The Drama of Henry David Hwang

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fluidity of Religious Identity in David Henry Hwang's

International Journal of Technical Research and Applications e-ISSN: 2320-8163, www.ijtra.com Volume 5, Issue 4, (July-August) 2017), PP. 36-42 FLUIDITY OF RELIGIOUS IDENTITY IN DAVID HENRY HWANG'S GOLDEN CHILD Rajiha Kamel Muthana (Ph.D) University of Baghdad/ College of Arts/ Department of English Language [email protected] Abstract— Religion plays a significant role in the lives of Both internal and external forces are at play in Hwang's human beings, yet, religious fluidity has its own consequences. Golden Child which depicts this change in religious identity, This paper aims at investigating the impact of religious fluidity as the protagonist Tieng-Bin converts from Confucianism to on the identity of an early twentieth-century Chinese family. Christianity. This change is triggered by Tieng-Bin's Golden Child illustrates how a devoted Confucian Chinese dissatisfaction in his religious beliefs and practices which is struggles to leave parts of his culture behind by converting to considered one of the strongest internal forces. Tieng-Bin's Christianity. Tieng-Bin's conversion brings good and bad consequences to his household. The story ends with the death of travel to the Philippines, his staying there for three years, the Tieng-Bin's two wives , on the one hand, and with rebirth of influence of the Western people he has met there, as well as Tieng-Bin's daughter, Ahn, on the other hand. the influence of Reverend Baines, the missionary, who pays many visits to Tieng-Bin's household are considered external Keywords— Religious Identity, Foot Binding, Christianity, forces. Baines' lectures are attended by Tieng-Bin's second Confucianism, Tieng-Bin. -

Full Interview David Henry Hwang & Mae Ngai

An Interview with Mae Ngai & David Henry Hwang Professors Mae Ngai and David Henry Hwang spoke with us about the impact of COVID-19 on Asian-American communities. We discussed historical forces that have shaped the "model minority" and "perpetual foreigner" stereotypes; the need for bystander training and intersectional allyship; whether art can catalyze social change; and more. Interviews were conducted separately and over the phone. This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. By: Meghan Gilligan Racism against Asian Americans is not new. How would you contextualize the violence we’ ve witnessed in the past year within the larger history of anti-Asian racism in the U.S.? David Henry Hwang: I think Asians in this country have always been saddled with a perpetual foreigner stereotype. It doesn’t matter how many generations your forebears may have been here, you still get asked: “Where are you really from?” That is a microaggression, but as a result, the way that we are accepted or not accepted here is always a function of America’s relationship to Asia. In periods when there is hostility between the U.S. and Asia, Asian-Americans get caught in the crossfire. That includes World War II and the incarceration of Japanese Americans. It includes the murder of Vincent Chin in the 1980s, when there was tension between the U.S.and Japan, and unemployed auto workers mistook him for Japanese and killed him because they’d lost their jobs. It includes the racial profiling and hate attacks against South-Asian Muslims after 9/11. -

9 Short Plays from the Longest Year of Our Lives

LONG STORY SHORT 9 SHORT PLAYS FROM THE LONGEST YEAR OF OUR LIVES Sponsored by Linda Archer The Law Office of Steven Edward Buckingham Bob & Bev Howard Meghan Riordan & Chris Prince Debra & Tom Strange A Friend of The Warehouse Theatre THE WAREHOUSE THEATRE RECEIVES GENEROUS SUPPORT FROM THE JEAN T. AND HEYWARD G. PELHAM FOUNDATION AND THE HARRIET WYCHE ENDOWMENT BREAK Featuring MACHETE ORDER A LEG! by Marco Ramirez the 1 Sending our well wishes to by Cammi Stilwell Warehouse Theatre for a THIS IS DEREK by Paul Grellong spectacular show run. GERMS by Dorothy Fortenberry THE DESERT by Janine Salinas Schoenberg WAS HERE by Donald Jolly THE RELIEF OF TRUTH by Avery Sharpe SHOOTS fuelforbrands.com by Kristoffer Diaz HOPE by Bekah Brunstetter THE WAREHOUSE THEATRE PRESENTS LONG STORY SHORT BREAK Featuring MACHETE ORDER A LEG! by Marco Ramirez the 1 Sending our well wishes to by Cammi Stilwell Warehouse Theatre for a THIS IS DEREK by Paul Grellong spectacular show run. GERMS by Dorothy Fortenberry THE DESERT by Janine Salinas Schoenberg WAS HERE by Donald Jolly THE RELIEF OF TRUTH by Avery Sharpe SHOOTS fuelforbrands.com by Kristoffer Diaz HOPE by Bekah Brunstetter THE VIDEOTAPING OR MAKING OF ELECTRONIC OR OTHER AUDIO AND/OR VISUAL RECORDINGS OF THIS PRO- DUCTION OR DISTRIBUTING RECORDINGS OF ANY MEDIUM, INCLUDING THE INTERNET, IS STRICTLY PROHIB- ITED, A VIOLATION OF THE AUTHOR’S RIGHTS AND ACTIONABLE UNDER UNITED STATES COPYRIGHT LAW. FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR There have been many adjustments we’ve had to make at The Warehouse over the past 15 months. -

Curran San Francisco Announces Cast for the Bay Area Premiere of Soft Power a Play with a Musical by David Henry Hwang and Jeanine Tesori

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Curran Press Contact: Julie Richter, Charles Zukow Associates [email protected] | 415.296.0677 CURRAN SAN FRANCISCO ANNOUNCES CAST FOR THE BAY AREA PREMIERE OF SOFT POWER A PLAY WITH A MUSICAL BY DAVID HENRY HWANG AND JEANINE TESORI JUNE 20 – JULY 10, 2018 SAN FRANCISCO (March 6, 2018) – Today, Curran announced the cast of SOFT POWER, a play with a musical by David Henry Hwang (play and lyrics) and Jeanine Tesori (music and additional lyrics). SOFT POWER will make its Bay Area premiere at San Francisco’s Curran theater (445 Geary Street), June 20 – July 8, 2018. Produced by Center Theatre Group, SOFT POWER comes to Curran after its world premiere at the Ahmanson Theatre in Los Angeles from May 3 through June 10, 2018. Tickets for SOFT POWER are currently only available to #CURRAN2018 subscribers. Single tickets will be announced at a later date. With SOFT POWER, a contemporary comedy explodes into a musical fantasia in the first collaboration between two of America’s great theatre artists: Tony Award winners David Henry Hwang (M. Butterfly, Flower Drum Song) and Jeanine Tesori (Fun Home). Directed by Leigh Silverman (Violet) and choreographed by Sam Pinkleton (Natasha, Pierre, & the Great Comet of 1812), SOFT POWER rewinds our recent political history and plays it back, a century later, through the Chinese lens of a future, beloved East-meets-West musical. In the musical, a Chinese executive who is visiting America finds himself falling in love with a good-hearted U.S. leader as the power balance between their two countries shifts following the 2016 election. -

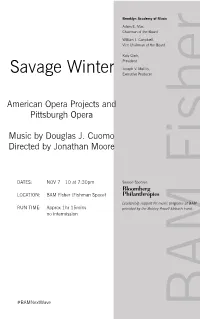

Savage Winter #Bamnextwave No Intermission LOCATION: RUN TIME: DATES: Pittsburgh Opera Approx 1Hr15mins BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) NOV 7—10At7:30Pm

Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Savage Winter Executive Producer American Opera Projects and Pittsburgh Opera Music by Douglas J. Cuomo Directed by Jonathan Moore DATES: NOV 7—10 at 7:30pm Season Sponsor: LOCATION: BAM Fisher (Fishman Space) Leadership support for music programs at BAM RUN TIME: Approx 1hr 15mins provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund. no intermission #BAMNextWave BAM Fisher Savage Winter Written and Composed by Music Director This project is supported in part by an Douglas J. Cuomo Alan Johnson award from the National Endowment for the Arts, and funding from The Andrew Text based on the poem Winterreise by Production Manager W. Mellon Foundation. Significant project Wilhelm Müller Robert Signom III support was provided by the following: Ms. Michele Fabrizi, Dr. Freddie and Directed by Production Coordinator Hilda Fu, The James E. and Sharon C. Jonathan Moore Scott H. Schneider Rohr Foundation, Steve & Gail Mosites, David & Gabriela Porges, Fund for New Performers Technical Director and Innovative Programming and The Protagonist: Tony Boutté (tenor) Sean E. West Productions, Dr. Lisa Cibik and Bernie Guitar/Electronics: Douglas J. Cuomo Kobosky, Michele & Pat Atkins, James Conductor/Piano: Alan Johnson Stage Manager & Judith Matheny, Diana Reid & Marc Trumpet: Sir Frank London Melissa Robilotta Chazaud, Francois Bitz, Mr. & Mrs. John E. Traina, Mr. & Mrs. Demetrios Patrinos, Scenery and properties design Assistant Director Heinz Endowments, R.K. Mellon Brandon McNeel Liz Power Foundation, Mr. & Mrs. William F. Benter, Amy & David Michaliszyn, The Estate of Video design Assistant Stage Manager Jane E. -

Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity Through DNA: the DNA Trail

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 23 (2012) Finding, Reclaiming, and Reinventing Identity through DNA: The DNA Trail Yuko KURAHASHI* The DNA Trail: A Genealogy of Short Plays about Ancestry, Identity, and Utter Confusion (2011) is a collection of seven fifteen-to-twenty minute plays by veteran Asian American playwrights whose plays have been staged nationally and internationally since the 1980s. The plays include Philip Kan Gotanda’s “Child Is Father to Man,” Velina Hasu Houston’s “Mother Road,” David Henry Hwang’s “A Very DNA Reunion,” Elizabeth Wong’s “Finding Your Inner Zulu,” Shishir Kurup’s “Bolt from the Blue,” Lina Patel’s “That Could Be You,” and Jamil Khoury’s “WASP: White Arab Slovak Pole.” Conceived by Jamil Khoury and commissioned and developed by Silk Road Theatre Project in Chicago in association with the Goodman Theatre, a full production of the seven plays was mounted at Silk Road Theatre Project in March and April 2010.1 On January 22, 2011, Visions and Voices: The USC Arts and Humanities Initiative presented a staged reading at the Uni- versity of Southern California, Los Angeles, using revised scripts. The staged reading was directed by Goodman Theatre associate producer Steve Scott, who had also directed the original production.2 San Francisco–based playwright Gotanda has written plays that reflect his yearning to learn the stories of his Japanese American parents, and their friends and relatives. His plays include A Song for a Nisei Fisherman (1980), The Wash (1985), Ballad of Yachiyo (1996), and Sisters *Associate Professor, Kent State University 285 286 YUKO KURAHASHI Matsumoto (1997). -

M. Butterfly As Total Theatre

M. Butterfly as Total Theatre Mª Isabel Seguro Gómez Universitat de Barcelona [email protected] Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly from the perspective of a semiotics on theatre, following the work of Elaine Aston and George Savona (1991). The reason for such an approach is that Hwang’s play has mostly been analysed as a critique of the interconnections between imperialism and sexism, neglecting its theatricality. My argument is that the theatrical techniques used by the playwright are also a fundamental aspect to be considered in the deconstruction of the Orient and the Other. In a 1988 interview, David Henry Hwang expressed what could be considered as his manifest on theatre whilst M. Butterfly was still being performed with great commercial success on Broadway:1 I am generally interested in ways to create total theatre, theatre which utilizes whatever the medium has to offer to create an effect—just to keep an audience interested—whether there’s dance or music or opera or comedy. All these things are very theatrical, even makeup changes and costumes—possibly because I grew up in a generation which isn’t that acquainted with theatre. For theatre to hold my interest, it needs to pull out all its stops and take advantage of everything it has— what it can do better than film and television. So it’s very important for me to exploit those elements.… (1989a: 152-53) From this perspective, I would like to analyse the theatricality of M. Butterfly as an aspect of the play to which, traditionally, not much attention has been paid to as to its content and plot. -

Prayers and Offices of Devotion, for Families and for Particular Persons

EH(^ 4 — — PR A YEES AND OFFICES OF DEVOTION, FOB FAMILIES PARTICULAR PERSONS UPON MOST OCCASIONS. BY BENJAMIN JENKS, LATB RECTOR OF HAELEY, IN SHROPSHIRE, AND CHAPLAIN TO THJS RIGHT HONORABLE THE EAKL OF BRADFORD. Men ought always to pray and not to faint. Luke xviii. 1. Continue in prayer, and watch in the same with thanksgiving. Ool. iv.2 ALTERED AND IMPROVED BY THE REV. CHARLES SIMEON, FELLOW OF king's COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. THE ELEVENTH THOUSAND. STANFORD AND SWORDS, 137, BROADWAY. 1850. : THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY 409602 ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDEN POUNDAT«ON8. 1908 Ekteeed according to Act of Congress, in the year 1832, by SWORDS, STANFORD & CO. in the Clerk's Office of the District Court, for the Southern District of New-York. Hohart Press JOHN K. M'GOWN, PniNTEH, CVI, FULTON-STREET. TO THE READER. The subscribers have thought, that it would gi'eatly tend to the promotion and interest of true piety, to have a republication, in this country, of the improved edition of the Prayers and Offices of Devotion of the late pious and reverend Benjamin Jenks. Under this impression, they have caused a set of stereotype plates of that work to be cast; but, in doing this, they have found it necessary to alter several phrases that were antiquated and obsolete, and to expunge two or three of the prayers, and in others, some sentences that were altogether local, and not adapted for our country. The copy they have made use of was the thirty-third, and last London edition, published under the superintendence of the learned and reverend Charles Simeon, M. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER “Falsettos” TCA Biographies ANDREW C. WILK Andrew C. Wilk Is a Multiple Emmy Award-Winning Producer

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER “Falsettos” TCA Biographies ANDREW C. WILK Andrew C. Wilk is a multiple Emmy Award-winning producer and director whose career has encompassed leading roles in many areas of commercial and educational content. Since his arrival at Lincoln Center in 2011, he has served as executive producer of Live From Lincoln Center episodes ranging from classical music to dance to theatre. Prior to his work at Lincoln Center, Wilk served as Chief Creative Officer at Sony Music Entertainment, where he oversaw all visual content for Sony’s label groups and spearheaded Sony’s digital expansion. He also served as Founding Programmer and Executive Vice President of Programming and Production for the National Geographic Channel, where he launched the channel and developed its initial programming and scheduled and commissioned new programs, including specials with PBS and NBC. Wilk has won five Emmy Awards and received 15 nominations. Over the course of his career, he has produced or directed more than 1,000 television shows, ranging from children’s programming to news to commercial entertainment, in addition to continuing his work as a conductor of live music concerts. JAMES LAPINE James Lapine collaborated with Stephen Sondheim as author and director for Sunday in the Park With George; Into the Woods; Passion; and the multi-media revue Sondheim on Sondheim. He also directed Merrily We Roll Along as part of Encores at New York City Center. With William Finn, he has collaborated on March of the Falsettos and Falsettoland, later presented on Broadway as Falsettos and recently revived in 2016; A New Brain; Muscle; and Little Miss Sunshine. -

“Orient” in David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly

THE REPRESENTATION OF THE “ORIENT” IN DAVID HENRY HWANG’S M. BUTTERFLY SHUCHI GUPTA Ph. D. Research Scholar Department of English and Modern European Languages University of Lucknow (UP) INDIA. The aim of this paper is to critically analyze the representation of an “orient” in David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly. In this drama, gender, racial and imperial discourses intersect and Hwang has been successful in deconstructing these traditional discourses and exposing the fictitiousness of stereotypical image of an orient harboured by the ‘West’. The drama employs postmodernist aesthetics and brilliant theatrical techniques to foreground the deconstruction of traditional representations that follow. Traditionally ‘East’ has always been misrepresented by the west. This misrepresentation is the result of an essentialist view based upon gender and racial discourses. The play also shows how national entity narratives are internalized and adapted in the construction of the individual subject. Key Words: Orientalism, Race, Gender, Identity. INTRODUCTION David Henry Hwang is an American playwright and screen writer. Born on 11 August, 1957 to Chinese American parents, his early plays concerned the role of the Chinese- American and Asian- American in the modern day world. The identity issues that haunt the immigrants and their children have been explored by Hwang in a series of plays. These identity issues arise due to the conflict between ethnic value system which they are obliged to preserve as their authentic identity and the new value system which they are obliged to harmonize with in order to start a new life. The conflict becomes more complicated when it concerns the people of Asian descent because it is placed at the intersection of racism and imperialism. -

Fantasy, Narcissism and David Henry Hwang's M. Butterfly

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 554 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Humanities and Social Science Research (ICHSSR 2021) Fantasy, Narcissism and David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly Shu-Yuan Chang1 1School of Foreign Languages, Zhaoqing University, Zhaoqing 526061, China *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT David Henry Hwang’s M. Butterfly deconstructs Giacomo Puccini’s Madame Butterfly by entwining a fact happened in 1986 — a French diplomat Bernard Bouriscot who has a multi-year affair with a Chinese man disguised as a woman. Hwang displays how cultural imperialism and the stereotype of the Asian persona through the protagonist Gallimard who unconsciously perceives superiority of Western power over Eastern weakness, and the Western colonial male over the Asian female. Gallimard falls in love with the Chinese actress Song Liling to whom he projects his fantasy of a “perfect woman” without noticing the fact Song Liling is a man and a spy. His relationship with Song can be interpreted by concept of the Other in Western concept. This study discusses how Gallimard in M. Butterfly reflects the “Narcissus myth”, how “Othered self” and “selfed Other” work upon him as well as how Song, as a man, satisfies his Western superiority to the power of control and fantasy to an Oriental woman. Keywords: Cultural imperialism, Stereotype of the Asian persona, Superiority, Fantasy, Narcissus myth, The Other concluded that the diplomat [Bouriscot] must have fallen 1. INTRODUCTION in love not with a person but with a fantasy stereotype” When it comes to the issue of the East and the West, [1]. -

Doc ^ the Flower Drum Song ^ Read

GHCQ3WHX1N ^ The Flower Drum Song \\ Book Th e Flower Drum Song By C Y Lee Penguin Books, United States, 2002. Paperback. Book Condition: New. Reprint. 198 x 128 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. Originally published in 1957, The Flower Drum Song was a groundbreaking work of popular literature. An immediate bestseller, it inspired the classic Rodgers and Hammerstein musical. This charming, bittersweet tale of romance and the powerful bonds of family tells the story of Wang Ta, who wants what every young American man wants: a great career and a woman to love. Living in San Francisco s Chinatown-with his widowed father, Old Master Wang, who misses the old way of life in China, and his younger brother, who just wants to be a normal American teenager-Wang Ta becomes involved with a series of women as he searches for love and the American dream. Comic, poignant, and sexy, The Flower Drum Song is an astute portrayal of immigrants struggling with assimilation. This edition features a new introduction by David Henry Hwang. READ ONLINE [ 2.53 MB ] Reviews A top quality ebook as well as the typeface used was interesting to see. It usually fails to charge an excessive amount of. Once you begin to read the book, it is extremely difficult to leave it before concluding. -- Dr. Isabell Wiza DDS This written book is excellent. It really is rally fascinating throgh studying period. You are going to like the way the writer write this publication. -- Hadley Ullrich 6VGOW9HYFX ^ The Flower Drum Song # Book Related eBooks Becoming Barenaked: Leaving a Six Figure Career, Selling All of Our Crap, Pulling the Kids Out of School, and Buying an RV We Hit the Road in Search Our Own American Dream.