Ken Bousfield (416) 957 1650

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ests Under Canadian Patent Law: Useful Or Not?

Canadian Journal of Law and Technology Volume 5 Number 2 Article 2 4-1-2006 ESTs under Canadian Patent Law: Useful or Not? Natalie C. Bellefeuille Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cjlt Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Natalie C. Bellefeuille, "ESTs under Canadian Patent Law: Useful or Not?" (2006) 5:2 CJLT. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Journal of Law and Technology by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESTs under Canadian Patent Law: Useful or Not? Natalie C. Bellefeuille† Introduction one of the two cDNA strands: a 5’ EST is obtained when the beginning portion of a cDNA is sequenced, whereas a 3’ EST is obtained when the ending portion of a cDNA The Debate is sequenced. 9 ESTs thus represent short DNA sequences, the majority of which encode part of a gene, but rarely a he patentability of human genetic material has full-length gene. As will be discussed in greater detail T given rise to considerable debate around the below, they are generally only useful to researchers as 1 world. As Kevles notes, ‘‘[o]ne of the most controversial tools to identify the full-length gene, and rarely provide issues in biotechnology in the Unites States and Europe information about the function or location of the gene. -

Expert Report of Professor Norman V. Siebrasse

In the Arbitration under the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and the North American Free Trade Agreement (Case No. UNCT/14/2) ELI LILLY AND COMPANY Claimant v. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent EXPERT REPORT OF PROFESSOR NORMAN V. SIEBRASSE Professor of Law, University of New Brunswick TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 3 A. Background and Qualifications........................................................................................... 3 B. Overview of Patent Law in Canada .................................................................................... 3 (i) Purpose of Patent Rights ................................................................................................. 3 (ii) Patentability Requirements ......................................................................................... 4 (iii) Claims and Disclosure ................................................................................................ 4 II. Law of Utility In Canada ........................................................................................................ 6 A. Overview ............................................................................................................................. 6 B. Utility At Date of Filing/Examination of Zyprexa and Strattera Patents............................ 7 (i) Utility Standard .............................................................................................................. -

Expert Report of Professor Robert P. Merges the University of California, Berkeley, School of Law

In the Arbitration under the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law and the North American Free Trade Agreement (Case No. UNCT/14/2) ELI LILLY AND COMPANY Claimant v. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA Respondent Expert Report of Professor Robert P. Merges The University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Table of Contents I. Background and Qualifications ................................................................................................. 3 II. Summary of Conclusions ............................................................................................................. 3 III. Overview of U.S. Patent Law .................................................................................................. 5 A. U.S. Patentability Requirements .......................................................................................... 5 B. Utility: The Standard of Operability ................................................................................... 8 C. Purpose of U.S. Utility Doctrine ......................................................................................... 12 IV. Comparing the Canadian “Promise Doctrine” to U.S. Law on Utility .................. 15 A. The Utility of the Strattera and Zyprexa Patents ........................................................ 15 B. The Cost of the Promise Doctrine ..................................................................................... 20 V. Conclusion ..................................................................................................................................... -

Fox on the Canadian Law of Patents, 5Th Edition

Fox on The Canadian Law of Patents, 5th Edition August 1, 2013 By Donald H. MacOdrum Bereskin & Parr is pleased to announce the publication of Fox on The Canadian Law of Patents, 5th Ed., authored by Donald H. MacOdrum, one of Canada’s most respected and experienced intellectual property practitioners. Fox on The Canadian Law of Patents, published by Carswell, provides a complete overview of Canadian patent law, including authoritative commentary, indispensable guidance and practical insight. Fox on The Canadian Law of Patents is the preeminent reference work for patent lawyers and agents in Canada. This book includes insightful commentary on a wide range of topics, including: invention; obviousness; novelty; utility; patent specification; construction and application; international patent protection including the Patent Cooperation Treaty; the patent grant and validity of patents; re-issue, disclaimer, correction, dedication and re-examination; infringement and remedies for infringement. Donald MacOdrum is a partner in Bereskin & Parr LLP’s Litigation practice group. His practice focuses on intellectual property litigation, which he has practiced for over 40 years. He is recognized as one of the leading patent and patent litigation lawyers in Canada and was the only Canadian ranked in the Intellectual Property category in The BTI Client Service All-Star Team for Law Firms 2013. Click here for more information. Content shared on Bereskin & Parr’s website is for information purposes only. It should not be taken as legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, please contact a Bereskin & Parr LLP professional. We will be pleased to help you. Bereskin & Parr LLP | bereskinparr.com. -

The Presumption of Validity in Canadian Patent Law

NOTES The Presumption of Validity in Canadian Patent Law The role of the presumption in our legal system can best be understood in the light of the fact-finding process, for it permits a party to prove to the court facts crucial to his case merely by establishing the existence of other facts, from which the court will deduce the existence of the primary facts which he alleges. Article 1349 of the Code Napolgon provides that: Les pr6somptions sont des consequences que la loi on le magistrat tire d'un fait connu h un fait inconnu. The implications of this definition' are important, for they indicate that, in strict legal terms, it is not proper to speak of presumptions with respect to a question of law. On the contrary, the term "presumption" is by definition confined to the fact-finding process. Although it follows from this line of reasoning that section 48 of the Patent Act 2 does not create a presumption in favour of a patentee since the issue as to the validity of a patent is ultimately a question of law and one for the courts to decide, there is no doubt that the section, by providing that the patent is "prima facie valid", places a burden upon a litigant challenging the right of the patentee. At the outset, it must be emphasized that the term "presumption" will be used throughout this note in its conventional sense as opposed to its narrow legal meaning. That is to say, the term will indicate that, when it applies, a presumption has the effect of placing upon one party an onus which he would otherwise not have to bear, and, conversely, alleviating the burden of the person opposing him. -

The Right to Repair Doctrine and the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Canadian Patent Law

Canadian Journal of Law and Technology Volume 14 Number 2 Article 2 6-1-2016 The Right to Repair Doctrine and the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Canadian Patent Law Tesh W. Dagne Gosia Piasecka Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.schulichlaw.dal.ca/cjlt Part of the Computer Law Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Internet Law Commons, Privacy Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Tesh W. Dagne and Gosia Piasecka, "The Right to Repair Doctrine and the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Canadian Patent Law" (2016) 14:2 CJLT. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Schulich Law Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Journal of Law and Technology by an authorized editor of Schulich Law Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Right to Repair Doctrine and the Use of 3D Printing Technology in Canadian Patent Law Tesh W. Dagne and Gosia Piasecka* Abstract 3D printing technology is part of a new economic movement, termed the sharing economy, where consumers rely less on large corporations for supplying them with products. The technology allows consumers to bypass the traditional manufacturing process. Instead, consumers increasingly share and sell products to each other on online sharing platforms. Consumers can download digital copies of products and print them in the convenience of their homes. In addition, they can repair and modify these products to suit their needs. Canadian patent law permits the repair of a patent-protected item but prohibits its reconstruction. -

Bibliothèque – Bibliothek – Biblioteca – Library

1 Bibliothèque – Bibliothek – Biblioteca – Library Acquisitions récentes – Neuanschaffungen – Acquisizioni recenti – Recent acquisitions 09/2018 ISDC — Dorigny — 1015 Lausanne — Suisse — tél. +41 (0) 21 6924911 — fax +41 (0) 21 6924949 — www.isdc.ch — [email protected] 2 A 7.4 a FOUL 1991 Foulquié, Paul. - Dictionnaire de la langue pédagogique / Paul Foulquié. - Paris : Presses universitaires de France, 2018. - VIII, 492 p. ; 19 cm. - (Quadrige ; 125). – Repr. de l’éd. de : Paris : Presses universitaires de France, 1991. - ISBN 2-13-043789-3. R008849553 IF ISDC Libre-accès * Classif.: A 7.4 a FOUL 1991 * Cote: ISDC 196731 A 15.1 g BECK 2007 Rechtswissenschaft und Rechtsliteratur im 20. Jahrhundert : mit Beiträgen zur Entwicklung des Verlages C.H. Beck / hrsg. von Dietmar Willoweit. - München : C.H. Beck, 2007. - 1264 p. : ill. - Mélanges dédiés à Hans Dieter Beck à l'occasion de son 75e anniversaire. - ISBN 9783406558207. R004510472 IF ISDC Libre-accès * Classif.: A 15.1 g BECK 2007 * Cote: ISDC 196698 A 15.1 g BOUV 2014 Histoire, peuple et droit : mélanges offerts au professeur Jacques Bouveresse / textes réunis par Gilduin Davy, Raphaël Eckert et Virginie Lemonnier-Lesage. - Mont-Saint-Aignan : Presses universitaires de Rouen et du Havre, 2014. - 287 p. - ISBN 9791024003412. R008030609 IF ISDC Libre-accès * Classif.: A 15.1 g BOUV 2014 * Cote: ISDC 196819 A 15.1 g DAUD 2014 70 ans des Nations Unies : quel rôle dans le monde actuel? : journée d'études en l'honneur du professeur Yves Daudet / sous la dir. de Karine Bannelier-Christakis ... [et al.]. - Paris : A. Pedone, 2014. - 258 p. : ill. -

Lifesigns Life Sciences Legal Trends in Canada

LifeSigns Life Sciences Legal Trends in Canada 2019-2020 Edition Life Sciences Legal Trends in Canada | 3 Table of Contents 1 Message from BLG 2 Message from Canada’s Leading Life Science Associations 3 | Innovative Medicines Canada – Growing 6 | Life Sciences Ontario – Fostering Canada’s Biopharmaceutical Industry a more prosperous Ontario 4 | BIOTECanada 7 | BioTalent Canada – Transforming the bio-economy’s talent innovation 8 Insights from the Life Sciences Team at BLG 9 | Significant Changes are on the Horizon for 25 | Changes to Canada’s Industrial Design Canadian Patent Prosecution Regime – Streamlining & Harmonizing 12 | The Good, The Bad, and The Complicated: the Process Upcoming Changes to Filing Requirements 27 | Cannabis Ship This? The Canadian for Canadian Patent Applications Cannabis Import and Export Regime 15 | Third Party Rights Coming to Canada to under the Cannabis Act Join New Prior User Rights 29 | New Federal Beer Regulations 18 | Consideration of the Obviousness 30 | Digital Health Technologies: Product Framework by the Federal Courts Regulatory and Litigation Developments 20 | Revised Canadian Intellectual Property 33 | Recent Amendments to the Canadian Enforcement Guidelines: Worth a Patent Act Have Come into Force Closer Look 35 | Modernization of Food Regulations 23 | Patent Term Restoration in Canada in Canada 37 | About BLG’s Life Sciences Group 38 | Key Life Sciences Contacts The information contained herein is of a general nature and is not intended to constitute legal advice, a complete statement of the law, or an opinion on any subject. No one should act upon it or refrain from acting without a thorough examination of the law after the facts of a specific situation are considered. -

CIPPIC/CIPP Amicus Brief on Arbitration

Case No. UNCT/14/2 In the Arbitration under Chapter 11 of the North American Free Trade Agreement and the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules BETWEEN: Eli Lilly and Company CLAIMANT/INVESTOR - and - Government of Canada RESPONDENT/PARTY AMICUS CURIAE SUBMISSIONS SAMUELSON-GLUSHKO CANADIAN INTERNET POLICY & PUBLIC INTEREST CLINIC & CENTRE FOR INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY POLICY Samuelson-Glushko Canadian Internet Centre for Intellectual Property Policy Policy & Public Interest Clinic (CIPPIC) (CIPP) University of Ottawa, Faculty of Law, McGill University, Faculty of Law, Common Law Section 3644 Peel Street 57 Louis Pasteur Street Montreal, QC, H3A 1W9 Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5 David Fewer E. Richard Gold Jeremy de Beer Tel: 541-398-6636 Tel: (613) 562-5800 ext. 2558 Fax: (613) 562-5417 Counsel for the Proposed Intervenor Counsel for the Proposed Intervenor TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I. OVERVIEW .................................................................................................................. 1 PART II. ARGUMENT ................................................................................................................ 2 A. Canadian courts have always played a supervisory role over the Patent Office...................................... 2 B. Nothing in NAFTA prohibits Parties’ domestic laws and jurisprudence from evolving. ........................... 5 1. No formal or informal international standards of utility exist. ..................................................... 5 2. NAFTA Chapter 17 does not undermine the natural evolution of the law. -

1 of 9 © 2016-2020 ATMAC Patent Services Ltd. All Rights Reserved

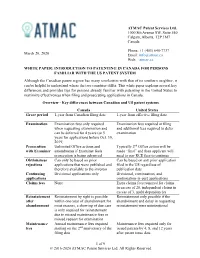

ATMAC Patent Services Ltd. 1000 8th Avenue SW, Suite 550 Calgary, Alberta, T2P 3M7 Canada Phone: +1 (403) 640-7737 March 20, 2020 Email: [email protected] Web: atmac.ca WHITE PAPER: INTRODUCTION TO PATENTING IN CANADA FOR PERSONS FAMILIAR WITH THE US PATENT SYSTEM Although the Canadian patent regime has many similarities with that of its southern neighbor, it can be helpful to understand where the two countries differ. This white paper explains several key differences and provides tips for persons already familiar with patenting in the United States to maximize effectiveness when filing and prosecuting applications in Canada. Overview - Key differences between Canadian and US patent systems Canada United States Grace period 1-year from Canadian filing date 1-year from effective filing date Examination Examination fees only required Examination fees required at filing when requesting examination and and additional fees required to defer can be deferred for 4 years (or 5 examination years for applications before Oct. 30, 2019) Prosecution Unlimited Office actions and Typically 2 nd Office action will be with Examiner amendments if Examiner feels made “final” and then applicant will prosecution is being advanced need to pay RCE fees to continue Obviousness Can only be based on prior Can be based on any prior application rejections applications that were published and filed in the US regardless of therefore available to the inventor publication date Continuing Divisional applications only Divisional, continuation, and applications continuation -

NORMAN SIEBRASSE Professor Faculty of Law University of New Brunswick May 11, 2020

NORMAN SIEBRASSE Professor Faculty of Law University of New Brunswick May 11, 2020 [email protected] Tel: (506) 453-4725 www.SufficientDescription.com Fax: (506) 453-4548 EMPLOYMENT Professor, University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law, July 2006- Present Associate Professor, University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law, July 1999 - June 2006 Assistant Professor, University of New Brunswick Faculty of Law, July 1993 - July 1999 Olin Fellow in Law and Economics, University of Toronto, January - June 1997 Supreme Court of Canada, Law Clerk to Madame Justice Beverley McLachlin, 1991-1992 Schlumberger Oil Field Services, Field Engineer Trainee, October 1985 - April 1986 Bell Northern Research, Hardware Design Engineer, May 1983 - March 1985 EDUCATION LL.M. 1993, The University of Chicago Law School LL.B. 1991, Queen's University, Faculty of Law B.Sc.(Eng. Physics) 1982, Queen's University, Faculty of Engineering Philosophy/ Physics (part time), 1987-88, Queen's University, Faculty of Arts and Science Economics/ Politics, 1982-83, Queen's University, Faculty of Arts and Science PUBLICATIONS —, Liability of Corporate Officers in Intellectual Property Law, Canadian Business Law Journal (forthcoming) Thomas F Cotter, Erik Hovenkamp & —, Demystifying Patent Holdup (2020) 76 Washington and Lee Law Review 1501-65 —, Contributory Infringement in Canadian Law, Canadian Intellectual Property Review (print forthcoming; online) —, Protection Extending Beyond the Language of the Claim: What does Actavis v Lilly Mean for Canadian Law? (Part II) -

To Sell Or Scale Up: Canada's Patent Strategy in a Knowledge Economy

IRPP STUDY August 2019 | No. 72 To Sell or Scale Up: Canada’s Patent Strategy in a Knowledge Economy Nancy Gallini and Aidan Hollis UNLOCKING DEMAND FOR INNOVATION To Sell or Scale Up: Canada’s Patent Strategy in a Knowledge Economy ABOUT THIS STUDY This study was published as part of the Unlocking Demand for Innovation research program, under the direction of Joanne Castonguay and France St-Hilaire. The manu- script was copy- edited by Clare Walker, proofreading was by Barbara Czarnecki, edi- torial coordination was by Francesca Worrall, production was by Chantal Létourneau and art direction was by Anne Tremblay. Nancy Gallini is professor emeritus in the Vancouver School of Economics at the University of British Columbia (UBC). Her research, which has been published in numer- ous peer-reviewed articles, focuses on the economics of intellectual property, technol- ogy licensing and competition policy. She has served on the governing council of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, the Mitacs Research Council, and the editorial boards of the American Economic Review, the Canadian Journal of Economics and other journals in economics. She was dean of the Faculty of Arts at UBC (2002-10), chair of the Department of Economics at the University of Toronto (1995-2000), and president of the Canadian Economic Association (2016-17). Aidan Hollis is professor of economics at the University of Calgary and president of Incen- tives for Global Health, a US-based NGO focused on the development of the Health Im- pact Fund proposal. His research focuses on innovation and competition in pharmaceutical and electricity markets.