Prudhoe Historic Characterisation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fantastic W Ays to Travel and Save Money with Go North East Travelling with Uscouldn't Be Simpler! Ten Services Betw Een

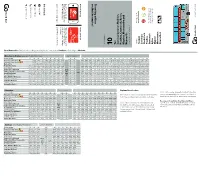

money with Go North East money and save travel to ways Fantastic couldn’t be simpler! couldn’t with us Travelling gonortheast.co.uk the Go North East app. mobile with your to straight times and tickets Live Go North app East Get in touch gonortheast.co.uk 420 5050 0191 @gonortheast simplyGNE 5 mins 5 mins gonortheast.co.uk /gneapp Buses run up to Buses run up to 30 minutes every ramp access find You’ll bus and travel on every on board. advice safety gonortheast.co.uk smartcard. deals on exclusive with everyone, easier for cheaper and travel Makes smartcard the key /thekey the key the key Serving: Hexham Corbridge Stocksfield Prudhoe Crawcrook Ryton Blaydon Metrocentre Newcastle Go North East 10 Bus times from 21 May 2017 21 May Bus times from Ten Ten Hexham, between Services Ryton, Crawcrook, Prudhoe, and Metrocentre Blaydon, Newcastle 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Crawcrook » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Every 30 minutes at Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10X 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle Eldon Square - 0623 0645 0715 0745 0815 0855 0925 0955 25 55 1355 1425 1455 1527 1559 1635 1707 1724 1740 1810 1840 1900 1934 1958 2100 2200 2300 Newcastle Central Station - 0628 0651 0721 0751 0821 0901 0931 1001 31 01 1401 1431 1501 1533 1606 1642 1714 1731 1747 1817 1846 1906 1940 2003 2105 2205 2305 Metrocentre - 0638 0703 0733 0803 0833 0913 0944 1014 44 14 1414 1444 1514 1546 1619 1655 1727 X 1800 1829 1858 1919 1952 2016 2118 2218 2318 Blaydon -

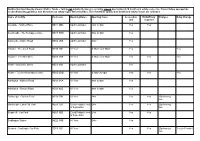

Public Toilet Map NCC Website

Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. Please follow appropriate social distancing guidance and directions on safety signs at the facilities. This list will be updated as health and safety issues are reviewed. Name of facility Postcode Opening Dates Opening times Accessible RADAR key Charges Baby Change unit required Allendale - Market Place NE47 9BD April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Yes Allenheads - The Heritage Centre NE47 9HN April to October 7am to 4pm Yes Alnmouth - Marine Road NE66 2RZ April to October 24hr Yes Alnwick - Greenwell Road NE66 1SF All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Alnwick - The Shambles NE66 1SS All Year 6:30am to 6:30pm Yes Yes Yes Amble - Broomhill Street NE65 0AN April to October Yes Amble - Tourist Information Centre NE65 0DQ All Year 6:30am to 6pm Yes Yes Yes Ashington - Milburn Road NE63 0NA All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Ashington - Station Road NE63 9UZ All Year 8am to 4pm Yes Bamburgh - Church Street NE69 7BN All Year 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty box Bamburgh - Links Car Park NE69 7DF Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes 20p honesty of September box Beadnell - Car Park NE67 5EE Good Friday to end 24hr Yes Yes of September Bedlington Station NE22 5HB All Year 24hr Yes Berwick - Castlegate Car Park TD15 1JS All Year Yes Yes 20p honesty Yes (in Female) box Northumberland County Council Public Tolets - Toilets not detailed below are currently closed due to Covid-19 health and safety concerns. -

Trains Tyne Valley Line

From 15th May to 2nd October 2016 Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Northern Mondays to Fridays Gc¶ Hp Mb Mb Mb Mb Gc¶ Mb Sunderland dep … … 0730 0755 0830 … 0930 … … 1030 1130 … 1230 … 1330 Newcastle dep 0625 0646 0753 0824 0854 0924 0954 1024 1054 1122 1154 1222 1254 1323 1354 Dunston 0758 0859 Metrocentre 0634 0654 0802 0832 0903 0932 1002 1033 1102 1132 1202 1232 1302 1333 1402 Blaydon 0639 | 0806 | 1006 | | 1206 | | 1406 Wylam 0645 0812 0840 0911 1012 1110 1212 1310 1412 Prudhoe 0649 0704 0817 0844 0915 0942 1017 1043 1114 1142 1217 1242 1314 1344 1417 Stocksfield 0654 | 0821 0849 0920 | 1021 | 1119 | 1221 | 1319 | 1421 Riding Mill 0658 | 0826 | 0924 | 1026 | 1123 | 1226 | 1323 | 1426 Corbridge 0702 0830 0928 1030 1127 1230 1327 1430 Hexham arr 0710 0717 0838 0858 0937 0955 1038 1055 1137 1155 1238 1255 1337 1356 1438 Hexham dep … 0717 … 0858 … 0955 … 1055 … 1155 … 1255 … 1357 … Haydon Bridge … 0726 … 0907 … | … 1104 … | … 1304 … | … Bardon Mill … 0733 … 0914 … … 1111 … … 1311 … … Haltwhistle … 0740 … 0921 … 1014 … 1118 … 1214 … 1318 … 1416 … Brampton … 0755 … 0936 … | … 1133 … | … 1333 … | … Wetheral … 0804 … 0946 … … 1142 … … 1342 … … Carlisle arr … 0815 … 0957 … 1046 … 1157 … 1247 … 1354 … 1448 … Mb Mb Wv Mb Gc¶ Mb Ct Mb Sunderland dep … 1430 … 1531 … 1630 … … 1730 … 1843 1929 2039 2211 Newcastle dep 1424 1454 1524 1554 1622 1654 1716 1724 1754 1824 1925 2016 2118 2235 Dunston 1829 Metrocentre 1432 1502 1532 1602 1632 1702 1724 1732 1802 1833 1934 2024 2126 2243 Blaydon | | 1606 -

Weekly List of Planning Applications

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/03064/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr Daniel Kemp Agent: Mr Adam Barrass Keepwick Farm, Humshaugh, 16/17 Castle Bank, Tow Law, Hexham, Bishop Auckland, DL13 4AE, Proposal: Proposal for the construction of a four bedroomed agricultural workers dwelling adjacent to existing agricultural building Location: Land North West Of Carterway Heads, Carterway Heads, Northumberland Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. 9, 2019 Expiry Date: Nov. 3, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Melanie Francis Decision Level: Ward: South Tynedale Parish: Shotley Low Quarter Application No: 19/03769/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: Sept. 9, 2019 Applicant: Mr & Mrs Glenn Holliday Agent: Earle Hall 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ridley House, Ridley Avenue, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Blyth, Northumberland, NE24 3BB, Proposal: Proposed dining room extension; garden room; rooms in roof space with dormer windows Location: 12 Birney Edge, Darras Hall, Ponteland, NE20 9JJ Neighbour Expiry Date: Sept. -

Retail Roadside Scheme Now Open New Build Units to Let

RETAIL ROADSIDE SCHEME NOW OPEN JOIN ALDI, B&M HOMESTORE AND MCDONALD’S AVAILABLE UNITS FROM 3,425 SQ FT TO 20,000 SQ FT (320 SQ M TO 1,858 SQ M) ADJOINING DEVELOPMENT PLOT 2.3 ACRES (0.9HA) FOR SALE OR TO LET PRINCESS WAY, PRUDHOE, NORTHUMBERLAND, NE42 6PX NEW BUILD UNITS TO LET AND DEVELOPMENT PLOT FOR SALE/ TO LET TYNEVIEW RETAIL PARK 02 CONTENTS 03 LOCATION 04 OCCUPIERS 05 MASTERPLAN 06 STATS 07 TRACK RECORD 08 CONTACT TYNEVIEW RETAIL PARK 03 BLYTH LOCATION Bedlington A189 Cramlington A1 Seaton Delaval NEWCASTLE UPON TYNE 10.4 MILES - 24 MIN BY CAR Dudley GATESHEAD Whitley Bay A696 A186 11.7 MILES - 23 MIN BY CAR Newcastle A19 Airport BLAYDON Shiremoor KINTN A191 6 MILES - 12 MIN BY CAR RETAIL PARK HEXHAM Tynemouth Port of A1 Longbenton Tyne 13.4 MILES - 22 MIN BY CAR North Shields A191 SOUTH Gosforth A1058 SHIELDS A69 A167 Wallsend TYNE A68 TUNNEL A69 NEWCASTLE A69 UPON TYNE Hebburn Hexham Corbridge A1300 PRUDHOE Blaydon A184 A19 GATESHEAD A1018 A694 A68 A1 A692 A1290 A1231 TYNEVIEW RETAIL PARK 04 WEST SITE DEVELOPMENT PLOT OCCUPIERS TO LET T R P is the first phase of a proposed new retail and roadside TO LET development fronting A695 Princess Way to the north of Prudhoe town centre and extending to 66,865 sq ft approximately with TO LET 384 car park spaces. Aldi, B&M Homestore and Café Ginevra now open. Further new lettings agreed with McDonald’s Drive Thru, Greggs and BJC Kitchens. The west site totals 2.3 acres (0.9 ha) and has outline planning for a 19,375 sq ft hotel, 8,384 sq ft pub and 3,229 sq ft fuel filling station. -

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays

Sunderland - Newcastle - Hexham - Carlisle Sundays Middlesbrough d - - 0832 - - 0931 - - 1031 - Hartlepool d - - 0903 - - 1001 - - 1101 - Horden d - - 0914 - - 1012 - - 1112 - Sunderland d - - 0932 - - 1030 - - 1130 - Newcastle a - - 0951 - - 1050 - - 1150 - d 0845 0930 0955 1016 1035 1055 1115 1133 1155 1215 Dunston - 0935 - 1021 - - 1121 - - 1220 MetroCentre a 0852 0939 1002 1025 1043 1102 1124 1141 1202 1224 d 0853 - 1003 - - 1103 - - 1203 - Blaydon 0857 - 1007 - - - - - 1207 - Wylam 0903 - 1013 - - 1111 - - 1213 - Prudhoe 0908 - 1017 - - 1115 - - 1218 - Stocksfield 0912 - 1022 - - 1120 - - 1222 - Riding Mill 0917 - 1026 - - 1124 - - 1227 - Corbridge 0921 - 1030 - - 1128 - - 1231 - Hexham a 0927 - 1036 - - 1134 - - 1237 - d 0927 - 1037 - - 1135 - - 1237 - Haydon Bridge 0937 - 1046 - - 1144 - - - - Bardon Mill 0943 - 1052 - - 1150 - - - - Haltwhistle 0950 - 1100 - - 1158 - - 1256 - Brampton 1005 - 1115 - - - - - 1311 - Wetheral 1014 - 1124 - - - - - 1320 - Carlisle a 1024 - 1134 - - 1232 - - 1330 - Middlesbrough d - 1131 - - 1230 - - 1331 - - Hartlepool d - 1201 - - 1300 - - 1401 - - Horden d - 1212 - - 1311 - - 1412 - - Sunderland d - 1230 - - 1329 - - 1430 - - Newcastle a - 1250 - - 1349 - - 1450 - - d 1235 1255 1315 1333 1355 1415 1428 1455 1515 1535 Dunston - - 1321 - - 1420 - - 1521 - MetroCentre a 1243 1302 1324 1341 1402 1424 1436 1502 1524 1543 d - 1303 - - 1403 - - 1503 - - Blaydon - - - - 1407 - - - - - Wylam - 1311 - - 1413 - - 1511 - - Prudhoe - 1315 - - 1418 - - 1515 - - Stocksfield - 1320 - - 1422 - - 1520 - - Riding Mill -

AGENDA 5, Enc Ii) PRUDHOE TOWN COUNCIL DRAFT Minutes of Ordinary Meeting, with Budget, Held in the Spetchells Centre at 6:00Pm, 25Th January 2017

AGENDA 5, Enc ii) PRUDHOE TOWN COUNCIL DRAFT Minutes of Ordinary Meeting, with Budget, held in The Spetchells Centre at 6:00pm, 25th January 2017 PRESENT Cllr Mrs J McGee (Chair), Cllr G Simpson, Cllr B Futers, Cllr A Gill, Cllr G McCreedy, Cllr A Piper, Cllr Ms J Rose, Cllr A Reid, Cllr Mrs E Burt, Cllr Mrs C Cuthbert, Cllr D Couchman, Cllr N McGee, Cllr G Price, County Cllr Mrs A Dale 1617/136 Apologies for Absence Cllr E Dobson 1617/137 Declarations of Interest Cllr A Reid – member of West Area Planning Committee so will not take part in any discussion relating to planning applications. 1617/138 Youth Service Provision in Prudhoe John Smith (Northumberland County Council, Youth Service Manager) and Sharron Pearson (Northumberland County Council, Senior Manager Specialist Services) in attendance Cllr Mrs J McGee read 2 items of correspondence; the first was the initial email from Mike Robbins (NCC Estates) that advised the East Centre would be closed and youth service provision moved to The Fuse; the second and most recent email stating that plans had been ‘put on hold’. Cllr Mrs J McGee said that the young people of Prudhoe had been very vocal in their objections and brought this to everyone’s attention and as well as thanking them for attending acknowledged that they deserved a pat on the back. Cllr Mrs McGee restated that the email received from Mike Robbins on 4th January 2017 was the first the Town Council had heard about the plans. County Cllr Mrs Anne Dale advised that she also was not aware of the sale; this was echoed by Cllr Reid and Cllr Mrs Burt. -

FOI 1155-17 Police Stations

Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) Request 835/15 - Police station closures As at 31.12.2005 31.12.2006 31.12.2007 & 2008 As at 31.12.2009 As at 31.12.2010 As at 31.12. 2011 As at 31.12.2012 to 2013 As at 31.12 2014 As at Sept.2015 As at October 2016 As at October 2017 Forecast to 31/3/2018 Status Relocated to (i) Unit 7, Signal House, Waterloo Place. (ii) Sunderland Central Fire Station, Railway Row, Sunderland. 1 Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge Gillbridge (iii) The Old Orphanage, Hendon SOLD 2 Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington Washington 3 Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields Millbank - South Shields 4 Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead Gateshead 5 Wallsend Wallsend Wallsend Wallsend relocated to Middle Engine Lane SOLD 6 Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane Etal Lane 7 Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street Market Street/Pilgrim street Relocated to Forth Banks SOLD 8 Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington Bedlington -

Our Economy 2020 with Insights Into How Our Economy Varies Across Geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020

Our Economy 2020 With insights into how our economy varies across geographies OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 2 3 Contents Welcome and overview Welcome from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, North East LEP 04 Overview from Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East LEP 05 Section 1 Introduction and overall performance of the North East economy 06 Introduction 08 Overall performance of the North East economy 10 Section 2 Update on the Strategic Economic Plan targets 12 Section 3 Strategic Economic Plan programmes of delivery: data and next steps 16 Business growth 18 Innovation 26 Skills, employment, inclusion and progression 32 Transport connectivity 42 Our Economy 2020 Investment and infrastructure 46 Section 4 How our economy varies across geographies 50 Introduction 52 Statistical geographies 52 Where do people in the North East live? 52 Population structure within the North East 54 Characteristics of the North East population 56 Participation in the labour market within the North East 57 Employment within the North East 58 Travel to work patterns within the North East 65 Income within the North East 66 Businesses within the North East 67 International trade by North East-based businesses 68 Economic output within the North East 69 Productivity within the North East 69 OUR ECONOMY 2020 OUR ECONOMY 2020 4 5 Welcome from An overview from Andrew Hodgson, Chair, Victoria Sutherland, Senior Economist, North East Local Enterprise Partnership North East Local Enterprise Partnership I am proud that the North East LEP has a sustained when there is significant debate about levelling I am pleased to be able to share the third annual Our Economy report. -

Northumberland County Council

Northumberland County Council Weekly List of Planning Applications Applications can view the document online at http://publicaccess.northumberland.gov.uk/online-applications If you wish to make any representation concerning an application, you can do so in writing to the above address or alternatively to [email protected]. Any comments should include a contact address. Any observations you do submit will be made available for public inspection when requested in accordance with the Access to Information Act 1985. If you have objected to a householder planning application, in the event of an appeal that proceeds by way of the expedited procedure, any representations that you made about the application will be passed to the Secretary of State as part of the appeal Application No: 19/01367/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 7, 2019 Applicant: Mr Philip Mellen-Steele Agent: 9 Queen Street, Alnwick, Northumberland, NE66 1RD, Proposal: Proposed rear ground floor extension to enlarge kitchen, utility and living-room; front elevation bay window at first floor over existing; widen driveway and canopy over garage door Location: 11 Lesbury Road, Lesbury, Northumberland, NE66 3ND Neighbour Expiry Date: May 7, 2019 Expiry Date: July 1, 2019 Case Officer: Mrs Esther Ross Decision Level: Ward: Alnwick Parish: Lesbury Application No: 19/01466/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Mrs Rachel Towns Agent: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Proposal: Proposed new single storey garage in addition to previously approved scheme. Location: Hilton, New Ridley, Stocksfield, Northumberland, NE43 7RQ, Neighbour Expiry Date: May 8, 2019 Expiry Date: July 2, 2019 Case Officer: Ms Marie Haworth Decision Level: Ward: Stocksfield And Broomhaugh Parish: Stocksfield Application No: 19/00999/FUL Expected Decision: Delegated Decision Date Valid: May 8, 2019 Applicant: Conchie Agent: Half Acres, Catton, Hexham, Northumberland, NE47 9LH, Proposal: 1) Retrospective permission for 14no. -

5352 List of Venues

tradername premisesaddress1 premisesaddress2 premisesaddress3 premisesaddress4 premisesaddressC premisesaddress5Wmhfilm Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Village Hall Gilsland Brampton Cumbria CA8 7BH Films Capheaton Hall Capheaton Hall Capheaton Newcastle upon Tyne NE19 2AB Films Prudhoe Castle Prudhoe Castle Station Road Prudhoe Northumberland NE42 6NA Films Stonehaugh Social Club Stonehaugh Social Club Community Village Hall Kern Green Stonehaugh NE48 3DZ Films Duke Of Wellington Duke Of Wellington Newton Northumberland NE43 7UL Films Alnwick, Westfield Park Community Centre Westfield Park Park Road Longhoughton Northumberland NE66 3JH Films Charlie's Cashmere Golden Square Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland TD15 1BG Films Roseden Restaurant Roseden Farm Wooperton Alnwick NE66 4XU Films Berwick upon Lowick Village Hall Main Street Lowick Tweed TD15 2UA Films Scremerston First School Scremerston First School Cheviot Terrace Scremerston Northumberland TD15 2RB Films Holy Island Village Hall Palace House 11 St Cuthberts Square Holy Island Northumberland TD15 2SW Films Wooler Golf Club Dod Law Doddington Wooler NE71 6AW Films Riverside Club Riverside Caravan Park Brewery Road Wooler NE71 6QG Films Angel Inn Angel Inn 4 High Street Wooler Northumberland NE71 6BY Films Belford Community Club Memorial Hall West Street Belford NE70 7QE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Magdalene Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed TD14 1NE Films Berwick Holiday Centre - Show Bar & Aqua Bar Berwick Holiday Centre Magdalen Fields Berwick-Upon-Tweed Northumberland -

Ad122-2016.Pdf

Connections 10 — Newcastle » Metrocentre » Blaydon » Ryton » Prudhoe » Corbridge » Hexham from Newcastle X85 — Newcastle » Benwell Grove » Denton Burn » Heddon-on-the-Wall » Horsley » Corbridge » Hexham Mondays to Fridays (except Public Holidays) Saturdays Sundays (including Public Holidays) Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Service number 10 10 10 10 10 10 10 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0650 0720 0820 0923 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0700 0730 0830 0925 1025 1125 1325 1425 1525 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0800 0900 0952 1052 1252 1352 1452 Metrocentre 0708 0738 0838 0941 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0716 0746 0846 0943 1043 1143 1343 1443 1543 Metrocentre 0816 0916 1010 1110 1310 1410 1510 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0737 0808 0909 1013 1115 1215 1415 1516 1617 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0741 0811 0911 1012 1115 1215 1415 1515 1615 Prudhoe Front Street, Co-operative 0842 0942 1040 1140 1340 1440 1540 Hexham Bus Station 0809 0840 0941 1045 1147 1247 1447 1548 1649 Hexham Bus Station 0810 0840 0940 1044 1147 1247 1447 1547 1647 Hexham Bus Station 0911 1011 1112 1212 1412 1512 1612 Service number X84 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Service number X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 X85 Sorry, no service on Sundays or Public Holidays for X84 and X85. Newcastle, Eldon Square 0725 0800 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Newcastle, Eldon Square 0910 1010 1110 1210 1410 1510 1610 Hexham Bus Station 0825 0847 0957 1057 1157 1257 1457 1557 1657 Hexham Bus Station 0957 1057