Distribution and Habitat Selection of the Asian Openbill (Anastomus Oscitans)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kenyataan Tawaran Secara Undian (Khas Untuk Bumiputera)

LEMBAGA KEMAJUAN WILAYAH PULAU PINANG KEMENTERIAN PEMBANGUNAN LUAR BANDAR KENYATAAN TAWARAN SECARA UNDIAN (KHAS UNTUK BUMIPUTERA) 1. Tawaran adalah dipelawa kepada kontraktor-kontraktor yang berdaftar dengan CIDB dan PKK, memegang Perakuan Pendaftaran, Sijil Perolehan Kerja Kerajaan dan Sijil Taraf Bumiputera di Daerah Seberang Perai Tengah, Pulau Pinang sahaja bagi melaksanakan kerja-kerja berikut :- CADANGAN MEMBINA DAN MENYIAPKAN RUMAH SERTA (i) TAJUK CABUTAN UNDI PEMBAIKAN RUMAH DI BAWAH PROGRAM PERUMAHAN RAKYAT TERMISKIN (PPRT) SKIM PEMBANGUNAN KESEJAHTERAAN RAKYAT (RMK-11) (ii) NO. CABUTAN UNDI PERDA/BHT/U/15/2020 i. Peserta 1 : NORMA BINTI RAMLI (BINA BARU) Alamat : 6131-A KG TELUK BUKIT, CHEROK TOKUN, BUKIT MERTAJAM PERDA/BHT/U/16/2020 ii. Peserta 2 : MAT ISA BIN PIEE (PEMBAIKAN) Alamat : NO.457, MUKIM 12, LORONG SEMBILANG 3, JALAN SUNGAI SEMBILANG PERDA/BHT/U/17/2020 iii. Peserta 3 : AZALI BIN AHMAD (PEMBAIKAN) Alamat :5202, KAMPUNG BESAR, PERMTANG PAUH iv. Peserta 4 : AHMAD BIN KHAMIS PERDA/BHT/U/18/2020 Alamat : 514, MK 4, PERMATANG TENGAH, PERMATANG (PEMBAIKAN) PAUH PERDA/BHT/U/19/2020 v. Peserta 5 : ABD RAHIM BIN ISMAIL (PEMBAIKAN) Alamat :TS 7031, PERMATANG TENGAH, KUBANG ULU PERDA/BHT/U/20/2020 vi. Peserta 6 : AZIZAH BINTI DIN (PEMBAIKAN) Alamat : NO. 2528 MUKIM 2, TANJUNG PUTUS, PERMATANG PASIR vii. Peserta 7 : HASSAN BIN JAMALUDIN PERDA/BHT/U/21/2020 Alamat : NO. 1287 MK 4, TALI AIR, PERMATANG PAUH (PEMBAIKAN) PERDA/BHT/U/22/2020 viii. Peserta 8 : NORAZLI BIN AHMAD (PEMBAIKAN) ix. Alamat : TS 4349, JALAN SAMA GAGAH, PERMATANG PAUH PERDA/BHT/U/23/2020 x. Peserta 9 : SITI SA’ADIAH BINTI BAKAR (PEMBAIKAN) Alamat : 2603, MK 3, KAMPUNG PETANI, BUKIT MERTAJAM xi. -

Fax : 04-2613453 Http : // BIL NO

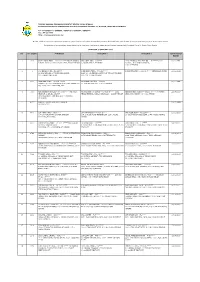

TABUNG AMANAH PINJAMAN PENUNTUT NEGERI PULAU PINANG PEJABAT SETIAUSAHA KERAJAAN NEGERI PULAU PINANG TINGKAT 25, KOMTAR, 10503 PULAU PINANG Tel : 04-6505541 / 6505599 / 6505165 / 6505391 / 6505627 Fax : 04-2613453 Http : //www.penang.gov.my Berikut adalah senarai nama peminjam-peminjam yang telah menyelesaikan keseluruhan pinjaman dan tidak lagi terikat dengan perjanjian pinjaman penuntut Negeri Pulau Pinang Pentadbiran ini mengucapkan terima kasih di atas komitmen tuan/puan di dalam menyelesaikan bayaran balik Pinjaman Penuntut Negeri Pulau Pinang SEHINGGA 31 JANUARI 2020 BIL NO AKAUN PEMINJAM PENJAMIN 1 PENJAMIN 2 TAHUN TAMAT BAYAR 1 371 QUAH LEONG HOOI – 62121707**** NO.14 LORONG ONG LOKE JOOI – 183**** TENG EE OO @ TENG EWE OO – 095**** 4, 6TH 12/07/1995 SUNGAI BATU 3, 11920 BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU PINANG. 6, SOLOK JONES, P PINANG AVENUE, RESERVOIR GARDEN , 11500 P PINANG 2 8 LAU PENG KHUEN – 51062707 KHOR BOON TEIK – 47081207**** CHOW PENG POY – 09110207**** MENINGGAL DUNIA 31/12/1995 62 LRG NANGKA 3, TAMAN DESA DAMAI, BLOK 100-2A MEWAH COURT, JLN TAN SRI TEH EWE 14000 BUKIT MERTAJAM LIM, 11600 PULAU PINANG 3 1111 SOO POOI HUNG – 66121407**** IVY KHOO GUAT KIM – 56**** - 22/07/1996 BLOCK 1 # 1-7-2, PUNCAK NUSA KELANA CONDO JLN 10 TMN GREENVIEW 1, 11600 P PINANG PJU 1A/48, 47200 PETALING JAYA 4 343 ROHANI BINTI KHALIB – 64010307**** NO 9 JLN MAHMUD BIN HJ. AHMAD – 41071305**** 1962, NOORDIN BIN HASHIM – 45120107**** 64 TAMAN 22/07/1997 JEJARUM 2, SEC BS 2 BUKIT TERAS JERNANG, BANGI, SELANGOR. - SUDAH PINDAH DESA JAYA, KEDAH, 08000 SG.PETANI SENTOSA, BUKIT SENTOSA, 48300 RAWANG, SELANGOR 5 8231 KHAIRIL TAHRIRI BIN ABDUL KHALIM – - - 16/03/1999 80022907**** 6 7700 LIM YONG HOOI – A345**** LIM YONG PENG – 74081402**** GOH KIEN SENG – 73112507**** 11/11/1999 104 18-A JALAN TAN SRI TEH, EWE LIM, 104 18-A JLN T.SRI TEH EWE LIM, 11600 PULAU 18-I JLN MUNSHI ABDULLAH, 10460 PULAU PINANG 11600 PULAU PINANG PINANG 7 6605 CHEAH KHING FOOK – 73061107**** NO. -

Than Hsiang Temple: from Womb to Tomb Soong Wei Yean, M.A

Ms. Soong Wei Yean from Malaysia was a former school teacher. Her academic interest in Buddhism started in 1996 when she joined the Than Hsiang Buddhist Research Centre to pursue a Diploma in Buddhism and later graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in Buddhist Studies in 2002 as an external candidate of the Pali and Buddhist University of Sri Lanka. Upon her retirement as school senior assistant, she further pursued Buddhist Studies and graduated with an MA from the International Buddhist College, Thailand in 2013. She has presented papers at the World Buddhist University Conferences. She is currently a PhD student of the International Buddhist College and continues to cultivate the Buddha’s path of spiritual progress. Than Hsiang Temple: From Womb to Tomb Soong Wei Yean, M.A. International Buddhist College, Thailand [email protected] ABSTRACT Than Hsiang Temple established in the 90’s by Ven Wei Wu subscribes to the 4 Pillars of Conviction: “The Young to Learn The Strong and Healthy to Serve The Aged and Sick to be Cared for The Departed to Find Spiritual Destination.” With these as the guiding principles, all the Temple activities are aimed at promoting Buddhist education, welfare and cultivation. The temple provides preschool education, Sunday school and weekly Dhamma class; supports the Phor Tay School and the International Buddhist College to promote Buddhist education. The people’s welfare is taken care of by the Mitra counselling department, Free Metta Clinic, Wan Ching Yuan old folks home, daily vegetarian food based on donation and monthly visits to the poor to provide basic necessities. -

Seberang Perai Utara

SEBERANG PERAI UTARA KOD KAWASAN PETAK KERETA SPU 1 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 3843 -3851 Jalan Bagan Luar 7 SPU 2 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4873 -4876 Jalan Bagan Luar 14 SPU 3 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4105 -4114 Jalan Bagan Luar 17 SPU 4 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4144-4223 Jalan Bagan Luar 11 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4703 hingga 4710, 4422 hingga 4425 & 4802 Jalan SPU 5 53 Bagan Luar SPU 6 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4451 -4454 Jalan Bagan Luar 4 SPU 7 Jalan Pasar termasuk jalan susur di hadapan Kompleks MARA 52 SPU 8 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 3635 – 4921 Jalan Bagan Luar 51 SPU 9 Sekitar bangunan No. 3914 – 4277 Jalan Bagan Luar 44 SPU 10 Lorong Bagan Luar 1 21 SPU 11 Lorong Bagan Luar 2 61 SPU 12 Lorong Bagan Luar 3 25 SPU 13 Lorong Bagan Luar 4 3 SPU 14 Jalan Kampong Banggali 219 SPU 15 Jalan Telekom 19 SPU 16 Jalan Pantai 113 SPU 17 Taman Selat 303 SPU 18 Jalan Kampong Jawa & Lorong Kampong Jawa 64 SPU 19 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4768 – 4777 Jalan Bagan Luar 25 SPU 20 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 3838 – 4072 Jalan Bagan Luar 47 SPU 21 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 1 – 79 Jalan Kapal 41 SPU 22 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4654 – 4679 Jalan Chain Ferry 77 SPU 23 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. 4803 – 4807 Jalan Chain Ferry 11 SPU 24 Jalan susur di hadapan Bangunan No. -

The State of Penang, Malaysia

Please cite this paper as: National Higher Education Research Institute (2010), “The State of Penang, Malaysia: Self-Evaluation Report”, OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development, IMHE, http://www.oecd.org/edu/imhe/regionaldevelopment OECD Reviews of Higher Education in Regional and City Development The State of Penang, Malaysia SELF-EVALUATION REPORT Morshidi SIRAT, Clarene TAN and Thanam SUBRAMANIAM (eds.) Directorate for Education Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education (IMHE) This report was prepared by the National Higher Education Research Institute (IPPTN), Penang, Malaysia in collaboration with a number of institutions in the State of Penang as an input to the OECD Review of Higher Education in Regional and City Development. It was prepared in response to guidelines provided by the OECD to all participating regions. The guidelines encouraged constructive and critical evaluation of the policies, practices and strategies in HEIs’ regional engagement. The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the National Higher Education Research Institute, the OECD or its Member countries. Penang, Malaysia Self-Evaluation Report Reviews of Higher Education Institutions in Regional and City Development Date: 16 June 2010 Editors Morshidi Sirat, Clarene Tan & Thanam Subramaniam PREPARED BY Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang Regional Coordinator Morshidi Sirat Ph.D., National Higher Education Research Institute, Universiti Sains Malaysia Working Group Members Ahmad Imran Kamis, Research Centre and -

SENARAI PREMIS PENGINAPAN PELANCONG : P.PINANG 1 Berjaya Penang Hotel 1-Stop Midlands Park,Burmah Road,Timur Laut 10350 Timur La

SENARAI PREMIS PENGINAPAN PELANCONG : P.PINANG BIL. NAMA PREMIS ALAMAT POSKOD DAERAH 1 Berjaya Penang Hotel 1-Stop Midlands Park,Burmah Road,Timur Laut 10350 Timur Laut 2 The Bayview Beach Resort 25-B,Lebuh Farquha, Timur Laut 10200 Timur Laut 3 Evergreen Laurel Hotel 53, Persiaran Gurney 10250 Georgetown 4 CITITEL PENANG 66,Jln Penang 10000 Georgetown 5 Oriental Hotel 105, Jln Penang 10000 Georgetown 6 Sunway Hotel Georgetown 33, Lorong Baru, Off Jln Macalister 10400 Georgetown 7 Sunway Hotel Seberang Jaya No.11, Lebuh Tenggiri 2, Pusat Bandar Seberang Jaya 13700 Seberang Jaya 8 Hotel Neo + Penang No.68 Jalan Gudwara, Town Pulau Pinang 10300 Georgetown 9 Golden Sand Resort Penang By Shangri-La 10th Mile, Batu Ferringhi, Timur Laut 11100 Batu Ferringhi 10 Bayview Hotel Georgetown Penang 25-A, Farquhar Street 10200 Georgetown 11 Park Royal Penang Resort Batu Ferringhi 11100 Batu Ferringhi 12 Hotel Sri Malaysia Penang No.7,Jln Mayang Pasir 2 11950 Bandar Bayan Baru 13 Rainbow Paradise Beach Resort 527,Jln Tanjung Bungah 11200 Tanjung Bungah 14 Equatorial Hotel Penang No.1,Jln Bukit Jambul 11900 Bayan Lepas 15 Shangri-La's Rasa Sayang Resort & Spa Batu Ferringhi Beach 11100 Batu Ferringhi 16 Hotel Continental No.5, Jln Penang 10000 Georgetown 17 Hotel Noble 36,Lorong Pasar 10200 Georgetown 18 Pearl View Hotel 2933, Jln Baru 13600 Butterworth 19 Eastern and Oriental Hotel 10, Leboh Farquhar 10200 Georgetown 20 Modern Hotel 179-C, Labuh Muntri 10200 Georgetown 21 Garden Inn 41, Anson Road 10400 Georgetown 22 Pin Seng Hotel 82, Lorong Cinta 10200 Georgetown 23 Hotel Eng Loh 48, Church Street 10200 Georgetown 24 Hotel Apollo 4475, Jln Kg. -

Permatang Pauh Nilai Kontrak KN Oleh : AINUL WARDAH SOHILLI

Kompleks Rumah, jangan Pagi Bebas Sukan anak tiri Kenderaan Bandaraya di Seberang P. Pinang Relau MS 6 MS 6 & 9 Perai MS 20 buletin www.buletinmutiara.com 1 – 15 MEI 2015 Kontraktor Bumiputera dapat 94% daripada Permatang Pauh nilai kontrak KN Oleh : AINUL WARDAH SOHILLI GEORGE TOWN – Jumlah kontrak dikeluarkan Oleh mahukan: PR - KM Kerajaan Negeri Pakatan Rakyat (PR) Pulau ZAINULFAQAR Pinang sebanyak RM8.3 bilion sepanjang tujuh YAACOB tahun sejak 2008 adalah lebih besar daripada keseluruhan nilai projek yang diberikan sepanjang GEORGE TOWN 50 tahun oleh Kerajaan Negeri Barisan Nasional – Ahli Parlimen (BN) sebelum 2008. Daripada nilai projek RM8.3 bilion tersebut, Bagan yang juga RM7.8 bilion diberikan secara tender kompetitif Ketua Menteri, terbuka, manakala bakinya sebanyak RM496 juta Y.A.B. Tuan adalah secara sebutharga. Lim Guan Eng Perkara tersebut dinyatakan Ketua Menteri, menyatakan bahawa Y.A.B. Tuan Lim Guan Eng dalam kenyataan kemenangan di bertulisnya dan juga sidang akhbar yang diadakan Permatang Pauh di sini baru-baru ini. membuktikan Katanya, RM7.8 bilion atau 94 peratus bahawa majoriti daripada nilai projek Kerajaan Negeri berjumlah pengundi-pengundi keseluruhan RM8.3 bilion telah diberikan kepada Permatang Pauh kontraktor Bumiputera. khususnya mahukan "Ini sekaligus menangkis fitnah dan penipuan sebuah Pakatan oleh pemimpin UMNO dan BN yang cuba Rakyat (PR) yang mainkan sentimen perkauman bahawa kontraktor kuat. Bumiputera tidak dijaga oleh Kerajaan Negeri “Jelas sekali isu atau tak mendapat kontrak Kerajaan Negeri PR" nasional seperti DR. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail (depan, bertudung putih), Ketua Menteri dan barisan kepimpinan tegas beliau. GST (Cukai barangan Kerajaan Negeri bersama-sama meraikan kemenangan keputusan PRK P.044 Parlimen Permatang Guan Eng memberitahu, kemampuan dan perkhidmatan), Pauh di Institut Kemahiran Belia Negara (IKBN) di sini baru-baru ini. -

Safety and Operational Performance of Roundabouts

International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology (IJEAT) ISSN: 2249 – 8958, Volume-8, Issue-6S3, September 2019 Safety and Operational Performance of Roundabouts Li-Sian Tey, M. S. Salim, Shahreena Melati Rhasbudin Shah, Prakash Ranjitkar control [3]-[6]. The conventional multilane roundabout has Abstract: When there are two or more roads meet, there is become an effective solution to cope with relatively high higher tendency of conflicts among vehicles. Roundabout is not traffic demands. However, the additional entry and a new concept to manage conflict points at at-grade intersection. circulatory lanes increase the safety problems as well. These However, improper motorist behaviours especially during peak problems mostly are the effect of improper driving behaviour hour affect safety and operational performance of a roundabout. of drivers in the roundabout including entry and in This paper compares the safety and operational performance circulatory. Previous studies on two-lane roundabouts evaluation of a conventional non-signalized roundabout and a encountered improper behaviour as being common practice, conventional signalised roundabout and explores the potential of turbo roundabout to replace the conventional ones. Three resulting in conflicts and increased likelihood of crashed [7]. characteristics used to evaluate safety performance of the Failure to give signals/indicators during merging and roundabouts include entry lane selection, use of entry and exit diverging in the roundabout’s circulatory might be one of the indicators, and weaving activities. These behaviours create the causes of accident. On top of that, inexperienced driver might possibility of conflict, hence, risk of fatalities. On the other hand, have problems to decide which lane should be their entry delay and total time travel are used as indicators of operational resulting in need of weaving which then cause other vehicle performance of the roundabouts. -

Permatang Pauh 'Yes' to PR

THUMBS-UP pg FOR HILL 1 CABLE CAR pg 2 槟去年制造业投资额创82亿令吉记录 FREE buletin Competency Accountability Transparency http:www.facebook.com/buletinmutiara May 1 - 15, 2015 http:www.facebook.com/cmlimguaneng Permatang Pauh ‘yes’ to PR Story by Mark James Pix by Shum Jian-Wei IT was not unexpected but when Datuk Seri Dr. Wan Azizah Wan Ismail was declared winner of the Perma- tang Pauh by-election on May 7, cheers of joy rang out from leaders and supporters alike. Speaking at a press conference on May 8, Chief Minister Lim Guan Eng said that the Permatang Pauh voters preferred the united and people-centric policies of the PR Penang state government. “Despite claims of no development in Permatang Pauh, the Penang state government has poured more than RM70 million in direct cash aid and development funds since 2008, or an average of RM10 million an- nually,” he said. “Not only did the rakyat receive money for the first time, Permatang Pauh voters saw the best community hall built by the state government in Seberang Jaya, repainted mosques and new roads all completed before the by-election. The state government will continue this Wan Azizah celebrates her victory with (from left) PAS deputy president Mohamad Sabu, Lim and Selangor commitment of serving the rakyat at all times and not Mentri Besar Azmin Ali who is PKR deputy president. only five years once during elections,” he added. In terms of financial standing and development, Lim Azman Shah and Salleh lost their deposits. vote here too! I tried to get a photo with her but there said that the state awarded a total of RM7.8 billion out This by-election marked Wan Azizah’s fourth term were just too many supporters crowding around her,” of RM8.3 billion or 94% of contracts to bumiputera as Permatang Pauh MP after her husband Datuk Seri said an ecstatic 24-year-old who only wished to be contractors under open competitive tenders, thus silenc- Anwar Ibrahim was jailed in February. -

List of Certified Workshops-Final

PULAU PINANG: SENARAI BENGKEL PENYAMAN UDARA KENDERAAN YANG BERTAULIAH (LIST OF CERTIFIED MOBILE AIR-CONDITIONING WORKSHOPS) NO NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT POSKOD DAERAH/BANDAR TELEFON NAMA & K/P COMPANY NAME ADDRESS POST CODE DISTRICT/TOWN TELEPHONE NAME& I/C 1 PERFECT AUTO ELECTRICAL NO. 1273-A, PAYA TERUBONG 11060 AYER ITAM TEL : 04-8272892 QUAH KUNG HOOI SERVICES ROAD, 11060 AYER ITAM, 680923-07-5193 PENANG. 2 TEOH AUTO ACCESSORIES & AIR- 87-Z, JALAN KAMPUNG 11500 AYER ITAM TEL: 04-8297673 TEOH THEAN HUAT COND TRADING. PISANG, 11500 AYER ITAM, 651113-07-5869 PENANG. 3 ISLAND CAR-COOLER & AUTO 3E, JALAN THEAN TEIK, AYER 11400 AYER ITAM TEL: 04-8260817 WONG MUN CHEONG ACCESSORIES. ITAM, 11400 PENANG. H/P: 012-4721690 640206-08-5827 4 RONSON AUTO ACCESSORIES & 247, JALAN SUNGAI PINANG, 11000 BALIK PULAU TEL : 04-8660064 QUEK CHAI PENG AIR COND SERVICES BALIK PULAU, 11000 PULAU 580909-07-5017 PINANG. 5 TEE HENG CAR AIR-COND BDKTN 297, PAYA KONGSI MK 11000 BALIK PULAU H/P : 016-4896661 YONG HAI ENG ACCESSORIES M-F, BALIK PULAU 760730-01-5127 6 MEICONNAX CAR AIR-COND & 10 TINGKAT, TELUK KUMBAR 11920 BANDAR BARU TELUK H/P : 012-4306200 CHEN CHEE CHEW ACCESSORIES 4, BANDAR BARU TELUK KUMBAR 791009-07-5097 KUMBAR, 11920 PULAU PINANG. 1 PULAU PINANG: SENARAI BENGKEL PENYAMAN UDARA KENDERAAN YANG BERTAULIAH (LIST OF CERTIFIED MOBILE AIR-CONDITIONING WORKSHOPS) NO NAMA SYARIKAT ALAMAT POSKOD DAERAH/BANDAR TELEFON NAMA & K/P COMPANY NAME ADDRESS POST CODE DISTRICT/TOWN TELEPHONE NAME& I/C 7 LEAN HOCK CAR AIR-COND 9, BARRACK ROAD, 10450 10450 BARRACK ROAD TEL: 04-2284586 ONG KAI MIN SERVICES. -

Pengerusi PERSATUAN TARIAN SINGA JONG HWA, SEBERANG PERAI, PULAU PINANG 733, Mukim 8,Kg

Pengerusi PERSATUAN TARIAN SINGA JONG HWA, SEBERANG PERAI, PULAU PINANG 733, Mukim 8,Kg. Cross Street,14000, Bukit Mertajam,Seberang Perai Tgh,Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERSATUAN TARIAN SINGA KUAN ENG, SEBERANG PERAI PULAU LINANG Lot 1262,MK 20,Jln Penanti,Kubang Semang,Bukit Mertajam,14400,Seberang Perai Tgh, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERTUBUHAN AKADEMI TARIAN GALAXIE (THE PENANG PERAI GALAXIE DANCE ACADEMY ASSOCIATION) No.03A-03,Pangsapuri Prima Aman,Lrg Perai Utama 8,13600 Perai,Seberang Perai, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERSATUAN KESENIAN NOISE PULAU PINANG H-3-4, Taman Desa Relak, Lebuh Relak 2, 11900 Bayan Lepas, Pulau Pinang. Pengerusi NAVARAAGAS INDIAN TRADITIONAL MUSIC No.70-Z,Mount Erskine,10470 Pulau Pinang Pengerusi SRI JAYAM URUMEE MELAM No.72-12-04,Jln Tgh,11900,Bayan Baru, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi CHING XING SPORTS CULTURAL CENTRE No.3-Q,Jln Semarak Api,Bdr Baru,11500, Ayer Itam (Farlim),Pulau Pinang Pengerusi MUZIK TRADISIONAL CINA Telefon 012-5766583 Pengerusi PERTUBUHAN MUZIK TIONGHUA MALAYSIA UTARA No.32,Jln Manggis,Tmn Bak Hai Bukit Mertajam,14000,Seberang Perai Tgh,Pulau Pinang Pengerusi KELAB SAHABAT KLASIK PULAU PINANG Q-G-04,Pangsapuri Permata,Bdr Perda Bukit Mertajam,14000,Seberang Perai, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERSATUAN PEMUZIK-PEMUZIK TRADISIONAL NATHESWARAN DAN THAVIL,SEBERANG PERAI PULAU PINANG No.46,Lrg Damai 2,Tmn Permata, Bukit Mertajam,14000,Seberang Perai Tgh, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERSATUAN KESENIAN SRI SELVA VINAYAGAR URUMI MELAM PMT MB-03-23,Pangsapuri Delima Intan, Jln Seri Delima 1,Tmn Seri Delima Bukit Mertajam,14000,Seberang Perai Tgh, Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PENANG INCLUSION ORCHESTRA 245,Lrg Sri Kijang 10,Tmn Seri Kijang Pulau Pinang Pengerusi PERTUBUHAN PEMUZIK DAN DRAMA PULAU PINANG (PENANG PLAYERS MUSIC + DRAMA SOCIETY) 25, Jalan Bungah Cempak Puteh, Hillside, Tanjung Bungah, 11200 Pulau Pinang. -

Senari Pusat Tahfiz

SENARAI PUSAT TAHFIZ AL-QURAN NEGERI PULAU PINANG NO. TEL SEK & BIL NAMA SEKOLAH ALAMAT KOD PENDAFTARAN NAMA MUDIR DAERAH EMAIL FAX NO.247 LOT 267 MUKIM 3, JALAN 04-8663221 MADRASAH MIFTAHUL US. SHAMSUDIN B. [email protected] 1 SUNGAI PINANG, 11010 BALIK JAIPP/PEND/01-BD-( R ) 014 016-4409418 BD IRFAN HASSAN m PULAU, PULAU PINANG LOT 172, MUKIM 3, SUNGAI UST. AZMAN B. 2 TAHFIZ DARUL FURQAN RUSA,11010 BALIK PULAU, JAIPP/PEND/01-BD-( R )0020 019-409 1986 BD [email protected] SULTANUL ARIFFIN PULAU PINANG MADRASAH TAHFIZ NO.20, SOLOK RAJAWALI 5, HJ. YUSOFF BIN 3 DARUS SA’ADAH JAIPP/PEND/01-BD-( R ) 0027 013-430 4610 BD [email protected] 11900 BAYAN LEPAS, P.PINANG. RAHMAN SHA NO.43, LEBUH BATU MAUNG MA’HAD TAHFIZ HJ. MOHD FAUZI B. 4 4,11960 BAYAN LEPAS, PULAU JAIPP/PEND/01-BD-( R )0023 012-5147981 BD MANAHILIL IRFAN AHMAD PINANG MADRASAH TAHFIZ 17-A, JALAN BUNGA RAYA, US. MOHAMAD 5 DARUL UKASHA BUKIT GELUGOR,11700 JAIPP/PEN/02-TL-( R ) 021 SALIM B. SAUROO 012-4444262 TL GELUGOR, PULAU PINANG MYDIN MAAHAD TAHFIZ 407, JALAN PERAK, 11600 UST. NORHISHAM 6 JAIPP/PEND/02-TL-( R ) 016 019-726 7435 TL FATHURRAHMAN JELUTONG, PULAU PINANG BIN IBRAHIM MADRASAH TAHFIZ AL- SURAU KAMPUNG KASTAM, DR. 04-6590790 7 QURANUL KARIM BAITUL JALAN LEMBAH,11700 BUKIT JAIPP/PEND/02-TL-( V ) 004 NAJIBURRAHMAN B. 017-4524485 TL IRFAN GELUGOR, PULAU PINANG HANNIF BABA MA’HAD TAHFIZ AL- MASJID TERAPONG, TANJONG US. HANAFI B. 8 QURAN KASYFU AL- BUNGA, JAIPP/PEND/02-TL-( R ) 019 017-458 5639 TL OSMAN ULUM 11200 PULAU PINANG SURAU ABU BAKAR AS SIDDEK, MADRASAH DARUL UST.