wilkinson (MA, PhD), Research Officer, Economics ...................................................... (02) 9230 2006 Should Members or their staff require further information about this publication please contact the author. -

Annual Report 2018/19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018/19 BIG IDEAS BRIGHTER TOMORROW TARGETING: BY: PARTNERING WITH THE AUSTRALIAN CONTENTS ZERO DEATHS COMMUNITY TO CHAMPION WORLD- FROM BREAST CLASS BREAST CANCER RESEARCH TO CREATE A BETTER TOMORROW INTRODUCTION CANCER FOR ALL THOSE IMPACTED. Chair and CEO Report 2 Research Report 4 RESEARCH Driving innovative research 5 Identifying gaps in services and treatment 7 Immunotherapy to ‘BEAT’ breast cancer 8 Liquid biopsies under development for breast cancer 9 NBCF ORGANISATIONAL GOVERNANCE AND STRUCTURE New treatments for breast cancer metastases to the brain 10 Connecting Australia to the best research institutions in the world 11 Achievements against our research plan 12 Cancer prevention 13 BOARD OF AWARDS AND RECOGNITION DIRECTORS External recognition 14 Chair: Elaine Henry OAM FUNDRAISING Fundraising Report 16 17 CHIEF RESEARCH Long-lasting partnerships to be proud of EXECUTIVE ADVISORY FlyPink returns, bigger and better 18 OFFICER COMMITTEE Mother’s Day Classic 19 Professor Chair: Community fundraising movers and shakers 20 MARKETING Sarah Hosking Professor Ross RESEARCH Hannan Circle of 10 21 Rebecca Dr Chris Patton Pettigrew Thank you to all of our supporters 22 GOVERNANCE Income and Research Investment 24 Corporate Governance 26 FUNDRAISING OPERATIONS Concise Financial Statements 28 Moana Helen Wood Wild PEOPLE AND CULTURE Wendy Byrne National Breast Cancer Foundation: Annual Report 2018/19 (ABN 37 144 841 707) National Breast Cancer Foundation: Annual Report 2018/19 National Breast Cancer Foundation: Annual Report -

Trevor Hart Banking in a New World: the Beginnings of ANZ Bank

Trevor Hart Banking in a new world: the beginnings of ANZ Bank Proceedings of the ICOMON meetings, held in conjunction with the ICOM Conference, Melbourne (Australia, 10-16 October, 1998), ed. by Peter Lane and John Sharples. Melbourne, Numismatic Association of Australia, Inc, 2000. 117 p. (NAA Special publication, 2). (English). pp. 39-46 Downloaded from: www.icomon.org BANKING IN A NEW WORLD THE BEGINNINGS OF ANZ BANK By Trevor Hart ANZ Bank, Melbourne, Australia For its first twenty-nine years proposed to the Government in Australia had no bank. The British England, the formation of "The New settlement of Australia began in South Wales Loan Bank" based on 1788, but Australia's first bank, the the bank at the Cape of Good Hope. Bank of New South Wales, did not In 1812 the government refused open until 1817. his proposal. Macquarie accepted this refusal but was still convinced of Australia was founded as a the need for a bank in the colony.4 In self-supporting penal colony and 1816 he acted again, this time monetary arrangements were ad hoc. "convening a meeting of the A local currency of small private magistrates, principal merchants and promissory notes grew up in gentlemen of Sydney ... at which my conjunction with the circulation of favourite measure of a bank was Government Store receipts. This led brought forward."5 Macquarie issued to a dual monetary standard in a 'charter' for seven years to the which 'currency' came to mean directors of the new bank (which "money of purely local was later disallowed by the British acceptability" and 'sterling' meant Government) and on 8 April 1817 "any form of money .. -

Annual Report 2012 Report Annual

ANNUAL REPORT DAVID DAVID JONES 2012 ANNUAL REPORT 2012 For Corporate and Customer information please visit us at davidjones.com.au DAVID JONES LIMITED ABN 75 000 074 573 ACN 000 074 573 DJ1791_Annual Report.indd 1 12/09/12 3:18 PM CONTENTS Performance Analysis 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS USED IN THE ANNUAL REPORT Chairman’s and Chief Executive Officer AASB Australian Accounting Standards Board and Managing Director’s Report 2 American Express American Express Australia Limited Five Year Financial Statistics 7 ASX Australian Securities Exchange Executive Committee 8 Board The Board of Directors of David Jones Limited Corporate Governance Statement 9 CODB Cost of Doing Business Corporate Sustainability Report 26 Company David Jones Limited Directors’ Report 38 Corporations Act The Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) Remuneration Report 45 Consolidated Entity David Jones Limited and its controlled entities, Financial Statements 71 as listed in note 30 to the financial statements Directors’ Declaration 127 David Jones David Jones Limited Auditor’s Independence Declaration 128 DRP Dividend Reinvestment Plan Independent Audit Report 129 EBIT Earnings Before Interest and Tax Shareholder Information 131 EPS Earnings Per Share Corporate Directory 132 FY Financial Year IFRS International Financial Reporting Standards NPAT Net Profit After Tax OH&S Occupational Health and Safety Trust David Jones Incentive Plan Trust 2012 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING The Annual General Meeting will be held on Friday 23 November 2012 at 10.00 a.m. at On Seven at David Jones, Level 7, 86–108 Castlereagh Street, Sydney, New South Wales. The Notice of Meeting and Proxy Form are separate items accompanying this 2012 Annual Report. -

Big Business in Twentieth-Century Australia

CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC HISTORY THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY SOURCE PAPER SERIES BIG BUSINESS IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY AUSTRALIA DAVID MERRETT UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE SIMON VILLE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG SOURCE PAPER NO. 21 APRIL 2016 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY ACTON ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA T 61 2 6125 3590 F 61 2 6125 5124 E [email protected] https://www.rse.anu.edu.au/research/centres-projects/centre-for-economic-history/ Big Business in Twentieth-Century Australia David Merrett and Simon Ville Business history has for the most part been dominated by the study of large firms. Household names, often with preserved archives, have had their company stories written by academics, journalists, and former senior employees. Broader national studies have analysed the role that big business has played in a country’s economic development. While sometimes this work has alleged oppressive anti-competitive behaviour, much has been written from a more positive perspective. Business historians, influenced by the pioneering work of Alfred Chandler, have implicated the ‘visible hand’ of large scale enterprise in national economic development particularly through their competitive strategies and modernised governance structures, which have facilitated innovation, the integration of national markets, and the growth of professional bureaucracies. While our understanding of the role of big business has been enriched by an aggregation of case studies, some writers have sought to study its impact through economy-wide lenses. This has typically involved constructing sets of the largest 100 or 200 companies at periodic benchmark years through the twentieth century, and then analysing their characteristics – such as their size, industrial location, growth strategies, and market share - and how they changed over time. -

The History Journal Volume 14

annual service of rededication Order of St John St Hohn Historyenduring faith Awkward Hours, Awkward Jobs Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia Christ Church Anglican Cathedral Frank Dunstan MStJ Darwin Historical Society of Australia annual service of rededication Order of St John St Hohn Historyenduring faith THE JOURNAL OF THE ST JOHN AMBULANCE HISTORICALCapitular SOCIETY Procession OF AUSTRALIA of the Priory in Australia Christ ChurchVOLUME Anglican 14, 2014 Cathedral ‘Preserving and promoting the St John heritage’ Historical Society of Australia Darwin Frank Dunstan MStJ Awkward Hours, Awkward Jobs The front cover of St John History Volume 14 shows the members of the Order of St John who took part in the Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia at their annual service of rededication in Christ Church Capitular Procession of the Priory in Australia Anglican Cathedral in Darwin on Sunday 2 June 2013. enduring faith The members of the Order are pictured outside the porch of the cathedral, which is all that remains of the original structure built and consecrated in 1902. Constructed from the local red limestone, the original Christ Church Anglican Cathedral cathedral was damaged during a Japanese air raid in February 1942. After that the Australian military forces annual service of rededication used the building until the end of the war. Cyclone Tracy destroyed everything but the porch of the repaired cathedral in December 1974. Order of St John The new cathedral, built around and behind the porch, was consecrated in the presence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Most Reverend Donald Coggan, on 13 March 1977. -

NSW and Gambling Revenue Briefing Paper No. 16/96

NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE NSW and Gambling Revenue by John Wilkinson Briefing Paper No. 16/96 NSW PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY RESEARCH SERVICE Dr David Clune (230 2484), Manager Ms Honor Figgis (230 2768) Research Officer, Law Dr Gareth Griffith (230 2356) Senior Research Officer, Politics and Government Ms Fiona Manning (230 3085) Research Officer, Law/Social Issues Mr Stewart Smith (230 2798) Research Officer, Environment Ms Marie Swain (230 2003) Research Officer, Law Mr John Wilkinson (230 2006) Research Officer, Economics ISSN 1325-5142 ISBN 0 7310 5957 3 © 1996 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means includin g information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from th e Librarian, New South Wales Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the New South Wales Parliament in the course of their official duties. Should Members or their staff require further information about this publicatio n please contact the author. October 1997 Briefing Paper is published by the NSW Parliamentary Library CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Introduction ................................................. .3 2. Previous Occurrences of Government Recourse to Revenue from Gambling ..................................... .4 3. The Expansion of Racing, Poker Machine Playing and Lotteries in NSW ..6 4. The Circumstances of Government Inclination towards Gambling as a Source of Revenue ................................ 14 5. Basic Economic and Financial Breakdown of Gambling, and Government Revenue from Gambling, in New South Wales ........16 6. The Expansion of NSW Government Revenue Raising from Gambling: By Category .............................21 7. -

Assessment Documentation

REGISTER OF HERITAGE PLACES – ASSESSMENT DOCUMENTATION 11. ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HERITAGE SIGNIFICANCE The criteria adopted by the Heritage Council in November 1996 have been used to determine the cultural heritage significance of the place. PRINCIPAL AUSTRALIAN HISTORIC THEME(S) • 3.18 .2 Banking and lending • 5.4 Working in offices • 8.14 Living in the country and rural settlements HERITAGE COUNCIL OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA THEME(S) • 301 Grazing & pastoralism & dairying • 302 Rural industry & market gardening • 306 Domestic activities • 308 Commercial & service industries 11.1 AESTHETIC VALUE* The fine design detail in the Federation Free Classical style and vertical scale of ANZ Bank, Northam creates a building of significant presence in the streetscape. (Criterion 1.1 and 1.2) The classical order and vertical scale of ANZ Bank, Northam creates an imposing presence in the streetscape of the Northam business district. (Criterion 1.3) 11.2 HISTORIC VALUE ANZ Bank, Northam is associated with the development of banking facilities in the agricultural regions of the State in the early part of the twentieth century. The scale of the building and the materials used reflect the confidence the Union Bank had for the Northam area at that time. (Criterion 2.1) ANZ Bank, Northam is the oldest operating bank building in Northam, and has housed banking functions from 1906 to the present (2006). (Criterion 2.2) ANZ Bank, Northam is closely associated with the financial life of Northam and surrounding farming districts, having been purpose built for the bank’s predecessor, the Union Bank, in 1906. (Criterion 2.3) * For consistency, all references to architectural style are taken from Apperly, R., Irving, R., Reynolds, P. -

Malcolm Pearse, 'Australia's Early Managers'

AUSTRALIA’S EARLY MANAGERS Malcolm Pearse1 Macquarie University Abstract The origins of managers and management have been studied comprehensively in Great Britain, Europe and the United States of America, but not in Australia. Most scholars have looked at Australia’s history in the twentieth century to inform the literature on the modern enterprise, big business and management, but the role of the manager or agent was established in many businesses by the 1830s. There were salaried managers in Australia as early as 1799, appointed to oversee farms. The appointment of managers in Australia from as early as 1799 continued the practice of British institutions in some industries. But in other contexts, management practice departed from British practice, demonstrating largely adaptive, rather than repetitive features. As the wool industry dominated the economy, the range of industries grew and managers or agents were appointed to businesses such as public companies, which were formed from at least 1824. During the 1830s, there were managers of theatres, hotels, merchant houses, and in whaling, cattle, sheep, shipping and banking activities. As banking expanded during the 1830s and 1840s, so did the number of managers. Bank managers were appointed both with the entry of new banks and with branch expansion. As banks expanded their branch network, the number of managers increased. The establishment of branches continued another British institution in the colonial context and further reinforced the manager’s role. The rise of the salaried manager in Australia was harnessed to the rise of the public company and began as early as the 1840s but was more evident during the second half of the nineteenth century, when public companies grew bigger and prominent in strategically important industries such as grazing, sugar, water, engineering, electricity, banking, insurance and shipping, river and stage coach transport. -

WHL 201404090004A Proposed Acquisition by Woolworths Holdings

WHL 201404090004A Proposed Acquisition by Woolworths Holdings Limited of David Jones Limited and Cautionary announcement WOOLWORTHS HOLDINGS LIMITED (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) Registration number 1929/001986/06 Share code: WHL ISIN: ZAE000063863 (“WHL” or “the Company” or “the Group”) NOT FOR RELEASE, PUBLICATION OR DISTRIBUTION, IN WHOLE OR IN PART, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, IN, INTO OR FROM THE UNITED STATES OR ANY JURISDICTION WHERE TO DO SO WOULD CONSTITUTE A VIOLATION OF APPLICABLE LAW OR REGULATION ANNOUNCEMENT REGARDING THE PROPOSED ACQUISITION BY WHL OF DAVID JONES LIMITED (“DAVID JONES”) AND CAUTIONARY ANNOUNCEMENT 1. INTRODUCTION The board of directors of WHL (the “Board”) is pleased to announce that it has reached agreement with David Jones to acquire, through a wholly-owned Australian subsidiary, the entire issued share capital of David Jones, a major Australian department store retailer, at a cash price of A$4.00 per share (the “Proposed Acquisition”), representing a total cash consideration of A$2.1 billion (approximately R21.4 billion) (the “Consideration”).* The Proposed Acquisition will be implemented by way of a Scheme of Arrangement (“Scheme”) between David Jones and its shareholders under the Australian Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (“Corporations Act”). WHL entered into a Scheme Implementation Deed (“SID”) with David Jones on Wednesday, 9 April 2014, which governs the implementation of the Scheme. The David Jones board of directors (“David Jones Board”) unanimously recommend that the David Jones shareholders (“David Jones Shareholders”) vote in favour of the Scheme, in the absence of a “Superior Proposal” (as defined in the SID) and subject to an Independent Expert concluding that the Proposed Acquisition is fair and reasonable and in the best interests of David Jones Shareholders. -

670 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL GAZETTE 26 November, 2004

670 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL GAZETTE 26 November, 2004 ########################################################################################################################### QUEENSLAND INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS COMMISSION Trading (Allowable Hours) Act 1990 – s. 21 – trading hours order on non-exempt shops National Retail Association Limited, Union of Employers AND Queensland Retail Traders and Shopkeepers Association (Industrial Organization of Employers) and Others (No. B1212 of 2004) National Retail Association Limited, Union of Employers AND Queensland Retail Traders and Shopkeepers Association (Industrial Organization of Employers) and Others (No. B1213 of 2004) TRADING HOURS ORDER – NON-EXEMPT SHOPS TRADING BY RETAIL – STATE DEPUTY PRESIDENT BLOOMFIELD COMMISSIONER EDWARDS COMMISSIONER BROWN 17 November 2004 Applications to amend the Trading Hours Order – Non-Exempt Shops Trading By Retail – State – Continuous trade proposed on 23/24 December at Pacific Fair Shopping Complex and Robina Town Centre Shopping Complex – Witness evidence – Nothing special, unique or telling about either application – Both applications dismissed. DECISION This decision relates to 2 applications lodged by the National Retail Association Limited, Union of Employers (NRA) to amend the Trading Hours Order – Non-Exempt Shops Trading by Retail – State (the Order) pursuant to s. 21 of the Trading (Allowable Hours) Act 1990 (the Act). 26 November, 2004 QUEENSLAND GOVERNMENT INDUSTRIAL GAZETTE 671 The first application (Matter No. B1212 of 2004) seeks to amend the Order to allow the Pacific Fair Shopping Complex (Pacific Fair) to trade from 12.00 midnight on 23 December until 8.00 a.m. on 24 December of each year provided that where 23 December falls on a Saturday or Sunday additional hours will operate from midnight on the Thursday prior to Christmas Day until 8.00 a.m. -

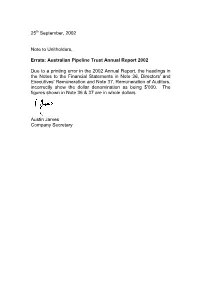

Australian Pipeline Trust Annual Report 2002 Due to a Printing Error in the 2002

25th September, 2002 Note to Unitholders, Errata: Australian Pipeline Trust Annual Report 2002 Due to a printing error in the 2002 Annual Report, the headings in the Notes to the Financial Statements in Note 36, Directors' and Executives' Remuneration and Note 37, Remuneration of Auditors, incorrectly show the dollar denomination as being $'000. The figures shown in Note 36 & 37 are in whole dollars. Austin James Company Secretary Annual Report 2002 Australian Pipeline Trust ARSN 091 678 778 QUICK FACTS • Australian Pipeline Trust is listed on the Australian Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol ‘APA’ • APA is an industry leader in gas transmission infrastructure. APA has an interest in more than 7,000km of pipelines and a 25% share of Australia’s natural gas transmission market • APA had 244 million units on issue at 30 June 2002, held by 28,796 unitholders. CONTENTS Corporate Highlights 1 Annual Financial Report 2002 Key Issues 2 Corporate Governance 10 Chairman’s Report 4 Directors’ Report 15 Managing Director’s Report 6 Statement of Financial Performance 24 The Management Team 8 Statement of Financial Position 25 Glossary of Terms, Statement of Cash Flows 26 Directory Notes to the Financial Statements 27 and Financial Calendar Inside back cover Directors’ Declaration 57 Independent Audit Report 58 Additional Stock Exchange Information 59 Unitholder Information 60 ‘Our goal is clear – Australian Pipeline Trust will continue to be recognised as the leading transporter of natural gas in Australia while at the same time exploring further ventures that have the potential to provide a sound return to our unitholders.’ IFC2 Jim McDonald, Managing Director Australian Pipeline Limited IFC2 Australian Pipeline Trust • Annual Report 2002 CORPORATE HIGHLIGHTS Photo: Wagga Wagga to Culcairn Pipeline – Murrumbidgee River, NSW YEAR AT A GLANCE FINANCIAL SUMMARY G Period ended Operating Profit after Tax and Minorities of 30 June 2001 $37.1million, an increase of 20.8% over previous Year ended Year ended (17 March 2000 corresponding period (“pcp”).