Community Health: the State of Play in NSW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Vermont, College of Medicine Bulletin University of Vermont

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM University of Vermont College of Medicine University Libraries Catalogs 1947 University of Vermont, College of Medicine Bulletin University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/dmlcatalog Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation University of Vermont, "University of Vermont, College of Medicine Bulletin" (1947). University of Vermont College of Medicine Catalogs. 93. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/dmlcatalog/93 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Libraries at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Vermont College of Medicine Catalogs by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE MEDICAL COLLEGE 4 BULLETIN OF THE h UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT AND STATE AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE BURLINGTON VERMONT I VOLUME XLIV - OCTOBER 1947 - NUMBER 4 THE COLLEGE OF MEDICINE NUMBER Published by the University of Verm01tt and State Agricultural College, Burlington, Vermor>t, fi ve times a year, Jamtary, March, April, October ami November atld entered as second-class matter, ]mze 24, 19 32, at the Post Office at Burlir>gton, Vert,ont, under Act of Cot<gress of August 24, 1912 CALENDAR 1947 July 3, Thursday. Enrollment of Senior Class. July 7, Monday. Hospital work for Seniors beg~s. September 15, Monday. Examinations for Advancement in Course. September 19, Friday. Convocation. September 20, Saturday. Enrollment of three lower classes. September 22, Monday. Regular exercises begin. November 26, Wednesday, 11:50 a.m. to December I, Monday, 8:30a.m. Thanksgiving Recess. -

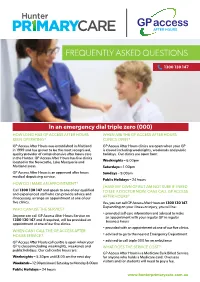

Download GP Access After Hours FAQ

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS 1300 130 147 In an emergency dial triple zero (000) HOW LONG HAS GP ACCESS AFTER HOURS WHEN ARE THE GP ACCESS AFTER HOURS BEEN OPERATING? CLINICS OPEN? GP Access After Hours was established in Maitland GP Access After Hours clinics are open when your GP in 1999 and has grown to be the most recognised, is closed including weeknights, weekends and public quality provider of comprehensive after hours care holidays. Our clinics are open from: in the Hunter. GP Access After Hours has five clinics located in the Newcastle, Lake Macquarie and Weeknights – 6.00pm Maitland areas. Saturdays – 1.00pm GP Access After Hours is an approved after hours Sundays – 9.00am medical deputising service. Public Holidays – 24 hours HOW DO I MAKE AN APPOINTMENT? I HAVE MY OWN GP BUT AM NOT SURE IF I NEED Call 1300 130 147 and speak to one of our qualified TO SEE A DOCTOR NOW, CAN I CALL GP ACCESS and experienced staff who can provide advice and if necessary, arrange an appointment at one of our AFTER HOURS? five clinics. Yes, you can call GP Access After Hours on 1300 130 147. Depending on your illness or injury, you will be: WHO CAN USE THE SERVICE? • provided self-care information and advised to make Anyone can call GP Access After Hours Service on an appointment with your regular GP in regular 1300 130 147 and if required, will be provided an business hours appointment at one of our five clinics. • provided with an appointment at one of our five clinics WHEN CAN I CALL THE GP ACCESS AFTER HOURS SERVICE? • advised to go to the nearest Emergency Department GP Access After Hours call centre is open when your • advised to call triple 000 for an ambulance GP is closed including weeknights, weekends and WHAT DOES THE SERVICE COST? public holidays. -

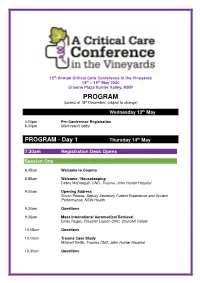

PROGRAM (Correct at 18 Th December, Subject to Change)

15th Annual Critical Care Conference in the Vineyards 14 th – 15 th May 2020 Crowne Plaza Hunter Valley, NSW PROGRAM (correct at 18 th December, subject to change) th Wednesday 13 May 4.00pm - Pre-Conference Registration 6.00pm Main resort lobby PROGRAM - Day 1 Thursday 14 th May 7.30am Registration Desk Opens Session One 8.45am Welcome to Country 8.55am Welcome / Housekeeping Debra McDougall, CNC, Trauma, John Hunter Hospital 9.00am Opening Address Susan Pearce, Deputy Secretary Patient Experience and System Performance, NSW Health 9.30am Questions 9.35am Mass International Aeromedical Retrieval Emily Ragus, Disaster Liaison CNC, Churchill Fellow 10.05am Questions 10.10am Trauma Case Study Mitchell Smith, Trauma CNC, John Hunter Hospital 10.30am Questions 10.35am Morning Tea & Trade Display Session Two – Free papers 11.05am Providing better value care to low back pain patients in the Emergency Department Simon Davidson, PhD Candidate, University of Newcastle; Project Officer, HNELHD Population Health 11.25am Measured vs predictive energy expenditure in ventilated patients receiving enteral feeding in critical care: Preliminary results of an observational prospective study Amelia Scott, Dietitian, Concord Repatriation General Hospital 11.35am Usability testing via simulation for the Last Days of Life Toolkit (LDOL) Paediatric and Neonatal Narrell O’Dea, Senior Simulation Coordinator, John Hunter Hospital Simulation Centre 11.45am A “Polio Like” condition – two paediatric case studies Jenny Hall, CNC,ICU, John Hunter Hospital 12.05pm The -

Rehabilitation Stroke Services 2018 Supplement Strokefoundation.Org.Au

National Stroke Audit Rehabilitation Stroke Services 2018 Supplement strokefoundation.org.au 1 Introduction The contents of the following supplement should be read in relation to the National Stroke Foundation’s National Stroke Audit – Rehabilitation Services Report 2018. This report can be accessed from the Stroke Foundation’s new website, InformMe: https://informme.org.au/stroke-data National Stroke Audit National Stroke Audit Rehabilitation Services Rehabilitation Services Report 2018 Report 2018 strokefoundation.org.auNational Stroke strokefoundation.org.auAudit Rehabilitation Services Report 2018 strokefoundation.org.au 2 Appendix 1: Participating Hospitals We would like to thank everyone involved at all participating hospitals for their support and hard work on the National Stroke Audit – Rehabilitation Services 2018. New South Wales Hornsby & Ku-ring-gai Hospital Cesar Tuy, Chanelle Oen and team Armidale Hospital Amanda Styles and Jaclyn Birnie Hunter Valley Private Hospital Amanda Freund, Jessica Baker and team Ballina District Hospital Gloria Vann, Kim Hoffman and team John Hunter Hospital – Rankin Park Helen Baines and team Balmain Hospital Indu Nair and team Kurri Kurri Hospital Sue Skaife, Jennifer Walters, Karen Reid and team Bankstown Lidcombe Hospital Christine Fuller, Kevin Guo and team Lady Davidson Private Hospital Suellen Fulton and team Bathurst Hospital Amelia Burton and team Lourdes Hospital Kaylene Green and team Belmont Hospital Prerna Keshwan, Colette Sanctuary and team Maclean District Hospital Louise Massie and -

Calvary Mater Newcastle Review of Operations 2018-2019

Review of Operations 2018-19 Continuing the Mission of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary Contents The Spirit of Calvary 2 Management and Community Advisory Council 4 Report from the General Manager 6 Report from the Community Advisory Council 8 Department Reports 11 Activity and Statistical Information 57 Year in Review 58 A Snapshot of our Year 61 Research and Teaching Reports 62 Financial Report 2018-19 80 Acknowledgement of Land and Traditional Owners Calvary Mater Newcastle acknowledges the Traditional Custodians and Owners of the lands of the Awabakal Nation on which our service operates. We acknowledge that these Custodians have walked upon and cared for these lands for thousands of years. We acknowledge the continued deep spiritual attachment and relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to this country and commit ourselves to the ongoing journey of Reconciliation. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are respectfully advised that this publication may contain the words, names, images and/or descriptions of people who have passed away. 2018-19 Calvary Mater Newcastle Review of Operations | 1 The Spirit of Calvary Calvary Mater Newcastle is a service of the Calvary group that operates public and private hospitals, retirement communities, and community care services in four states and two territories in Australia. Our Mission identifies why we exist We strive to bring the healing ministry of Jesus to those who are sick, dying and in need through ‘being for others’: • In the Spirit of Mary standing by her Son on Calvary. • Through the provision of quality, responsive and compassionate health, community and aged care services based on Gospel values, and • In celebration of the rich heritage and story of the Sisters of the Little Company of Mary. -

John Hunter Hospital Birthing Services Hunter New England Local Health District

Welcome to the John Hunter Hospital Birthing Services Hunter New England Local Health District Information for women and their families November 2020 Acknowledgement of Country “We would like to acknowledge the Traditional Custodians and community members of the land John Hunter Hospital is situated on, The Awabakal People and pay our respects to Elders, past, present and future”. Artwork by Saretta Fielding Front page artwork “Mother and Child” designed and sculpted by Matthew Harding, 1991 from a single log of Tasmanian Myrtle. – 2 – Contents A Message From Our Service Manager ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 4 About This Booklet ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 About Us ............................................................................................................................................................. 5 When You Should Contact The Hospital ............................................................................................................ 6 Baby Friendly Accredited Hospital ...................................................................................................................... 7 Now That You Are Pregnant ............................................................................................................................... 8 Antenatal Clinic - General Information ............................................................................................................... -

Lhr-John-Hunter.Pdf

2018 Newcastle Local Health Report • Associate Professor Aaron Sverdlov - Ministerial Award for Rising Stars in Cardiovascular Research. Their success is the culmination of hard work and commitment Acknowledgement of Country to improving outcomes for the patients within our facility, and the broader community. The John Hunter Hospital acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land and waters surrounding Newcastle, the As a facility we have achieved Accreditation through the Awabakal people. We pay respect to knowledge holders and National Standard Accreditation Survey by the Australian community members of the land and acknowledge and pay Council on Healthcare Standards, and re-accreditation under respect to Elders past, present and future. the Baby Friendly Health Initiative (BFHI). Both of these achievements demonstrate our commitment to the highest standards of patient care and outcomes. Year at a Glance In pursuing our vision of Excellence, the focus for this past year has been on improving the patient experience. With this at the Our vision at John Hunter Hospital is to provide each patient forefront of decision making, we have: with world class care, exceptional service and the compassion • Launched the John Hunter Hospital public website to that we would want for ourselves and our loved ones. improve awareness and understanding of our facility This year’s Local Health Report will showcase a selection of and the services provided for patients and visitors the real success stories achieved at John Hunter Hospital - and health professionals. by clinicians, support staff, committees, volunteers and our • Upgraded our Cardiac Catheter Laboratories to community of consumers. enhance the ability to diagnose and treat coronary Throughout the year we have celebrated the accomplishments artery disease and heart disease at John Hunter of teams and individual clinicians: Hospital. -

06 Annual Report Cover.Indd

Hunter New England Area Health Service Annual Report 2005/2006 Hunter New England Area Health Setvice Hunter New England Health Lookout Road, New Lambton Heights, NSW 2305 Locked Bag 1, New Lambton NSW 2305 Telephone: (02) 4985 5522 Facsimile: (02) 4921 4969 All Hunter New England hospitals are open 24 hours. Letter to the Minister November 2006 Hon John Hatzistergos MP Minister for Health Parliament of NSW Macquarie Street, Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Mr Hatzistergos, I have pleasure in submitting the Hunter New England Area Health Service 2005/06 Annual Report. The Report complies with the requirements for annual reporting under the Accounts and Audit Determination for public health organisations and the 2005/06 Directions for Health Service Reporting. Contents Terry Clout CHIEF EXECUTIVE CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S MESSAGE 4 ORGANISATION 6 PERFORMANCE 16 OUR PEOPLE 68 OUR COMMUNITY 76 FINANCIAL REPORT 88 2005-2006 Highlights • Opening of the $100-million Royal • Establishment of a methamphetamine Newcastle Centre – the new home of treatment clinic as part of a State pilot specialist and outpatient services from to offer a range of targeted information Royal Newcastle Hospital and some and treatment services to people who medical, diagnostic and outpatient use the psycho-stimulant drug. services previously provided at John Hunter Hospital. • $100,000 additional funding over two years for the Memory Assessment • Highest coverage of immunisation for Program in Armidale to continue children 12-15 months of age in NSW its work in the early detection and with a rate of 92.9 per cent over the coordinated care of dementia past 12 months. -

Your Care During Pregnancy Patient Information

Your Care During Pregnancy This page includes specific advice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Now that you have decided to have your baby in the Newcastle area, you will generally be able to choose from several different types of care. Where you have your pregnancy care and where you have your baby will depend on your general health, your preferences, where you live, and your previous birth experiences. PREGNANCY AND BIRTHCARE OPTIONS PROVIDER LOW RISK MODERATE RISK HIGH RISK General Practitioner - shared care Belmont Midwifery Group - - Practice Private Obstetrician John Hunter Hospital Birth Centre Team - - Midwife care at Raymond - - Terrace BirthCentre care at - - Wallsend Outreach Midwife care at Belmont - - Outreach Midwife care at Toronto - - Outreach Midwife care at Tomaree - - Outreach Birra-Li Aboriginal - - Maternal and Child Health Service John Hunter antenatal - - clinic Obstetrician M3 Team (on specialist referral only) - - Private Obstetrician Your Care During Pregnancy - Patient Information Issued: 3 December 2015 HealthPathways:37900 Belmont Midwifery Group Practice This group offer one-to-one midwifery care throughout pregnancy, birth and postnatal experience. This service is based at Belmont Hospital, however care is also provided within your home and the community. The service is professionally and functionally linked with John Hunter Maternity and Gynaecology Services. It is only available to women who assessed as having a low risk pregnancy. John Hunter Hospital (JHH) – Antenatal Clinic Provides a range of antenatal services including midwifery-led care, shared care, and high risk specialist obstetrician care. Other services include social work, family care, physiotherapy, interpreter service, diet and nutrition advice, and diabetes education services. -

GNS Diabetes Service Diabetes Staff Orientation Guide January 2020

GREATER NEWCASTLE SECTOR DIABETES SERVICE GNS Diabetes Service Diabetes Staff Orientation Guide January 2020 Welcome to the Team Welcome to the Greater Newcastle Sector Diabetes Service. The service is part of Community and Aged Care Services (CACS) in the Greater Newcastle Sector (GNS) – one of the seven Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD) sectors. The service also supports adult diabetes medical clinics at John Hunter, Belmont and Maitland Hospitals. New employees to the Diabetes Service will also be provided with a copy of the Hunter New England Local Health District Orientation Guide for New Staff, as it contains generic information about working in our health service and the CACS-GNS Orientation Guide for New Staff, containing information about the Greater Newcastle Sector. It is recommended that the HNELHD Guide is read first, with the CACS-GNS Guide and this service orientation guide providing local and additional information to support you in your role. Common\Administration GNC Diabetes\Staff Orientation\2020 updated Staff Orientation documents\GNS Diabetes Service Orientation Guide Jan 2020 GREATER NEWCASTLE SECTOR DIABETES SERVICE About this Orientation Guide . Information can be used for the orientation of new staff to Greater Newcastle Sector Diabetes Service and for existing staff to update on procedures. New and existing staff can use the checklists that accompany this guide to monitor their training progress and competency, and participate in ongoing review. New staff will be allocated an orientation buddy to help guide them through the orientation process. Contents of this guide . Information about the adult diabetes services offered. Minimum Standards of Care in GNS Diabetes Service. -

COVID-19 Maternity Model of Care

Main Heading Main Heading SubSub Heading Heading COVID -19 Impact on Antenatal Care for Women and Maternity Care Providers John Hunter Hospital Maternity & Gynaecology COVID 19 Executive Carol Azzopardi Dr Andy Woods Dr Felicity Park Nicole Bennett Acknowledgment for the development of JHHCOVID-19 Maternity Model of Care. Dr Ailsa Foster, Dr Rina Fiyfe, Dr Felicity Park, Alison Beverley (CMC), Irene Chapman (ANC Team Leader), Sigrid Johnson (FCM), Wendy Tsang Chow Chang (MM3 K2), Kristal Thornton & Karlie Beith (Administration Team leaders) Dr John Bailey (Endocrine pathway), Dr Craig Pennell (Pre Term Birth Pathway). JHH Maternity Working Party 7 April 2020. Introduction: COVID-19 Pandemic Maternity Model of Antenatal Care. Situation To support and protect staff, protect women and babies and to maintain a safe essential maternity care for all women, an urgent redesign of antenatal care was essential for Maternity & Gynaecology. Background The rapidly changing progression of COVID-19 required the redesign of antenatal care for women having their pregnancy care at John Hunter Hospital. With limited time, the M&G COVID-19 Executive gave a brief to a small project team to redesign antenatal care to align with four key objectives:- 1. Reduce number of routine antenatal occasions of care 2. Ensure all essential visits coordinated to minimize number of visits and time in healthcare settings 3. Optimize use of alternative care delivery options: - Off-site clinics for low risk women - Telehealth 4. Minimize “traffic” in healthcare settings - Attend AN visit alone - Exceptions carefully individualized e.g. breaking bad news, very complex psychosocial situations A working party was nominated by the M&G COVID19 Executive and with guidance from RCOG, NSW Health and American Society of Maternal Fetal Medicine (MFM) recommendations the model was designed. -

PORTRAIT of a PHYSICIAN Oil by Nicholas Neufchatel (Flemish 1525 - 1590) the Text Translates As "Died September 20, 1562 at the Age of 75"

PORTRAIT OF A PHYSICIAN Oil by Nicholas Neufchatel (Flemish 1525 - 1590) The text translates as "Died September 20, 1562 at the age of 75". Donated to the Society by Homer Gage M.D. A Community Of Physicians The History of the Worcester District Medical Society 1954 - 1994 JOHN J. MASSARELLI, M.D. WORCESTER, MASSACHUSETTS WORCESTER DISTRICT MEDICAL SOCIETY Copyright 1995 by the Worcester District Medical Society All rights reserved. All or part of this book may be reproduced only with permission of the Worcester District Medical Society. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 9641948-1-3 PBS Designs Printed by Deerfield Press Worcester, MA CONTENTS v List of Illustrations Dedication vii Introduction ix THE FIFTIES THOSE WERE THE DAYS, MY FRIEND 1. State of the Worcester District Medical Society and Medicine in the Area in the Mid-1950s 1 2. Aftermath of the Tornado 17 3. Socialized Medicine: One 23 4. Other Business 25 THE SIXTIES TIME WAS 5. The Fairlawn Affair 33 6. The University of Massachusetts Medical School 39 7. The Worcester Medical Library 47 8. Socialized Medicine: Two 51 9. Old and New Business in the Sixties 57 10. The Worcester District Medical Society and Public Health 63 THE SEVENTIES THE WAY WE WERE 11. The Scholarship Committee 69 12. The School and the Society in the 1970s 73 13. The Structure of the Society 79 14. Singing the Blues 85 15. The Worcester Medical News in the 1970s 89 16. PSROs, EMS, NHI, HMOs, etc. 93 17. The Malpractice Problem 101 18. Other Issues 103 THE EIGHTIES IT SEEMS LIKE ONLY YESTERDAY 19.