Procedure for Measurement of Blood Pressure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Morphology of Common Interosseous Artery and Its Clinical

Scholars Journal of Applied Medical Sciences (SJAMS) ISSN 2320-6691 (Online) Sch. J. App. Med. Sci., 2015; 3(3B):1126-1131 ISSN 2347-954X (Print) ©Scholars Academic and Scientific Publisher (An International Publisher for Academic and Scientific Resources) www.saspublisher.com Research Article The Morphology of Common Interosseous Artery and its Clinical Significance Waseem Al Talalwah1*, Dereje Getachew2 and Roger Soames3 1King Abdullah International Medical Research Center / King Saud bin Abdulaziz University for Health Sciences, College of Medicine, Department of Basic Medical Sciences Hospital – NGHA, Riyadh, P.O. Box 3660, Riyadh 2Anatomy Department, College of Medicine and Health sciences, Hawassa University, Awassa, 1560 3Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification, College of Art, Science and Engineering, University of Dundee Dundee, DD1 5EH, UK *Corresponding author Dr. Waseem Al-Talalwah Abstract: The common interosseous artery is main branch the ulnar artery which divides into anterior and posterior interosseous branches. The current study investigates common interosseous artery and its branch to provide detailed information regarding the morphology which would be of use to clinicians, orthopaedic surgeons, plastic surgeons and anatomists. Routine dissections of the right and left upper limb of 34 adult cadavers (20 male and 14 female: mean age 78.9 year) were undertaken. The common interosseous artery presents in 67.6% whereas it is congenital absence in 32.4%. The origin distance of bifurcation of common interosseous from the ulnar artery origin is between 33.11 and 33.45 mm. The anterior and posterior interosseous arteries present in 98.5% and 92.9% whereas they are congenital absence in 1.5% and 7.1% respectively in total cases. -

Additional Branch of Brachial Artery Terminating in Superficial Palmar Arch

International Journal of Advances in Science Engineering and Technology, ISSN(p): 2321 –8991, ISSN(e): 2321 –9009 Vol-6, Iss-1, Spl. Issue-2 Mar.-2018, http://iraj.in ADDITIONAL BRANCH OF BRACHIAL ARTERY TERMINATING IN SUPERFICIAL PALMAR ARCH 1BILLAKANTI PRAKASH BABU, 2HUBAN THOMAS 1Associate Professor, Kasturba Medical College/Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Anatomy Department, Kasturba Medical College,Manipal,KARNATAKA-INDIA,576104 2Senior Lecturer, Kasturba Medical College/Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Anatomy Department, Kasturba Medical College,Manipal,KARNATAKA-INDIA,576104 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Abstract - Superficial palmar arch is an arterial arcade in the palm of the hand formed by superficial branch of ulnar artery and can be completed on lateral side by superficial palmar branch of radial artery or any one of these arteries viz. princeps pollicis artery, radialis indicis artery or the median artery. The arch develops as a terminal plexus of axis artery of upper limb which is later joined by median, ulnar and radial arteries as these arteries develop. The present study was conducted in the Department of Anatomy, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal Academy of Higher Education, Manipal, India on 60 formalin fixed adult human cadaver hands. Out of 60 (30 on right and 30 on left side) in one specimen a unique variation was encountered in the arteries taking part in the formation of superficial palmar arch on the right side. Superficial palmar arch formation was normal and in addition an additional branch arose from the medial side of the brachial artery just below the middle of the arm. -

General Physical Examination Skills for Ahps

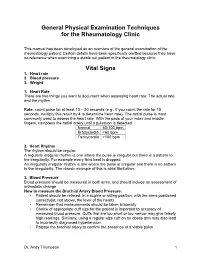

General Physical Examination Techniques for the Rheumatology Clinic This manual has been developed as an overview of the general examination of the rheumatology patient. Certain details have been specifically omitted because they have no relevance when examining a stable out patient in the rheumatology clinic. Vital Signs 1. Heart rate 2. Blood pressure 3. Weight 1. Heart Rate There are two things you want to document when assessing heart rate: The actual rate and the rhythm. Rate: count pulse for at least 15 – 30 seconds (e.g., if you count the rate for 15 seconds, multiply this result by 4 to determine heart rate). The radial pulse is most commonly used to assess the heart rate. With the pads of your index and middle fingers, compress the radial artery until a pulsation is detected. Normal 60-100 bpm Bradycardia <60 bpm Tachycardia >100 bpm 2. Heart Rhythm The rhythm should be regular. A regularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular but there is a pattern to the irregularity. For example every third beat is dropped. An irregularly irregular rhythm is one where the pulse is irregular and there is no pattern to the irregularity. The classic example of this is atrial fibrillation. 3. Blood Pressure Blood pressure should be measured in both arms, and should include an assessment of orthostatic change How to measure the Brachial Artery Blood Pressure: • Patient should be relaxed, in a supine or sitting position, with the arms positioned correctly(at, not above, the level of the heart) • Remember that measurements should be taken bilaterally • Choice of appropriate cuff size for the patient is important to accuracy of measured blood pressure. -

Essentials of Bedside Cardiology CONTEMPORARY CARDIOLOGY

Essentials of Bedside Cardiology CONTEMPORARY CARDIOLOGY CHRISTOPHER P. CANNON, MD SERIES EDITOR Aging, Heart Disease and Its Management: Facts and Controversies, edited by Niloo M. Edwards, MD, Mathew S. Maurer, MD, and Rachel B. Wellner, MD, 2003 Peripheral Arterial Disease: Diagnosis and Treatment, edited by Jay D. Coffman, MD, and Robert T. Eberhardt, MD, 2003 Essentials ofBedside Cardiology: With a Complete Course in Heart Sounds and Munnurs on CD, Second Edition, by Jules Constant, MD, 2003 Primary Angioplasty in Acute Myocardial Infarction, edited by James E. Tcheng, MD,2002 Cardiogenic Shock: Diagnosis and Treatment, edited by David Hasdai, MD, Peter B. Berger, MD, Alexander Battler, MD, and David R. Holmes, Jr., MD, 2002 Management of Cardiac Arrhythmias, edited by Leonard I. Ganz, MD, 2002 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease, edited by Michael T. Johnstone and Aristidis Veves, MD, DSC, 2001 Blood Pressure Monitoring in Cardiovascular Medicine and Therapeutics, edited by William B. White, MD, 2001 Vascular Disease and Injury: Preclinical Research, edited by Daniell. Simon, MD, and Campbell Rogers, MD 2001 Preventive Cardiology: Strategies for the Prevention and Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease, edited by JoAnne Micale Foody, MD, 2001 Nitric Oxide and the Cardiovascular System, edited by Joseph Loscalzo, MD, phD and Joseph A. Vita, MD, 2000 Annotated Atlas of Electrocardiography: A Guide to Confident Interpretation, by Thomas M. Blake, MD, 1999 Platelet Glycoprotein lIb/IlIa Inhibitors in Cardiovascular Disease, edited by A. Michael Lincoff, MD, and Eric J. Topol, MD, 1999 Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery, edited by Mehmet C. Oz, MD and Daniel J. Goldstein, MD, 1999 Management ofAcute Coronary Syndromes, edited by Christopher P. -

Blood Pressure (BP) Measurements in Adults

Page 5 Blood Pressure (BP) Measurements in Adults Ramesh Khanna, MD Karl D. Nolph, MD Chair in Nephrology Professor of Medicine Director, Division of Nephrology University of Missouri-Columbia Uncontrolled high blood pressure is present in every 3rd person in the American community and is attributed to be a major risk factor for progression of chronic kidney disease, coronary artery disease, and stroke. Therefore, blood pressure recording is the most common measurements at home and by healthcare professionals in all of clinical medicine. It might come as a surprise that majority of recordings are done in a less than ideal circumstances and consequently performed inaccurately. BP measurements using mercury sphygmomanometer by a trained health care professional is the gold standard for clinical assessment of blood pressures. The appearance of the 1st Korotkoff sound signals the systolic blood pressure and the disappearance of the 5th sound denotes the diastolic blood pressure. The hypertension experts believe and have increasing evidence to suggest that this method frequently either over diagnose hypertension or fail to recognize masked hypertension (blood pressure that is normal in the physician’s office setting but high at other times including at home). The four commonly recognized reasons for this are: Avoidable inaccuracies in the methods, The inherent variability of blood pressure; and The tendency for blood pressure to increase in the presence of a health care professional (the so-called white coat effect). Failure to standardize blood pressure measurement dos and don’ts. It is believed and also to some extent evidence based that the health care providers including physicians often do not follow established guidelines for blood pressure measurement. -

Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachial Artery

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Brachial Artery Authors Thomas N. Epperson1; Matthew Varacallo2. Affiliations 1 University of Louisville School of Med. 2 Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Kentucky School of Medicine Last Update: January 4, 2019. Introduction The brachial artery is the extension of the axillary artery starting at the lower margin of the teres major muscle and is the major artery of the upper extremity. The brachial artery courses along the ventral surface of the arm and gives rise to multiple smaller branching arteries before reaching the cubital fossa.[1] These branching arteries include the deep brachial artery, the superior ulnar collateral artery, and the inferior ulnar collateral artery. Once the brachial artery reaches the cubital fossa, it divides into its terminal branches: the radial and ulnar arteries of the forearm. The brachial artery and its branches supply the biceps brachii muscle, triceps brachii muscle, and coracobrachialis muscle. The median nerve, a division of the brachial plexus, initially lies lateral to the brachial artery at its proximal segment. At its distal segment, the median nerve crosses the medial side of the brachial artery and lies in the ventral cubital fossa. Structure and Function The following are the branches of the brachial artery in order of origin, proximal to distal. Profunda Brachii/Deep Brachial Artery The first branch of the brachial artery, this branch of the brachial artery arises below the inferior border of the teres major muscle. -

Blood Pressure Year 1 Year 2 Core Clinical/Year 3+

Blood Pressure Year 1 Year 2 Core Clinical/Year 3+ Do Do • Patient at rest for 5 minutes • Measure postural BP and pulse in patients with a • Arm at heart level history suggestive of volume depletion or • Correct size cuff- bladder encircles 80% of arm syncope • Center of cuff aligns with brachial artery -Measure BP and pulse in supine position • Cuff wrapped snugly on bare arm with lower -Slowly have patient rise and stand (lie them down edge 2-3 cm above antecubital fossa promptly if symptoms of lightheadedness occur) • Palpate radial artery, inflate cuff to 70 mmHg, -Measure BP and pulse after 1 minute of standing then increase in 10 mmHg increments to 30 mmHg above point where radial pulse disappears. Know Deflate slowly until pulse returns; this is the • Normally when a person stands fluid shifts to approximate systolic pressure. lower extremities causing a compensatory rise in • Auscultate the Korotkoff sounds pulse by up to 10 bpm with BP dropping slightly -place bell lightly in antecubital fossa • Positive postural vital signs are defined as -inflate BP to 20-30mmHg above SBP as determined symptoms of lightheadedness and/or a drop in by palpation SBP of 20 mmHg with standing -deflate cuff at rate 2mmHg/second while auscultating • Know variations in BP cuff sizes -first faint tapping (Phase I Korotkoff) = SBP; • A lack of rise in pulse in a patient with an Disappearance of sound (Phase V Korotkoff)=DBP orthostatic drop in pressure is a clue that the Know cause is neurologic or related or related to -Korotkoff sounds are lower pitch, better heard by bell medications (eg. -

Does This Patient Have Aortic Regurgitation?

THE RATIONAL CLINICAL EXAMINATION Does This Patient Have Aortic Regurgitation? Niteesh K. Choudhry, MD Objective To review evidence as to the precision and accuracy of clinical examina- Edward E. Etchells, MD, MSc tion for aortic regurgitation (AR). Methods We conducted a structured MEDLINE search of English-language articles CLINICAL SCENARIO (January 1966-July 1997), manually reviewed all reference lists of potentially relevant You are asked to see a 59-year-old articles, and contacted authors of relevant studies for additional information. Each study woman with liver cirrhosis who will be (n = 16) was independently reviewed by both authors and graded for methodological undergoing sclerotherapy for esopha- quality. geal varices. When she was examined by Results Most studies assessed cardiologists as examiners. Cardiologists’ precision for her primary care physician, she had a detecting diastolic murmurs was moderate using audiotapes (k = 0.51) and was good pulse pressure of 70 mm Hg. The pri- in the clinical setting (simple agreement, 94%). The most useful finding for ruling in mary care physician is concerned about AR is the presence of an early diastolic murmur (positive likelihood ratio [LR], 8.8- the possibility of aortic regurgitation 32.0 [95% confidence interval {CI}, 2.8-32 to 16-63] for detecting mild or greater AR (AR) and asks you whether endocardi- and 4.0-8.3 [95% CI, 2.5-6.9 to 6.2-11] for detecting moderate or greater AR) (2 tis prophylaxis is necessary for sclero- grade A studies). The most useful finding for ruling out AR is the absence of early di- astolic murmur (negative LR, 0.2-0.3 [95% CI, 0.1-0.3 to 0.2-0.4) for mild or greater therapy. -

Research Paper Medical Science Variant Brachial Artery with Incomplete Superficial Palmer Arch - a Case Report

Volume : 2 | Issue : 1 | Jan 2013 • ISSN No 2277 - 8160 Research Paper Medical Science Variant Brachial Artery with Incomplete Superficial Palmer Arch - A Case Report Dr. Sharadkumar Associate Professor, Department of Anatomy, K. J. Somaiya Medical College, So- Pralhad Sawant maiya Ayurvihar, Eastern Express Highway, Sion, Mumbai During routine dissection, of the right upper limb of a 70 years old donated embalmed male cadaver in the ABSTRACT Department of Anatomy, K.J. Somaiya Medical College, Sion, Mumbai, India, we observed a high level trifurcation of the brachial artery into the radial, ulnar and common interosseous arteries. The brachial artery trifurcated above the cubital fossa in the lower part of the arm. The ulnar artery travelled downward superficial to the superficial flexor muscles of the forearm. The common interosseous artery was longer in length. The common interosseous artery divided at unusual site in the cubital fossa into the anterior and posterior interosseous arteries. There were no associated altered anatomy of the nerves observed in the specimen. The variations were unilateral and the left upper limb was normal. The photographs of the high level trifurcation of the brachial artery into radial, ulnar and common interosseous artery were taken for proper documentation. Topographical anatomy of the normal and abnormal variations of the axillary artery are clinically important for surgeons, orthopaedicians operating on the supracondylar fracture of humerus and radiologists performing angiographic studies on the upper limb. KEYWORDS: Brachial Artery, Trifurcation, Radial Artery, Ulnar Artery, Common Interosseous Artery, Surgeons, Orthopaedicians Introduction: The brachial artery ends in the cubital fossa by dividing into the ra- dial and ulnar arteries. -

A Review of Pericardial Diseases: Clinical, ECG and Hemodynamic Features and Management

REVIEW SHAM IK AIKAT, MD SASAN GHAFFARI, MD Department of Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic Department of Cardiology, Cleveland Clinic A review of pericardial diseases: Clinical, ECG and hemodynamic features and management ABSTRACT ECAUSE PERICARDIAL DISEASES are com- mon and often misdiagnosed, physi- Pericardial diseases are common, have multiple causes, and cians need to he familiar with their presenta- are often misdiagnosed. Physicians need to recognize the tions and distinguishing features. characteristic and distinguishing features of the three most This article reviews the clinical features, important pericardial conditions: acute pericarditis, cardiac diagnosis, and management of acute pericardi- tamponade, and constrictive pericarditis. In these tis, cardiac tamponade, and constrictive peri- conditions, proper diagnosis and appropriate management carditis. can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality. • THE PERICARDIUM KEY POINTS The pericardium envelopes the heart, extend- ing on to the adventitia of the great vessels. It Acute pericarditis is an important part of the differential is 1 to 2 mm thick and consists of an outer and diagnosis of chest pain syndromes and needs to be an inner layer. The tough, fibrous outer layer is distinguished from acute myocardial infarction both called the parietal pericardium, and the serous clinically and electrocardiographically. inner layer is called the visceral pericardium. The parietal and visceral pericardium are sep- Suspect pericardial tamponade in any patient with acute arated by fluid: 15 to 50 mL of an ultrafiltrate dyspnea, especially in the presence of a pericardial rub, of plasma that acts as a lubricant.1-2 elevated jugular venous pressure, and hypotension. The pericardium limits excessive cardiac movement and acute cardiac distension. -

Simbaby™ Specs

SimBaby™ Specs Normal & Difficult Airway • Airway opening acquired by head tilt, chin lift and jaw trust • Oropharyngeal and nasopharyngeal airways • Bag-Valve-Mask ventilation • Orotracheal and nasotracheal intubation • Sellick Maneuver • LMA insertion • Endotracheal tube insertion • Fiberoptic intubation • Gastric tube insertion • Variable lung compliance • Variable airway resistance • Tongue edema • Laryngospasm • Pharyngeal swelling • Decreased lung compliance • Right mainstem intubation • Gastric distention Pulmonary System • Spontaneous breathing with variable rate, depth and regularity • Bilateral and unilateral chest rise and fall • CO2 exhalation • Normal and abnormal breath sounds – bilateral • Lung Sounds: Normal, course crackles, fine crackles, stridor, wheezes and rhonchi • Oxygen saturation • See-saw respiration • Retractions • Pneumothorax • Unilateral chest movement • Unilateral breath sounds • Unilateral needle thoracentesis mid-clavicular • Unilateral chest tube insertion Cardiovascular System • Extensive ECG library with rate from 20-360 • CPR compressions generate palpable pulses, blood pressure waveform, and generate artifacts on ECG • Heart Sounds:Normal, systolic murmur, holosystolic murmur, diastolic murmur, continuous murmur and gallop • Blood pressure (BP) measured manually by auscultation of Korotkoff sounds • Pulses: Unilateral radial and brachial pulse and bilateral femoral pulses synchronized with ECG • Pulse strength variable with BP • Display of cardiac rhythms via 3-lead ECG monitoring • 12-lead dynamic -

01 Natsis.P65

Folia Morphol. Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 193–200 Copyright © 2009 Via Medica R E V I E W A R T I C L E ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl Persistent median artery in the carpal tunnel: anatomy, embryology, clinical significance, and review of the literature K. Natsis1, G. Iordache2, I. Gigis1, A. Kyriazidou1, N. Lazaridis1, G. Noussios3, G. Paraskevas1 1Department of Anatomy, Medical School, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece 2University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Craiova, Romania 3Laboratory of Anatomy, Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences (Serres), Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece [Received 5 June 2009; Accepted 16 September 2009] The median artery usually regresses after the eighth week of intrauterine life, but in some cases it persists into adulthood. The persistent median artery (PMA) pas- ses through the carpal tunnel of the wrist, accompanying the median nerve. During anatomical dissection in our department, we found two unilateral cases of PMA originating from the ulnar artery. In both cases the PMA passed through the carpal tunnel, reached the palm, and anastomosed with the ulnar artery, forming a medio-ulnar type of superficial palmar arch. In addition, in both cases we observed a high division of the median nerve before entering the carpal tunnel. Such an artery may result in several complications such as carpal tunnel syndrome, pronator syndrome, or compression of the anterior interosseous nerve. Therefore, the presence of a PMA should be taken into consideration in clinical practice. This study presents two cases of PMA along with an embryological explanation, analysis of its clinical significance, and a review of the literature.