S.Y.B.A. English Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Cinema

History of Cinema Series 1 Hollywood and the Production Code Selected files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration collection. Filmed from the holdings of the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Primary Source Media History of Cinema Series 1 Hollywood and the Production Code Selected files from the Motion Picture Association of America Production Code Administration collection. Filmed from the holdings of the Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Primary Source Media 12 Lunar Drive, Woodbridge, CT 06525 Tel: (800) 444 0799 and (203) 397 2600 Fax: (203) 397 3893 P.O. Box 45, Reading, England Tel: (+44) 1734 583247 Fax: (+44) 1734 394334 ISBN: 1-57803-354-3 All rights reserved, including those to reproduce this book or any parts thereof in any form Printed and bound in the United States of America © 2006 Thomson Gale A microfilm product from Primary Source Media COPYRIGHT STATEMENT The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials including foreign works under certain conditions. In addition, the United States extends protection to foreign works by means of various international conventions, bilateral agreements, and proclamations. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement. -

Jesuit Hollywood

JESUIT HOLLYWOOD Shaun Willcock BIBLE BASED MINISTRIES First published in 2015 for Bible Based Ministries by New Voices Publishing Cape Town, South Africa www.newvoices.co.za Bible Based Ministries www.biblebasedministries.co.uk [email protected] Bible Based Ministries’ worldwide contact: Contending for the Faith Ministries 695 Kentons Run Ave Henderson, NV 89052 United States of America [email protected] IMPORTANT NOTICE: The author has no objection whatsoever to anyone reproducing this book in printed form for free distribution, provided it is reproduced in full, including the cover, without being altered or edited in any way. His desire is for this book to be as widely distributed as possible. However, anyone wanting to print the book for sale, must obtain permission from the author. ABOUT THE SOURCES REFERRED TO IN THIS BOOK: In writing this book, factual information was compiled from a number of sources, which are referred to in this book for documentation purposes. However, reference to a particular source does not by any means necessarily imply agreement with the doctrinal position of the author, nor with every statement in the work referred to. ISBN-PRINT: 987-0-620-66718-0 ISBN-EBOOK: 978-0-620-66719-7 2 - CONTENTS Introduction 5 Chapter 1: The Jesuit Use of the Dramatic Arts 8 Chapter 2: The Jews Create Hollywood 19 Chapter 3: Protestants, Roman Catholics and Film Censorship in the Early Years 35 Chapter 4: Jesuit Regulation of the Movie Industry: The Production Code 52 Chapter 5: Joseph I. Breen and The Code 72 -

Crime Thriller Cluster 1

Crime Thriller Cluster 1 movie cluster 1 1971 Chhoti Bahu 1 2 1971 Patanga 1 3 1971 Pyar Ki Kahani 1 4 1972 Amar Prem 1 5 1972 Ek Bechara 1 6 1974 Chowkidar 1 7 1982 Anokha Bandhan 1 8 1982 Namak Halaal 1 9 1984 Utsav 1 10 1985 Mera Saathi 1 11 1986 Swati 1 12 1990 Swarg 1 13 1992 Mere Sajana Saath Nibhana 1 14 1996 Majhdhaar 1 15 1999 Pyaar Koi Khel Nahin 1 16 2006 Neenello Naanalle 1 17 2009 Parayan Marannathu 1 18 2011 Ven Shankhu Pol 1 19 1958 Bommai Kalyanam 1 20 2007 Manase Mounama 1 21 2011 Seedan 1 22 2011 Aayiram Vilakku 1 23 2012 Sundarapandian 1 24 1949 Jeevitham 1 25 1952 Prema 1 26 1954 Aggi Ramudu 1 27 1954 Iddaru Pellalu 1 28 1954 Parivartana 1 29 1955 Ardhangi 1 30 1955 Cherapakura Chedevu 1 31 1955 Rojulu Marayi 1 32 1955 Santosham 1 33 1956 Bhale Ramudu 1 34 1956 Charana Daasi 1 35 1956 Chintamani 1 36 1957 Aalu Magalu 1 37 1957 Thodi Kodallu 1 38 1958 Raja Nandini 1 39 1959 Illarikam 1 40 1959 Mangalya Balam 1 41 1960 Annapurna 1 42 1960 Nammina Bantu 1 43 1960 Shanthi Nivasam 1 44 1961 Bharya Bhartalu 1 45 1961 Iddaru Mitrulu 1 46 1961 Taxi Ramudu 1 47 1962 Aradhana 1 48 1962 Gaali Medalu 1 49 1962 Gundamma Katha 1 50 1962 Kula Gotralu 1 51 1962 Rakta Sambandham 1 52 1962 Siri Sampadalu 1 53 1962 Tiger Ramudu 1 54 1963 Constable Koothuru 1 55 1963 Manchi Chedu 1 56 1963 Pempudu Koothuru 1 57 1963 Punarjanma 1 58 1964 Devatha 1 59 1964 Mauali Krishna 1 60 1964 Pooja Phalam 1 61 1965 Aatma Gowravam 1 62 1965 Bangaru Panjaram 1 63 1965 Gudi Gantalu 1 64 1965 Manushulu Mamathalu 1 65 1965 Tene Manasulu 1 66 1965 Uyyala -

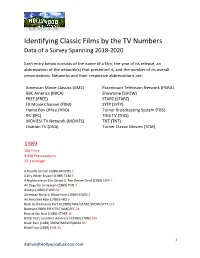

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020

Identifying Classic Films by the TV Numbers Data of a Survey Spanning 2018-2020 Each entry below consists of the name of a film, the year of its release, an abbreviation of the network(s) that presented it, and the number of its overall presentations. Networks and their respective abbreviations are: American Movie Classics (AMC) Paramount Television Network (PARA) BBC America (BBCA) Showtime (SHOW) FREE (FREE) STARZ (STARZ) FX Movie Channel (FXM) SYFY (SYFY) Home Box Office (HBO) Turner Broadcasting System (TBS) IFC (IFC) THIS TV (THIS) MOVIES! TV Network (MOVIES) TNT (TNT) Ovation TV (OVA) Turner Classic Movies (TCM) 1989 150 Films 4,958 Presentations 33,1 Average A Deadly Silence (1989) MOVIES 1 A Dry White Season (1989) TCM 4 A Nightmare on Elm Street 5: The Dream Child (1989) SYFY 7 All Dogs Go to Heaven (1989) THIS 7 Always (1989) STARZ 69 American Ninja 3: Blood Hunt (1989) STARZ 2 An Innocent Man (1989) HBO 5 Back to the Future Part II (1989) MAX/STARZ/SHOW/SYFY 272 Batman (1989) SYFY/TNT/AMC/IFC 24 Best of the Best (1989) STARZ 16 Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989) STARZ 140 Black Rain (1989) SHOW/MOVIES/MAX 85 Blind Fury (1989) THIS 15 1 [email protected] Born on the Fourth of July (1989) MAX/BBCA/OVA/STARZ/HBO 201 Breaking In (1989) THIS 5 Brewster’s Millions (1989) STARZ 2 Bridge to Silence (1989) THIS 9 Cabin Fever (1989) MAX 2 Casualties of War (1989) SHOW 3 Chances Are (1989) MOVIES 9 Chattahoochi (1989) THIS 9 Cheetah (1989) TCM 1 Cinema Paradise (1989) MAX 3 Coal Miner’s Daughter (1989) STARZ 1 Collision -

Beastly Journeys

beastly journeys LIVERPOOL ENGLISH TEXTS AND STUDIES 63 BEASTLY JOURNEYS Travel and Transformation at the fin de siècle TIM YOUNGS LIVERPOOL UNIVERSITY PRESS First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Tim Youngs The right of Tim Youngs to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication data A British Library CIP record is available ISBN 978-1-84631-958-7 cased Typeset by XL Publishing Services Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY For John and Pauline Lucas Contents Acknowledgements ix Introduction: The Unchaining of the Beast 1 1 City Creatures 39 2 The Bat and the Beetle 74 3 Morlocks, Martians, and Beast-People 107 4 ‘Beast and man so mixty’: The Fairy Tales of George MacDonald 140 5 Oscar Wilde: ‘an unclean beast’ 165 Conclusion 197 Bibliography 211 Index 220 vii Acknowledgements This book has had a long gestation. Early stages of it were supported through research leave funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Board and through my own university department’s sabbatical programme. I am grateful to both bodies. The following people have also helped through, variously, their provision of ideas, information, encour- agement, and the hosting of lectures, seminars, and conferences at which early drafts of some material were tried out: Chris Barker, Dinah Birch, Joseph Bristow, Antoinette Burton, Viv Chadder, Stephen Donovan, Justin D. -

Doctor Who Cats Cradle Witch Mark

Contents Prologue...................................................................................... .......................3 1: Arrivals ..................................................................... ................................12 2: Strange Beasts .................................................................................. .........23 3: Missing Persons .................................................................. ......................38 4: Arawn's Wheel .............................................................................. ............44 5: An Unexpected Party ............................................................. ...................57 6: A Journey in the Dark ................................................................. ..............62 7: Unwelcome Visitors ............................................. ....................................75 8: Three Is Company ................................................................................ .....79 9: Rissole Time .................................................................. ...........................87 10: Many Meetings .............................................................. ...........................91 11: Corn Circles...................................................................... .......................101 12: Fire and Water .................................................... ....................................105 13: The Land of Shadow ...................................................................... .........114 -

Rating Guide Daughter Are Held Captive for 53 Days by 354 Sept

Absolution Action A contract killer is torn Action Point 56 Comedy D.C. is the between protecting a girl from human crackpot owner of a low-rent amusement traffickers and remaining loyal to his park where the rides are designed with government agency employers. Steven minimum safety for maximum fun. When a Perrey Reeves, Kim Shaw, Gord Rand, Seagal, Vinnie Jones, Byron Mann, Josh corporate mega-park opens nearby, D.C. A Kristin Booth. (TV14, 2:00) ’20 LMN 109 Barnett. (1:45) ’15 SONY 386 Sept. 5 and his loony crew of misfits must pull 6:15p; 6 9:45a; 25 9:40p; 27 6:15p; 28 out all the stops to try and save the day. Abbott and Costello in Hol- Sept. 21 12p 2:15p; 30 11:20a Johnny Knoxville, Chris Pontius, Dan lywood 556 Comedy Two Abducted: The Carlina White Story A An Acceptable Loss 56 Suspense Bakkedahl, Matt Schulze. (1:25) ’18 EPIX bumbling barbers act as agents Docudrama Ann Pettway kidnaps an 380 Sept. 14 5:15a, EPIX2 381 Sept. 10 for an unknown singer and stage infant from a New York hospital and Haunted by what she knows, a former 5:15a, EPIXHIT 382 Sept. 18 8:05a a phony murder to get him a coveted raises the child as her own daughter. national security adviser risks her life to role. Bud Abbott, Lou Costello, Frances Aunjanue Ellis, Keke Palmer, Sherri expose a massive cover-up involving thou- Acts of Violence Action A man teams Rafferty, Robert Stanton. (NR, 1:24) ’45 Shepherd, Roger Cross.