Typeform Dialogues (2Nd Edn) 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sig Process Book

A Æ B C D E F G H I J IJ K L M N O Ø Œ P Þ Q R S T U V W X Ethan Cohen Type & Media 2018–19 SigY Z А Б В Г Ґ Д Е Ж З И К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ч Ц Ш Щ Џ Ь Ъ Ы Љ Њ Ѕ Є Э І Ј Ћ Ю Я Ђ Α Β Γ Δ SIG: A Revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Type & Media 2018–19 ЯREthan Cohen ‡ Submitted as part of Paul van der Laan’s Revival class for the Master of Arts in Type & Media course at Koninklijke Academie von Beeldende Kunsten (Royal Academy of Art, The Hague) INTRODUCTION “I feel such a closeness to William Project Overview Morris that I always have the feeling Sig is a revival of Rudolf Koch’s Wallau Halbfette. My primary source that he cannot be an Englishman, material was the Klingspor Kalender für das Jahr 1933 (Klingspor Calen- dar for the Year 1933), a 17.5 × 9.6 cm book set in various cuts of Wallau. he must be a German.” The Klingspor Kalender was an annual promotional keepsake printed by the Klingspor Type Foundry in Offenbach am Main that featured different Klingspor typefaces every year. This edition has a daily cal- endar set in Magere Wallau (Wallau Light) and an 18-page collection RUDOLF KOCH of fables set in 9 pt Wallau Halbfette (Wallau Semibold) with woodcut illustrations by Willi Harwerth, who worked as a draftsman at the Klingspor Type Foundry. -

A Typeface History

The Evolution of Typefaces 1440 The printing press is invented by Johannes Gutenberg, using Blackletter typefaces. 1470 More readable Roman Type is designed by Nicolas Jenson, combining Italian Humanist lettering with Blackletter. 1501 Aldus Manutius and Francesco Grio create the first italic typeface, which allows printers to fit more text on each page. 1734 William Caslon creates what is now known as “Old Style” type, with more contrast between strokes. 1757 John Baskerville creates Transitional typefaces, with even more contrast than Old Style type. 1780 The first “modern” Roman typefaces—Didot and Bodoni—are created. 1815 The first Egyptian, or Slab Serif, typeface is created by Vincent Figgins. 1816 The first sans-serif typeface is created by William Caslon IV. 1916 Edward Johnston designs the iconic sans-serif typeface used by London’s Underground system. 1920 Frederic Goudy becomes the first full-time type designer, and creates Copperplate Gothic and Goudy Old Style, among others. 1957 Helvetica is created by Max Miedinger. Other minimalist, modern sans-serif typefaces, including Futura, emerge around this time. 1968 The first digital typeface, Digi Grotesk, is designed by Rudolf Hell. 1974 Outline (vector) fonts are developed for digital typefaces, resulting in smaller file sizes and less computer memory usage. Late 1980s TrueType fonts are created, resulting in a single file being used for both computer displays and output devices such as printers. Windows Macintosh 1997 Regular fonts plus variants Regular fonts plus variants Open Type fonts are invented, which allow for cross-platform use on Macs and PCs. Open Type 1997 CSS incorporates the first-ever font styling rules. -

Making Books – and Chili by David Esslemont the 2012 Victor and Carolyn Hammer Book Arts Lecture King Library, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY

Making Books – and Chili by David Esslemont The 2012 Victor and Carolyn Hammer Book Arts Lecture King Library, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY. Wednesday, November 28, 2012 Thank you. Good evening. How are you? What a great place. There is much here that is relevant to what I want to talk about – besides my breakfast and lunch . where we are eating tonight? An extraordinary wealth of human creativity is to be found at the University of Kentucky. In the King Library, the variety of books, the range of subjects is awe-inspiring. But don’t forget what Charles Dickens said: “There are books of which the backs and covers are by far the best parts.” There is a teaching press, with iron and wooden presses. Isn’t it astonishing to think these presses were once used to print books? I make books. I have an interest in books. You have an some sort. I have an interest in food too – everybody has an interest in food.interest in books. Actually, I find everybody has an interest in books of 1 Lindisfarne I have a particular interest in how books are made – in the creative process – and how original works are shaped by a response to many different things: our heritage and traditions, current events, trends, tastes, technology, the global economy and the environment. The Lindisfarne Gospels was made 1300 years ago, [700 AD] on a small island off the coast of Northumberland, in northeast England. In the tenth century someone added an Anglo-Saxon gloss to the Latin text, producing the earliest surviving Old English copies of the Gospels. -

National Diploma in Calligraphy Helpful Hints for FOUNDATION Diploma Module A

National Diploma in Calligraphy Helpful hints for FOUNDATION Diploma Module A THE LETTERFORM ANALYSIS “In A4 format make an analysis of the letter-forms of an historical manuscript which reflects your chosen basic hand. Your analysis should include x-height, letter formation and construction, heights of ascenders and descenders, etc. This can be in the form of notes added to enlarged photocopies of a relevant historical manuscript, together with your own lettering studies” At this first level, you will be working with one basic hand only and its associated capitals. This will be either Foundational (Roundhand) in which case study the Ramsey Psalter, or Formal Italic, where you can study a hand by Arrighi or Francisco Lucas, or other fine Italian scribe. Find enlarged detailed illustrations from ‘Historical Scripts by Stan Knight, or A Book of Scripts, by A Fairbank, or search the internet. Stan Knight’s book is the ‘bible’ because the enlargements are clear and at least 5mm or larger body height – this is the ideal. Show by pencil lines & measurements on the enlargement how you have worked out the pen angle, nib-widths, ascender & descender heights and shape of O, arch formations etc, use a separate sheet to write down this information, perhaps as numbered or bullet points, such as: 1. Pen angle 2. 'x'height 3. 'o'form 4, 5,6 Number of strokes to each letter, their order, direction: - make a general observation, and then refer the reader to the alphabet (s) you will have written (see below), on which you will have added the stroke order and directions to each letter by numbered pencil arrows. -

Pdf Calligraphy – a Sacred Tradition

CALLIGRAPHY – A SACRED TRADITION Ann Hechle, the distinguished calligrapher, talks to Barbara Vellacott about her work and her lifelong quest to understand the underlying unity of the world. Ann Hechle is a major figure in contemporary western calligraphy. Trained in the tradition of Edward Johnston and Irene Wellington, she is best known for her large scale, collage-like pieces which explore particular themes (Aspects of Language) or the deep meaning of texts (from the Bible, “In the beginning”; from the I Ching, Hexagram 22). The breadth of her subject matter reflects a personal journey which has immersed her in the sacred literatures of the world. In this interview, she gives us privileged access to her magnus opus, her ‘Journal’, in which she explores the principles of form and order – the sacred geometry – which are the well-springs of the creative process: the idea that “all things unfold out of, and are found within, unity”. ‘Calligraphy is more than fine writing.’ Within this simple statement lies an understanding of what it means to become a great calligrapher. The words were a teaching principle of one of the most famous modern practitioners of the art, Irene Wellington. She was a student of Edward Johnston, who famously revived the tradition of calligraphy in Britain in the early twentieth century and whose work and writings – most notably through his book Writing, Illuminating and Lettering – influenced a generation of artists and typographers. Ann Hechle was taught by Wellington and, now in her eighties but still actively working and teaching, she takes an honoured place in the tradition which began with these two great figures. -

Ann Hechle: Calligraphy As Experiment, Expression and Vocation by Sophie Heath, 2004

Ann Hechle: Calligraphy as experiment, expression and vocation by Sophie Heath, 2004 Please note that objects with an accession number (see captions) beginning AH are NOT in the CSC collection. All the images in this essay are copyright Ann Hechle/Crafts Study Centre 2004, unless otherwise stated. Contents • Anne Hechle and Calligraphy in the Crafts Study Centre Collection • The art of formal lettering and the questioning of tradition • Calligraphy writ large – handwriting in unusual places • Personal expression and the craft vocation • Deeper meanings or spirituality and transformation in handwork • Lessons for craft? Ann Hechle and calligraphy in the Crafts Study Centre collection Ann Hechle is a major figure in contemporary British calligraphy. The Crafts Study Centre holds significant examples of her work, building on a strong collection of the pioneering calligraphic work of Edward Johnston and Irene Wellington from the early part of the 20th century.1 In fact Ann Hechle was taught by Irene Wellington, who was taught by Edward Johnston, so a direct educational inheritance links these three important practitioners. The contrasts and continuities between Hechle’s craft and that of her predecessors illustrate some of the pressures and convictions of a calligraphic career in the present. The Headley Trust Project run at the Crafts Study Centre (CSC) has brought significant further works by Hechle into the collection. This initiative has been exceptional in also collecting a body of digital images; these document items which relate to and illuminate the gifted work yet which remain in the maker’s possession. Ann Hechle made available especially suites of preparatory works – drafts, sketches, technical trials, and time-sheets recording hours spent on the work (see Fig. -

Zapfcoll Minikatalog.Indd

Largest compilation of typefaces from the designers Gudrun and Hermann Zapf. Most of the fonts include the Euro symbol. Licensed for 5 CPUs. 143 high quality typefaces in PS and/or TT format for Mac and PC. Colombine™ a Alcuin™ a Optima™ a Marconi™ a Zapf Chancery® a Aldus™ a Carmina™ a Palatino™ a Edison™ a Zapf International® a AMS Euler™ a Marcon™ a Medici Script™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf International® a Melior™ a Aldus™ a Melior™ a a Melior™ Noris™ a Optima™ a Vario™ a Aldus™ a Aurelia™ a Zapf International® a Carmina™ a Shakespeare™ a Palatino™ a Aurelia™ a Melior™ a Zapf book® a Kompakt™ a Alcuin™ a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Vario™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® a Optima™ a AMS Euler™ a Colombine™ a Alcuin™ a Optima™ a Marconi™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf Chancery® Aldus™ a Carmina™ a Palatino™ a Edison™ a Zapf international® a AMS Euler™ a Marconi™ a Medici Script™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf international® a Aldus™ a Melior™ a Zapf Chancery® a Kompakt™ a Noris™ a Zapf International® a Car na™ a Zapf book® a Palatino™ a Optima™ Alcuin™ a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Melior™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® a Medici Script™ a Aldus™ a AMS Euler™ a Colombine™ a Vario™ a Alcuin™ a Marconi™ a Marconi™ a Carmina™ a Melior™ a Edison™ a Shakespeare™ a Zapf book® aZapf international® a Optima™ a Zapf International® a Carmina™ a Zapf Chancery® Noris™ a Optima™ a Zapf international® a Carmina™ a Sistina™ a Shakespeare™ a Palatino™ a a Kompakt™ a Aurelia™ a Melior™ a Zapf Renaissance Antiqua® Antiqua® a Optima™ a AMS Euler™ a Introduction Gudrun & Hermann Zapf Collection The Gudrun and Hermann Zapf Collection is a special edition for Macintosh and PC and the largest compilation of typefaces from the designers Gudrun and Hermann Zapf. -

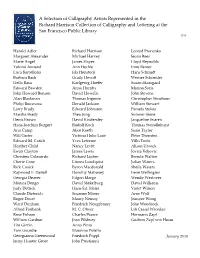

Selection of Calligraphy Artists in the Harrison Collection

A Selection of Calligraphy Artists Represented in the Richard Harrison Collection of Calligraphy and Lettering at the San Francisco Public Library 2018 Harold Adler Richard Harrison Leonid Pronenko Margaret Alexander Michael Harvey Ieuan Rees Marie Angel James Hayes Lloyd Reynolds Yukimi Annand Ann Hechle Imre Reiner Luca Barcellona Ida Henstock Hans Schmidt Barbara Bash Graily Hewitt Werner Schneider Hella Basu Karlgeorg Hoefer Susan Skarsgard Edward Bawden Anna Hornby Marina Soria John Howard Benson David Howells John Stevens Alan Blackman Thomas Ingmire Christopher Stinehour Philip Bouwsma Donald Jackson William Stewart Larry Brady Edward Johnston Pamela Stokes Marsha Brady Theo Jung Sumner Stone Denis Brown David Kindersley Jacqueline Svaren Hans-Joachim Burgert Rudolf Koch Thomas Swindlehurst Ann Camp Alice Koeth Susie Taylor Will Carter Victoria Hoke Lane Peter Thornton Edward M. Catich Yves Leterme Villu Toots Heather Child Nancy Levitt Alison Urwick Ewan Clayton James Lewis Jovica Veljovic Christine Colasurdo Richard Lipton Brenda Walton Cherie Cone Linnea Lundquist Julian Waters Rick Cusick Byron Macdonald Sheila Waters Raymond F. DaBoll Dorothy Mahoney Irene Wellington Georgia Deaver Edgon Margo Wendy Westover Monica Dengo David Mekelburg David Williams Judy Detrick Hans Ed. Meier Violet Wilson Claude Dieterich Suzanne Moore Arne Wolf Roger Druet Maury Nemoy Jeanyee Wong Ward Dunham Friedrich Neugebauer John Woodcock Alfred Fairbank M. C. Oliver Lili Cassel Wronker Rose Folsom Charles Pearce Hermann Zapf William Gardner Joan Pilsbury Gudrun Zapf von Hesse Tim Girvin Anna Pinto Tom Gourdie Massimo Polello Georgianna Greenwood Friedrich Poppl January 2018 Jenny Hunter Groat John Prestianni . -

Pen to Printer.Indd

EDWARD JOHNSTON Extract from Plato’s Symposium. 1934 ARCHETYPE AS LETTERFORM: THE ‘DREAM’ OF EDWARD JOHNSTON Archetype as Letterform: the ‘Dream’ of Edward Johnston BRIAN KEEBLE uring the many hours I have spent in conversa- able scribes to take up calligraphy and lettering, so far as tion with calligraphers and lettercutters over the I know, no one has previously examined this aspect of his D years, I have always been struck by the way in work. If it is time to re-examine the legacy of Johnston, which the practicalities of achieving the ‘perfect’ letter- then this rather more ‘hidden’ aspect ought to be funda- form and its appropriate spacing in a given context is at mental to that re-examination. the root of their preoccupation and effort. No doubt this If calligraphy is to be understood and practised as if it is as it should be. What scribe or lettercutter worth his were more than a skillful game of shape-forming – albeit salt would take up this exacting craft and not be haunted a very sophisticated game – then we might look to the and challenged by the idea of perfection. example of Johnston to learn more of the depths of this But what one rarely comes across, if at all, is a serious ancient, universal skill. Johnston’s was an example that consideration of where the notion of perfection comes prompted one of his pupils to claim of his inspirational from. For it has also been my experience that calligra- teaching that it came as if out of ‘eternity and infinity’. -

Fine Printing & Illustration

Fine Printing & Illustration ¶ Item 68. Jones (David). Coleridge (Samuel Taylor). The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Modern Fine Printing & Illustration Catalogue 1484. Maggs Bros Ltd 48 Bedford Square London 2018 Wood-engraving by Simon Brett of the keystone above the front door at 48 Bedford Square, reproduced here in memory of Cobden-Sanderson’s sacrifice of his type to theThames. Front endpapers: Item 64. Henry (Avril K.). Toys. Back endpapers: Item 3.The endpapers for Donald Glaister's binding of the Ashendene Boccaccio. Maggs Bros Ltd., 48 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DR Contents of Catalogue The William Lang Doves Press collection. 1. Margaret Adams calligraphic album. 2. Art Workers’ Guild. Sketches made on Lithography Night. 1905. 3–7. Ashendene Press. 8. Edward Bawden. How to Make Money. c. 1929. 9. Aubrey Beardsley. The Pierrot of the Minute. 1897 10 & 11. Ian Beck. Fugitive Lyrics. 2013. 12. Edward Burne-Jones. Mezzotint, signed, of Pan and Psyche. 1887. 13. Michael Caine. Lament for Ignacio Sanchez mejias. 1995. 14–16. Corvinus Press. Three rare T.E. Lawrence books. 17–19. Cresset Press. 20. Nancy Cunard, John Banting, John Piper, Ithell Colquhoun and others. Salvo for Russia. 1942. 21–22. Doves Press. 23. Eragny Press. Les Ballades de Villon. 1900. 24–26. Essex House Press. 27. Fleece Press. To the War with Paper & Brush. 2007. 28–30. Robert Gibbings. 31–36. Eric Gill. 37–54. Golden Cockerel Press. 55–61. Gregynog Press. 63. Temporary Culture. Forever Peace: To Stop War. 64. Avril Henry. Original illustrated manuscript of Toys. 65. High House Press. A Marriage Triumph. -

Download a PDF File of the Catalogue Here

METADATA HOW WE RELATE TO IMAGES Lethaby Gallery 10 Jan—3 Feb 2018 An exhibition organised by the International Research Group “Bilderfahrzeuge. Aby Warburg’s Legacy and the Future of Iconology” in collaboration with Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London. Nora Al-Badri and Nikolai Nelles Alexander Burgess Hussein Chalayan Matthew Clarke Joyce Clissold Carole Collet Sarah Craske Matthew Darbyshire John Henry Dearle Violet E. Hawkes Rosemary House Lauren Jetty Edward Johnston Owen Jones Lottin de Laval Richard Long Nicola Lorini Alfred Maudslay Louisa Minkin William Morris Noel Rooke Henrietta Simson Jeremy Wood FOREWORD INTRODUCTION ESSAYS NOTHING ORIGINAL PAPER DECODING NOISE LIST OF IMAGES WORKS EXHIBITED EVENTS CREDITS FOREWORD The exhibition “Metadata: how we relate to images” is just one of many products from a collaboration between the International Research Group “Bilderfahrzeuge. Aby Warburg’s Legacy and the Future of Iconology”, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research and located at the Warburg Institute, and the Art Programme at Central Saint Martins in London. Inspired by specific aspects of the work of the cultural theorist Aby Warburg (1866—1929) the research group investigates, in a number of individual case studies, the significance of the mobility of certain images within cultural history. This exhibition, however, forms a collective product of the group’s work for which the researchers based in London and at other European institutions teamed up with artists from Central Saint Martins. The exhibition engages with the task of combining academic research and artistic practice. The result is a pronounced focus on the actual objects, doing particular justice to Warburg’s concept that gave the research group its name: “Bilderfahrzeuge”, understanding images (Bilder) as automobile “vehicles” (Fahrzeuge), not only loaded with ideas to be transported by them but also driving them with their own dynamic. -

Catalogue 22 Sophie Schneideman Rare Books

Catalogue 22 Sophie Schneideman RaRe BookS We prefer to give customers on our mailing list the opportunity to buy books from catalogues before we put items up for sale on our website. Items in this catalogue will be posted onto www.ssrbooks.com a week or so after the catalogue has been sent out and in many cases there will be additional pho- tographs to view there. If you are interested in buying or selling rare books, need a valuation or just honest advice please contact me at: SCHNEIDEMAN GALLERY Open by appointment 7 days a week or by chance - usually Mon-Fri 10-4. The gallery is open on Saturday 11-5 but if you want to view the books please let me know in advance. 331 Portobello Road, London W10 5SA 020 8354 7365 07909 963836 [email protected] www.ssrbooks.com We aRe pRoUd To Be a MEMBeR oF THE aBa, pBFa & iLaB AND aRe pLEASED To FoLLoW THEIR CODES oF CONDUcT Prices are in sterling and payment to Sophie Schneideman Rare Books by bank transfer, cheque or credit card is due upon receipt. All books are sent on approval and can be returned within 10 days by secure means if they have been wrongly or inadequately described. Postage is charged at cost. EU members, please quote your vat/tva number when ordering. The goods shall legally remain the property of Sophie Schneideman Rare Books until the price has been discharged in full. Cover: Binding for item 7. I · ILLUSTRATED BOOKS ITEMS AESOP 16, 44, 45, 65, 68 BASKIN, Leonard 1 BLAKE, William 2 & 3 BUCKLAND WRIGHT, John 4-6, 89 & 90 GENTLEMAN, David 7 GIBBINGS, Robert 58 GILL, Eric, including