Tranexamic Acid for Treatment and Prophylaxis of Bleeding and Hyperfibrinolysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

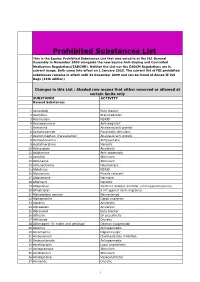

Prohibited Substances List

Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). Neither the List nor the EADCM Regulations are in current usage. Both come into effect on 1 January 2010. The current list of FEI prohibited substances remains in effect until 31 December 2009 and can be found at Annex II Vet Regs (11th edition) Changes in this List : Shaded row means that either removed or allowed at certain limits only SUBSTANCE ACTIVITY Banned Substances 1 Acebutolol Beta blocker 2 Acefylline Bronchodilator 3 Acemetacin NSAID 4 Acenocoumarol Anticoagulant 5 Acetanilid Analgesic/anti-pyretic 6 Acetohexamide Pancreatic stimulant 7 Acetominophen (Paracetamol) Analgesic/anti-pyretic 8 Acetophenazine Antipsychotic 9 Acetylmorphine Narcotic 10 Adinazolam Anxiolytic 11 Adiphenine Anti-spasmodic 12 Adrafinil Stimulant 13 Adrenaline Stimulant 14 Adrenochrome Haemostatic 15 Alclofenac NSAID 16 Alcuronium Muscle relaxant 17 Aldosterone Hormone 18 Alfentanil Narcotic 19 Allopurinol Xanthine oxidase inhibitor (anti-hyperuricaemia) 20 Almotriptan 5 HT agonist (anti-migraine) 21 Alphadolone acetate Neurosteriod 22 Alphaprodine Opiod analgesic 23 Alpidem Anxiolytic 24 Alprazolam Anxiolytic 25 Alprenolol Beta blocker 26 Althesin IV anaesthetic 27 Althiazide Diuretic 28 Altrenogest (in males and gelidngs) Oestrus suppression 29 Alverine Antispasmodic 30 Amantadine Dopaminergic 31 Ambenonium Cholinesterase inhibition 32 Ambucetamide Antispasmodic 33 Amethocaine Local anaesthetic 34 Amfepramone Stimulant 35 Amfetaminil Stimulant 36 Amidephrine Vasoconstrictor 37 Amiloride Diuretic 1 Prohibited Substances List This is the Equine Prohibited Substances List that was voted in at the FEI General Assembly in November 2009 alongside the new Equine Anti-Doping and Controlled Medication Regulations(EADCMR). -

Alphabetical Listing of ATC Drugs & Codes

Alphabetical Listing of ATC drugs & codes. Introduction This file is an alphabetical listing of ATC codes as supplied to us in November 1999. It is supplied free as a service to those who care about good medicine use by mSupply support. To get an overview of the ATC system, use the “ATC categories.pdf” document also alvailable from www.msupply.org.nz Thanks to the WHO collaborating centre for Drug Statistics & Methodology, Norway, for supplying the raw data. I have intentionally supplied these files as PDFs so that they are not quite so easily manipulated and redistributed. I am told there is no copyright on the files, but it still seems polite to ask before using other people’s work, so please contact <[email protected]> for permission before asking us for text files. mSupply support also distributes mSupply software for inventory control, which has an inbuilt system for reporting on medicine usage using the ATC system You can download a full working version from www.msupply.org.nz Craig Drown, mSupply Support <[email protected]> April 2000 A (2-benzhydryloxyethyl)diethyl-methylammonium iodide A03AB16 0.3 g O 2-(4-chlorphenoxy)-ethanol D01AE06 4-dimethylaminophenol V03AB27 Abciximab B01AC13 25 mg P Absorbable gelatin sponge B02BC01 Acadesine C01EB13 Acamprosate V03AA03 2 g O Acarbose A10BF01 0.3 g O Acebutolol C07AB04 0.4 g O,P Acebutolol and thiazides C07BB04 Aceclidine S01EB08 Aceclidine, combinations S01EB58 Aceclofenac M01AB16 0.2 g O Acefylline piperazine R03DA09 Acemetacin M01AB11 Acenocoumarol B01AA07 5 mg O Acepromazine N05AA04 -

Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021

EPHMRA ANATOMICAL CLASSIFICATION GUIDELINES 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 "The Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products has been developed and maintained by the European Pharmaceutical Marketing Research Association (EphMRA) and is therefore the intellectual property of this Association. EphMRA's Classification Committee prepares the guidelines for this classification system and takes care for new entries, changes and improvements in consultation with the product's manufacturer. The contents of the Anatomical Classification of Pharmaceutical Products remain the copyright to EphMRA. Permission for use need not be sought and no fee is required. We would appreciate, however, the acknowledgement of EphMRA Copyright in publications etc. Users of this classification system should keep in mind that Pharmaceutical markets can be segmented according to numerous criteria." © EphMRA 2021 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 1 B BLOOD AND BLOOD FORMING ORGANS 28 C CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM 36 D DERMATOLOGICALS 51 G GENITO-URINARY SYSTEM AND SEX HORMONES 58 H SYSTEMIC HORMONAL PREPARATIONS (EXCLUDING SEX HORMONES) 68 J GENERAL ANTI-INFECTIVES SYSTEMIC 72 K HOSPITAL SOLUTIONS 88 L ANTINEOPLASTIC AND IMMUNOMODULATING AGENTS 96 M MUSCULO-SKELETAL SYSTEM 106 N NERVOUS SYSTEM 111 P PARASITOLOGY 122 R RESPIRATORY SYSTEM 124 S SENSORY ORGANS 136 T DIAGNOSTIC AGENTS 143 V VARIOUS 145 Anatomical Classification Guidelines V2021 INTRODUCTION The Anatomical Classification was initiated in 1971 by EphMRA. It has been developed jointly by Intellus/PBIRG and EphMRA. It is a subjective method of grouping certain pharmaceutical products and does not represent any particular market, as would be the case with any other classification system. -

![Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.1] European Commission](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2346/ehealth-dsi-ehdsi-v2-2-1-european-commission-2422346.webp)

Ehealth DSI [Ehdsi V2.2.1] European Commission

MTC eHealth DSI [eHDSI v2.2.1] European Commission - Master Translation/Transcoding Catalogue Responsible : eHDSI Solution Provider PublishDate : Thu Jun 01 17:03:48 CEST 2017 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.1 Thu Jun 01 17:03:48 CEST 2017 Page 1 of 490 MTC Table of Contents epSOSActiveIngredient 4 epSOSAdministrativeGender 148 epSOSAdverseEventType 149 epSOSAllergenNoDrugs 150 epSOSBloodGroup 155 epSOSBloodPressure 156 epSOSCodeNoMedication 157 epSOSCodeProb 158 epSOSConfidentiality 159 epSOSCountry 160 epSOSDisplayLabel 167 epSOSDocumentCode 170 epSOSDoseForm 171 epSOSHealthcareProfessionalRoles 184 epSOSIllnessesandDisorders 186 epSOSLanguage 448 epSOSMedicalDevices 458 epSOSNullFavor 461 epSOSPackage 462 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.1 Thu Jun 01 17:03:48 CEST 2017 Page 2 of 490 MTC epSOSPersonalRelationship 464 epSOSPregnancyInformation 466 epSOSProcedures 467 epSOSReactionAllergy 470 epSOSResolutionOutcome 472 epSOSRoleClass 473 epSOSRouteofAdministration 474 epSOSSections 477 epSOSSeverity 478 epSOSSocialHistory 479 epSOSStatusCode 480 epSOSSubstitutionCode 481 epSOSTelecomAddress 482 epSOSTimingEvent 483 epSOSUnits 484 epSOSUnknownInformation 487 epSOSVaccine 488 © eHealth DSI eHDSI Solution Provider v2.2.1 Thu Jun 01 17:03:48 CEST 2017 Page 3 of 490 MTC epSOSActiveIngredient epSOSActiveIngredient Value Set ID 1.3.6.1.4.1.12559.11.10.1.3.1.42.24 TRANSLATIONS Code System ID Code System Version Concept Code Description (FSN) 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 2017-01 A ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM 2.16.840.1.113883.6.73 -

Diccionario Del Sistema De Clasificación Anatómica, Terapéutica, Química - ATC CATALOGO SECTORIAL DE PRODUCTOS FARMACEUTICOS

DIRECCION GENERAL DE MEDICAMENTOS, INSUMOS Y DROGAS - DIGEMID EQUIPO DE ASESORIA - AREA DE CATALOGACION Diccionario del Sistema de Clasificación Anatómica, Terapéutica, Química - ATC CATALOGO SECTORIAL DE PRODUCTOS FARMACEUTICOS CODIGO DESCRIPCION ATC EN CASTELLANO DESCRIPCION ATC EN INGLES FUENTE A TRACTO ALIMENTARIO Y METABOLISMO ALIMENTARY TRACT AND METABOLISM ATC OMS A01 PREPARADOS ESTOMATOLÓGICOS STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS ATC OMS A01A PREPARADOS ESTOMATOLÓGICOS STOMATOLOGICAL PREPARATIONS ATC OMS A01AA Agentes para la profilaxis de las caries Caries prophylactic agents ATC OMS A01AA01 Fluoruro de sodio Sodium fluoride ATC OMS A01AA02 Monofluorfosfato de sodio Sodium monofluorophosphate ATC OMS A01AA03 Olaflur Olaflur ATC OMS A01AA04 Fluoruro de estaño Stannous fluoride ATC OMS A01AA30 Combinaciones Combinations ATC OMS A01AA51 Fluoruro de sodio, combinaciones Sodium fluoride, combinations ATC OMS A01AB Antiinfecciosos y antisépticos para el tratamiento oral local Antiinfectives and antiseptics for local oral treatment ATC OMS A01AB02 Peróxido de hidrógeno Hydrogen peroxide ATC OMS A01AB03 Clorhexidina Chlorhexidine ATC OMS A01AB04 Amfotericina B Amphotericin B ATC OMS A01AB05 Polinoxilina Polynoxylin ATC OMS A01AB06 Domifeno Domiphen ATC OMS A01AB07 Oxiquinolina Oxyquinoline ATC OMS A01AB08 Neomicina Neomycin ATC OMS A01AB09 Miconazol Miconazole ATC OMS A01AB10 Natamicina Natamycin ATC OMS A01AB11 Varios Various ATC OMS A01AB12 Hexetidina Hexetidine ATC OMS A01AB13 Tetraciclina Tetracycline ATC OMS A01AB14 Cloruro de benzoxonio -

Study Protocol Celerion Project No.: CA19169 Aronora Inc

Celerion Project No.: CA19169 Sponsor Project No.: EWE-17-01 US PIND No.: PTS #PS003017; CRMTS #10353 A Phase 1, Single Ascending Dose, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study to Evaluate the Safety, Tolerability, and Pharmacodynamics of E-WE Thrombin as an Intravenous Bolus in Healthy Adult Subjects GCP Statement This study is to be performed in full compliance with the protocol, Good Clinical Practices (GCP), and applicable regulatory requirements. All required study documentation will be archived as required by regulatory authorities. Confidentiality Statement This document is confidential. It contains proprietary information of Aronora Inc., and/or Celerion. Any viewing or disclosure of such information that is not authorized in writing by Aronora Inc., and/or Celerion is strictly prohibited. Such information may be used solely for the purpose of reviewing or performing this study. CA19169 (EWE-17-01) Final Protocol Amendment 2 14May2018 E-WE Thrombin Page 2 Sponsor Project No.: EWE-17-01 SAD Study Protocol Celerion Project No.: CA19169 Aronora Inc. US PIND No.: PTS #PS003017; CRMTS #10353 1. PROTOCOL REVISION HISTORY DATE/NAME DESCRIPTION 14May2018 Final Protocol, Amendment 2: by Caroline Engel Following on FDA recommendations, the following changes were made to the protocol: 1. The dosing interval between the sentinel group and the remaining subjects was revised to at least 28 days in Cohort 1 and 14 days in the remaining cohorts. The protocol was updated throughout to reflect this change. 2. The following study stopping rules were added to bullet number 5 in Section 10.4.1.4 Dose Escalation and Stopping Rules: I. -

WO 2013/170195 Al 14 November 2013 (14.11.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/170195 Al 14 November 2013 (14.11.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, A61L 24/04 (2006.01) A61K 9/127 (2006.01) KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, (21) International Application Number: NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, PCT/US20 13/0406 19 RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (22) International Filing Date: TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, 10 May 2013 (10.05.2013) ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 61/646,227 11 May 2012 ( 11.05.2012) TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, 61/669,577 9 July 2012 (09.07.2012) EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, 61/785,358 14 March 2013 (14.03.2013) MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, (71) Applicant: MEDICUS BIOSCIENCES, LLC [US/US]; ML, MR, NE, SN, TD, TG). -

Malaysian Statistics on MEDICINES-271010.Indd

MALAYSIAN STATISTICS ON MEDICINES 2007 CHAPTER 7 | USE OF ANTIHAEMORRHAGICS Lim Y.S.1, Wong S.P.1, Goh A.S.2, Chang K.M.1 1. Ampang Hospital, 2. Pulau Pinang Hospital Antihaemorrhagics did not differ much in usage trends from 2006 to 2007. The most used class of antihaemorrhagics was still the class of amino acids, namely tranexamic acid (0.07 DDD/1000 population/day), owing to its safety profile, readily available forms as capsules and injection ampoules as well as cheap price. Tranexamic acid was used for local fibrinolysis and menorrhagia. The Australian data showed a higher consumption for tranexamic acid with 0.11 DDD/1000 population/day in 2007.1 Aprotinin, a proteinase inhibitor (0.0003 DDD/1000 population/ day), was indicated for the reduction or prevention of blood loss in patients undergoing open heart surgeries only.2 Aprotinin was apparently more used in the private sector than in the public sector as so happened in reality. Although recombinant Factor VIIa or eptacog alfa (activated) was one of the few agents available for haemophilia A or B patients with inhibitors to coagulation factors VIII or IX, recent years had seen it being used in excessive bleeding incidences unmanageable by conservative treatments or blood coagulation factors during minor or major surgical even critical neuro-surgical or obstetrics-gynaecological procedures.3 However, its overall usage was still very minimal at 0.0001 DDD/1000 population/day, perhaps due to its exorbitant price tag of ~RM 2700 per vial of 1.2mg. The length of stay in critically ill patients that need reversal of coagulopathy and the costs of hospitalisation should be added to the total charges that would count to the cost-effectiveness of eptacog alfa.4 In fact, eptacog alfa (activated) was little used in both sectors of the healthcare industry. -

Germany Haemotherapy Guidelines

Bundesärztekammer (German Medical Association) Cross-sectional Guidelines for Therapy with Blood Components and Plasma Derivatives Published by: Executive Committee of the German Medical Association on the recommendation of the Scientific Advisory Board 4th revised edition ii Notice: Medical science and the public health service are subject to continuous development, entailing that all statements regarding them can only be in accordance with the state of knowledge current at the time of publication. The utmost care was taken by the authors in compiling and verifying the stated recommendations. Despite diligent manuscript preparation and proof-reading of the typeset, occasional mistakes cannot be ruled out with certainty. Regarding the choice and dosage of drugs, the reader is requested to consult the manufacturer’s package insert and expert information and, in case of doubt, to draw on a specialist. Liability for any diagnostic or therapeutic application, medication or dosage lies with the reader. Accordingly, the German Medical Association does not assume responsibility and no subsequent or any other damage that result in any way from the use of information contained in this publication. This publication is copyright-protected. Any unauthorized use therefore requires prior written permission from the German Medical Association. Copyright © 2009 by German Medical Association iii This English translation and printing of the Cross-sectional Guidelines was funded by the organisers of the European Symposium on “Optimal Clinical Use of Blood Components”, April 24th–25th 2009, Wildbad Kreuth, Germany (European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines & Health Care, Strasbourg; LMU Klinikum der Universität, München; Paul- Ehrlich-Institut, Langen). The organisers gratefully acknowledge the excellent translation by Ms. -

Antifibrinolytic Drugs for Treating Primary Postpartum Haemorrhage (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage (Review) Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, Gayet-Ageron A, Ker K, Mousa HA Shakur H, Beaumont D, Pavord S, Gayet-Ageron A, Ker K, Mousa HA. Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD012964. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD012964. www.cochranelibrary.com Antifibrinolytic drugs for treating primary postpartum haemorrhage (Review) Copyright © 2018 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 7 METHODS ...................................... 7 Figure1. ..................................... 10 RESULTS....................................... 14 Figure2. ..................................... 16 Figure3. ..................................... 17 DISCUSSION ..................................... 21 Figure4. ..................................... 23 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 23 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 23 REFERENCES ..................................... 24 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 27 DATAANDANALYSES. 38 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Standard care plus IV tranexamic acid versus placebo or standard care alone for the treatment of PPH, Outcome 1 Maternal mortality due -

Antifibrinolytic Drugs for Acute Traumatic Injury (Review)

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury (Review) Ker K, Roberts I, Shakur H, Coats TJ Ker K, Roberts I,Shakur H, CoatsTJ. Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD004896. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004896.pub4. www.cochranelibrary.com Antifibrinolytic drugs for acute traumatic injury (Review) Copyright © 2015 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. TABLE OF CONTENTS HEADER....................................... 1 ABSTRACT ...................................... 1 PLAINLANGUAGESUMMARY . 2 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS FOR THE MAIN COMPARISON . ..... 4 BACKGROUND .................................... 6 OBJECTIVES ..................................... 6 METHODS ...................................... 7 RESULTS....................................... 8 Figure1. ..................................... 9 Figure2. ..................................... 11 ADDITIONALSUMMARYOFFINDINGS . 15 DISCUSSION ..................................... 18 AUTHORS’CONCLUSIONS . 19 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . 19 REFERENCES ..................................... 19 CHARACTERISTICSOFSTUDIES . 21 DATAANDANALYSES. 30 Analysis 1.1. Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 1 All-cause mortality. 31 Analysis 1.2. Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 2 Myocardial infarction. 32 Analysis 1.3. Comparison 1 Antifibrinolytics versus control (all trauma), Outcome 3 Stroke. 32 Analysis 1.4. Comparison