The Artful Dodger: Answering the Wrong Question the Right Way Todd Rogers Michael I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

Depicting and Exploring the Urban Underworld in Oliver Twist (1838), Twist (2003) and Boy Called Twist (2004) Clémence Folléa

Normative Ideology, Transgressive Aesthetics: Depicting and Exploring the Urban Underworld in Oliver Twist (1838), Twist (2003) and Boy Called Twist (2004) Clémence Folléa To cite this version: Clémence Folléa. Normative Ideology, Transgressive Aesthetics: Depicting and Exploring the Urban Underworld in Oliver Twist (1838), Twist (2003) and Boy Called Twist (2004). Cahiers Victoriens et Edouardiens, Montpellier : Centre d’études et de recherches victoriennes et édouardiennes, 2014, Norms and Transgressions in Victorian and Edwardian Times, 79, pp.1-11. 10.4000/cve.1145. hal- 01421062 HAL Id: hal-01421062 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01421062 Submitted on 21 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cahiers victoriens et édouardiens 79 Printemps | 2014 Norms and Transgressions in Victorian and Edwardian Times — Appellations(s)/Naming/Labelling/ Addressing Normative Ideology, Transgressive Aesthetics: Depicting and Exploring the Urban Underworld in Oliver Twist (1838), Twist (2003) and Boy Called Twist (2004) Idéologie normative, -

Oliver Twist Co-Planning: Fagin T14/F16

Oliver Twist Co-planning: Fagin T14/F16 Subject knowledge development Mastery Content for Fagin lesson Review this mastery content with your teachers. Be aware that the traditional and foundation pathways are very different for this lesson. Foundation Traditional • Oliver wakes up and notices Fagin looking at his jewels and Fagin snaps at him in a threatening way. • The meaning of the word villain • Fagin is a corrupt villain • Fagin is selfish. • Fagin teaches Oliver a new game: how to pick pockets. • Oliver doesn’t realise Fagin is a villain • Fagin is a villain because he tricks Oliver into learning how to • Fagin is a corrupt villain steal. • Nancy and Bet arrive and Oliver thinks Nancy is beautiful. Start at the end. Briefly look through the lesson materials for this lesson in your pathway, focusing in particular on the final task before the MCQ: what will be the format of this final task before the MCQ with your class? Get teachers to decide what they want the final task before the MCQ to look like in their classroom. What format will it take? It would be good to split teachers into traditional and foundation pathway teachers at this point. Below is a list of possible options that you could use to steer your teachers: • Students write an analytical paragraph about Fagin as a villain (traditional) • Students write a bullet point list of what evidence suggests Fagin is a villain (traditional) • Students write a paragraph about how Fagin is presented in chapter 10 (foundation). • Students explode a quotation from chapter 10 explaining how Fagin is presented. -

Oliver!? Sharon Jenkins: Working Together

A Study Guide for... BOOK, MUSIC & LYRICS BY LIONEL BART Prepared by Zia Affronti Morter, Molly Greene, and the Education Department Staff. Translation by Carisa Anik Platt Trinity Rep’s Education Programs are supported by: Bank of America Charitable Foundation, The Murray Family Charitable Foundation, The Yawkey Foundation, Otto H. York Foundation, The Amgen Foundation, McAdams Charitable Foundation, Rhode Island State Council on the Arts, The Hearst Foundation, Haffenreffer Family Fund, Phyllis Kimball Johnstone & H. Earl Kimball Foundation, Target FEBRUARY 20 – MARCH 30, 2014 trinity repertory company PROVIDENCE • RHODE ISLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Theater Audience Etiquette 2 Using the Guide in Your Classroom 3 Unit One: Background Information 4-11 A Conversation with the Directors: Richard and Sharon Jenkins 4 A Biography of Charles Dickens 5 Oliver’s London 6 The Plot Synopsis 8 The Characters 9 Important Themes 10 Unit 2: Entering the Text 12-21 Make Your Own Adaptations 12 Social Consciousness & Change 13 Inequitable Distribution of Resources 14 Song Lyrics Exercise 15 Scenes from the Play 17 Further Reading & Watching 21 Bibliography 23 THEATER AUDIENCE ETIQUETTE AND DISCUSSION PLEASE READ CAREFULLY AND GO OVER WITH YOUR CLASSES BEFORE THE SHOW TEACHERS: Speaking to your students about theater etiquette is ESSENTIAL. Students should be aware that this is a live performance and that they should not talk during the show. If you do nothing else to prepare your students to see the play, please take some time to talk to them about theater etiquette in an effort to help the students better appreciate their experience. It will enhance their enjoyment of the show and allow other audience members to enjoy the experience. -

Cultural and Temporal Transfer in the Subtitled Heritage Film Oliver Twist (2005)

Reshaping History: Cultural and Temporal Transfer in the Subtitled Heritage Film Oliver Twist (2005) Lisi Liang Sun Yat-sen University _________________________________________________________ Abstract Citation: Liang, L. (2020). Reshaping The paper will focus on how history is reshaped in a case study: the film History: Cultural and Temporal Transfer in a Heritage Film Oliver Twist (2005). adaptation of Oliver Twist (2005). It is of significance as its Chinese Journal of Audiovisual Translation, 3(1), authorised subtitles mediate nineteenth-century British history for 26–49. a contemporary Chinese audience. But this adaptation creates various Editor(s): J. Pedersen problems of translation as it negotiates the cultural and linguistic Received: October 15, 2018 transfer between early Victorian England and twenty-first-century Accepted: February 20, 2020 Published: October 15, 2020 China. To illustrate the challenge that translators and audiences face, Copyright: ©2020 Liang. This is an open examples drawn from the subtitles are grouped under Eva Wai-Yee access article distributed under the Hung’s (1980) suggested aspects of Dickens’s world: “religious beliefs, terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License. This allows for social conventions, biblical and literary allusions and the dress and unrestricted use, distribution, and hairstyle of the Victorian era”. Moreover, Andrew Higson’s “heritage” reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are theory (1996a), William Morris’s (Bassnett, 2013) views of historical credited. translation and Nathalie Ramière’s (2010) cultural references specific to Audiovisual Translation are adopted to read the Chinese subtitles. They are used to bring back the audiences to an impossible, inaccessible past. The historical features shown in this modern version of a British heritage film make it possible for the subtitles to interact with Chinese culture to transfer meaning via a complex combination of translation strategies. -

English Academic Year Curriculum Overview 2019-20

English Academic Year Curriculum Overview 2019-20 Term Year 7 Autumn 1 Literary Heritage - ‘Oliver Twist’ by Charles Dickens Life in Victorian London What was it like to be poor in Victorian London? The workhouse – Why were people there? What were the conditions like? The Poor Law – why was this so important to Dickens? How did it impact people? The form of the novel: Structure; Vocabulary; Sequence Characters Oliver – how does Dickens create sympathy for Oliver? The Artful Dodger – has he been groomed by Fagin? How would he survive if not by crime? Morality: Who is responsible for the poor? Grammar and Writing - Composing a topic sentence; the subject; subject/verb agreement; the past simple tense Autumn 2 Literary Heritage - ‘Oliver Twist’ by Charles Dickens Victorian Crime How did Oliver become involved in pickpocketing? How can we link crime to poverty? Violent assault – focusing on Bill Sikes. Murder – how does murder make the reader feel about Bill Sikes? Characters: Fagin – his role as a master criminal Bill Sikes – comparing how violent his language and actions are to people and animals Nancy – why does Nancy try and save Oliver even though it puts her in danger? Morality Is crime ever acceptable? What can fear make people do? Spring 1 Literary Heritage – ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ by William Shakespeare Life in Elizabethan England: Context and the role of women The role of theatre as entertainment Life in ancient Athens: The role of power and how people ruled in Ancient Greece How family was different -

Oliver! (1968) AUDIENCE 82 Liked It Average Rating: 3.4/5 User Ratings: 55,441

Oliver! (1968) AUDIENCE 82 liked it Average Rating: 3.4/5 User Ratings: 55,441 Movie Info Inspired by Charles Dickens' novel Oliver Twist, Lionel Bart's 1961 London and Broadway musical hit glossed over some of Dickens' more graphic passages but managed to retain a strong subtext to what was essentially light entertainment. For its first half-hour or so, Carol Reed's Oscar-winning 1968 film version does a masterful job of telling its story almost exclusively through song and dance. Once nine- year-old orphan Oliver Twist (Mark Lester) falls in with such underworld types as pickpocket Fagin (Ron Moody) and murderous thief Bill Sykes (Oliver Reed), it becomes necessary to inject more and more dialogue, and the film loses some of its momentum. But not to worry; despite such brutal moments as Sikes' murder of Nancy (Shani Wallis), the film gets back on the right musical track, thanks in great part to Theatrical release poster by Howard Terpning (Wikipedia) Onna White's exuberant choreography and the faultless performances by Moody and by Jack Wild as the Artful Dodger. The supporting cast TOMATOMETER includes Harry Secombe as the self-righteous All Critics Mr. Bumble and Joseph O'Conor as Mr. Brownlow, the man who (through a series of typically Dickensian coincidences) rescues Oliver from the streets. Oliver! won six Oscars, 85 including Best Picture, Best Director, and a Average Rating: 7.7/10 Reviews special award to choreographer Onna White. ~ Counted: 26 Fresh: 22 | Rotten: 4 Hal Erickson, Rovi Top Critics G, 2 hr. 33 min. Drama, Kids & Family, Musical & Performing Arts, Classics, Comedy 60 Directed By: Carol Reed Written By: Vernon Harris Average Rating: 6/10 Critic Reviews: 5 Fresh: 3 | Rotten: 2 In Theaters: Dec 11, 1968 Wide On DVD: Aug 11, 1998 It has aged somewhat awkwardly, but the Sony Pictures Home Entertainment performances are inspired, the songs are [www.rottentomatoes.com] memorable, and the film is undeniably influential. -

Oliver! Souvenir Brochure

Fa{/i/l Ron Moody Producer John Woolf Vancy hani Wallis Director. ..... ..... .. .............. .. .. 'arol Re d llill ; ·ik,'s " " 00iv r Heed Book, Music and Lyrics by Lion IBart Mr. Bumb! Harry Seeombe L creeuplau .. ..... ... .... ...... • . ... V rnonHarris CllOrengruphy and Musical S equ ences Uli» r Mark Lest '1' Staaed hy Onna White Tlu Artful DwlYe1· Jack WiI,I Music Sup raised. U/7T.lllY clami . The Mayistmtl' HUJ);h Griffit h conducted hy John Green Mr. LJn,1I71l1llJ' • • . • . • . • • • ••• . •• • •• . • . • • •Ioseph O' onor Production Desitmer ~ .•John Box lvII'S. SOIl, ,.rb"·I7"Y Hylda Baker Directur ojPhotofl1Ylphy Oswald MOITis. B.S.C. Mr. SOIl'I. rh errt] . .. .. .••• .... Leonard Rossit I' Film Editor Ralph Kemplen lJat. •'h eila White A ssoclat «: Music Sup ruisor Eric Rozors Wido 11, orneu .... .. .. .... .. .... .... • . Peggy Mount Pruduction Sup roisor Deni s Johnson Ail.'. IJ du -in. .• ... ... Megs Jenkins .4rt Director Terene Marsh Jessop lames Ilayte r Costuuu: Desiuner Phyllis Dalton : oa]: Cla!/pnle Kc nneth ranham Associat« Chorcognlph I' . • ••• .• .• •• • • ••• ••• • Tom Panko Dr. Grimu-iq " " Wensley Pithey Orclusstrution and Chora! Armllll mcnts John Green Charli lJat e.~ . .. .. ... .. .. .. ....... liv > Moss Additional Orchestration Eric Rogers Oth er Fuy i/l);Boys Hol irt Rartl 'Lt hOl'coyraphic IHu .~ic Lauout» Ray IIolder .Jefr handl er MlIsic Editor Kenn th Runyon Chris Duff A ssociat e Music Editor Rober t Hathaway MII.~ie i r i ~re l Gric • Coordinator Dusty Bu.k Ronni J ohnson Assistant Ch'Jrcor/lllph crs Larry Oaks • igel Kingsley G ~ rge Baron Robcrt Langl 'y AssistantDirector ....... ...... ... .. olin Brewer Peter Lock U1I it Production Manaoer Denis Johnson •.Jr. -

Answer Sheet

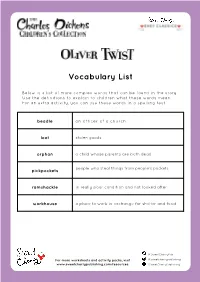

Vocabulary List Below is a list of more complex words that can be found in the story. Use the definitions to explain to children what these words mean. For an extra activity, you can use these words in a spelling test. beadle an officer of a church loot stolen goods orphan a child whose parents are both dead people who steal things from people’s pockets pickpockets ramshackle in really poor condition and not looked after workhouse a place to work in exchange for shelter and food @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Plot Sequencing Answer Sheet 1. Oliver Twist is forced out of the workhouse for asking for more food. The Sowerberrys take him in but treat him horribly. 2. Oliver runs away from the Sowerberrys and spends a week walking to London. 3. Oliver meets the Artful Dodger who introduces him to Fagin’s gang. 4. Oliver is accused of stealing with the gang and the police arrest him. 5. The Brownlows take Oliver in while he recovers from a fever. 6. Bill Sikes finds Oliver and brings him back to the gang. 7. The police come to arrest Fagin. Everyone splits up and runs away. 8. Oliver returns to the Brownlows and learns more about his real family. @SweetCherryPub For more worksheets and activity packs, visit @sweetcherrypublishing www.sweetcherrypublishing.com/resources. /SweetCherryPublishing Reading Comprehension Answer Sheet Q1: What was Oliver’s job at the workhouse? Answer: To unpick old tar-covered strands of ship’s rope so the fibre could be used again. -

Year 7 English Oliver Twist Student Workbook

Student Name: _____________________________________ Year 7 English Oliver Twist Student Workbook A special thanks to Mona Maret, Ark Globe Academy for the adaption and formatting of this material. This workbook has been created to follow the English Mastery 4Hr Traditional Curriculum. This workbook is an optional supplement and should not replace the standard English Mastery resources. It is specifically designed to provide consistency of learning, should any students find their learning interrupted. Due to the nature of the format – some deviations have been made from the EM Lesson ppts. These have been made of necessity and for clarity. Guide for Teachers - Mona Maret, Ark Globe This workbook was designed to function primarily as an independent resource. However, it can be – and is recommended to be – used in the classroom, alongside the lessons, where it can become a valuable tool for quality learning and teaching. It contains all the information provided in the Mastery lessons, the tasks that the students are required to complete and the writing space to complete these tasks. Therefore, it not only has all the information and resources from the lessons, but also the students’ own work. This will give the teacher a clear image of how the students have understood and assimilated the content while also providing the students with an excellent revision tool. However, as this workbook was created first and foremost in the event that students would be forced to work without a teacher, the following elements were heavily factored into its design: 1. Independence – trying to ensure that students could work through the workbook and understand as much of the content as possible on their own. -

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist Charles Dickens Written in 1838, this is the story of a young orphan, Oliver, who runs away to London and meets up with another boy, Jack Dawkins, known as the ARTFUL DODGER. The DODGER introduces Oliver to the sinister Fagin, who runs a Thieves Den, sending out young boys to pick the pockets of the rich. In this scene, Oliver is on his knees cleaning the DODGER's boots for him, while DODGER explains the advantages of joining Fagin s gang. Although the DODGER is young and only four foot six tall, he has all the airs and manners of a man about town. DODGER (Sighs and resumes his pipe) I suppose you don't even know what a prig is? ... I am. I'd scorn to be anything else. So's Charley. So's Fagin. So's Sikes. So's Nancy. So's Bet. So we all are, down to the dog. And he's the downiest one of the lot! He wouldn't so much as bark in a witness-box for fear of committing himself; no, not if you tied him up in one, and left him there without wittles for a fortnight. He's a rum dog. Don't he look fierce at any strange cove that laughs or sings when he's in company! Won't he growl at all, when he hears a fiddle playing! And don't he hate other dogs as ain't of his breed! - Oh no! He's an out-and-out Christian . Why don't you put yourself under Fagin, Oliver? And make a fortun' out of hand? And so be able to retire on your property, and do the gen-teel; as I mean to, in the very next leap-year but four that ever comes, and the forty-second Tuesday in Trinity-week .. -

The Criminal Type of Oliver Twist

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English Summer 8-2013 'This World of Sorrow and Trouble': The Criminal Type of Oliver Twist Megan N. Samples Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Recommended Citation Samples, Megan N., "'This World of Sorrow and Trouble': The Criminal Type of Oliver Twist." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/156 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "THIS WORLD OF SORROW AND TROUBLE": THE CRIMINAL TYPE OF OLIVER TWIST by MEGAN SAMPLES Under the Direction of Dr. Paul Schmidt ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the criminals of Charles Dickens' Oliver Twist as a criminal type: im- poverished, unattractive people who lack family roots. It establishes connections between the criminal characters themselves as well as the real-world conditions which inspired their stereo- types. The conditions of poverty and a lack of family being tied to criminality is founded in real- ity, while the tendency for criminals to be unattractive is based on social bias and prejudice. It also identifies conflicting ideologies in the prevailing Victorian mindset that begins to emerge as a result of research