Georgia Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Half-Way Mark in This Issue

News from GATES... Half-way Mark In This Issue Half-way Mark Dawn A. Randolph, MPA **************** February 12, 2018 Special Announcements Key Events This Week Week 6 of the session they are meeting Monday - Thursday with Feb 13th as the 20th day of the session, marking the half-way mark of the session. This week we cross the half-way mark Tuesday, February 13th will mark the half-way point of the 40 day session. Remember that the Georgia Constitution requires no more than 40 voting days for the legislature to conduct it's business. These do not need to be consecutive days but days where they are in **************** Chambers casting votes. Tuesday will be day 20 creating a dash to February 28th, or cross over day when all bills must leave one State Use Chamber for consideration by next before the final day of March 29th, Council or sine die. Meeting Thursday, Budget Process March 22nd The full House passed the amended FY 18 budget by a vote 167-8 on 2018 February 6th. The next day the House Human Resources 10:00 AM Appropriations Subcommittee met to hear from agency officials one the Location: Sloppy big budget FY 19. Executive Director Sean Casey of GVRA Floyd Building, emphasized the agencies need to fully match the 110 dollars. The West Tower, current GVRA budget is composed of $21.5 million in state funds to Conference Room draw down about $83 million in 110 federal funds. That leaves about 1816-B, $30 million of federal dollars in Washington. The state would need to invest about $8.2 million to draw down the full federal 110 program 200 Piedmont Ave. -

September 9, 2011 Professional Licensing Board 237 Coliseum Drive Macon, GA 31217

GEORGIA BOARD OF DENTISTRY Board Meeting September 9, 2011 Professional Licensing Board 237 Coliseum Drive Macon, GA 31217 The following Board members were present: Others Present: Dr. Isaac Hadley Reagan Dean, Board Attorney Dr. Clyde Andrews Anita Martin, Executive Director Dr. Becky Carlon Carol White, Board Support Specialist Dr. Richard Bennett, Jr. Melana McClatchey,GDA Dr. Clark Carroll Elizabeth Appley, GDHA Dr. Stephan Holcomb Sid Barrett, Public Health Dr. Logan Nalley Dr. Thomas Duvall Ms. Elaine Richardson Jennie Fleming, GAPH Dr. Barry Stacey Dr. Dwayne Turner, Public Health Dr. Thomas Godfrey Nancy DeMott Janeime Asbury,ADHA Susan Knox Cremering Dr. Elizabeth Lense Pam Wilkes, GDS Dr. John Bowman, GDA Nelda Greene, GDA Tina Titshaw, SDG/HCS Anita LaTourette Jennie Fleming Sid Barrett, Public Health Dr. Thomas Duval Nancy DeMott Janeime Asbury Thomas Brooks Fran Cullen Bill Disque, DVM Dixianne Parker, RDH Rules Committee Meeting The Rules Committee meeting was called to order at 8:38 by Dr. Clyde Andrews Members Present Others Present Dr. Clyde Andrews Elizabeth Appley Dr. Tom Godfrey Nelda Greene, GDA Page 1 of 11 Georgia Board of Dentistry Minutes GEORGIA BOARD OF DENTISTRY Board Meeting September 9, 2011 Professional Licensing Board 237 Coliseum Drive Macon, GA 31217 Dr. Barry Stacey Melana McClatchey Dixia Parker Dr. Thomas Duvall Dr. Dwayne Turner New Rule 150-11-.02 Specialty Licensure was reviewed and tabled for further review. New Rule 150-3-.03 Licensure for Dual Degreed Oral Surgeons was reviewed and tabled for further review. Revisions to Rule 150-3-.09 Continuing Education for Dentists were made. Dr. Stacey motioned for the revised rule to be presented to the Board at its meeting today. -

A Consumer Health Advocate's Guide to the 2017

A CONSUMER HEALTH ADVOCATE’S GUIDE TO THE 2017 GEORGIA LEGISLATIVE SESSION Information for Action 2017 1 2 Contents About Georgians for a Healthy Future » PAGE 2 Legislative Process Overview » PAGE 3 How a Bill Becomes a Law (Chart) » PAGE 8 Constitutional Officers & Health Policy Staff » PAGE 10 Agency Commissioners & Health Policy Staff » PAGE 11 Georgia House of Representatives » PAGE 12 House Committees » PAGE 22 Georgia State Senate » PAGE 24 Senate Committees » PAGE 28 Health Care Advocacy Organizations & Associations » PAGE 30 Media: Health Care, State Government & Political Reporters » PAGE 33 Advocacy Demystified » PAGE 34 Glossary of Terms » PAGE 36 100 Edgewood Avenue, NE, Suite 1015 Atlanta, Georgia 30303 (404) 567-5016 www.healthyfuturega.org ABOUT GEORGIANS FOR A HEALTHY FUTURE Georgians for a Healthy Future (GHF) is a nonprofit health policy and advocacy organiza- tion that provides a voice for Georgia consumers on vital and timely health care issues. Our mission is to build and mobilize a unified voice, vision and leadership to achieve a healthy future for all Georgians. Georgians for a Healthy Future approaches our vision of ensuring access to quality, afford- able health care for all Georgians in three major ways 1) outreach and public education, 2) building, managing, and mobilizing coalitions, and 3) public policy advocacy. GEORGIANS FOR A HEALTHY FUTURE’S 2017 POLICY PRIORITIES INCLUDE: 1. Ensure access to quality, affordable health coverage and care, and protections for all Georgians. 2. End surprise out-of-network bills. 3. Set and enforce network adequacy standards for all health plans in Georgia. 4. Prevent youth substance use disorders through utilizing Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) in Medicaid. -

REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS Reproductive Rights Scorecard Methodology

LEGISLATIVE SCORECARD 2020 REPRODUCTIVE RIGHTS Reproductive Rights Scorecard Methodology Who are we? The ACLU of Georgia envisions a state that guarantees all persons the civil liberties and rights con- tained in the United States and Georgia Constitutions and Bill of Rights. The ACLU of Georgia en- hances and defends the civil liberties and rights of all Georgians through legal action, legislative and community advocacy and civic education and engagement. We are an inclusive, nonpartisan, state- wide organization powered by our members, donors and active volunteers. How do we select the bills to analyze? Which bills did we choose, and why? Throughout the ACLU’s history, great strides To ensure a thorough review of Georgia’s repro- have been made to protect women’s rights, in- ductive justice and women’s rights bills, we scored cluding women’s suffrage, education, women eight bills dating back to 2012. Each legislator entering the workforce, and most recently, the Me was scored on bills they voted on since being elect- Too Movement. Despite this incredible progress, ed (absences and excuses were not counted to- women still face discrimination and are forced to wards the score). Because the bills we chose were constantly defend challenges to their ability to voted on throughout the years of 2012 to 2020, make private decisions about reproductive health. some legislators are scored on a different num- Overall, women make just 78 cents for every ber of bills because they were not present in the dollar earned by men. Black women earn only legislature when every bill scored was voted on or 64 cents and Latinas earn only 54 cents for each they were absent/excused from the vote — these dollar earned by white men. -

Dominion Voting Systems Ballot

**SAMPLE BALLOT** DEKALB COUNTY OFFICIAL ABSENTEE/PROVISIONAL/EMERGENCY BALLOT OFFICIAL REPUBLICAN PARTY PRIMARY AND NONPARTISAN GENERAL ELECTION BALLOT OF THE STATE OF GEORGIA May 19, 2020 To vote, blacken the Oval ( ) next to the candidate of your choice. To vote for a person whose name is not on the ballot, manually WRITE his or her name in the write-in section and blacken the Oval ( ) next to the write- in section. If you desire to vote YES or NO for a PROPOSED QUESTION, blacken the corresponding Oval ( ). Use only blue or black pen or pencil. Do not vote for more candidates than the number allowed for each specific office. Do not cross out or erase. If you erase or make other marks on the ballot or tear the ballot, your vote may not count. If you change your mind or make a mistake, you may return the ballot by writing "Spoiled" across the face of the ballot and return envelope. You may then mail the spoiled ballot back to your county board of registrars, and you will be issued another official absentee ballot. Alternatively, you may surrender the ballot to the poll manager of an early voting site within your county or the precinct to which you are assigned. You will then be permitted to vote a regular ballot. "I understand that the offer or acceptance of money or any other object of value to vote for any particular candidate, list of candidates, issue, or list of issues included in this election constitutes an act of voter fraud and is a felony under Georgia law." [O.C.G.A. -

§¨¦75 §¨¦20 §¨¦85 §¨¦75 §¨¦20 §¨¦85 §¨¦85

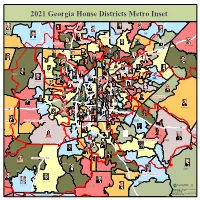

20212021 GeorgiaGeorgia HouseHouse DistrictsDistricts MetroMetro InsetInset Amicalola EMC Lauren McDonald III (R-26) Shrri Gilligan (R-24) Mandi Ballinger (R-23) Mitchell Scoggins (R-14) Emory Dunahoo (R-30) Wes Cantrell (R-22) Hall Cherokee Forsyth Bartow §¨¦985 Sawnee EMC Matthew Gambill (R-15) Jackson Brad Thomas (R-21) Cobb EMC Charlice Byrd (R-20) David Clark (R-98) Tommy Benton (R-31) Todd Jones (R-25) Timothy Barr (R-103) 75 §¨¦ Jan Jones (R-47) §¨¦85 §¨¦575 Jackson EMC John Carson (R-46) Chuck Martin (R-49) Ed Setzler (R-35) Polk Don Parsons (R-44) Bonnie Rich (R-97) Angelika Kausche (D-50) Trey Kelley (R-16) Mary Robichaux (D-48) Gregg Kennard (D-102) Terry England (R-116) Matt Dollar (R-45) Bert Reeves (R-34) Barrow Josh McLaurin (D-51) GwinnettBeth Moore (D-95) Pedro "Pete" Marin (D-96) Samuel Park (D-101) Chuck Efstration (R-104) Ginny Ehrhart (R-36) Paulding Dewey McClain (D-100) Mary Frances Williams (D-37) Martin Momtahan (R-17) §¨¦285 Michael Wilensky (D-79) Cobb Sharon Cooper (R-43) Teri Anulewicz (D-42) Shelly Hutchinson (D-107) Donna McLeod (D-105) Joseph Gullett (R-19) Shea Roberts (D-52) Marvin Lim (D-99) Michael Smith (D-41) Scott Holcomb (D-81) Matthew Wilson (D-80) David Wilkerson (D-38) Jasmine Clark (D-108) Erick Allen (R-40) Rebecca Mitchell (D-106) Betsy Holland (D-54) Tom Kirby (R-114) Billy Mitchell (D-88) Karen Bennett (D-94) Mary Margaret Oliver (D-82) Earnest "Coach" Williams (D-87) Walton EMC Sheila Jones (D-53) Erica Thomas (D-39) Walton §¨¦285 Dar'Shun Kendrick (D-93) DeKalb Karla Drenner (D-85) Kimberly Alexander (D-66) Zulma Lopez (D-86) Micah Gravley (R-67) Mesha Mainor (D-56) Stacy Evans (D-57) Renitta Shannon (D-84) Bruce Williamson (R-115) §¨¦20 Roger Bruce (D-61) Douglas Marie Metze (D-55) Bee Nyguyen (D-89) William Boddie (D-62) Fulton Park Cannon (D-58) Doreen Carter (D-92) David Dreyer (D-59) Becky Evans (D-83) §¨¦675 GreyStone Power Corporation Rockdale Carroll EMC Kim Schofield (D-60) J. -

Pfizer Inc. Regarding Congruency of Political Contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation

SANFORD J. LEWIS, ATTORNEY January 28, 2021 Via electronic mail Office of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20549 Re: Shareholder Proposal to Pfizer Inc. Regarding congruency of political contributions on Behalf of Tara Health Foundation Ladies and Gentlemen: Tara Health Foundation (the “Proponent”) is beneficial owner of common stock of Pfizer Inc. (the “Company”) and has submitted a shareholder proposal (the “Proposal”) to the Company. I have been asked by the Proponent to respond to the supplemental letter dated January 25, 2021 ("Supplemental Letter") sent to the Securities and Exchange Commission by Margaret M. Madden. A copy of this response letter is being emailed concurrently to Margaret M. Madden. The Company continues to assert that the proposal is substantially implemented. In essence, the Company’s original and supplemental letters imply that under the substantial implementation doctrine as the company understands it, shareholders are not entitled to make the request of this proposal for an annual examination of congruency, but that a simple written acknowledgment that Pfizer contributions will sometimes conflict with company values is all on this topic that investors are entitled to request through a shareholder proposal. The Supplemental letter makes much of the claim that the proposal does not seek reporting on “instances of incongruency” but rather on how Pfizer’s political and electioneering expenditures aligned during the preceding year against publicly stated company values and policies.” While the company has provided a blanket disclaimer of why its contributions may sometimes be incongruent, the proposal calls for an annual assessment of congruency. -

Coverdell Legislative Office Building

Coverdell Legislative Office Building ROOM STAFF REPRESENTATIVES PHONE 401 Chelsee Nabritt A Bill Hitchens ** E Wes Cantrell 404-656-0152 B Dave Belton F Michael Caldwell C Micah Gravley G Scot Turner D Emory Dunahoo H Barry Fleming 402 REAPPORTIONMENT Debra Miller Johnnie Caldwell** 404-656-5087 404 Cheryl Jackson A Calvin Smyre E J. Collins 404-656-0109 B Miriam Paris F Don Hogan C William Boddie G Jonathan Wallace D Deborah Silcox 405 COPY CENTER Shirley Nixon 404-463-5081 (Office) 404-656-0250 (Fax) 407 LEGISLATIVE & CONGRESSIONAL REAPPORTIONMENT (JOINT OFFICE) 404-656-5063 Gina Wright, Executive Director Tonya Cooper, Administrative Assistant 408 Wanda Scull A Trey Kelley C Heath Clark 404-657-1803 B Jesse Petrea D Mike Glanton 409 Josephine Lamar A Debbie Buckner E Dar'shun Kendrick 404-656-0116 B Darrel Ealum F Teri Anulewicz C Rhonda Burnough G David Wilkerson D Brian Prince 411 Audrea Carson A Billy Mitchell E Debra Bazemore 404-656-0126 B Dexter Sharper F HBRO ANALYST C HBRO ANALYST G Pam Stephenson D Sheila Jones H Winfred Dukes 412 HOUSE BUDGET & RESEARCH 404-656-5050 Martha Wigton- Director Alicia Hautala- Administrative Assistant 501 Kayla Bancroft A Jodi Lott E Shaw Blackmon 404.656.0177 B David Stover F Susan Holmes C Tom Kirby G Jeff Jones D Jason Spencer H Paulette Rakestraw 504 LaTricia Howard A Buzz Brockway E John Pezold 404-656-0188 B Kevin Cooke F Matt Dubnik C Clay Pirkle G D Matt Gurtler 12-20-17/Lmj Coverdell Legislative Office Building 507 Tammy Warren A Karen Bennett E Scott Hilton 404-656-0202 B Coach Williams -

Members of the General Assembly of Georgia

MEMBERS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF GEORGIA SENATE AND HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FIRST SESSION OF 2009 - 2010 TERM Copies may be obtained from THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE SENATE and THE CLERK’s OFFICE State Capitol Atlanta 30334 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Senate Leadership .......................................................... 2 Senatorial District by County ............................................ 3 State Senators Alphabetically Arranged ............................. 5 State Senators ................................................................ 7 Senate Standing Committees ......................................... 26 Legislative Offices - Senate ............................................ 37 House of Representatives Leadership .............................. 39 House of Representatives Districts by County ................... 40 Georgia House of Representative Alphabetically.............. 42 State Representatives .................................................... 47 Committees - House of Representatives ........................ 107 Congressional Districts ................................................ 131 Legislative Offices - House of Representatives ............... 144 Occupations - House and Senate ................................ 145 General Assembly Website www.legis.ga.gov Secretary of the Senate ............................... 404.656.5040 Clerk of the House ..................................... 404.656.5015 SENATE CASEY CAGLE President TOMMIE WILLIAMS President Pro Tempore BOB EWING Secretary of the Senate CHIP -

GARPAC Has Provided Financial Support to the Following State Candidates: STATEWIDE Governor Brian Kemp (R)* Lt

GARPAC has provided financial support to the following state candidates: STATEWIDE Governor Brian Kemp (R)* Lt. Governor Geoff Duncan (R)* Attorney General Chris Carr (R) Secretary of State John Barrow (D)* Commissioner of Agriculture Gary Black (R) Public Service Commission Chuck Eaton (R) (District 3 – Metro Atlanta) Public Service Commission Tricia Pridemore (R)* (District 5 – Western) SENATE 1 Ben Watson (R) 21 Brandon Beach (R) 40 Fran Millar (R) 2 Lester G. Jackson (D) 22 Harold V. Jones II (D) 41 Steve Henson (D) 3 William T. Ligon Jr. (R) 23 Jesse Stone (R) 42 Elena Parent (D) 4 Jack Hill (R) 24 Lee Anderson (R) 43 Tonya Anderson (D) 6 Leah Aldridge (R)* 25 Burt Jones (R) 44 Gail Davenport (D) 7 Tyler Harper (R) 26 David Lucas (D) 45 Renee Unterman (R) 8 Ellis Black (R) 27 Greg Dolezal (R)* 46 Bill Cowsert (R) 9 P.K. Martin (R) 28 Matt Brass (R) 47 Frank Ginn (R) 10 Emanuel Jones (D) 29 Randy Robertson (R)* 48 Matt Reeves (R)* 11 Dean Burke (R) 30 Mike Dugan (R) 49 Butch Miller (R) 12 Freddie Sims (D) 31 Bill Heath (R) 50 John Wilkinson (R) 13 Greg Kirk (R) 32 Kay Kirkpatrick (R) 51 Steve Gooch (R) 14 Bruce Thompson (R) 33 Michael “Doc” Rhett (D) 52 Chuck Hufstetler (R) 15 Ed Harbison (D) 34 Valencia Seay (D) 53 Jeff Mullis (R) 16 M.H. ‘Marty’ Harbin (R) 35 Donzella James (D) 54 Chuck Payne (R) 17 Brian Strickland (R) 36 Nan Orrock (D) 55 Gloria Butler (D) 18 John Kennedy (R) 37 Lindsey Tippins (R) 56 John Albers (R) 19 Blake Tillery (R) 38 Horacena Tate (D) 20 Larry Walker III (R) 39 Nikema Williams (D) HOUSE 5 John Meadows (R) 66 Kimberly Alexander (D) 123 Mark Newton (R) 6 Jason Ridley (R) 67 Micah Gravley (R) 127 Brian Prince (D) 7 David Ralston (R) 68 J. -

GARPAC Has Supported the Following Candidates for the 6/9/20 Primary Election: STATE SENATE 1 Ben Watson (R) 19 Blake Tillery (R) 40 Sally Harrell (D) 2 Lester G

GARPAC has supported the following candidates for the 6/9/20 Primary Election: STATE SENATE 1 Ben Watson (R) 19 Blake Tillery (R) 40 Sally Harrell (D) 2 Lester G. Jackson (D) 20 Larry Walker III (R) 42 Elena Parent (D) 3 Sheila McNeill (R)* 23 Max Burns (R)* 43 Tonya Anderson (D) 4 Billy Hickman (R)* 24 Lee Anderson (R) 44 Gail Davenport (D) 6 Jen Jordan (D) 25 Burt Jones (R) 45 Sammy Baker (R)* 7 Tyler Harper (R) 26 David Lucas (D) 46 Bill Cowsert (R) 10 Emanuel Jones (D) 27 Greg Dolezal (R) 47 Frank Ginn (R) 12 Freddie Sims (D) 28 Matt Brass (R) 49 Butch Miller (R) 13 Carden Summers (R) 30 Mike Dugan (R) 50 Andy Garrison (R)* 14 Bruce Thompson (R) 31 Jason Anavitarte (R)* 51 Steve Gooch (R) 15 Ed Harbison (D) 33 Michael “Doc” Rhett (D) 53 Jeff Mullis (R) 16 Marty Harbin (R) 34 Valencia Seay (D) 54 Chuck Payne (R) 17 Brian Strickland (R) 36 Nan Orrock (D) 55 Gloria Butler (D) 18 John Kennedy (R) 39 Nikema Williams (D) 56 John Albers (R) STATE HOUSE 4 Kasey Carpenter (R) 68 J. Collins (R) 139 Patty Bentley (D) 6 Jason Ridley (R) 69 Randy Nix (R) 140 Robert Dickey (R) 7 David Ralston (R) 70 Lynn Smith (R) 141 Dale Washburn (R) 8 Stan Gunter (R)* 72 Josh Bonner (R) 142 Miriam Paris (D) 9 Will Wade (R)* 78 Demetrius Douglas (D) 143 James Beverly (D ) 10 Terry Rogers (R) 81 Scott Holcomb (D) 144 Danny Mathis (R) 11 Rick Jasperse (R) 82 Mary Margaret Oliver (D) 145 Rick Williams (R) 13 Katie Dempsey (R) 85 Karla Drenner (D) 147 Heath Clark (R) 15 Matthew Gambill (R) 93 Dar’Shun Kendrick (D) 148 Noel Williams, Jr. -

J{Ouse Of1{Eyresentatives STACEY Y

J{ouse of1{eyresentatives STACEY Y. ABRAMS STANDING MINORITY LEADER COMMITIEES: REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 84 COVERDELL LEGISLATIVE OFFICE BUILDING, ROOM 408 APPROPRIATIONS POST OFFICE BOX 5750 ATLANTA, GEORGIA 30334 ETHICS ATLANTA, GEORGIA 31107 (404) 656-5058 JUDICIARY NON-CIVIL (404) 378·9434 (H) (404) 656-0114 (FAX) RULES E-MAIL: [email protected] WAYS AND MEANS April 20, 2011 Chairman Julius Genachowski Federal Communications Commission 445 12th Street, SW Washington, DC 20554 Re: Federal-State Joint Board on Universal Service Lifeline and Link Up ee Docket No. 96-45; we Docket 03-109; we Docket 11-42 Dear Chairman Genachowski: I write today to commend the efforts of the Federal-State Joint Board on Universal Service and Lifeline and Link Up. We believe the Lifeline program provides an invaluable service to low-income constituents in our districts and across the country. We are pleased the Board has decided to look for ways to minimize fraud, "waste and abuse in the program so that deserving and qualified families will still have access to this important program. As our nation struggles to overcome unemployment and other economic challenges, the Lifeline program is more invaluable than ever. Reports both academic and anecdotal have shown that access to phone service leads to greater chances ofemployment. Residents in our districts and nationwide, should be able to access these services in the case ofan emergency. We wholeheartedly agree with the Board's recommendations that the Commission put together a plan for uniformity on areas that would apply to all Eligible Telecommunications Carriers (ETCs) that would help eliminate waste and abuse in this program.