Surgery for Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons' Clinical Practice

CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINES The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons’ Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Constipation Ian M. Paquette, M.D. • Madhulika Varma, M.D. • Charles Ternent, M.D. Genevieve Melton-Meaux, M.D. • Janice F. Rafferty, M.D. • Daniel Feingold, M.D. Scott R. Steele, M.D. he American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons for functional constipation include at least 2 of the fol- is dedicated to assuring high-quality patient care lowing symptoms during ≥25% of defecations: straining, Tby advancing the science, prevention, and manage- lumpy or hard stools, sensation of incomplete evacuation, ment of disorders and diseases of the colon, rectum, and sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage, relying on anus. The Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee is com- manual maneuvers to promote defecation, and having less posed of Society members who are chosen because they than 3 unassisted bowel movements per week.7,8 These cri- XXX have demonstrated expertise in the specialty of colon and teria include constipation related to the 3 common sub- rectal surgery. This committee was created to lead inter- types: colonic inertia or slow transit constipation, normal national efforts in defining quality care for conditions re- transit constipation, and pelvic floor or defecation dys- lated to the colon, rectum, and anus. This is accompanied function. However, in reality, many patients demonstrate by developing Clinical Practice Guidelines based on the symptoms attributable to more than 1 constipation sub- best available evidence. These guidelines are inclusive and type and to constipation-predominant IBS, as well. The not prescriptive. -

OT Resource for K9 Overview of Surgical Procedures

OT Resource for K9 Overview of surgical procedures Prepared by: Hannah Woolley Stage Level 1 2 Gynecology/Oncology Surgeries Lymphadenectomy (lymph node dissection) Surgical removal of lymph nodes Radical: most/all of the lymph nodes in tumour area are removed Regional: some of the lymph nodes in the tumour area are removed Omentectomy Surgical procedure to remove the omentum (thin abdominal tissue that encases the stomach, large intestine and other abdominal organs) Indications for omenectomy: Ovarian cancer Sometimes performed in combination with TAH/BSO Posterior Pelvic Exenteration Surgical removal of rectum, anus, portion of the large intestine, ovaries, fallopian tubes and uterus (partial or total removal of the vagina may also be indicated) Indications for pelvic exenteration Gastrointestinal cancer (bowel, colon, rectal) Gynecological cancer (cervical, vaginal, ovarian, vulvar) Radical Cystectomy Surgical removal of the whole bladder and proximal lymph nodes In men, prostate gland is also removed In women, ovaries and uterus may also be removed Following surgery: Urostomy (directs urine through a stoma on the abdomen) Recto sigmoid pouch/Mainz II pouch (segment of the rectum and sigmoid colon used to provide anal urinary diversion) 3 Radical Vulvectomy Surgical removal of entire vulva (labia, clitoris, vestibule, introitus, urethral meatus, glands/ducts) and surrounding lymph nodes Indication for radical vulvectomy Treatment of vulvar cancer (most common) Sentinel Lymph Node Dissection (SLND) Exploratory procedure where the sentinel lymph node is removed and examined to determine if there is lymph node involvement in patients diagnosed with cancer (commonly breast cancer) Total abdominal hysterectomy/bilateral saplingo-oophorectomy (TAH/BSO) Surgical removal of the uterus (including cervix), both fallopian tubes and ovaries Indications for TAH/BSO: Uterine fibroids: benign growths in the muscle of the uterus Endometriosis: condition where uterine tissue grows on structures outside the uterus (i.e. -

Information for Patients Having a Sigmoid Colectomy

Patient information – Pre-operative Assessment Clinic Information for patients having a sigmoid colectomy This leaflet will explain what will happen when you come to the hospital for your operation. It is important that you understand what to expect and feel able to take an active role in your treatment. Your surgeon will have already discussed your treatment with you and will give advice about what to do when you get home. What is a sigmoid colectomy? This operation involves removing the sigmoid colon, which lies on the left side of your abdominal cavity (tummy). We would then normally join the remaining left colon to the top of the rectum (the ‘storage’ organ of the bowel). The lines on the attached diagram show the piece of bowel being removed. This operation is done with you asleep (general anaesthetic). The operation not only removes the bowel containing the tumour but also removes the draining lymph glands from this part of the bowel. This is sent to the pathologists who will then analyse each bit of the bowel and the lymph glands in detail under the microscope. This operation can often be completed in a ‘keyhole’ manner, which means less trauma to the abdominal muscles, as the biggest wound is the one to remove the bowel from the abdomen. Sometimes, this is not possible, in which case the same operation is done through a bigger incision in the abdominal wall – this is called an ‘open’ operation. It does take longer to recover with an open operation but, if it is necessary, it is the safest thing to do. -

Laparoscopic Hand-Sewn Duodenal Switch. Video

Baltasar A., BMI-2012, 2.1.4 (11-13) February 2012 OA Laparoscopic Hand-sewn Duodenal Switch. Video Aniceto Baltasar, *Rafael Bou, Marcelo Bengochea, *Carlos Serra, *Nieves Pérez San Jorge Clinic and *Hospital “Virgen de los Lirios”. Cid 61.Alcoy. Alicante. Spain. Phone (0034) 965.332.536. [email protected] Key Words: Laparoscopic Duodenal Switch; Bilio Pancreatic Diversion; Gastric Sleeve; Obesity surgery Introduction The Duodenal Switch (DS) is one alternative to the Scopinaro Bilio-Pancreatic Diversion (BPD). Hess [1] performed the first open case in March 1988 (in a male BMI-60 and he was BMI-29 17 years later) and Marceau [2] made the first publication. Baltasar [3.4] increased the statistics. Rabkin [5] performed the first Fig.1. LapDS Fig.2. Ports positions Lap DS (LDS) hand-assisted for the duodeno-ileum anastomosis in August 1999, Gagner [6] the first fully LDS in September the same year and Baltasar [7.8] published the second world experience. Three surgeons perform the operation SA is in between the legs, SB in on the right side and SC on the LDS consist of 1) Vertical Gastric Sleeve (VGS) with right side through 6 ports. Direct vision approach is pyloric preservation of less than 60 cc and 2) A BPD always used for the first port (1P) with an Ethicon with a Common Channel (CC) of 65-100 cm, an Endopath#12 on the lateral border of the right rectus Alimentary Loop (AL) of 235-300 cm and the muscle, 3-4 fingerbreadths below the right costal remaining Bilio-Pancreatic Loop (BPL) as the margin. -

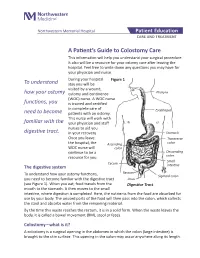

A Patient's Guide to Colostomy Care

Northwestern Memorial Hospital Patient Education CARE AND TREATMENT A Patient’s Guide to Colostomy Care This information will help you understand your surgical procedure. It also will be a resource for your ostomy care after leaving the hospital. Feel free to write down any questions you may have for your physician and nurse. During your hospital Figure 1 To understand stay you will be visited by a wound, how your ostomy ostomy and continence Pharynx (WOC) nurse. A WOC nurse functions, you is trained and certified in complete care of Esophagus need to become patients with an ostomy. This nurse will work with familiar with the your physician and staff nurses to aid you digestive tract. in your recovery. Stomach Once you leave Transverse the hospital, the Ascending colon WOC nurse will colon continue to be a Descending resource for you. colon Small Cecum The digestive system intestine Rectum To understand how your ostomy functions, Sigmoid colon you need to become familiar with the digestive tract Anus (see Figure 1). When you eat, food travels from the Digestive Tract mouth to the stomach. It then moves to the small intestine, where digestion is completed. Here, the nutrients from the food are absorbed for use by your body. The unused parts of the food will then pass into the colon, which collects the stool and absorbs water from the remaining material. By the time this waste reaches the rectum, it is in a solid form. When the waste leaves the body, it is called a bowel movement (BM), stool or feces. -

Mucocele of the Appendix - Appendectomy Or Colectomy?

Original Article Mucocele of the appendix - appendectomy or colectomy? JANDUÍ GOMES DE ABREU FILHO1, ERIVALDO FERNANDES DE LIRA1 1Service of Coloproctology of Hospital de Base do Distrito Federal (HBDF), Secretariat of Health in Distrito Federal - Brasília (DF), Brazil. FILHO JGDA; LIRA EFD. Mucocele of the appendix - appendectomy or colectomy? Rev bras Coloproct, 2011;31(3): 276-284. ABSTRACT: Mucocele of the appendix is a rare disease. It can be triggered by benign or malignant diseases, which cause the obstruc- tion of the appendix and the consequent accumulation of mucus secretion. The preoperative diagnosis is difficult due to non-specific clinical manifestations of the disease. Imaging tests can suggest the diagnosis. The treatment is always surgical and depends on the integrity and size of the appendix base and on the histological type of the original lesion. The prognosis is good in cases of integrity of the appendix. The perforation of the appendix and subsequent extravasation of its contents into the abdominal cavity may lead to pseudomyxoma peritonei, which has very poor prognosis if not treated properly. Keywords: mucocele; appendix; pseudomyxoma peritonei; treatment. INTRODUCTION first one defends the right colectomy as a treatment9, and the second one recommends only appendecto- The mucocele of the appendix was first de- my10. Despite the different adopted conducts, in both scribed in 1842 by Rokitansky1. This disease is reported cases a cystadenoma was diagnosed in the considered as a rare lesion of the appendix, which appendix; the choice was for elective surgery. is found in 0.2 to 0.3% of the appendectomies2. It The objective of this review is to analyze liter- is characterized by the dilation of the organ lumen ature as to mucocele, especially regarding diagnosis with mucus accumulation, being more frequent and treatment, besides discussing follow-up and prog- among individuals aged 50 years or more3,4. -

Direct Oral Anticoagulants Use in the Setting of Bariatric Surgery and Feeding Tubes Excellence.Acforum.Org

Rapid Resource Direct Oral Anticoagulants Use in the Setting of Bariatric Surgery and Feeding Tubes excellence.acforum.org ACE Rapid Resources are not informed practice guidelines; they are Anticoagulation Forum, Inc.’s best recommendations based on (DOACs) NOTES current knowledge, and no warranty or guaranty is expressed or implied. The content provided is for informational purposes for medical • DOACs are absorbed at various professionals only and is not intended to be used or relied upon by them as specific medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment, the locations throughout the determination of which remains the responsibility of the medical professionals for their patients. gastrointestinal tract. Bariatric Surgery (See Table 1) • Bariatric surgery results in weight FIGURE 1 – Types of Bariatric Surgery loss by reducing stomach volume (which results in a more alkaline pH) A B C D and/or reducing effective intestinal surface area which results in malabsorption. • There is very little evidence regarding safety and efficacy of DOACs in patients with a history of bariatric surgery or requiring DOAC administration via a feeding tube. A. Adjustable gastric banding (AGB): Adjustable silicone band placed around stomach to create a smaller pouch. • This document was compiled utilizing current literature incorporating case B. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB): reports, package inserts, and Stomach stapled to form gastric pouch that connects to distal jejunum, excluding the duodenum and proximal jejunum. pharmacokinetic studies as no current C. Gastrectomy (partial or total): randomized controlled trials are Sleeve gastrectomy results in longitudinal resection of 80% of stomach. available. As always, clinical judgment D. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch (BPD-DS): and a shared decision making Gastric pouch reattached more distally to terminal ileum resulting in considerable reduction in absorptive surface approach should be utilized. -

Hybrid Procedure Offers a Less Invasive Alternative to Colectomy

The better way to get better Hybrid procedure offers a less invasive alternative to colectomy Insufflation gas provides important advantage The colonoscopy-laparoscopy procedure is made possible through the combined skills of the gastroenterologist and laparoscopic surgeon, and the use of CO2 rather than ambient air for insufflation — the introduction of gas into the colon to improve visibility. CO2 is more quickly absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract and results in less bowel distension, giving the laparoscopic surgeon a better field of vision within the abdominal cavity. © Copyright Olympus. Used with permission. “Some patients who would have required a bowel resection can instead benefit from this A new, minimally invasive procedure that is a hybrid of colonoscopy and less invasive procedure. We’re laparoscopy is proving to be a safe and effective alternative to open colectomy using this combined technique (removal of part of the colon) for patients with benign colon polyps that are as a way for patients to avoid colectomy,” explains James not removable endoscopically. Yoo, M.D., a colorectal surgeon Patients who undergo this hybrid procedure experience less pain and often go at UCLA. “This procedure home after only one or two days. Scarring and wound complications are minimal involves tiny incisions for the as the laparoscopic surgeon makes only small, keyhole incisions in the abdomen laparoscopic instruments and patients stay in the hospital only rather than the long incision characteristic of a traditional colectomy. a day or two.” WWW.UCLAHEALTH.ORG 1-800-UCLA-MD1 (1-800-825-2631) Who can benefit from the procedure? Participating When a routine colonoscopy reveals polyps, they are usually removed at the Physicians time of the procedure as a precaution against their progression to cancer. -

ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding

nature publishing group PRACTICE GUIDELINES 1265 CME ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Small Bowel Bleeding L a u r e n B . G e r s o n , M D , M S c , F A C G1 , J e ff L. Fidler , MD 2 , D a v i d R . C a v e , M D , P h D , F A C G 3 a n d J o n a t h a n A . L e i g h t o n , M D , F A C G 4 Bleeding from the small intestine remains a relatively uncommon event, accounting for ~5–10% of all patients presenting with gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. Given advances in small bowel imaging with video capsule endoscopy (VCE), deep enteroscopy, and radiographic imaging, the cause of bleeding in the small bowel can now be identifi ed in most patients. The term small bowel bleeding is therefore proposed as a replacement for the previous classifi cation of obscure GI bleeding (OGIB). We recommend that the term OGIB should be reserved for patients in whom a source of bleeding cannot be identifi ed anywhere in the GI tract. A source of small bowel bleeding should be considered in patients with GI bleeding after performance of a normal upper and lower endoscopic examination. Second-look examinations using upper endoscopy, push enteroscopy, and/or colonoscopy can be performed if indicated before small bowel evaluation. VCE should be considered a fi rst-line procedure for small bowel investigation. Any method of deep enteroscopy can be used when endoscopic evaluation and therapy are required. -

42 CFR Ch. IV (10–1–12 Edition) § 410.35

§ 410.35 42 CFR Ch. IV (10–1–12 Edition) the last screening mammography was (1) Colorectal cancer screening tests performed. means any of the following procedures furnished to an individual for the pur- [59 FR 49833, Sept. 30, 1994, as amended at 60 FR 14224, Mar. 16, 1995; 60 FR 63176, Dec. 8, pose of early detection of colorectal 1995; 62 FR 59100, Oct. 31, 1997; 63 FR 4596, cancer: Jan. 30, 1998] (i) Screening fecal-occult blood tests. (ii) Screening flexible § 410.35 X-ray therapy and other radi- sigmoidoscopies. ation therapy services: Scope. (iii) In the case of an individual at Medicare Part B pays for X-ray ther- high risk for colorectal cancer, screen- apy and other radiation therapy serv- ing colonoscopies. ices, including radium therapy and ra- (iv) Screening barium enemas. dioactive isotope therapy, and mate- (v) Other tests or procedures estab- rials and the services of technicians ad- lished by a national coverage deter- ministering the treatment. mination, and modifications to tests [51 FR 41339, Nov. 14, 1986. Redesignated at 55 under this paragraph, with such fre- FR 53522, Dec. 31, 1990] quency and payment limits as CMS de- termines appropriate, in consultation § 410.36 Medical supplies, appliances, with appropriate organizations and devices: Scope. (2) Screening fecal-occult blood test (a) Medicare Part B pays for the fol- means— lowing medical supplies, appliances (i) A guaiac-based test for peroxidase and devices: activity, testing two samples from (1) Surgical dressings, and splints, each of three consecutive stools, or, casts, and other devices used for reduc- (ii) Other tests as determined by the tion of fractures and dislocations. -

Double Barrel Wet Colostomy for Urinary and Fecal Diversion

Open Access Clinical Image J Urol Nephrol November 2017 Vol.:4, Issue:2 © All rights are reserved by Kang,et al. Journal of Double Barrel Wet Colostomy for Urology & Urinary and Fecal Diversion Nephrology Yu-Hao Xue and Chih-Hsiung Kang* Keywords: Double barrel wet colostomy; Urinary diversion; Fecal Department of Urology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital-Kaohsiung diversion Medical Center, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, Republic of China Abstract Address for Correspondence A 60-year-old male who had a history of spinal cord injury received Chih-Hsiung Kang, Department of Urology, Chang Gung Memorial loop colostomy for fecal diversion and cystostomy for urinary diversion. Hospital - Kaohsiung Medical Center, Chang Gung University College Because he was diagnosed with muscle invasive bladder cancer, of Medicine, Taiwan, E- mail: [email protected] radical cystectomy and double barrel wet colostomy was conducted. Submission: 30 October, 2017 Computed tomography showed simultaneous urinary and fecal Accepted: 06 November, 2017 diversion and stone formation in the distal segment of colon conduit Published: 10 November, 2017 with urinary diversion. Copyright: © 2017 Kang CH, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, Introduction provided the original work is properly cited. In patients with an advanced primary or recurrent carcinoma, double-barreled wet colostomy can be used for pelvic exenteration Bilateral hydroureters and mild hydronephrosis were noted and and urinary tract reconstruction. It is a technique that separate we suspected the calculi impacted in bilateral ureteto-colostomy urinary and fecal diversion with a single abdominal stoma. -

The Role of Growth Hormone in Adaptation to Massive Small Intestinal Resection in Rats

0031-3998/01/4902-0189 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Vol. 49, No. 2, 2001 Copyright © 2001 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Printed in U.S.A. The Role of Growth Hormone in Adaptation to Massive Small Intestinal Resection in Rats MICHAEL DURANT, SHARRON E. GARGOSKY, K. ANDERS DAHLSTROM, RIXUN FANG, BARRY H. HELLMAN, JR., AND RICARDO O. CASTILLO Department of Pediatrics [M.D., S.E.G., R.F., R.O.C.], Department of Pathology [B.H.H.], and the Digestive Disease Center [R.O.C.], Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, U.S.A.; and Department of Pediatrics, Huddinge Hospital, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden [K.A.D.] ABSTRACT The residual small bowel undergoes profound adaptive alter- alterations in processing of digestive hydrolases of the distal ations after surgical resection. GH is considered to have a role in intestine, indicating that GH may have region-specific effects on regulation of these adaptive changes, but its precise role is small intestinal function. We conclude that GH is required for the unknown. We investigated the role of GH by studying the normal expression of specific components of the adaptive re- response to intestinal resection in rats with isolated GH defi- sponse to massive small intestinal resection, but not for all ciency. Spontaneous dwarf rats, a strain of rats with congenital aspects. The aspects that require GH appear to involve protein isolated GH deficiency, underwent 60% resection of the small synthesis and processing. (Pediatr Res 49: 189–196, 2001) intestine and parameters of the response of the intestinal remnant were compared with age-matched GH-deficient rats undergoing Abbreviations: transection, GH-normal rats undergoing 60% resection, and non- SDR, spontaneous dwarf rats manipulated GH-normal rats.