Breaking Boundaries: Black Magazines Reconstructing Black Female Identity a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undermining Black Enterprise with Land Use Rules

CLOWNEY.DOC 7/10/2009 2:12 PM INVISIBLE BUSINESSMAN: UNDERMINING BLACK ENTERPRISE WITH LAND USE RULES Stephen Clowney* Rates of self-employment in African-American neighborhoods remain feeble. Although the reasons behind the failure of black busi- nesses are complex, zoning regulations play a largely unexamined role in constraining the development of African-American enterpris- es. Land use fees, municipal zoning board decisions, and the general insistence on separating residential from commercial uses all impress unique and disproportionate harms on African-American merchants, making it difficult to find affordable business space in suitable loca- tions. Moreover, current attempts to reorganize the land use system are inadequate to solve the problems facing black businesspeople. A complete rolling back of zoning laws is impractical and unnecessary, while attempts to promote street vending or home-based business run aground on the objections of local homeowners. Instead of pursuing these failed strategies, municipal governments should create programs that transfer abandoned buildings to fledgling merchants of the inner city. This new land use policy could spark a revival of urban entre- preneurship and help restore crumbling neighborhoods to their for- mer glory. Unlike other proposals to reform zoning laws, transfer- ring vacant government-owned land unites the interests of businesspeople, homeowners, and local governments. Inner-city merchants receive the space they need to foster new business ideas. Local homeowners rid themselves of the scourge of empty buildings. Finally, municipalities generate new revenue by returning unproduc- tive buildings to the tax rolls. INTRODUCTION At the start of the twenty-first century, land use reform is the most underexamined method of restoring the economic vitality of central ci- ∗ Assistant Professor of Law, University of Kentucky. -

Pamela Rose Smith

THE IMAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AS PRESENTED BY AMERICAN MASS MEDIA AND POPULAR CULTURE: INTERPRETATIONS BY URBAN AFRICAN AMERICAN ADOLESCENT FEMALES REGARDING THEIR LIFE CHANCES, LIFE CHOICES, AND SELF-ESTEEM By Pamela Rose Smith A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Sociology - Doctor of Philosophy 2014 ABSTRACT THE IMAGE OF AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN AS PRESENTED BY AMERICAN MASS MEDIA AND POPULAR CULTURE: INTERPRETATIONS BY URBAN AFRICAN AMERICAN ADOLESCENT FEMALES REGARDING THEIR LIFE CHANCES, LIFE CHOICES, AND SELF-ESTEEM By Pamela Rose Smith The aim of this study was to investigate the image of African American women in popular culture and gain an understanding of how those images are interpreted by urban African American adolescent girls (N=40) between the ages of 13-19 years old. Black magazine covers and hip-hop/rap music videos that display images of African American women were viewed by the participants. Questions were asked of the girls that explored whether popular culture media images of African American women affect the interpretation of their self-esteem, choices they make, and future chances in life. Specifically, I sought to understand: 1) Do images of African American women shown in popular culture influence the interpretation of life chances and life choices of urban African American adolescent girls, and if so, how?; and 2) Whether portrayals of African American women in popular culture influence the interpretation of the self-esteem of urban African American adolescent girls. A mixed method research process was used to gather data that represents the participants’ perspectives. -

African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(S) of Race Lisa Brock Art Institute of Chicago

Contributions in Black Studies A Journal of African and Afro-American Studies Volume 12 Ethnicity, Gender, Culture, & Cuba Article 3 (Special Section) 1994 Back to the Future: African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(s) of Race Lisa Brock Art Institute of Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs Recommended Citation Brock, Lisa (1994) "Back to the Future: African-Americans and Cuba in the Time(s) of Race," Contributions in Black Studies: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/cibs/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Afro-American Studies at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Contributions in Black Studies by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brock: Back to the Future Lisa Brock BACK TO THE FUTURE: AFRICAN AMERICANS AND CUBA IN THE TIME(S) OF RACE* UBA HAS, AT LEAST SINCE the American revolution, occupied the imagination of North Americans. For nineteenth-century capital, Cuba's close proximity, its C Black slaves, and its warm but diverse climate invited economic penetration. By 1900, capital desired in Cuba "a docile working class, a passive peasantry, a compliant bourgeoisie, and a subservient political elite.'" Not surprisingly, Cuba's African heritage stirred an opposite imagination amongBlacksto the North. The island's rebellious captives, its anti-colonial struggle, and its resistance to U.S. hegemony beckoned solidarity. Like Haiti, Ethiopia, and South Africa, Cuba occupied a special place in the hearts and minds of African-Americans. -

Diversity, Inclusion, and Impact Symposium

Diversity, Inclusion, and Impact Symposium September 17, 2020 #DCEODiversityandInclusion Thank you to our sponsors! TITLE SPONSORS: SIGNATURE SPONSORS: PRODUCTION PARTNER: Agenda 7:45 AM: Morning Meditation with Veleisa Patton Burrell from Mastermind Meditate 8 AM: Welcome Remarks by Gillea Allison and Christine Perez 8:10 AM: Opening Keynote - What Equity, Justice, and Belonging Needs from Each of Us by Lisa M. Ong 9 AM: My Reality - How Her Life Experiences Shaped Her Mission Towards Advocating for Equality by Laura Ramirez 9:30 AM: Networking Break 10 AM: My Reality - I Choose to Be Bold and Authentic Without Apology by Beverley Wright 10:30 AM: Panel - Data and Transparency: Setting Goals and Measuring Results 11:30 AM: My Reality – Plan, Prepare, Pivot: The PPP of Leadership by Darren L. James 12 PM: Lunch Breakout Session - Moving Toward Racial Equity and Racial Healing with Dallas Truth, Racial Healing and Transformation 1 PM: Panel – Getting Comfortable with Uncomfortable Conversations 1:45 PM: From Virtue Signaling to Real Change Inside/Out: A Marketing Fireside Chat with Marcus Graham Project 2:30 PM: Networking Break 3:00 PM: Panel - Shaping the Future: Calls to Action and Steps Toward Progress 3:45 PM: Closing Keynote – Finding the Opportunity in Every Challenge by John Olajide A Virtual Guide and Welcome Dear Attendees, We are thrilled to have you be a part of the second annual 2020 Diversity, Inclusion, and Impact Symposium, with the most robust speaker lineup we’ve had and several options to connect and engage, albeit virtually. We are thankful to our sponsors and attendees who help make this event possible. -

African American Newsline Distribution Points

African American Newsline Distribution Points Deliver your targeted news efficiently and effectively through NewMediaWire’s African−American Newsline. Reach 700 leading trades and journalists dealing with political, finance, education, community, lifestyle and legal issues impacting African Americans as well as The Associated Press and Online databases and websites that feature or cover African−American news and issues. Please note, NewMediaWire includes free distribution to trade publications and newsletters. Because these are unique to each industry, they are not included in the list below. To get your complete NewMediaWire distribution, please contact your NewMediaWire account representative at 310.492.4001. A.C.C. News Weekly Newspaper African American AIDS Policy &Training Newsletter African American News &Issues Newspaper African American Observer Newspaper African American Times Weekly Newspaper AIM Community News Weekly Newspaper Albany−Southwest Georgian Newspaper Alexandria News Weekly Weekly Newspaper Amen Outreach Newsletter Newsletter Annapolis Times Newspaper Arizona Informant Weekly Newspaper Around Montgomery County Newspaper Atlanta Daily World Weekly Newspaper Atlanta Journal Constitution Newspaper Atlanta News Leader Newspaper Atlanta Voice Weekly Newspaper AUC Digest Newspaper Austin Villager Newspaper Austin Weekly News Newspaper Bakersfield News Observer Weekly Newspaper Baton Rouge Weekly Press Weekly Newspaper Bay State Banner Newspaper Belgrave News Newspaper Berkeley Tri−City Post Newspaper Berkley Tri−City Post -

Jewish Merchants and Black Customers in the Age of Jim Crow

Jewish Merchants and Black Customers in the Age of Jim Crow by Clive Webb n 1920 Aaron Bronson, a Russian Jewish immigrant, moved his family to a small town in western Tennessee with the I intention of establishing a retail store. After his arrival in the United States, for a short time Bronson had worked in the employ of a Jewish merchant in Savannah. From this experience he had learned the two essential rules necessary for a Jew to operate a successful business in the American South. The first rule was that, unlike in his native homeland where Jewish stores "in observance of the Sabbath, were closed on Saturdays and open on Sundays, here it was the other way round." The second rule concerned the treatment of African Americans. According to his employer, there was sufficient suspicion of Jews among the white Protestant majority without their stirring up trouble over the race issue. No matter what personal sympathies the mer- chant might have with African Americans, good business sense dictated public acceptance of the status quo. As he curtly informed Bronson: "I'm here for a living, not a crusade." Bronson adhered strictly to these rules when he opened his own store. Although he held no prejudice towards African Americans, he refrained from any overt action that might risk retaliation from enraged whites. Instead he contented himself with small acts of kindness towards his black customers. As his daughter re- flects, "What he did was keep quiet about it and do the best he could do."1 56 SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY The story of Aaron Bronson is symptomatic of the experience of Jewish merchants operating in the small towns of the South during the Jim Crow era. -

Black Periodicals and Newspapers. a Union List of Holdings in Libraries of the University of Wisconsin and the Library of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 192 BOO IR 008 882 AUTHOR Strache, Neil EA, Comp.: And Others TITLE Black Periodicals and Newspapers. A Union List of Holdings in Libraries of the University of Wisconsin and the Library of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Second Edition, Revised. INSTITUTION Wisconsin State Historical Society, Madison. PUE CATE 79 NOTE 93p.: For related docusett, see ED 130 290. EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Black Literature: *Blacks: Indexes: *Library Collections: *Newspapers: *Periodicals: Union Catalogs' ABSTRACT This second edition of Black Periodicals and Newspapers is a guide to the holdings and locations of more than 600 periodical and newspaper titles relating to black Americans which were received before February 1979 in the libraries of the University of Wisconsin-Eadison and in the Library of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. The guide includes literary, political, and historical journals, a:. well as general newspapers and feature magazines cf the black community. A comparison is made of the number of titles representing each state in this edition and in the original guide. Wisconsin libraries whose holdings appear in the guide are listed. The union list itself is arranged alphabetically by title, and a geograpbic index to the titles (by state and principal cities' follows. A subject index is also provided. (SW' *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U S. DORAN TWINE OP REALM EDUCATION a WELPARE C:) NATIONAL INSMUTE OP EOUCAE1ON Q THIS DOCUMENT HAS RUN Rem. Duce* EXACTLY AS RECEIVED RAW THEPERSON OR °ROAN'S MIN OR MIN. -

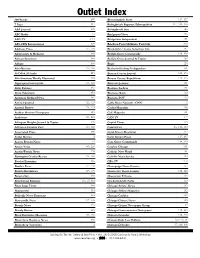

Outlet Index

Outlet Index 600 Words 207 Bloomingdale Press 117, 137 7 Days 217 Bolingbrook Reporter/Metropolitan 117, 140, 146 ABA Journal 185 Bolingbrook Sun 146 ABC Radio 31 Bridgeport News 226 ABC-TV 2, 16 Bridgeview Independent 151 ABS-CBN International 197 Brighton Park/McKinley Park Life 226 Addison Press 117, 136 Brookfield / Lyons Suburban Life 137 Adolescents & Medicine 185 Buffalo Grove Countryside 119, 128 African-Spectrum 189 Buffalo Grove Journal & Topics 128 Afrique 189 Bugle 126 Afro-Netizen 113, 189 Burbank-Stickney Independent 151 Al-Offok Al-Arabi 215 Bureau County Journal 121, 176 Alfa American Weekly Illustrated 203 Bureau County Republican 121, 176 Algonquin Countryside 118, 128 Business Journal 101 Alsip Express 151 Business Ledger 101 Alton Telegraph 153 Business Week 182 American Medical News 182 BusinessPOV 113 Antioch Journal 122, 123 Cable News Network - CNN 2 Antioch Review 118, 123 Cachet Magazine 190 Arabian Horizon Newspaper 215 Café Magazine 101 Arabstreet 113, 215 CAN TV 1, 7 Arlington Heights Journal & Topics 128 Capital Times 153 Arlington Heights Post 119, 128 Capitol Fax Sec 1:34, 109 Associated Press 108 Carol Stream Examiner 137 At the Movies 2 Carol Stream Press 117, 137 Aurora Beacon News 91 Cary-Grove Countryside 118, 129 Austin Voice 189, 224 Catalyst Chicago 101 Austin Weekly News 224 Catholic New World 101 Barrington Courier-Review 118, 128 Catholic News Service 109 Bartlett Examiner 136 CBS-TV 2, 8 Bartlett Press 117, 136 Champaign News Gazette 154 Batavia Republican 117, 136 Charleston Times-Courier 110, -

Sample Chapter

BUSINESS ENTREPRENEURS/ MEDIA frican Americans have a long and rich his- Virginia, is believed to be the first person of tory of entrepreneurship in America; African descent to have become an entrepreneur AAfrican Americans have been in business in America. Jean Baptist DuSable, a wholesaler since before the Civil War and continue their en- and merchant who established the first settle- trepreneurial tradition today. Segments of the ment in Chicago in the early 1770s, was another African American population have exhibited the pre-Civil War era entrepreneur. same entrepreneurial spirit as segments of other ethnic groups who have migrated to this coun- Prior to the Civil War, however, slavery de- try. Very often, however, the history of black en- fined the existence of most African Americans. trepreneurship has been either overlooked or Thus, two categories of business persons were misconstrued. able to develop and sustain business enterprises. The first group was composed of free African Americans, numbering approximately sixty thou- ENTREPRENEURS sand, who could accumulate the capital to gen- erate business activity. They developed ntrepreneurship for African Americans has enterprises in almost every area of the business incorporated ownership as a means to man- community, including merchandising, real estate, age and disseminate information for the E manufacturing, construction, transportation, and betterment of the community as well as a means extractive industries. to gain economic opportunities. African Ameri- can religious publishers were the first entrepre- The second group consisted of slaves who— neurs to represent African American interests as a result of thrift, ingenuity, industry, and/or the using print media. -

African Americans—Intellectual Life. Updated July 2014. MLA 6Th Edition

African Americans—Intellectual Life. Updated July 2014. MLA 6th edition. Paul Revere Williams Project. Art Museum of the University of Memphis. "13th Annual Conclave of Builders Will be Held at Hampton, Va." The New York Age February 13 1937, sec. 2:. "8 AIA Members are Advanced." Los Angeles Times May 12 1957: F19. "Abstracts of Papers Presented at the Twenty-Seventh Annual Meeting of the Society of Architectural Historians (Dozier, Richard K. "Black Craftsmen and Architects in History")." Journal of Architectural Historians 33.3 (1974): 225-243. "Ad for Castaic Country Club." California Eagle May 16 1924: 12. Adams, Michael. "Perspectives: Historical Essay, Black Architects - A Legacy of Shadows." Progressive Architecture (1991): 85-7. "Angelus Funeral Home; John Lamar Hill; Lorenzo Bowdoin." Negro Who's Who in California., 1948. 56,58. Angelus Funeral Home. Famous Black Angelinos (Louis M. Blodgett Page). Los Angeles: Angelus Funeral Home, 1984. "Anniversary of Building-Loan Co. Celebrated: Liberty's Growth is shown at 8th Birthday Ceremonies." California Eagle April 1 1932: 2. "Architecture." Encyclopedia of African American Society. Ed. Gerald D. Jaynes. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005. 52-54. Arthur, George Robert. "Instutional Case Studies: 28th St Branch." Life on the Negro Frontier. 1st ed. New York: Association Press, 1934. 143-206. "Arts & Entertainment: From Obscurity to Celebrityhood: Architecture." Black Firsts: 2,000 Years of Extraordinary Achievement. Ed. Jessie Carney Smith. Detroit, MI: Gale Research Inc., 1994. 1. Beavers, George, and Ranford B. Hopkins. In Quest of Full Citizenship: George Beavers (28th St. YMCA). Oral history transcipt ed. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA, 1882. -

Abstracting & Indexing Services

ABSTRACTING & INDEXING SERVICES SCULPTURE See also: BIBLIOGRAPHIES SMITHSONIAN STEP-BY-STEP GRAPHICS ADVERTISING & PUBLIC RELATIONS GRAPHIS (ENGLISH, FRENCH, GERMAN) ASTRONOMY ASTRONOMY AERONAUTICS & SPACE FLIGHT GRIFFITH OBSERVER AD ASTRA SKY & TELESCOPE AVIATION WEEK & SPACE TECHNOLOGY AUDIO-VISUAL EDUCATION AGRICULTURE See: EDUCATION See also: FOOD & FOOD INDUSTRY, FORESTS & FORESTRY AUTOMOBILES ORGANIC GARDENING See: TRANSPORTATION-- RODALE’S ORGANIC LIFE AUTOMOBILES SUCCESSFUL FARMING BANKING & FINANCE ANTHROPOLOGY See: BUSINESS & ECONOMICS-- See also: ARCHAEOLOGY BANKING & FINANCE AMERICAN ANTHROPOLOGIST JOURNAL OF CALIFORNIA & GREAT BIBLIOGRAPHIES BASIN ANTHROPOLOGY See also: ABSTRACTING & INDEXING SERVICES, ANTIQUES LIBRARY & INFORMATION See: HOBBIES--ANTIQUES SCIENCES, PUBLISHING & BOOK TRADE ARCHAEOLOGY CHOICE See also: ANTHROPOLOGY ARCHAEOLOGY BIOLOGY PACIFIC COAST ARCHAEOLOGICAL See also: CONSERVATION, QUARTERLY ENVIRONMENTAL STUDIES SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY MUSEUM BIOSCIENCE ASSOCIATION QUARTERLY DISCOVER SAN BERNARDINO COUNTY MUSEUMS SCIENCE NEWSLETTER SCIENCE NEWS ARCHITECTURE BUILDING & CONSTRUCTION See also: INTERIOR DESIGN & See also: ARCHITECTURE, DECORATION, HOUSING ENGINEERING, HOUSING & URBAN PLANNING & URBAN PLANNING ARCHITECTURAL DIGEST ARCHITECTURAL RECORD BUSINESS & ECONOMICS BETTER HOMES & GARDENS BLACK ENTERPRISE LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE BUSINESS WEEK ECONOMIST (BRITISH) ART FORBES AMERICAN ARTIST FORTUNE AMERICAN CRAFT NATION'S BUSINESS ART & ANTIQUES ART IN AMERICA BUSINESS & ECONOMICS--INTERNATIONAL ART JOURNAL -

Paper New Directions in African American Business History

Black Power in the Boardroom: Corporate America, the Sullivan Principles, and the Anti- Apartheid Struggle Jessica Ann Levy On the morning of March 1, 1971, Leon Sullivan dressed in a “new white shirt and black suit,” both “freshly cleaned and pressed,” put on his “uncharacteristically black-shined shoes,” and straightened his “new light gray tie.” He leaned down to kiss his wife, who, while not short by any means, was a good ten inches shorter than her husband, who towered over most people at six feet five inches. He walked out of his room at the Plaza Hotel in New York City and across Fifth Avenue to the General Motors Building, where he was to attend his first board meeting as a GM director.1 Figure 1: Left: General Motors Building at 767 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan, New York City. Right: Leon H. Sullivan At the time, Sullivan was among a handful of African Americans serving on the boards of Fortune 500 companies in the United States. Within days of General Motors’ historic 1 Sullivan, Moving Mountains, 1. Do not cite or circulate without the author’s prior written permission Black Power in the Boardroom appointment of Sullivan as the first African American director of a major corporation in early January 1971, the New York Federal Reserve Bank and W.T. Grant Company announced they had appointed National Urban League President Whitney Young and former North Carolina Mutual Insurance Company executive Asa Spaulding to their respective boards.2 Other companies and financial institutions soon followed suit. Whereas in 1969 there had been